Clinical psychiatric experience demonstrates a wide range of variation in behavioral responses to physiological therapies. Present techniques of evaluating therapies by global improvement scores, imprecise diagnostic classification, and target symptoms abstracted from their context were felt to be methodologically inadequate. Following our experience in describing the behavioral reaction patterns to convulsive (

4) and phenothiazine (

6) therapies, a similar analysis of the data derived from imipramine (Tofrānil) therapy was undertaken. In this report various patterns of behavioral response to imipramine are described; and the relationship to such factors as age, sex, pretreatment behavioral pattern, hospital diagnosis, and hospital discharge evaluation are assessed.

METHOD

Hillside Hospital is a 196-bed, open ward, voluntary psychiatric facility for the treatment of patients with early and acute mental disorders whose stay is independent of their ability to pay. All patients are seen in individual psychotherapy, with the expectation that psychotherapy should be given a trial prior to other measures. Somatic therapies are employed by joint decision of the resident therapist and supervising psychiatrist, with the management of medication restricted to the research staff.

Before starting medication each patient is interviewed by a research psychiatrist. During drug therapy the patient's response is assessed in weekly interviews with both the patient and ward personnel, reviewing changes in mental status and hospital adjustment. In biweekly conferences with the psychiatric resident and his supervisor the patient's progress in psychotherapy, affective and symtomatic state, utilization of hospital facilities, and social and familial relationships are discussed.

When it was evident that the standard diagnostic nomenclature was of little use in categorizing behavioral reactions to drugs, and that psychodynamic formulations lacked predictive clarity, it was decided to derive a descriptive behavioral typology for each agent studied. The detailed longitudinal research records were reviewed and a summary statement concerning the patient's behavioral reaction during treatment was made. The patients were categorized on the basis of changes in symptoms, affect, patterns of communication and participation in psychotherapy and social activity. In each category the drug reaction was the determining feature. While no attention was paid at this point to the patient's pretreatment behavioral patterns, except as relevant to the perceived changes, inspection of these groups showed that not only did the patients share similar behavioral changes with drug therapy, but that they also showed similar behavioral pretreatment characteristics.

For certain patients no discernible change in behavior was observed. It was possible to characterize these subjects by their pretreatment behavioral patterns alone, and these patterns did not occur among those groups showing an imipramine effect.

Treatment was begun orally at 75 mg. daily and usually increased each week in 75 mg. steps, to a modal maximum of 300 mg./day in 80% of the patients.

Between October 1958 and July 1961, 215 patients received imipramine. During the early use of the drug it had not been firmly established that an adequate trial of medication required at least three to four weeks. Therefore, 13 patients who had not responded within two weeks had the medication discontinued. In retrospect, these patients had not received an adequate course of imipramine. Records were incomplete in 3 patients and at the time of writing 19 patients had not yet been discharged. These 35 patients are not included in the data analysis.

