Findings of the Present Study

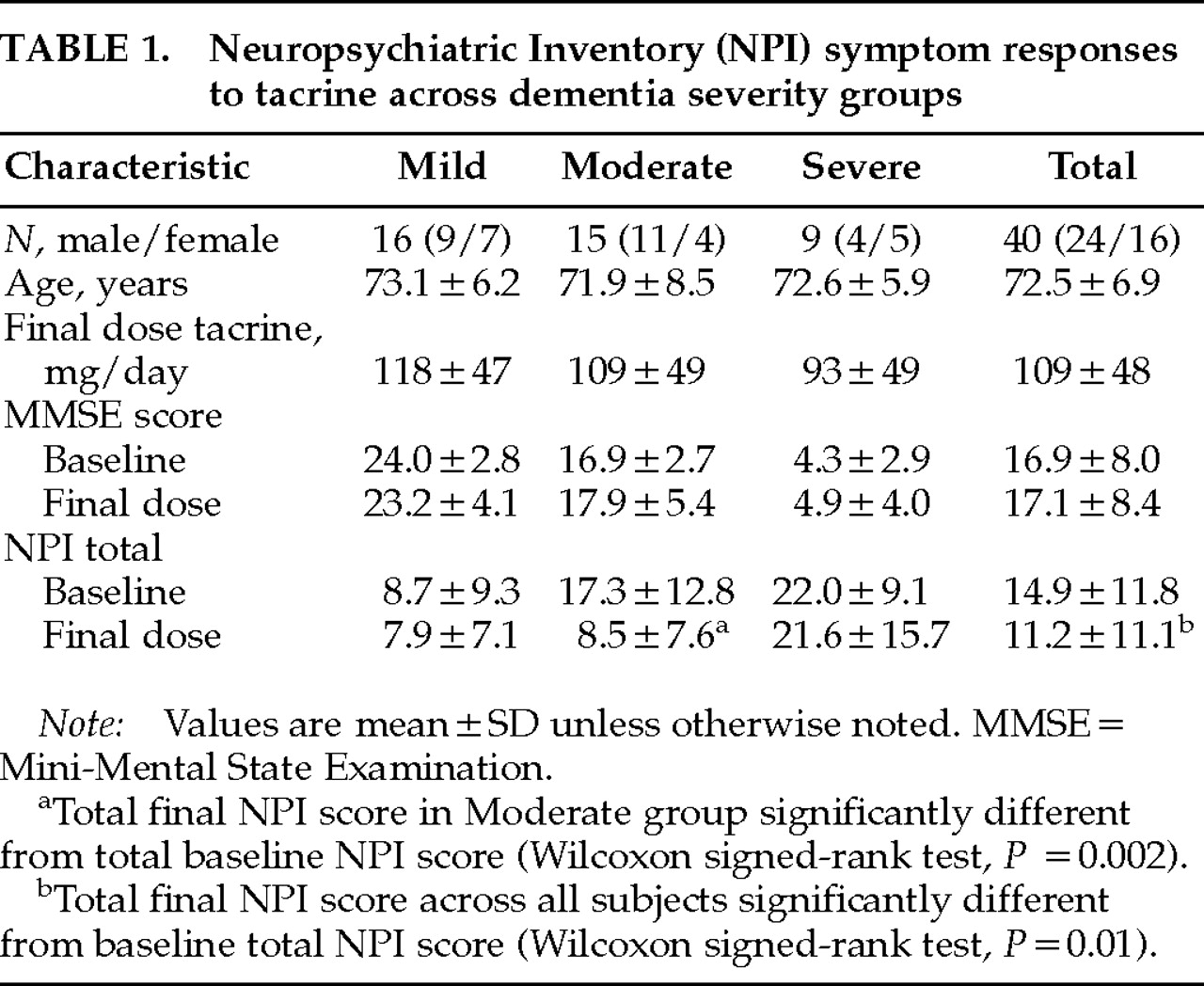

The present study significantly extends our previous report

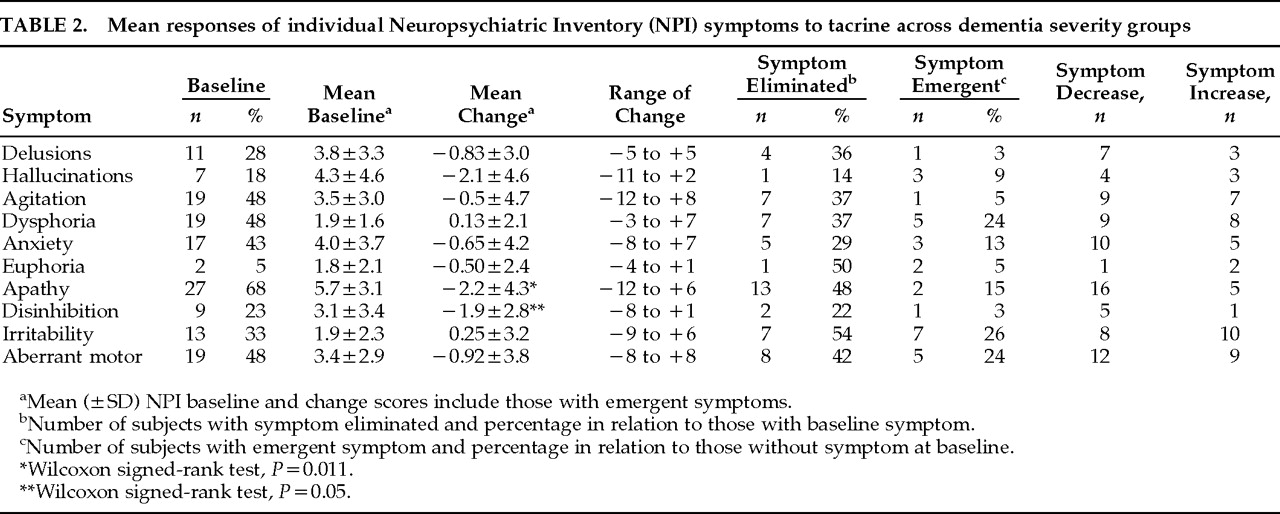

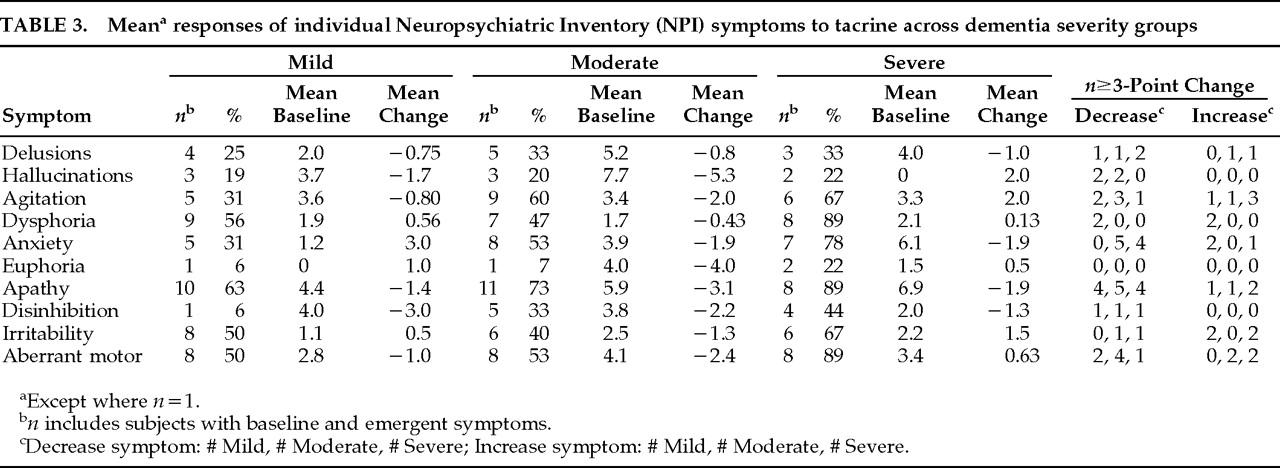

12 by examining differential responses of neuropsychiatric symptoms across different levels of dementia severity and symptom baseline and response interrelationships. Such data have not been reported and provide important insight into the nature and heterogeneity of clinical responses to cholinergic agents in AD. The present study also includes a 30% larger sample size, uses more conservative nonparametric statistical analyses, and takes account of emergent symptoms in change score comparisons (not just the effect of tacrine on baseline symptoms). Two main findings of this extended open-label study of tacrine in AD add further support to previous observations: 1) an overall significant reduction in neuropsychiatric symptoms reported on the NPI in a cross-section of AD patients representing different levels of dementia severity, and 2) a stage-specific (Moderate group) predilection for beneficial neuropsychiatric symptom responses. Previously observed significant or nearly significant reductions in anxiety and aberrant motor behaviors were not confirmed in the present study when emergent symptoms were included in the analysis. Significant reductions in apathetic and disinhibited behaviors were observed across all subjects with these symptoms, and, together with delusions, were the only symptoms to exhibit net decreases at all levels of dementia severity. All other symptoms showed differential stage-specific responses during tacrine treatment.

