HISTORY

The term “anorexia nervosa” is derived from the Greek for lack of appetite and the Latin for nervous origin. The earliest known medical account of AN was from 1689 by Richard Morton, an English physician and a specialist in tuberculosis, who carefully described the case of an 18-year-old girl who “…fell into a total suppression of her Monthly Courses from a multitude of Cares and Passions of her Mind, but without any Symptom of the Green-Sickness following upon it….I do not remember that I did ever in all my Practice see one, that was conversant with the Living so much wasted with the greatest degree of a Consumption, (like a Skeleton only clad with skin) yet there was no Fever, but on the contrary a coldness of the whole Body; no Cough, or difficulty of Breathing, nor an appearance of any other distemper of the Lungs, or of any other Entrail: No loosness, or any other sign of a Colliquation, or Preternatural expence of the Nutritious Juices” (

1).

In the late 19th century an interest in this condition developed in Europe, after publication of case series of AN by Sir William Gull in England and Charles Lasegue in France, respectively (

2,

3). As Sir Gull noted in some patients, “It seemed hardly possible that a body so wasted could undergo exercise so agreeably.” This illness seems just as perplexing more than a century later.

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of AN is presumed to be complex and influenced by developmental, social, and biological processes (

4). Certainly, cultural attitudes toward standards of physical attractiveness have relevance, but it is unlikely that the preeminent influences in pathogenesis are sociocultural. First, dieting behavior and the drive toward thinness are unusually common in industrialized countries throughout the world, yet AN affects less than 1% of women in the general population. Second, this syndrome has a relatively stereotypic clinical presentation, sex distribution, and age of onset, supporting the plausibility of intrinsic biological vulnerabilities.

Systematic case-control studies show that the relatives of individuals with eating disorders have a 7- to 12-fold increase in the prevalence of AN and BN compared with that for control subjects (

5,

6). These significant familial recurrence risks of AN support impressive evidence that the disorder may be genetically transmitted. The few twin studies of AN suggest a greater resemblance among monozygotic twins relative to dizygotic twins, with 58%–76% of the variance in AN (

7,

8) being accounted for by additive genetic factors. This finding is similar to that seen for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Efforts are underway to identify genes that confer risk for AN.

PHENOMENOLOGY

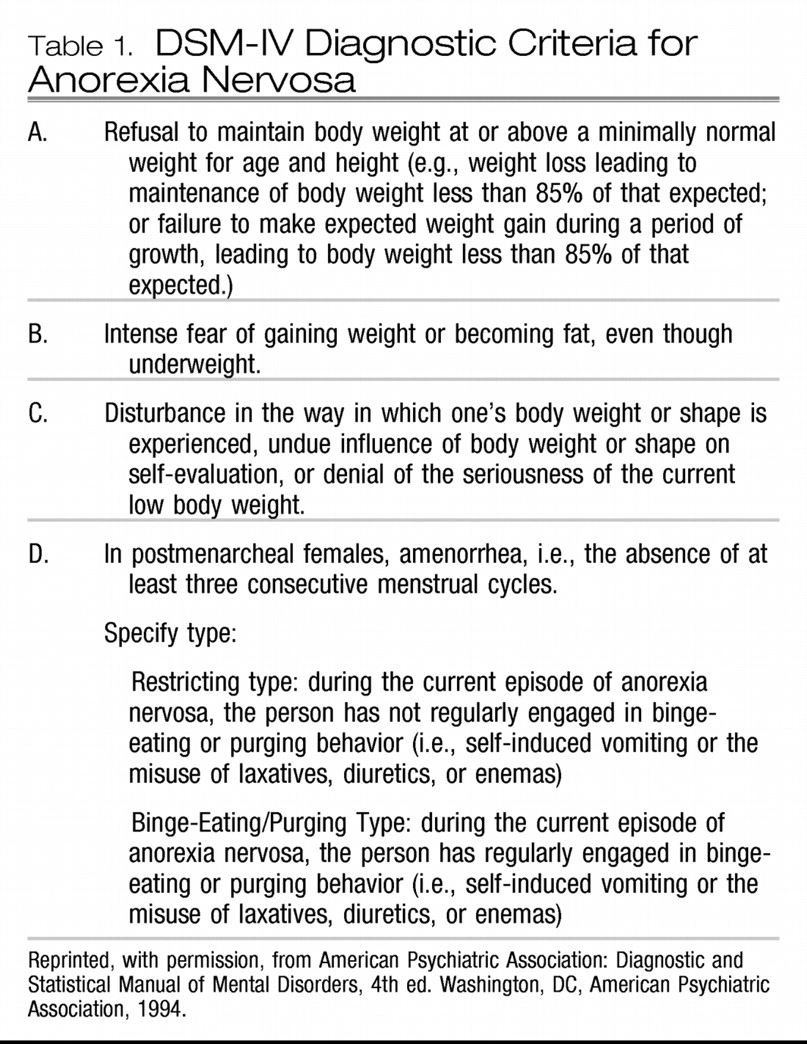

We discuss the clinical features of AN alongside some aspects of BN as these disorders, although separate in DSM-IV-TR, often transform from one to another over the course of the illness (

