Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) accounts for about 20% of dementia cases and is characterized by dementia, fluctuating cognition, extrapyramidal signs (EPS), and visual hallucinations.

1 The literature on the clinical features in DLB has focused mainly on the psychiatric and cognitive symptoms, whereas less is known regarding the severity and characteristics of EPS. There is no consensus regarding the proportion of DLB patients with EPS; the reported rates of EPS range from 45%

2 to 100%.

3There are several possible reasons for these reported variations in the prevalence of EPS. First, DLB is a neurodegenerative disease involving both cortical and subcortical brain regions,

1 and variations in the regional distribution of pathology and the corresponding clinical presentations might be expected. Second, most studies have included samples too small to be fully representative of the general DLB population. Given the clinical variation, large samples are needed to establish the frequency of clinical features in DLB. Third, because motor, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms occur, DLB patients are referred to neurological, geriatric, or psychiatric centers. Selection bias may therefore occur. Fourth, the methods of assessing EPS have varied. In some studies, retrospective studies of case notes have been used,

4 and quantitative methods to assess EPS usually were not employed. Finally, there is considerable diagnostic overlap between DLB and PD, and some DLB patients are misdiagnosed as having PD.

5 To compare the clinical features in DLB and PD patients, diagnostic criteria of PD with a high specificity should be used.

PD is the most common neurological basal ganglia disease, with a prevalence of 1% in those over 65 years.

6 Both DLB and PD are part of the spectrum of Lewy body disease, and dementia and hallucinations are common in both. The nosological distinction between PD and DLB is complex and not yet fully resolved. It is suggested that patients presenting with EPS one year before dementia and hallucinations should receive a diagnosis of PD with dementia, although this time frame is somewhat arbitrary.

1 Comparison of the clinical features of PD and DLB would potentially help in the clinical and nosological differentiation between the two diseases.

To overcome some of the limitations of previous investigations, we designed a study to compare the frequency and severity of EPS in two large and representative samples of patients with clinical probable DLB

1 and clinical definite PD.

6 Postmortem confirmation of diagnosis was obtained for 33% of DLB cases. Published diagnostic criteria with high specificity were employed,

1,7 and EPS were evaluated prospectively by using a validated and reliable rating instrument, the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS).

8 A modified version, shown to provide a reliable and generally applicable instrument for the assessment of parkinsonism in DLB patients,

9 was used in this study.

RESULTS

Prevalence of Extrapyramidal Signs in DLB

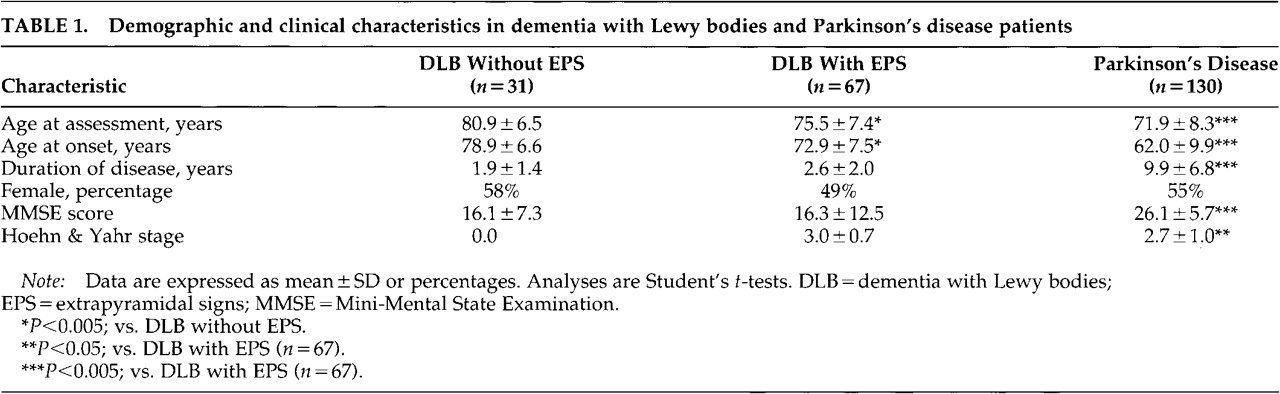

Ninety-eight DLB and 130 definite PD patients were included. Sixty-seven DLB subjects (68%) had a Hoehn and Yahr stage score of 1 or higher, whereas 31 (32%) did not have EPS. Three of those without EPS were being treated with levodopa, indicating previous EPS. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in

Table 1. DLB patients with EPS were younger, had an earlier onset of disease, and showed a nonsignificant trend toward a higher proportion of men than those without EPS (

Table 1). Nine DLB patients without EPS (29%) and 25 with EPS (37%) had autopsy-confirmed DLB, and nigral cell loss was assessed in 23 DLB patients. A significant association between severity of nigral loss and the Hoehn and Yahr stage in this subgroup was found (gamma=0.8,

P<0.001).