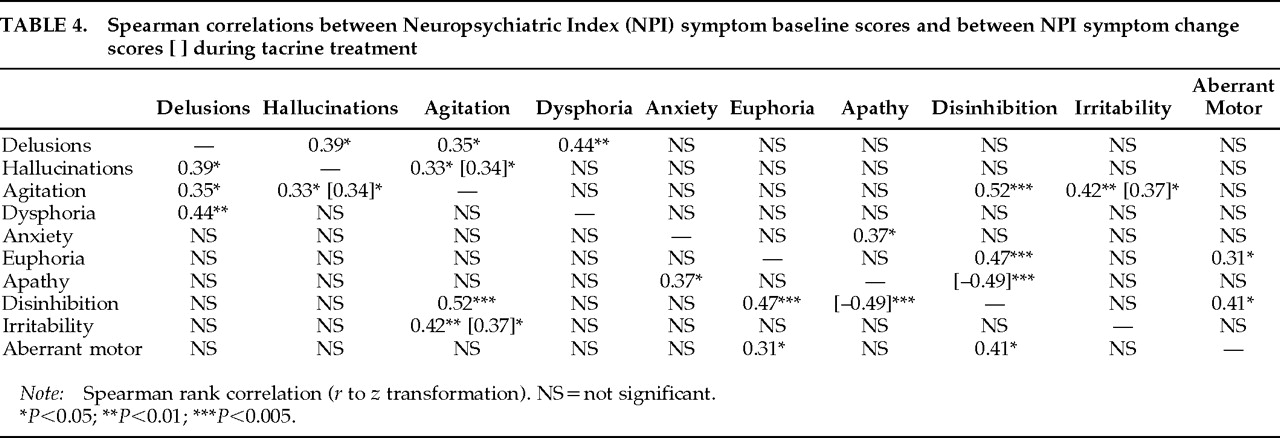

In addition to characterizing the stage-specific nature of individual neuropsychiatric symptom responses to tacrine in AD, this study extends the previous study by exploring relationships between baseline symptom scores and between treatment-based symptom change scores. Baseline agitation scores and agitation change scores during treatment were both correlated with these respective indices of two other symptoms, hallucinations and irritability. However, whereas agitation and hallucinations tended to decrease together in moderately demented subjects, symptoms of agitation and irritability tended to increase together in Mild and Severe subjects. The differential response relationships between agitation and other neuropsychiatric symptoms highlight the variable determinants of agitated behaviors across different stages of AD.

2 The observed inverse relationship between changes in apathetic and disinhibited behaviors may appear somewhat paradoxical in that both symptoms showed net decreases across all subjects; within individual subjects, however, decreases in one of these symptoms were generally much greater than increases in the other. Despite the limitations imposed by an open-label design and relatively small sample size, several tentative conclusions emerge from this extended exploratory investigation.

Neuropsychiatric symptom improvement is most apparent in patients with moderately severe cognitive impairment (MMSE range 11 to 20). The net effect of tacrine on composite NPI scores in moderately demented subjects was to reduce them to a level seen in mildly demented subjects. The pattern of observed responses is not consistent with “regression to the mean,” for this would predict the symptom reduction would be greatest in the most severely demented subjects—that is, in subjects with the lowest MMSE and highest NPI scores. Within the Severe group, subjects with lower MMSE scores generally had less improvement or worsening of NPI-rated symptoms than those with higher MMSE scores, consistent with the expectation that a cholinesterase-inhibitor agent will have less of an effect on more advanced AD cases because of severely diminished acetylcholine production. That patients with moderately severe dementia, and not those receiving the highest doses of tacrine, consistently improved suggests that the observed changes may be attributable to neurobiological differences across different levels of dementia severity and are not dose-dependent or placebo responses.

The observed association between psychotic symptoms (delusions and hallucinations) and agitation in AD is consistent with previous reports.

16–18 However, only changes in hallucinations and agitation, principally reflecting concomitant symptom reductions in moderately demented subjects, were correlated during treatment. Delusional symptoms were significantly associated with depressive symptoms at baseline, showed consistent, if not dramatic, decreases at all dementia severity levels, and were eliminated in one-third (4/12) of subjects with this symptom at baseline. These findings are congruent with previous reports of an increased incidence of mood disturbances in AD patients with delusions

19 and a reduction in delusional symptoms in AD patients treated with the cholinesterase inhibitor physostigmine.

20,21 In contrast, hallucinations were markedly reduced in Moderate subjects but emerged in 2 Severe subjects. Together, these data suggest an overlapping cholinergic-sensitive pathophysiology linking delusions and hallucinations in AD, but the data highlight potential differences in these symptoms with respect to differential response patterns to cholinergic treatment.

Imbalances between cholinergic and monoaminergic transmission have been associated with both delusions and hallucinations, but these psychotic manifestations may differ in their anatomical substrates.

22,23 Delusional symptoms, often paranoid in AD, have been most closely linked to dysfunction in limbic regions of the medial temporal lobe and caudate nucleus.

