CASE VIGNETTE PART 1

The management of patients who are not able to recover with the initial treatment poses challenges in management, a phenomenon that cuts across virtually all psychiatric disorders.

Kevin W. is a 25-year-old man who initially had experienced disorganized behavior and paranoia at age 19 in the context of daily marijuana use while at college. He had transitioned from sporadically smoking marijuana to daily use when he moved away from home to a large university. He had become distressed by academic difficulties and suspicious feelings about some other students in a particular fraternity. He sought care at the college clinic, and after initially being told by the intake counsellor that he was probably “stressed out” by the demands of college and that he should stop smoking marijuana, he joined a student 12-step program and was able to stop his use of that drug. He performed poorly on his courses that term but did not fail out of the college. Nonetheless, the disorganization continued to adversely affect his academic performance in the next semester, and his situation came to the attention of the dean of students. With reevaluation by a psychiatrist at the college health program at that time, he was given the diagnosis of schizophrenia and was offered treatment with a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) agent at a dose within the therapeutic range. Over the ensuing month, he had some improvement in his paranoia ideation but had persistence of disorganization. Unable to succeed in his college coursework, he elected to take an extended leave of absence and moved back home with his parents.

He refused to see a psychiatrist in his hometown upon his return, but his parents were able to persuade him to be followed by his family doctor, who initially continued his treatment with the same SGA that had been prescribed at the college. After 2 months without change in symptoms, a trial of a second SGA, at a dose at the high end of the therapeutic range for that drug, was initiated. This controlled the paranoid ideation, but the patient was still too disorganized to take classes at a local community college or even to work part time in a local grocery store. Around this time the patient became frustrated with weight gain and sexual dysfunction and stopped his medication.

He rapidly became increasingly paranoid and disorganized and now was experiencing auditory hallucinations as well. The voices directed him to leave home and he wandered away from his parents' residence. He was found 2 weeks later in a park about 100 miles away, when he was picked up by the police in that town for vagrancy; because of his disorganized and confused behavior and his generally disheveled and malnourished state, he was taken to a regional hospital for involuntary hospitalization rather than to a holding cell at the jail.

After being evaluated in the emergency room there, he was admitted to the psychiatric inpatient service, and his parents were contacted for collateral history, because the patient was much too disorganized to be a reliable historian. Because he had failed to have a full response to two different SGAs, he was started on haloperidol, 10 mg at bedtime. His behavior and thought processes appeared to be less catastrophically disorganized within the first few days of hospitalization, and at that time he agreed to sign in for voluntary care. He continued to take his medications and was discharged back to home on hospital day 8. When he was seen by his family doctor 6 weeks later, he had evidence of improvement in paranoia but still had some prominent auditory hallucinations and disorganization.

At this point, he was willing to see an outpatient psychiatrist and was referred to you for evaluation and care. According to the International Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project (IPAP), he has treatment-refractory schizophrenia (

1) with

a.

nonresponse to at least two trials of antipsychotic medications from different classes,

b.

moderate to severe psychopathology, especially positive symptomatology (conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, delusions, or hallucinatory behavior), and

c.

no period of good functioning in the previous 5 years.

