During the past decade, various studies have demonstrated significant deficits in autobiographical and public remote memory in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

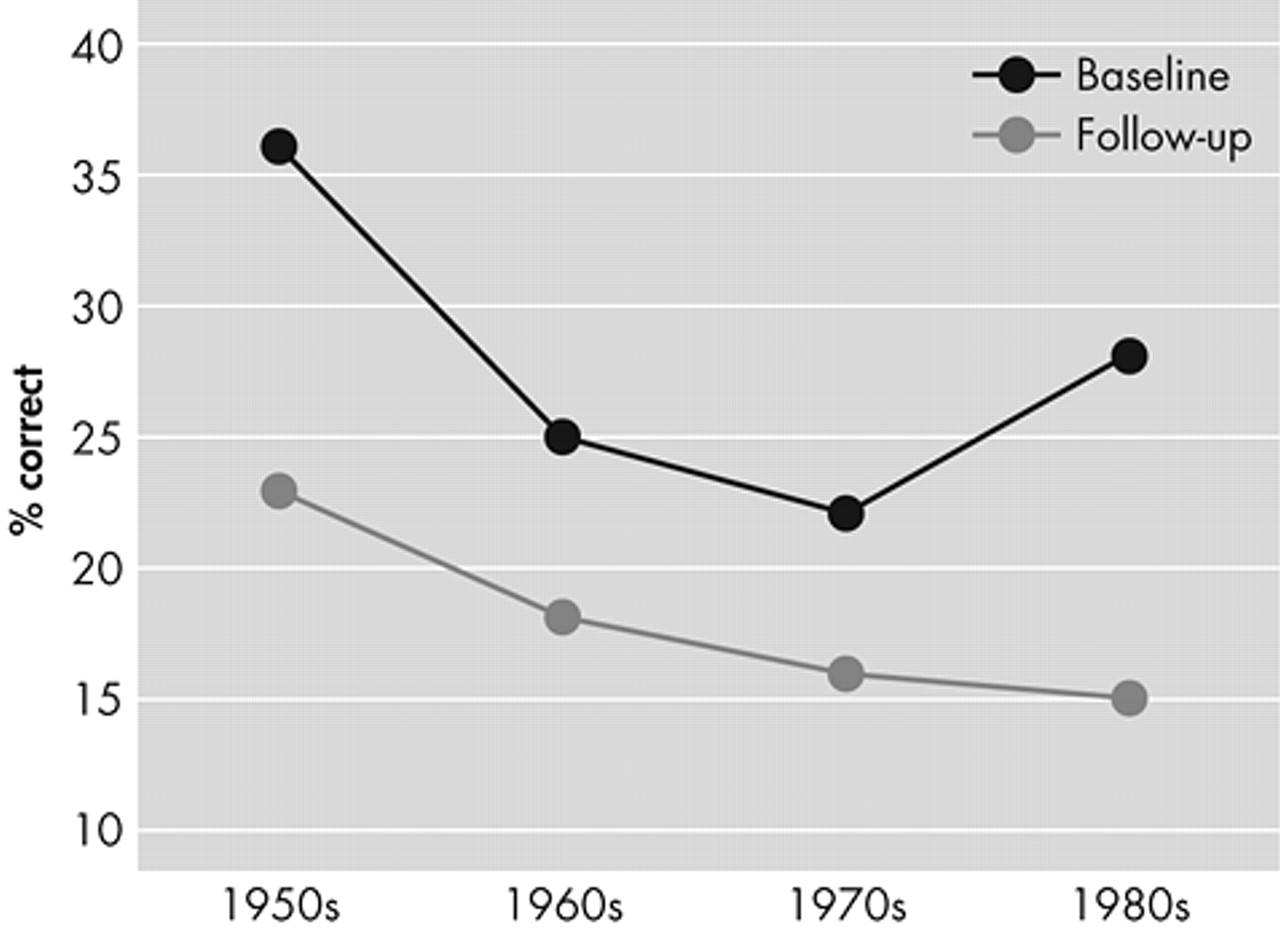

1,2 We reported more severe deficits in AD patients than in age-comparable healthy subjects on both free recall and recognition memory for public events and famous people. These deficits were of similar magnitude across the four decades assessed: 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