9,

10). The clinical distinction between AN and BN of most importance is that of emaciation, and although temperamental features of inhibition, restraint, and conformity are especially prominent in AN (

11), there are many shared features and areas of overlap. Individuals with either condition have pathological overconcern with weight and shape, low self-esteem, perfectionism, depression, and anxiety (

12,

13). The diagnostic labels are misleading, as individuals with AN rarely have complete suppression of appetite, but rather exhibit a motivated and, more often than not, ego-syntonic resistance to feeding drives while eventually becoming preoccupied with food and eating rituals to the point of obsession. Similarly, persons with BN, rather than having a primary, pathological drive to overeat, have a seemingly relentless drive to restrain their food intake, an extreme fear of weight gain, and a distorted view of their actual body size and shape. Loss of control of normative feeding patterns usually occurs intermittently and typically only some time after the onset of dieting behavior.

Variations in feeding behavior have been the basis for further subdividing AN into diagnostic subgroups that have been shown to differ in other psychopathological characteristics (

14). In the restricting subtype of AN, lower than normal body weight is sustained by unremitting food avoidance, whereas in the binge-purge subtype, there is comparable weight loss and malnutrition, yet the illness course is punctuated by intermittent episodes of binge eating. Interestingly, individuals with this binge-purge subtype exhibit other dyscontrol phenomena, including histories of self-harm, affective and behavioral disorder, substance abuse, and overt family conflict in comparison with those with the restricting subtype. Regardless of subtype, individuals with AN are characterized by marked perfectionism, harm avoidance, low novelty seeking, conformity, and obsessionality. Most of these clinical features appear in childhood, before the onset of weight loss and tend to persist long after weight recovery. This pattern of onset and persistence of clinical features argues against the notion that they are merely epiphenomena of acute malnutrition or disordered eating behavior (

11,

15,

16).

In the context of conceptualizing the binge-purge subtype of AN, it is useful to consider speculations (

17) on two clinically divergent subgroups of individuals with BN: a so-called “multi-impulsive” type in whom bulimia occurs in conjunction with more pervasive difficulties in behavioral self-regulation and affective instability and a second type whose distinguishing features include self-effacing behaviors, dependence on external rewards, and extreme compliance. Individuals with BN of the multi-impulsive type are far more likely to have histories of substance abuse, and they characteristically display other impulse control problems such as shoplifting and self-injurious behaviors. It has been postulated that multi-impulsive individuals with BN rely on binge eating and purging as a means of regulating intolerable states of tension, anger, and fragmentation; whereas individuals of the second type have binge episodes precipitated through dietary restraint with compensatory behaviors maintained through reduction of guilty feelings associated with fears of weight gain. In this light, it is useful to consider the binge-purge subtype of AN as a multi-impulsive variant and identify distress tolerance as a core goal of treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The most recent National Comorbidity Survey Replication found that the lifetime prevalence in the United States of DSM-IV anorexia nervosa is 0.9% among women and 0.3% among men (

18). The ESEMeD-WMH, a European study that surveyed six countries and only included individuals aged 18 and older, found a lower lifetime prevalence of 0.48%, a number that was 3–8 times higher among women than among men (

19). As anticipated, the European study sets a lower limit for prevalence as it does not factor in data from adolescents.

For most who are affected, AN is a protracted illness; approximately 50%–70% of affected individuals will eventually have relatively complete resolution of the illness, but the time to achieve this state is usually lengthy. Thus, a significant proportion of persons with AN express subthreshold levels of illness that wax and wane in severity long into adulthood, with some individuals having a chronic, wholly unremitting course and with 5%–10% of those affected eventually dying from complications of the disease or from suicide. Furthermore, episodes of binge eating ultimately develop in a significant proportion of people with AN (

20), and some 3%–5% of those starting out with BN will eventually develop AN (

10,

21).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The role of biological factors in the etiology of AN was proposed many decades ago (

4). When malnourished and emaciated, individuals with AN have widespread and severe alterations of brain and peripheral organ function. Such alterations could either be a cause or a consequence of malnutrition and weight loss. To understand the etiology and course of illness of AN, it is useful to divide the neurobiological alterations into two categories. First, there seem to be premorbid, genetically determined trait alterations that contribute to a vulnerability to develop AN. Second, state alterations due to malnutrition might sustain the illness and perhaps accelerate the out-of-control spiral that results in severe emaciation and the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder.