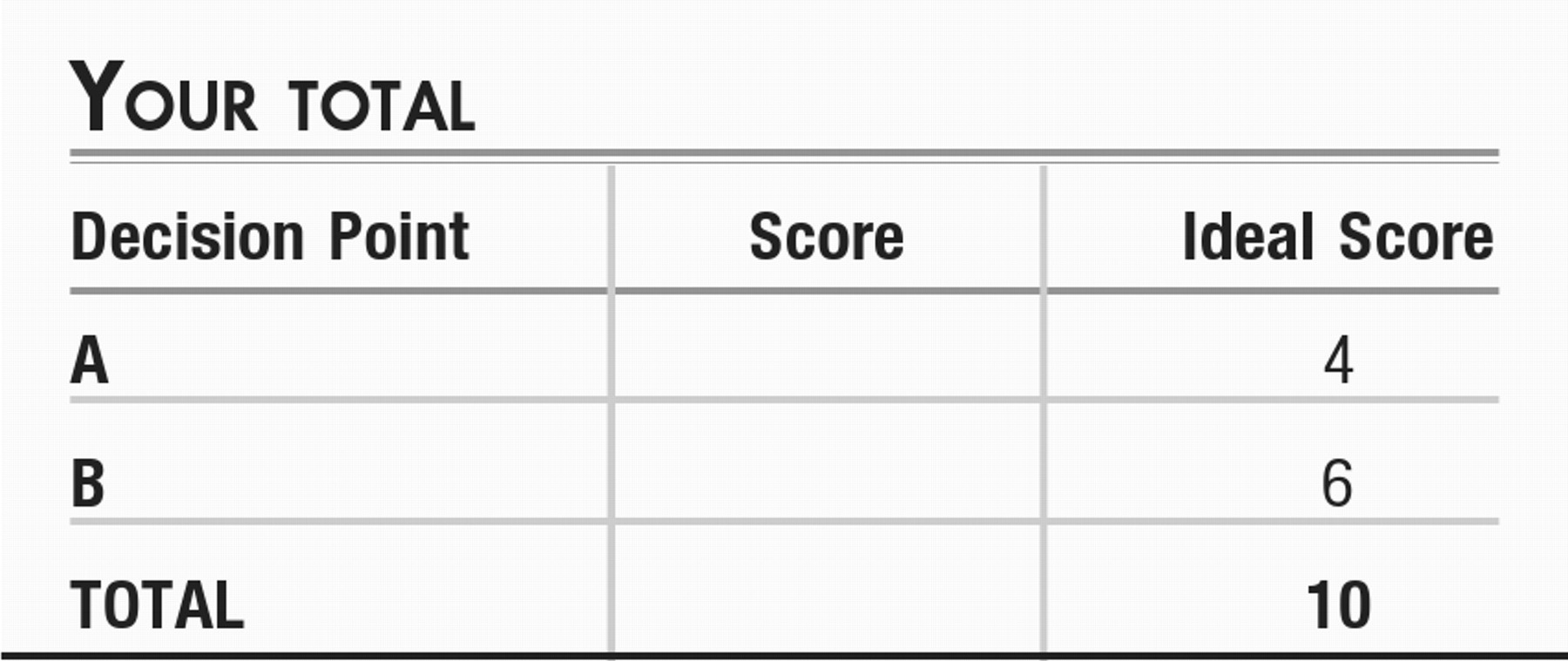

Consideration Point A:

As you review his records and your examination of this patient, some of the options you may consider as a next step in treatment include the following:

| A1._____ | Treatment with a third Second-Generation Antipsychotic agent (SGA). |

| A2._____ | Initiation of social skills training. |

| A3._____ | Treatment with clozapine. |

| A4._____ | Addition of methylphenidate to help him focus his attention. |

CASE VIGNETTE PART 2

Now under your care, the patient agreed to a trial of clozapine. The dose was titrated, and blood monitoring was instituted, and after 3 months of use, he experienced near-complete resolution of disorganization, hallucinations, and paranoia. He reported that, although he was clearly happy at last not to have these symptoms, he was having difficulty in his efforts to date because of the excess salivation and weight gain, side effects which both you and he ascribed to clozapine.

Social skills training was introduced. With this, Kevin was able to start working part-time at a local merchant and to take one class at the local community college. He reported that he had expanded his circle of friends.

After 2 months, his parents reported that he had become increasingly paranoid again. You saw him in your office, and your examination confirmed that he appeared to have had a return of paranoid ideation, with concerns mostly focused on police, the CIA, and other authority or law-enforcement figures.

Consideration Point B:

What source(s) of data would you consider collecting at this point?

| B1._____ | Obtain blood for a serum clozapine level to assess adherence. |

| B2._____ | Obtain Rorschach projective testing to assess level of psychosis. |

| B3._____ | Obtain urine for toxicology assessment. |

CONCLUSIONS

You determined that Kevin's urine showed evidence of marijuana and cocaine use. His blood level of clozapine was found to be low. In discussion with him, you learned that, as he developed a larger circle of friends, he had gravitated to associate with those who also had used marijuana, and now with money from his job and access to drug dealers, he had returned to daily marijuana use. He also had become introduced to cocaine use through his “friends.” With his attention increasingly devoted to substances of abuse, he had neglected to take clozapine as directed. He voiced despair at having relapsed with drugs of abuse and in disappointing his parents and you.

A family meeting was convened, and treatment options were reviewed. The patient and his family agreed with your recommendation for a brief inpatient detox program, to be followed by a dual-diagnosis program at a residential treatment center. He was able to follow through on your plan and while in the residential program was able to incorporate daily exercise into his life to address the weight gain he had associated with medication use. He was able to achieve symptom control with the reintroduction of clozapine.

After 4 months, he was discharged and went to live with his parents who had moved to a new town. In this new environment, he was able to maintain his abstinence, attend classes as a part-time student at a local college, and work part-time in a local business. He was able to use clozapine effectively as a component of his total treatment plan, which also included a 12-step program, a specialized cognitive behavior therapy program (

10), and a clubhouse program (

11).