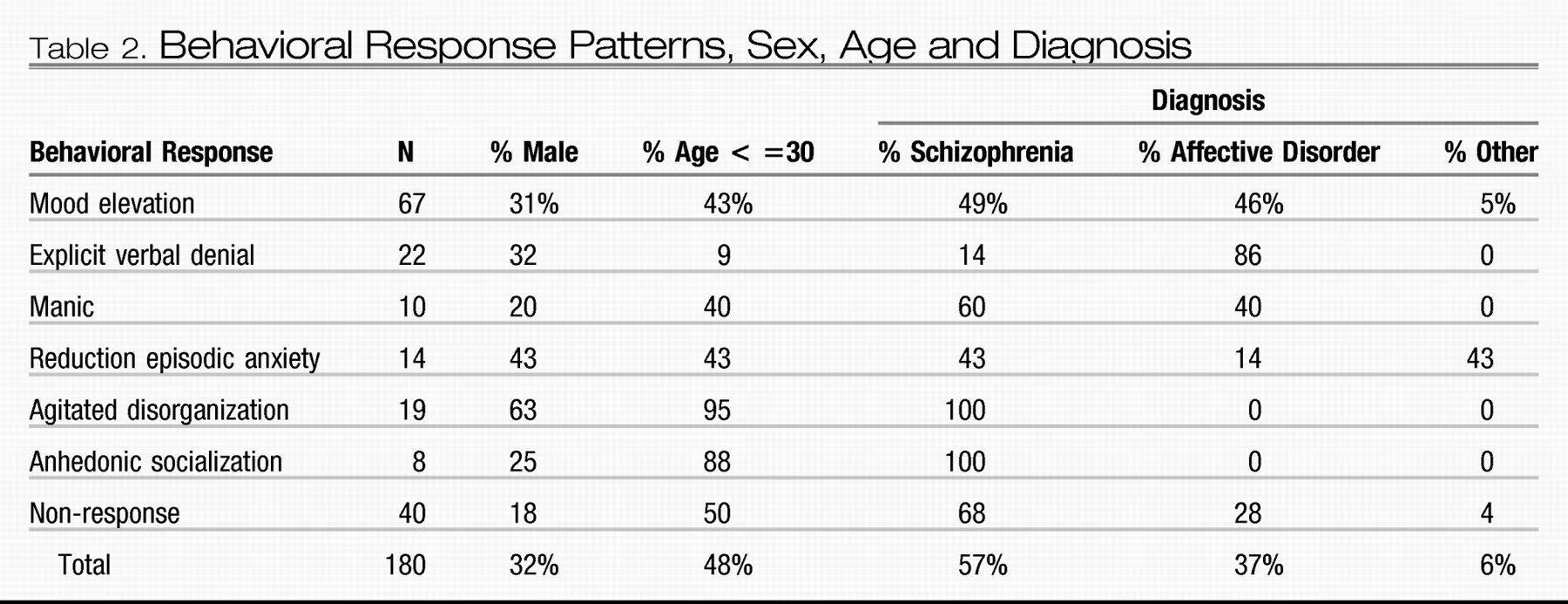

Of the 180 remaining patients, 67 were diagnosed as psychoneurotic depressive reactions, involutional melancholia, manic-depressive reaction, or psychotic depressive reaction. Schizophrenia in various subtypes was diagnosed in 102 patients. Ten patients received diagnoses of psychoneurosis or personality disorder, and one patient was diagnosed as chronic brain syndrome. Since the use of specific affective or schizophrenic subtypes was not discriminating in our analyses, the subgroups were combined.

There were 58 men and 122 women reflecting the sex distribution of the hospital. In this population schizophrenia was diagnosed most commonly in patients below 30 years of age, and affective disorders in patients above 40. However, there was no association of diagnosis or age, with sex.