Starvation and emaciation have profound effects on the functioning of the brain and other organ systems. They cause neurochemical disturbances that could exaggerate premorbid traits (

22), adding symptoms that maintain or accelerate the disease process. For example, the structure of the brain is abnormal in the ill state. Ventricles are enlarged and sulci are widened (reviewed in reference

23). Both gray and white matter changes occur with loss of body mass (

24). Although some studies show persistence of changes (

25), other more recent studies show normalization after recovery (

26). In addition, there is a regression to prepubertal gonadal function (

27). The fact that such disturbances tend to normalize after weight restoration suggests that these alterations are a consequence and not a cause of AN.

Recent advances in technologies that permit direct measurements of brain function and relationships to behavior are shedding new light on the pathophysiology of these disorders. It is possible that such trait-related disturbances are related to altered monoamine neuronal modulation that predates the onset of AN and contributes to premorbid temperament and personality symptoms (reviewed in reference

28). Specifically, disturbances in the serotonin system may contribute to a vulnerability for restricted eating, behavioral inhibition, and anxiety, whereas dopamine disturbances may contribute to an altered response to reward. Several factors may act on these vulnerabilities to cause the onset of AN in adolescence. First, puberty-related female gonadal steroids or age-related changes might exacerbate serotonin and dopamine system dysregulation. Second, stress and/or cultural and societal pressures might contribute by increasing anxious and obsessional temperament. Individuals find that restricting food intake is powerfully reinforcing because it provides a temporary respite from dysphoric mood. People with AN enter a vicious cycle, which could account for the chronicity of this disorder, because eating exaggerates and food refusal reduces an anxious mood.

ASSESSMENT

Although many assessment tools are available, there is no gold standard for tracking the severity of illness in eating disorders, as it is not entirely clear that a single psychometric scale accurately and reliably reflects the severity of AN. A particularly important aspect of assessing patients with eating disorders is obtaining information about their baseline and acute medical status. For AN, in addition to tracking weight and distress from food-related preoccupations, it is important to monitor caloric/fluid intake and vital signs and follow abnormal results of laboratory testing. In the binge-purge subtype, it is important to monitor compensatory purging and nonpurging behaviors and correlate reported behaviors with abnormalities in vital signs or laboratory testing. Given the range of medical and psychiatric monitoring necessary, it is essential to include primary care physicians and medical specialists, along with therapists, in treatment planning. Because comorbid substance use can significantly alter the priorities of treatment planning in some patients with the binge-purge subtype, efforts should be made to monitor the contribution of substance use to disordered eating behaviors.

TREATMENT

The treatment of AN has unique challenges not found in other psychiatric disorders. In addition to effectively treating mood and cognitive disturbances, it is critical to provide weight restoration, because malnutrition itself can exacerbate symptoms and can be life threatening.

However, individuals with AN tend to be resistant to engaging in treatment, so that cooperation and motivation are often severely compromised. Moreover, the process of weight gain is relatively slow. Individuals with AN tend to want to eat small quantities of food (a few hundred calories per day). In contrast, weight gain on the order of 1 to 2 pounds per week tends to require 3000 to 4000 calories per day or more. Moreover, patients with AN who sometimes need to gain 30 pounds may require such large daily caloric amounts sustained over many months. Consequently, because of resistance to treatment and the high caloric needs, many individuals with AN are treated in inpatient, residential, or day treatment programs that focus on weight restoration. However, as the etiology of AN is poorly understood, treatment programs tend to use a wide variety of theoretical approaches with few data to support the superiority of any particular approach. Moreover, there is relatively little empirical support for treatment interventions in AN, and advances have been slow (

29). Controlled trials tend to show that compliance with treatment is poor and relapse high (

30). In addition, many individuals have a chronic, relapsing course. However, these facts do not diminish the need for such costly and repeated treatments, because AN has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder, and malnutrition can result in costly and disabling chronic medical problems. Even periodic and partially successful nutritional restoration may be important for preventing morbidity and death. Nonetheless, there is an urgent need for research to develop more cost-effective treatments and to candidly recognize the substantial limitations to conventional approaches.

Treatment approaches can be subdivided based on therapeutic needs into three phases: acute stabilization, weight restoration, and relapse prevention.