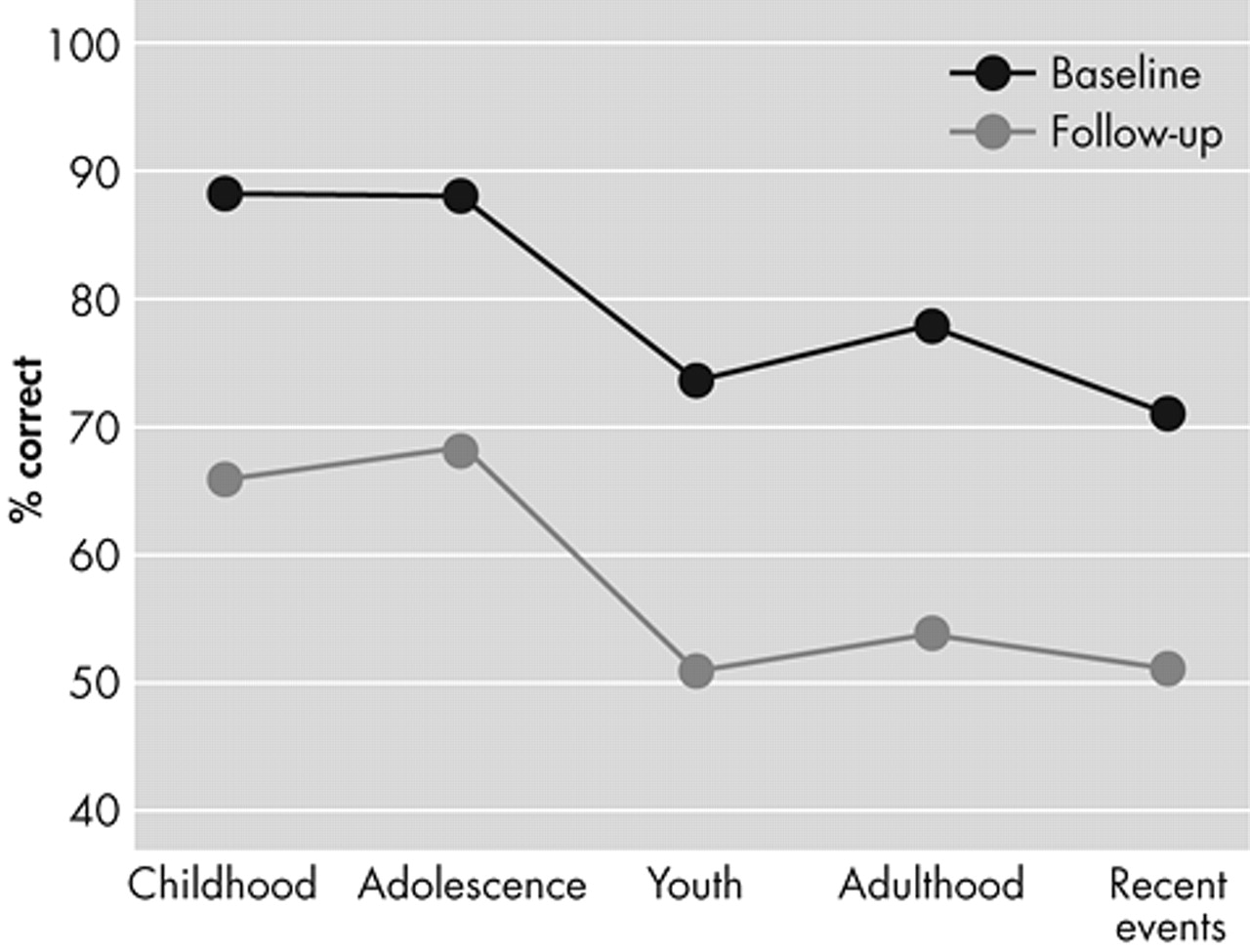

2 AD patients also showed significantly more severe deficits than age-comparable healthy subjects on both the free recall and recognition modalities on the Autobiographical Memory Scale. Additionally, there was a significant gradient, with AD patients showing better recall of early life events (childhood and adolescence) than late life events.

