In FTD, neuropsychiatric changes are the most prominent symptoms, and they usually precede or overshadow cognitive disabilities.

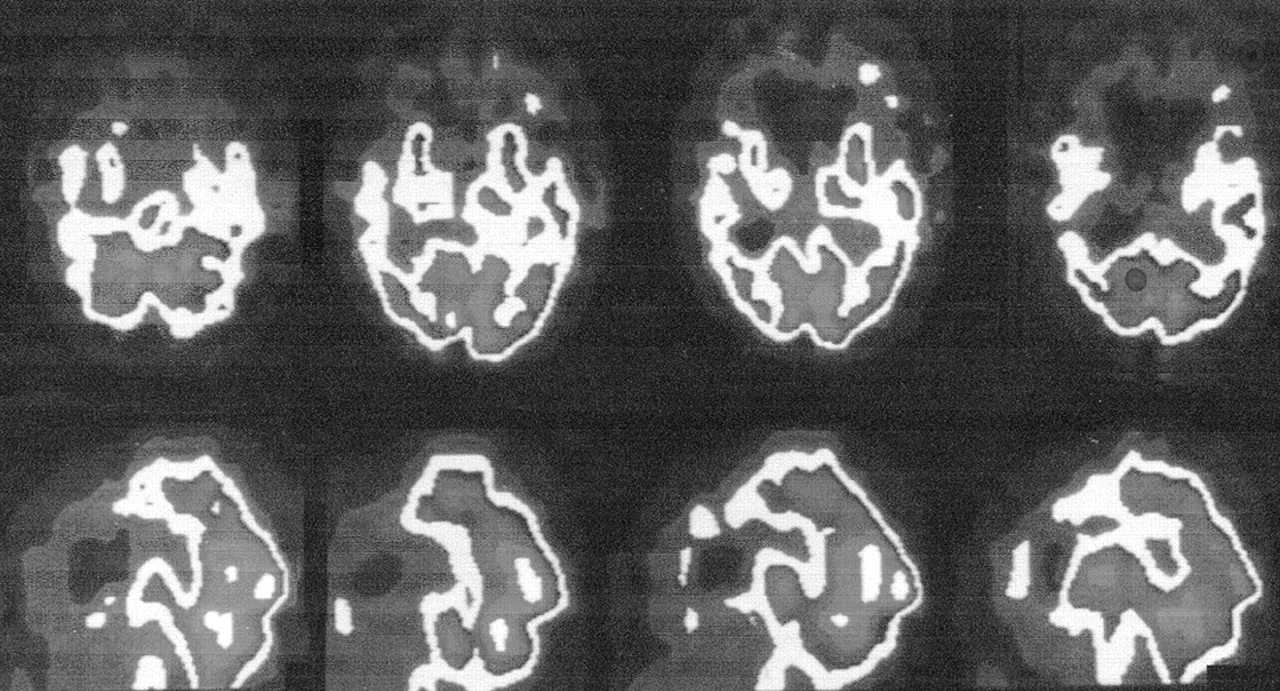

1,2,5 Suspicion of FTD arises when there is a gradual personality change and frontotemporal abnormalities on neuroimaging, particularly frontotemporal hypometabolism.

6 Clinical criteria for diagnosing FTD include the original Lund and Manchester criteria and the more recent Consensus Criteria for FTD (

Table 1).

3,7 Core behavioral features of the Consensus Criteria are impaired social interactions, impaired personal regulation, emotional blunting, and loss of insight.

7 FTD patients also have a range of other behaviors considered “supportive diagnostic features” by Consensus Criteria (

Table 1). These criteria have not been evaluated in a large number of FTD patients previously diagnosed by using Lund and Manchester guidelines. We retrospectively apply the behavioral features from the Consensus Criteria to 53 patients previously diagnosed with FTD and review the literature on the noncognitive neuropsychiatric manifestations of this disorder.