Acute stabilization

Acute stabilization is typically required for unstable vital signs, cardiac monitoring during management of severe electrolyte abnormalities, management of refeeding syndrome at very low weights, and rapid weight loss. Although an adjusted ideal body weight less than 75% is usually associated with an increased risk of medical complications, patients without acute medical instability are typically not admitted on presentation to the emergency room. Medical hospitalizations tend to be short and focused on medical stabilization, such as normalization of cardiovascular function but not weight restoration.

Weight restoration

For emaciated patients, it is generally believed that hospitalization in psychiatric units experienced in the treatment of eating disorders applying interdisciplinary approaches, including supportive nursing care and behavioral techniques, is helpful in weight restoration (

31). A recent article, however, called into question the efficacy of specialized treatments for AN (

32). In a randomized trial of 167 adolescents conducted over 2 years, these authors sought to determine whether specialized eating disorders (ED) care, either inpatient or outpatient, offered any advantage over a general outpatient setting. They found that patients in each group improved over 2 years and that specialized units, whether in inpatient or outpatient settings, did not offer any advantage over general outpatient treatment in terms of weight restoration. Importantly, at study completion, only 33% of patients recovered fully, and 27% still met the criteria for AN. Overall, inpatient treatment was predictive of poorer outcomes, and patients for whom treatment in the outpatient setting failed did very poorly in the inpatient setting. This study supports the use of outpatient settings for weight restoration and limiting the use of expensive inpatient hospitalization to acutely stabilize patients. Furthermore, the lack of an advantage for specialized ED units within the centralized UK health care system might result from a high degree of adherence to evidence-based guidelines, even in treatment programs that are not specialized in ED. In a far more heterogeneous US health care milieu, the significant discrepancies in implementing evidence-based practices for AN treatment provide specialized ED centers with an important opportunity to offer and promote treatments supported by controlled trials.

PSYCHOTHERAPY

A wide variety of psychotherapeutic approaches are currently in use to try to help patients and their families cope with AN. However, few are evidence-based and fewer yet show efficacy. Studies have focused mostly on the weight restoration phase, more so in the outpatient than in the inpatient setting and less so during relapse prevention.

Little is known about the relative merit of therapies for weight restoration in the inpatient setting. This situation is particularly problematic because a significant portion of treatment for AN occurs in inpatient settings. The one controlled study that assessed inpatient therapy by randomly assigning adolescents requiring hospitalization to family therapy versus family group psychoeducation showed no difference in weight restoration between the groups (

33). The family therapy encouraged parents to take an “active role” in treatment, whereas psychoeducation involved delivery of information about the illness, such as clinical course and reasons for treatment. At study completion after 4 months of treatment, both groups averaged greater than 90% ideal body weight. Future studies will be needed to assess not only the contribution of different types of therapy to treatment efficacy while controlling for inpatient milieu but also to assess how different inpatient settings can enhance outcomes while controlling for type of therapy.

To assess weight restoration in the outpatient setting, controlled studies have included both individual and family therapies (

34). Individual therapies with proven efficacy in other psychiatric disorders have been adapted for adults with AN. These include cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) (

30,

35–

37), interpersonal therapy (IPT) (

35), supportive psychotherapy (SPT) (

38,

39), psychoanalytic therapy (

40), and psychodynamic (

41) therapy. We first discuss those studies that had a comparison across individual therapies and then the remainder that included group therapies or medications as comparators. In a comparison between individual therapies, 82% of treatment completers in a variant of SPT with clinical management, termed specialist supportive clinical management (SSCM) (

42), were much improved or had minimal symptoms compared with 42% for CBT and 17% for IPT (

35). This result was contrary to the central hypothesis of the study that specialized psychotherapies would result in better outcomes. The flexibility offered by SSCM in combining clinical management and supportive psychotherapy in response to patients' presentations may have contributed to its success in this study. In another study, focal psychoanalytic psychotherapy showed a modest benefit over a low-contact “routine” treatment over 1 year (

40).

Among studies that compared individual with group therapies, CBT was as effective as a behavioral family therapy in outcome variables such as nutritional status and eating behaviors (

37), whereas ego-oriented psychotherapy, a psychodynamic therapy, was less effective in weight gain and resumption of menses compared with behavioral family systems therapy in adolescents at the study completion (

41). In a comparison of individual therapy and medication, CBT was no different than fluoxetine or a CBT/fluoxetine combination in predicting treatment completion (

30). The lone controlled study of individual therapy in adolescents used family therapy as a comparator and found that SPT did better than Maudsley family therapy (discussed below) when the age of onset was older than 18 years, and this effect was sustained at the 5-year follow-up (

38,

39).