2 On both public remote and autobiographical memory, AD patients showed better performance on recognition than free-recall, suggesting that both retrieval deficits and damage to memory traces may be involved in the mechanism of remote memory impairment in AD.

2Greene and Hodges

1 were the first to conduct a longitudinal (1-year) follow-up study of remote memory in AD. They found that only public memory had a significant decline during the follow-up period, although public and autobiographical memory were impaired in AD. Greene and Hodges assessed autobiographical memory using the Autobiographic Memory Interview, which is based on asking patients to provide personal semantic and incidental data. An important limitation of this approach is that memories produced by patients are not usually verified for accuracy. Lack of autobiographical memory decline in the Greene and Hodge

1 study could have also resulted from the relatively short follow-up period.

To examine long-term changes in autobiographical and public remote memory in dementia, we assessed a series of 21 AD patients and 10 age-comparable healthy subjects twice, with an interval ranging from 24 to 36 months. Both groups were assessed using the Autobiographical Memory Scale, which consists of specific questions from personal history verified by first-degree relatives for accurate responses; the Remote Memory Scale, which assesses memories for famous people and well-known events from four decades (1950s to 1980s);

2 and the Buschke Selective Reminding Test, an examination of verbal anterograde memory.

RESULTS

Background Findings

There were no significant between-group differences in age (AD patients: mean=74.5 [SD=6.2], comparison group: mean=72.1 [SD=9.8]), gender (percentage of women: 57% and 50%, respectively), and years of education (mean=11.0 [SD=4.2] and 11.7 [SD=5.1], respectively).