23 Medial temporal areas typically bear the earliest and greatest pathological burden (including cholinergic deficits) in AD, and significantly reduced choline acetyltransferase activity has been observed in the caudate nuclei of both AD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) patients compared with normal elderly subjects.

24 Cholinergic deficits in neocortical (compared with medial temporal) areas are more severe in DLB than AD patients,

24,25 and these deficits have been correlated with the presence of hallucinations.

22 Acetylcholine has differential effects on thalamic and cortical neurons that combine to enhance cortical sensory signal detection and selection.

26,27 To the extent that hallucinatory experiences may involve aberrant thalamocortical sensory information processing, cholinergic augmentation may ameliorate hallucinations by shifting the relative balance between spurious and actual sensory input. Patients with DLB may particularly benefit from cholinergic therapy because of the severity of neocortical cholinergic deficit and relative absence of AD neuropathology.

28,29Apathetic behaviors were the NPI-rated symptom most consistently responsive to tacrine treatment. Apathy—reflecting lack of spontaneity, reduced motivation, or behavioral disengagement—and disinhibited behaviors—generally representing behavioral excess with respect to social or self-generated activities—have been suggested to constitute the polar dimensions along which personality alterations in AD and other degenerative brain diseases are manifest.

30,31 The significant inverse relationship observed between apathy and disinhibition change scores during treatment provides empirical support for this construct. Together, these findings suggest that tacrine may have a moderating effect on personality alterations in AD along the dimensions of apathy and disinhibition. Apathetic and disinhibited behavioral alterations are associated with dysfunction in separate frontal-subcortical circuits and are putatively linked to lesions of dopaminergic and serotonergic pathways, respectively.

31–34 Cholinergic modulation of these monoamine neurotransmitter systems by tacrine

35 may contribute to the amelioration of personality changes in Alzheimer's disease.

Putative Mechanisms of Cholinergic Responsivity in AD

Individual variations in the topographic distribution, severity, and nature (muscarinic versus nicotinic) of cholinergic denervation in AD may contribute to specific neuropsychiatric manifestations and their relative responsivity to cholinergic augmentation therapy. A dynamic balance between functional (neurochemical) and structural neuropathologic alterations and the relative degree of alteration in other neurotransmitter systems may also influence differential symptom responsivity in relation to disease stage. Alterations in central monoamine metabolism, as well as changes in cholinergic function, have been implicated in the pathophysiology of noncognitive neuropsychiatric symptoms such as apathy, depression, aggression, psychomotor disturbances, and psychosis.

32,33,36–38 Tacrine has also been shown to alter central dopaminergic and serotonergic metabolism.

39 Alhainen and colleagues

40 observed selective increases (toward normal levels) of CSF dopamine and serotonin metabolite levels in AD subjects who showed improved performance on attention and orientation tasks during tacrine treatment. The relative degree to which treatment-based reductions in neuropsychiatric symptoms are attributable to direct cholinergic augmentation, or are indirectly mediated by cholinergic modulation of monoamine transmitters, or reflect a direct influence on noncholinergic neurotransmitter systems is not known.

35,41,42 Dementia severity in AD has been correlated to the degree of cholinergic, but not monoaminergic neurotransmitter deficit.

43 Markers of cholinergic dysfunction thus may provide insight into the differential nature of neuropsychiatric symptom responsivity to cholinergic agents in relation to dementia severity.

Structural pathological changes in AD are typically most concentrated in medial temporal and in temporoparietal neocortical association areas, which generally parallel the topography of cholinergic deficits.

44,45 However, pathological alterations are generally less abundant in frontal neocortical association areas in early to middle stages of AD, whereas the degree of cholinergic dysfunction is almost as severe as in medial temporal and more posterior neocortical areas. A relatively higher degree of cholinergic deficit than of structural pathological alterations in frontal lobe areas—as might be the case in moderately demented AD—may render functional deficits associated with these regions more susceptible to cholinergic therapy. Previous studies have observed that selected attentional and executive functions are the neuropsychological deficits in AD patients that are most responsive to tacrine therapy.

46,47 In addition to these putative frontal lobe–mediated cognitive functions, neuropsychiatric symptoms including apathy, disinhibition, agitation, and psychosis have been associated with functional abnormalities in frontal lobe regions on radionuclide functional imaging studies.

48,49 The observation that AD patients carrying an apolipoprotein E4 (APOE E4) allele are less responsive to cholinesterase-inhibitor therapy

50 may be related to postmortem evidence that choline acetyltransferase, the synthetic enzyme for acetylcholine, is more severely depleted in frontal lobe regions of AD patients with the APOE E4 allele.

51 Together, these observations impute a frontal lobe–associated functional topography of therapeutic response to cholinergic agents in AD.