RESULTS

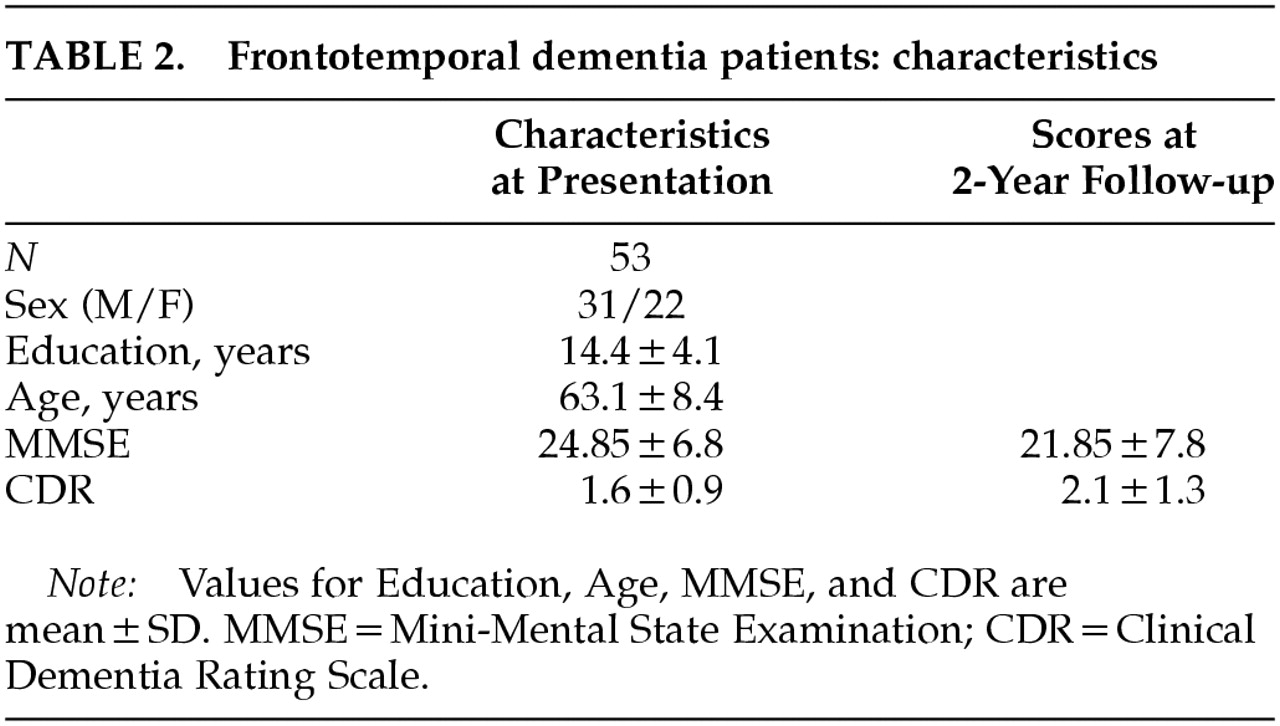

The characteristics of the FTD patients are summarized in

Table 2. The gender ratio is skewed toward males because of the number of VA patients included in this study. Thirteen patients came from the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and 40 from UCLA Medical Center.

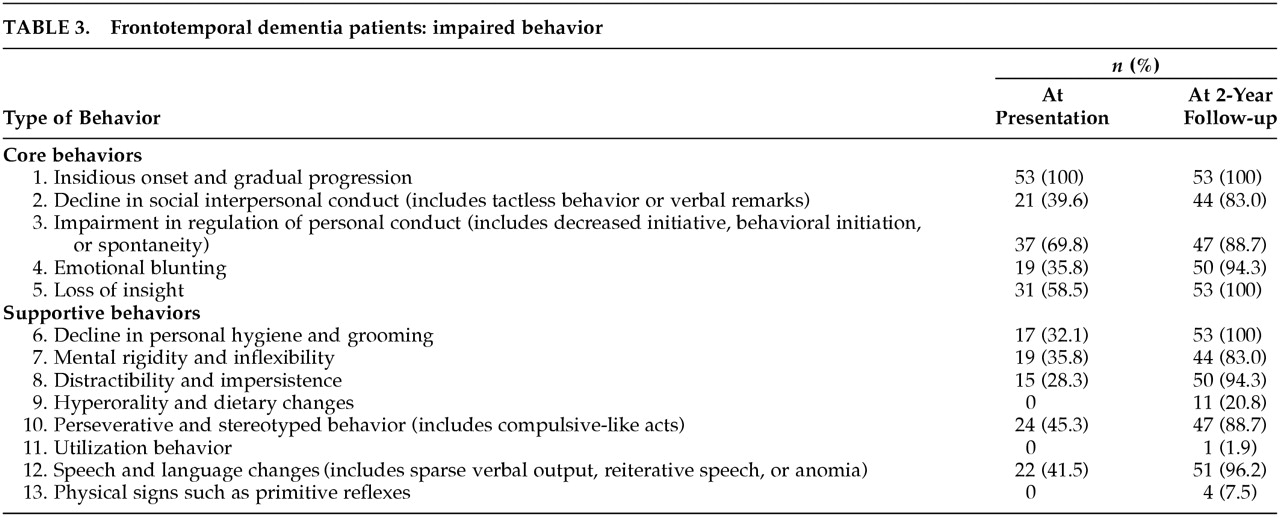

Evaluation of the Consensus Criteria revealed several findings (

Table 3). Only 17 patients (33%) had all five of the core features on initial presentation. All 53 patients had an insidious onset and gradual progression of behavioral changes. Nearly 70% had early withdrawal from usual activities and decreased initiative consistent with impaired regulation of personal conduct;

