All antidepressants possess the ability to exacerbate manic and psychotic symptoms in certain susceptible patients, particularly those with a history of bipolar disorder or other disorders with psychotic features. In a recent retrospective review of 533 consecutive adult psychiatric admissions,

1 we found that 43 admissions (8.1%) were due to antidepressant-associated mania or psychosis. In that study, we applied four criteria: initiation or increase in psychotic or manic symptoms as the primary reason for hospital admission; antidepressant use at the time of admission; recent (within 16 weeks) initiation of antidepressant use as confirmed by chart review and contact with outpatient treaters; and rapid improvement after discontinuation of antidepressants with the addition of a neuroleptic or mood-stabilizing regimen when clinically indicated. We recognized, however, that discontinuation of the antidepressant alone in patients who were otherwise on a reasonable medication regimen would have provided more convincing evidence for the role of the antidepressant in abetting manic or psychotic symptoms. Thus in this study we evaluated the course of manic or psychotic symptoms following discontinuation of antidepressants in a group of patients in which we hypothesized antidepressant exacerbation of symptoms and who were otherwise on an acceptable medication regimen.

METHOD

Sixteen consecutively admitted patients (12 women and four men, ranging in age from 22 to 69 years) who met the following inclusion criteria were studied: manic or psychotic symptoms as the primary reason for admission, medication compliance prior to admission as ascertained by information from referring clinicians, and a medication regimen on admission that included an antidepressant in addition to a mood stabilizer and/or an antipsychotic (at a dosage of at least 300 mg/day of chlorpromazine equivalents). No specified duration of antidepressant treatment was required. Benzodiazepines were not an exclusion criterion. Finally, the regimen had to have been judged independently by two treating psychiatrists to be an acceptable initial clinical treatment regimen if the antidepressants were discontinued. Patients with active substance abuse or serious concomitant medical illness were excluded. DSM-IV diagnoses for the study subjects were major depression with psychosis (n = 5), bipolar disorder with psychosis (n = 1), schizoaffective disorder (n = 3), schizophrenia (n = 5), and psychosis not otherwise specified (n = 2).