Extrapyramidal Signs in DLB and PD

In the subsequent analyses, only the DLB patients with EPS were included. When contrasted with the PD patients, DLB patients with EPS were older, were cognitively more impaired, and had both a later disease onset and a shorter duration of disease (

Table 1). Nine patients had had incomplete UPDRS ratings, and thus 58 DLB patients were included in the analyses of EPS.

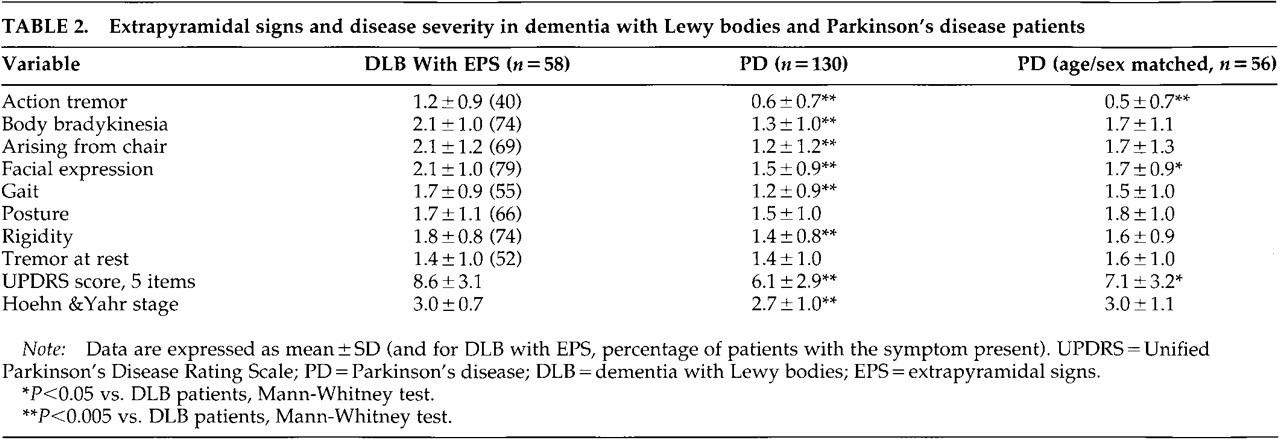

DLB patients with EPS had higher Hoehn and Yahr and UPDRS 5-item scale scores than the PD patients (

Table 2). The severity of action tremor, body bradykinesia, difficulty arising from chair, facial expression, gait, and rigidity were higher in DLB than PD patients. Severity of abnormal posture and tremor at rest did not differ (

Table 2).

In DLB patients, UPDRS and Hoehn and Yahr scores did not correlate with MMSE score, age, age at onset, or duration of disease. Nonsignificant correlations were found between body bradykinesia and current age (r=–0.28, P=0.04) and age at onset (r=–0.24, P=0.07), and between MMSE score and Hoehn and Yahr stage (r=–0.25, P=0.06) and difficulty arising from chair (r=–0.24, P=0.07). In the PD group, increasing age, longer duration of disease, and low MMSE score correlated significantly with increased severity of most EPS measures (all P<0.005).

To adjust for the demographic differences between DLB and PD patients, 56 of the DLB patients were matched on a one-to-one basis with a PD patient according to age (±2 years) and sex. A matching PD patient was not found for 2 of the oldest female DLB patients. The age- and sex-matched PD patients had an earlier age at onset, longer disease duration, and higher MMSE score than the 56 DLB patients (all

P<0.001). The overall level of EPS as measured by Hoehn and Yahr stage was similar in DLB and the age- and sex-matched PD patients, but DLB patients had a higher UPDRS 5-item sumscore than PD patients. DLB patients had higher scores on action tremor and facial expression, whereas no significant between-group differences were found on the other UPDRS items (

Table 2).

Use of Medications

All PD patients received at least one dopaminergic agent, compared with 40 (60%) of the DLB patients with EPS (χ2=60.1, df=1, P<0.001). When only patients taking antiparkinsonian agents were included, Hoehn and Yahr stage was higher in DLB patients (mean=3.2, SD=0.6) than in PD patients (mean=2.7, SD=1.0; U=1,625, P<0.001). Eleven (16%) of the DLB patients were treated with a traditional antipsychotic agent, as compared with 8 (6%) of the PD patients (χ2=5.3, df=1, P<0.05). Sixteen (20%) of the DLB patients had previously received an antipsychotic agent. Six DLB patients (9%) but no PD patients were treated with an atypical antipsychotic (risperidone or clozapine; χ2=12.0, df =1, P=0.001). Nine (13%) of the DLB patients had previously received such an agent.

Severity of EPS as measured with the Hoehn and Yahr scale did not differ between DLB patients ever exposed to traditional or atypical antipsychotics (mean score=3.0, SD=0.6) and those who had never received such agents (mean score=3.0, SD=0.6; P=0.6).