7 these patients developed passivity, inertia, and inactivity. However, a decline in appropriate social interpersonal behavior was not initially manifest in the majority of FTD patients; tactless behavior or verbal outbursts characterized 40% on presentation. Loss of insight commonly accompanied the decreased initiative, but frank emotional blunting was less common.

Supportive features, including compulsive-like acts and speech changes, were frequent on presentation. There were prominent early stereotypies or compulsive-like behaviors; the most frequent were repetitive checking activities or trips to the bathroom (without other documented cause). The speech and language changes were primarily economy of utterances, where the patient did not initiate conversation or output was limited to short phrases.

7 Responses to questions involved single-word replies or short phrases. Only 2 FTD patients had clear stereotypy of speech, echolalia, or perseverative speech on initial presentation.

On 2-year follow-up, 44 (83%) of the patients had all core criteria and many of the supportive features for FTD. In addition, about 20% developed hyperorality and dietary changes, consistent with the Klüver-Bucy syndrome (KBS). These patients had a tendency to explore their environment with their hands, also consistent with the KBS. None of these patients had hypersexuality, although they were generally disinhibited in sexual and other commentary. On follow-up, 1 patient had utilization behavior and 4 had grasp, snout, or sucking reflexes.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the Consensus Criteria among FTD patients who were initially diagnosed by using Lund and Manchester criteria and functional neuroimaging. Although the Lund and Manchester criteria have been highly sensitive and specific when applied by experienced clinicians,

10 these criteria lacked sufficient precision. They included concepts such as early loss of social awareness and of personal awareness and did not specify the required number of core features (three) for the diagnosis of FTD.

3 The Consensus Criteria appeared to resolve these issues.

7 This study, however, found that only one-third of our FTD patients had all the necessary core features of the Consensus Criteria on initial presentation. The majority of the FTD patients had an early decline in behavioral initiative and insight, but more than half retained social interpersonal conduct and emotional expression until later in their course.

During life, FTD is commonly confused with Alzheimer's disease (AD), but these dementias are distinguishable by clinical features and functional neuroimaging.

2,11 Unlike AD, FTD is usually a presenile disorder with an average age at onset of around 57 years and a usual range of 51 to 63 years.

1,2 FTD, as opposed to AD, more often results in early social incorrectness, disinhibited behavior, loss of personal regulation, self-neglect, compulsive-like behavior, hyperorality, and a progressive reduction in verbal output.

2,5,12–18 On cognitive measures, FTD patients differ from typical AD patients in manifesting early declines in executive functions in the face of relatively preserved memory and visuospatial abilities.

2,5,12–16 The FTD patients in this study, like others in the literature, have a mild-to-moderate memory retrieval deficit on presentation. Functional imaging also distinguishes FTD from AD. In FTD, SPECT and PET scans show evidence of hypometabolism in frontal and anterior temporal regions compared with temporoparietal areas in AD.

19,20 The neuroimaging changes of FTD are often initially asymmetric and worsen over time.

6,21FTD patients usually present with noncognitive neuropsychiatric symptoms that suggest a common underlying qualitative or quantitative loss of self-control.

1 In the literature, the most commonly reported early symptom is worsened social interpersonal behavior.

7,22 This includes declines in tactfulness and manners, violation of interpersonal space, inappropriate touching, and overt sexual behavior or exposure. FTD patients may become impulsive and verbally and physically disinhibited,

23 and some of these patients have aggressive verbal outbursts or assaultive behavior.

2,24 In addition, FTD patients neglect or lose interest in personal hygiene and fail to wash, bathe, groom, or dress appropriately.

7 They may present unkempt and partially clothed, or they may urinate or defecate in front of others. Our results, however, suggest that FTD patients are more likely to become inactive early in the course, with decreased initiation of purposeful behavior, rather than to exhibit early frank social impropriety or disinhibition.

22,25,26 Furthermore, family members often believe that the early personality changes, with inactivity and aspontaneity, represent a form of depression.