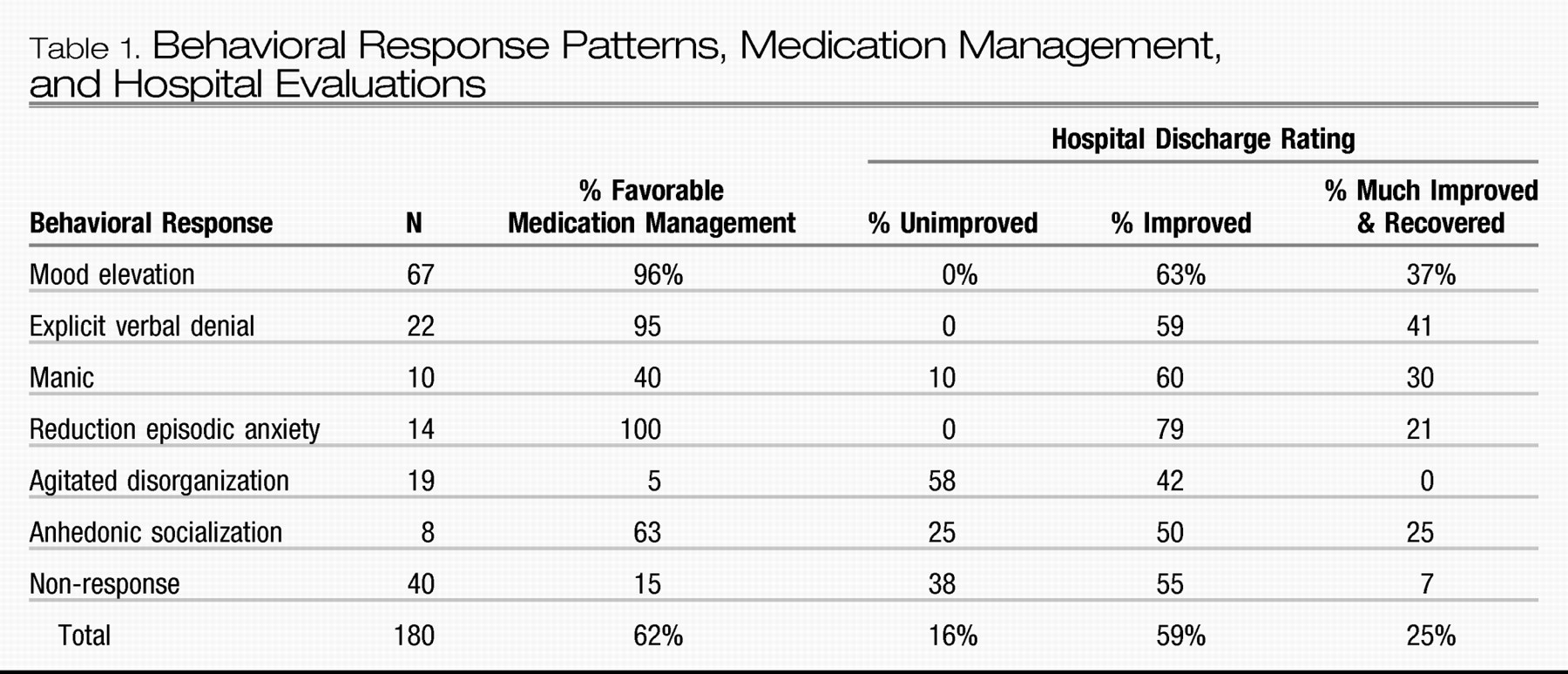

Two methods of evaluating behavioral change were used—a medication management index and a discharge evaluation. The medication management index was based on the various patterns of medication use, reflecting the decision of the therapist as to the value of the medication to the patient—actions proverbially speaking louder than words. Eight patterns were observed, three implying a favorable and five an unfavorable evaluation. Favorable medication management evaluations by the therapist were seen in 115 subjects (68%) and included patients discharged to the community with the recommendation to continue on imipramine therapy (68 patients); patients discharged to the community after imipramine was discontinued with a clinical note that it had accomplished its therapeutic goals and without other somatic therapy prior to discharge (28 patients); and patients discharged to the community to continue imipramine with concurrent phenothiazine medication (19 patients).

Patterns reflecting a therapist's negative evaluation of the behavioral response were seen in 65 patients (32%). These included imipramine discontinued and subsequent treatment with phenothiazines or convulsive therapy prior to discharge (38 patients); imipramine discontinued with the clinical note that it was ineffective and the patients discharged without further somatic treatment (19 patients); and the abrupt ending of imipramine treatment by discharge to another inpatient facility (5 patients), suicide (1 patient), or leaving the hospital against medical advice (2 patients). In this report, the first three patterns of medication use will be referred to as “favorable medication management” and the latter five as “unfavorable medication management.”

In addition, at discharge each patient is given a summary rating as “recovered,” “much improved,” “improved,” or “unimproved” by the staff. This discharge rating is a guide to the effect of hospitalization. It is not the same as the medication management index since other treatment measures may have been interposed after the imipramine treatment. However, this measure will aid in placing the imipramine effects within the context of the general hospital psychiatric treatment. In view of the small number of patients considered “recovered,” this category was combined with “much improved.”

The chi square method of statistical analysis was used and all stated findings are at the .05 level of confidence or better.

CONCLUSIONS

Imipramine appears to be a safe and valuable medication in the treatment of a variety of psychiatric conditions. It produces various behavioral change patterns that are related to both the personality of the patient and the symptom pattern of the illness. While these response patterns cut across the usual nosologic categories, there is a significant statistical relationship to the distinction between schizophrenic and affective disorders. These patterns of behavioral response are highly associated with pretreatment behavioral patterns, and further study may serve to define subgroups whose response to imipramine can be predicted with high probability.

Similar observations are reported by Ayd (

1) in a review of the current status of the “major antidepressants.” Allowing for differences in terminology, his findings closely parallel our own. For example, Ayd notes: Dramatic therapeutic results were seen in those patients often diagnosed anxiety hysteria because their depression was overshadowed by severe anxiety with hysterical features. [They] … had good pre-illness personalities despite an anxious, phobic temperament. In contrast to the classical endogenous depressive, these patients had a normal sleep pattern or insomnia, which readily responded to barbiturate hypnotics, rather than an early morning awakening. Usually they complained of feeling worse as the day wore on. They had little appetite disturbance and no great weight loss. They had many somatic complaints. Seldom were they self-depreciatory. They detested being alone, were voluble, anxious, and tremulous and exhibited psychomotor stimulation instead of inhibition … Tranquilizers invariably made them feel worse, ECT enhanced their anxiety… When treated with an antidepressant they reacted promptly…

The personality organization and behavioral response of these patients are strikingly similar to those described as showing a reduction of episodic anxiety response to imipramine.

This response was seen by Ayd as indicating that in these patients “depression was overshadowed by severe anxiety.” In similar fashion, others have referred to “underlying” or “masked” depressions. The basis for these formulations appears to be the positive behavioral response to “antidepressants,” as the classical signs and symptoms of depression are not clinically manifest. Yet, these patients are refractory to convulsive therapy, which should lead to the inference that they do not have an “underlying” depression.

Such terms represent

ad hoc formulations that obscure common characteristics distinctive in these patients. In an earlier study (

6) we indicated that the behavioral patterns after phenothiazine medication are related to the antecedent behavior, as seen in characteristic adaptive mechanisms, communication patterns, affect, symptoms, psychotherapy participation and social activity. The responses to medication may be used as dissecting tools to uncover various subpopulations and to permit the discovery of specific developmental, physiological, psychological and social similarities within each subpopulation. These common characteristics may also clarify questions of etiology and pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders, and provide rational indications and contraindications for drug therapy. The observations with imipramine reported here suggest that these generalizations may be true for a wide variety of psychotropic agents.