Despite the frustration in treating AN, there is some cause for optimism. Family therapy for weight restoration, an approach developed at the Maudsley Hospital in England, has shown significant promise for treating adolescents. In Maudsley therapy, the family is explicitly trained in regaining parental control over the adolescent patient's eating behavior to achieve weight gain (

43). Once weight and eating behavior are normalized, control is gradually returned to the adolescent while moving the focus to rebuilding relationships within the family and pursuing developmental milestones. In a study comparing Maudsley family therapies, in which families were treated either conjointly or in separate sessions, two-thirds of 40 underweight adolescents with AN had weight restoration regardless of therapy arm (

44). Remarkably, 75% of those patients maintained recovery after 5 years (

45). A surprising finding in a recent study was that a shorter 10-session version of Maudsley therapy was as effective as the original 20-session version (

46). However, patients with either a high levels of eating-related obsessionality/compulsiveness or those from a single parent/divorced family did better in the longer form of the treatment compared with the shorter version. The lack of a control or of other types of active treatment groups limits insight into the efficacy of Maudsley therapy. A National Institutes of Health-funded trial of Maudsley therapy versus systemic family therapy, currently underway at multiple sites including ours, is designed to answer such questions.

One of the practical limitations is that few psychiatry clinics provide the intensive outpatient programs necessary to monitor such patients during weight restoration. Upon weight restoration, a relapse prevention plan is needed to monitor and return the patient to treatment as needed.

Relapse prevention

Relapse prevention has been studied in a controlled manner in the original Maudsley family study in adolescents (

43) and in a comparison between CBT and nutritional counseling for adults (

36). In the Maudsley study, family therapy was more effective than individual SPT at the 1-year follow-up of 80 weight-restored adolescents. This benefit did not hold for adolescents ill for more than 3 years or for treatment of adults. In the latter study, although CBT was associated more frequently with “good outcome” (44% versus 7%) compared with nutritional counseling, less than one-fifth of the subjects maintained recovery at 1 year in the CBT treatment arm.

MEDICATIONS

There are currently no FDA-approved medications for any phase of AN treatment. In the acute phase of treatment, as the focus is on inpatient medical stabilization, deferring psychotropics until the weight restoration phase avoids the complicating impact of side effects that emerge early. Even during the weight restoration phase, the role of medications in the treatment of low-weight patients with AN has typically been limited (

47–

49). In contrast to the effectiveness of antidepressant medications in patients with BN, several studies have failed to demonstrate a beneficial effect for the addition of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the inpatient treatment of malnourished patients with AN (

50–

52). Initial interest in the possible benefit of neuroleptics in the treatment of AN was based on clinical observations of weight gain with these medications. However, results from randomized, double-blind controlled trials with pimozide and sulpiride failed to demonstrate accelerated weight gain (

53,

54). Prompted in part by observations of weight gain in other patient groups associated with the use of atypical antipsychotics, a recent controlled trial of olanzapine showed some efficacy in AN (

55). In a placebo-controlled trial in a day hospital setting, 34 patients with AN receiving 2.5–0 mg of olanzapine showed improved weight gain and reduced obsessional symptoms. Previously, promising results had also emerged from case reports and open and small controlled trials of olanzapine (

56–

69), quetiapine (

70–

72), and risperidone (

73,

74). Although the side effect profile from long-term use in this population is largely unknown, clinicians and patients should be aware of the risks of insulin resistance, obesity, and hyperlipidemia from extensive experience in the treatment of psychotic illnesses in other psychiatric populations. It is important to periodically monitor lipid profiles and blood glucose levels to accurately assess the risk-benefit ratio in each patient with AN.

Patients who have achieved weight restoration often have persisting psychological symptomatology accompanied by a significant risk of recurrence of low weight episodes. Medication use, particularly of fluoxetine, has prevented relapse in some but not all individuals studied. A clinically based, prospective longitudinal follow-up study failed to show a significant benefit of fluoxetine treatment compared with historical controls (

75). Subsequently, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in weight-restored patients with restricting-type AN demonstrated that fluoxetine treatment was associated with reduced relapse rate and reductions in depression, anxiety, and obsessions and compulsions (

76). However, a recent study of individuals with both restricting- and binge-eating/purge-type AN failed to demonstrate a difference in time to relapse in weight-restored patients with AN who were receiving CBT and were randomly assigned to adjunctive treatment with fluoxetine or placebo (

77). Although there is no systematic supporting data, it is our clinical impression that after weight restoration, restricting-type AN responds better than binge-eating/purge-type AN to fluoxetine, which is consistent with differences between the groups in serotonin transporter function (

78).