FTD patients often manifest emotional blunting, which must also be distinguished from depression. Their emotional blunting overlaps with the other personality changes and produces indifference and apathy rather than sadness or anhedonia. There is a lack of sympathy, empathy, emotional warmth, feelings of embarrassment, or awareness of the needs of others. The expression and perception of emotions, particularly anger and sadness, or of situations depicting a “social dilemma,” are deficient in FTD.

27,28There are other behavioral changes consistent with a “frontal lobe personality” syndrome. These include functional and work capacity due to problems with planning, organization, feedback correction, task completion, and mental flexibility. Abnormal frontal-executive behavior is further reflected in patients' decreased insight and awareness of their disability or the consequences of their behavior. Their corresponding judgment is abnormal, and FTD patients tend to give concrete answers on proverb interpretation. On neuropsychological tests, there is an early compromise of frontal-executive functions and the absence of severe amnesia, aphasia, or perceptuospatial disorder.

13,14 Tests sensitive to ventromedial prefrontal orbitofrontal function show increased risk-taking, increased deliberation times on decision-making, and decreased visual discrimination learning.

29 Although not common among our patients, other frontal behavioral changes may occur in FTD patients, including imitation and utilization behavior or frontal release signs such as grasp or other primitive reflexes.

30In our FTD patients, compulsive-like behaviors were common presenting symptoms.

24,30 Perseverative and stereotyped behaviors encompass simple repetitive acts and verbal or motor stereotypies such as lip smacking, hand rubbing or clapping, counting aloud, and humming. They also encompass complex repetitive motor routines such as wandering a fixed route, collecting and hoarding objects, counting money, and rituals involving unusual toileting behavior.

23,31,32 Some FTD patients have compulsive self-injurious behaviors such as trichotillomania and picking at fingers to the point of excoriation.

33 These compulsive-like acts are not linked to intrusive thoughts or to overt anxiety as in obsessive-compulsive disorder.

As the disease progresses, most FTD patients appear to develop all five of the core symptoms of FTD, and many have elements of the KBS.

2,34 There may be a rapid rate of progression in the first few years after diagnosis. The KBS, which results from bilateral damage to anterior temporal lobes and amygdalae, consists of passivity with loss of affective responses such as fear; oral exploratory behavior and altered dietary preferences; hypermetamorphosis (mandatory exploration of environment); sensory agnosia; and increased sexual activity. The most common symptom of the KBS in FTD is hyperorality manifested as cramming and bingeing, altered food preferences especially for sweets, food fads, weight gain, or increased smoking.

17,34Another common neuropsychiatric manifestation of FTD is a progressively decreased verbal output.

32 Some FTD patients have predominant left hemisphere involvement and present with primary progressive aphasia (PPA) years before other manifestations.

35 Even in the absence of PPA, however, FTD patients usually have decreased speech output and conversation with an economy of utterances (single-word or short phrases). Later, FTD patients can manifest reiterative speech such as stuttering, logoclonia, echolalia, palilalia, and verbal stereotypy, and language changes such as semantic anomia. Eventually, the development of mutism masks any residual underlying language ability.

Other neuropsychiatric symptoms are infrequent in FTD. Psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations are surprisingly rare and were absent in our 53 patients. Nevertheless, there have been reports of patients with an initial schizophrenia-like psychosis or a psychotic affective disorder as a prelude to FTD or to biopsy-proven FTD-Pick's.

36,37 The presence of an affective psychosis may precede the development of FTD by many years.

38 Occasionally FTD is associated with concurrent emotional disturbances—especially depression, but also mania with pressured speech, lability, anger, and irritability.

2Our retrospective assessment of the Consensus Criteria for FTD has several potential limitations. First, the original diagnosis depended on the Lund and Manchester criteria accompanied by functional neuroimaging. A full assessment of the value of clinical criteria for FTD depends on the presence of neuropathological confirmation. Second, the two sets of clinical criteria for FTD, for the most part, attempt to cover similar symptoms, and both sets of criteria provide a great deal of leeway for the interpretation of individual patient behaviors. Third, the clinicians could not be blinded to the original diagnosis in this retrospective study. Finally, judgments had to be made about the presence or absence of emotional blunting. Despite these limitations, this report illustrates the pattern of development of specific behaviors in FTD.

Consensus Criteria for FTD offer guidelines for diagnosis, but further refinement is needed, particularly for patients who lack early changes in social interpersonal conduct. On presentation, core diagnostic features are frequently absent and several supportive features may be more common. Further work is needed to validate the Consensus Criteria and to distinguish behaviors such as decreased initiative and verbal output from depression. Of particular value would be the repeat evaluation of Consensus Criteria on a yearly basis, along with concomitant functional neuroimaging.