DISCUSSION

The findings in this study demonstrate that extrapyramidal signs are common in DLB patients. In DLB patients with EPS, most EPS assessed were more severe than those in PD patients. Thus, these findings do not support the previous assumptions that EPS are usually mild in DLB patients,

1 but findings are consistent with previous studies using smaller samples

3 and retrospective assessment.

4 On the other hand, 32% of DLB patients, one-third of whom had the diagnosis confirmed at autopsy, did

not have significant EPS. Accordingly, DLB can be diagnosed also in the absence of EPS.

Methodological factors may have influenced the assessment of EPS in DLB. The first and most important of these relates to sampling. The PD group were epidemiologically based and therefore represent the full spectrum of severity, from very mild and early cases to endstage disease. The DLB group, on the other hand, were referrals to a tertiary clinical service with a potential bias for more severely affected cases to be included and early presentations excluded. Second, DLB patients were older and included more men than PD, characteristics that might influence the severity of EPS;

13 however, after matching for age and sex, the DLB patients still had more severe EPS than the PD cases. Third, only PD patients with a good response to levodopa were included, and thus the difference in EPS between DLB and PD patients may be entirely accounted for by a differential response to antiparkinsonian medications. Fourth, the proportion of patients who were currently taking or had previously received neuroleptics was higher in the DLB than in the PD patient group. Medication history thus may have contributed to the prevalence and severity of EPS in DLB patients, although our results suggested that this was not the case.

Data on reliability between centers were not available. Rater variability could therefore influence the principal observations in this study, although raters from different countries can obtain a high rate of agreement in UPDRS scoring despite differences in culture, economics, health systems, and medical standards.

14 It is also possible that PD patients would show more impairment on some of the UPDRS items not assessed in this study. The truncated version of the UPDRS may thus have underestimated the extent of EPS in the PD group. Finally, the Hoehn and Yahr scale does not have the same meaning for PD and for DLB. PD patients usually have a unilateral onset of EPS, and would thus be rated at Hoehn and Yahr stage 1. DLB patients usually begin with bilateral EPS, leading to a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 2, although this does not necessarily mean that they have more severe EPS.

An additional factor relates to diagnostic accuracy for PD and DLB. Some DLB patients may be misdiagnosed as having PD and vice versa.

5 The risk for diagnostic overlap may be increased because PD and DLB patients were diagnosed at two different centers. However, we took care to avoid this. First, only DLB patients with dementia at least one year prior to EPS were included, and one-third of the DLB patients had their diagnosis confirmed at autopsy. Second, only PD patients with EPS before occurrence of cognitive impairment were included. Third, surviving PD patients (75% of the population) were followed for 4 years without evidence of diagnoses other than PD. Finally, we used conservative criteria for PD that have demonstrated a diagnostic specificity for PD of more than 90%.

15The major methodological strength of this study is its large and representative patient samples. The PD group were community-based with a high case ascertainment,

6 and the DLB cohort constitutes one of the largest DLB cohorts reported. Moreover, EPS were assessed with standardized and validated instruments, and care had been taken to include only items that could provide reliable and valid assessments of EPS in DLB.

The neuropathological and neurochemical correlates of extrapyramidal signs in DLB remain to be determined. In vivo studies have demonstrated nigrostriatal degeneration in DLB patients,

16 and an association between nigral cell loss and EPS was found in the subgroup of DLB patients with autopsy in the current study. However, cell loss in the substantia nigra is less pronounced in DLB than in PD,

17,18 and in a recent study no association between nigral cell loss and severity of parkinsonism was found.

19 Thus, mechanisms other than nigral cell loss seem to contribute to EPS in DLB. Cell loss in the striatum may provide an explanation, but we have no morphological evidence for this to date. The residual substantia nigra neurons do not seem to have the same capacity for presynaptic increase in dopamine turnover in DLB patients as in PD patients.

18 When combined with low postsynaptic dopamine D

2 receptors, this could result in greater motor deficits in DLB for the equivalent dopamine loss in PD, which has both presynaptic and postsynaptic compensatory mechanisms.

18 Alternatively, alpha-synuclein pathology in the striatum, or abnormalities in the input of the cholinergic pedunculopontine nucleus to the substantia nigra, may contribute to EPS in DLB. These hypotheses might also explain preliminary reports of the attenuated response to dopaminergic therapy in DLB compared with PD,

20 although the majority of DLB patients do seem to have some response to such therapies.

3,4We found that 68% of a large sample of DLB patients had extrapyramidal signs. Among those DLB patients who exhibited EPS, most symptoms were more severe than in PD patients. To further explore this finding, future studies should compare EPS in medication-naïve PD and DLB patients. Although cognitive impairment and neuropsychiatric symptoms may be the most striking features of dementia with Lewy bodies, the functional impairment caused by severe EPS needs to be addressed and managed. Clinical trials of antiparkinsonian agents in DLB are therefore urgently needed.