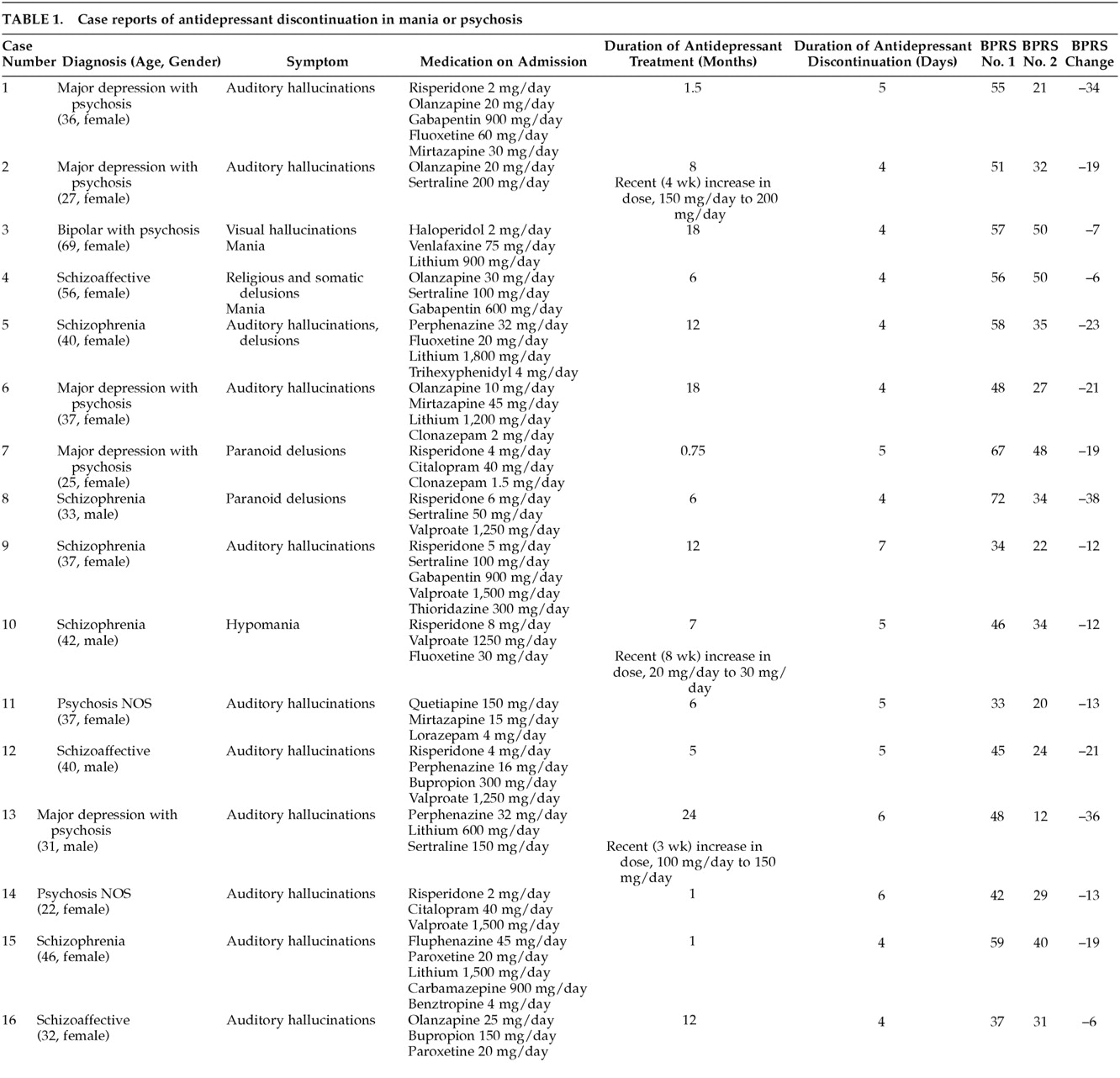

Information for individual subjects about diagnosis, age, gender, major symptoms, and medication regimen on admission are listed in

Table 1. Duration of prior antidepressant treatment is also listed. After hospital admission, antidepressants were immediately discontinued while the rest of the regimen was continued. On the day of admission and again 4–7 days later (mean, 4.7 days) the 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) was administered by trained raters. These scores and the change scores are also listed in

Table 1. Mean scores for the two BPRS evaluations were obtained, and Student's t for paired observations was determined. A rank-order correlation was used to assess the relationship between duration of antidepressant treatment and the BPRS change score. A rank-order correlation coefficient (r′) was calculated in order to assess whether the duration of antidepressant treatment before hospitalization was correlated with improvement after antidepressants were discontinued. In three cases there had been a recent increase in the antidepressant dose, so for three cases r′ was calculated with the longer duration of treatment and again using only the period since the dosage had been changed.

RESULTS

The mean BPRS score before discontinuation of antidepressants was 50.5 ± 11.1 (SD) and after discontinuation, 31.8 ± 11.1. The BPRS declined in every case; the mean decrease was –18.6 ± 10.1 (range, –6 to –38; P<0.001). In all but three cases the BPRS declined by more than 10 points and was clinically significant, even over the relatively short period of observation. The second rating was made on the day before discharge, so a longer period of inpatient observation was not possible.

The rank correlation coefficient (r′) was –0.07 (longer duration in three cases) and –0.28 (shorter duration in three cases). Inspection of the data shows that in several cases discontinuation of the antidepressant even after months of treatment resulted in a significant improvement in the BPRS over a period of 4–7 days. Withdrawal adverse effects of discontinuing antidepressants were minimal and consisted of mild gastrointestinal distress. No major differences in withdrawal effects were noted among the various antidepressants used. Despite the relatively long half-life of fluoxetine, two of the three patients who discontinued fluoxetine improved by more than 20 points on the BPRS.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that discontinuing the antidepressant is a helpful initial step when patients in the schizophrenia-bipolar spectrum are admitted to the hospital because of manic or psychotic symptoms and are otherwise on an adequate psychotropic regimen. These data suggest a possible association between the antidepressant and the exacerbation of the manic or psychotic symptoms. None of our patients became worse over the relatively short period of observation, and 13 of the 16 showed decreases in the BPRS score that were clinically significant (more than 10 points). The rank-order correlation coefficient between duration of antidepressant treatment and reduction in the BPRS score was not significant. This observation suggests that pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic changes may evolve over time with combination treatment (antidepressant plus mood stabilizer and/or neuroleptic) such that the antidepressant effect becomes more significant.

The ability of antidepressants to exacerbate manic and psychotic symptoms has been known for many years. We have recently called attention to some of the early literature describing this phenomenon, beginning with Kuhn's classic paper on imipramine.

2–4 Antidepressant exacerbation of symptoms is the source of a significant number of hospital admissions at our facilities. Such patients demonstrate a pattern of increased plasma monoamine metabolites similar to that of psychotic and manic patients who have relapsed because of medication noncompliance.

5 In this study we found more evidence to implicate the antidepressant in the appearance of manic or psychotic symptoms. In a prospective manner, we made no medication changes other than discontinuing the antidepressant in a group of patients with a relatively new onset of manic or psychotic symptoms who were receiving an antidepressant. Most of them improved significantly in less than a week, indicating that this medication change is relevant even in the present era of brief hospitalizations.

One shortcoming of our study is that we did not have a control group for whom the antidepressant regimen was continued. Clinical priorities made it impossible to create such a group. In addition, our raters were not blind to the antidepressant discontinuation. Another limitation of this study is the lack of exact comparability between the drug regimens that were continued. Although we established minimal criteria for the inclusion of patients in the study, the medication regimens were varied. Nevertheless, the degree and rapidity of improvement in most of the subjects suggests that the drug combinations were generally satisfactory. It should be noted, however, that other factors, such as admission to a stable environment and the attention of clinical staff, could have contributed to the patients' improvement.

In conclusion, discontinuation of antidepressants in newly admitted patients with manic or psychotic symptoms who are otherwise on a satisfactory clinical regimen appears to result in rapid clinical improvement in most instances regardless of the duration of prior antidepressant treatment. Since our study sample was relatively small, further research with larger samples is needed to replicate our findings.