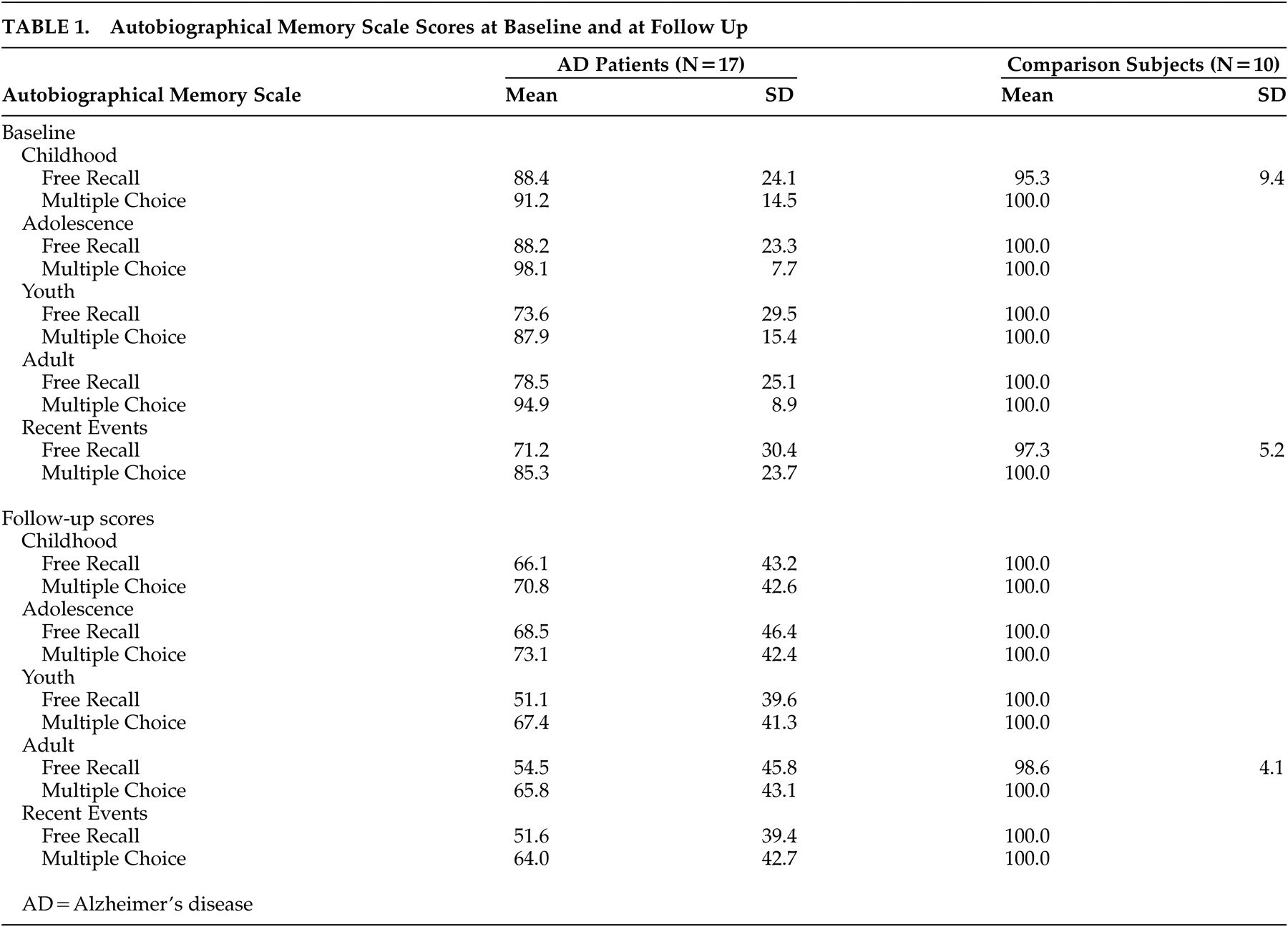

Autobiographical Memory Findings (Table 1)

A 4-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures for the Autobiographical Memory Scale (group [AD versus comparison] × time (initial versus follow-up evaluations) × task (free recall versus recognition) × life periods (childhood, adolescence, youth, adulthood, recent events) showed the following significant main effects and interactions: 1) Group effect (F=8.18, df=1,25, p<0.01); the AD group had a worse performance on the Autobiographical Memory Scale (AMS) than the healthy comparison group, as expected. 2) Task effect (F=10.9, df=1,25, p<0.01); the free recall section was significantly more difficult than the recognition section, as expected. 3) Group × time interaction (F=4.62, df=1,25, p<0.05); the AD group showed a significantly greater decline during follow up than the comparison group. 4) Group × period interaction (F=4.37, df=4,100, p<0.01); AD patients had a significantly better recall for childhood and adolescence than for later periods (

Figure 1).

Public Memory Findings (Table 2)

A four-way ANOVA with repeated measures for the Remote Memory Scale (group [AD versus comparison], time [initial versus follow-up evaluations], task (free recall versus recognition); and decades [1950s–1980s] showed the following significant main effects and interactions: 1) The AD group had a significantly worse performance than the comparison group, as expected (Group effect [F=13.9, df=1,29, p<0.001]). 2) The free recall section was significantly more difficult than the recognition section, as expected (Task effect [F=87.8, df=1,29, p<0.0001]). 3) The AD group showed a significantly greater decline during the follow up than the comparison group. (Group × time interaction [F=5.72, df=1,29, p<0.01]).

To examine the presence of a significant gradient for remote memory deficits in AD for famous people and well known events, we calculated a three-way ANOVA with repeated measures. To avoid floor effects, we excluded AD patients (N=7) with a score of 0 on all four decades at the initial evaluation. We found the expected significant time (F = 25.8, df = 1,22, p<0.0001) and task effects (F = 73.1, df = 1,22, p<0.0001) and a significant time × decade interaction (F = 3.83, df = 3,66 p<0.05), which was the result of a significantly better recall for early than late decades at follow up but not at the initial evaluation (

Figure 2).

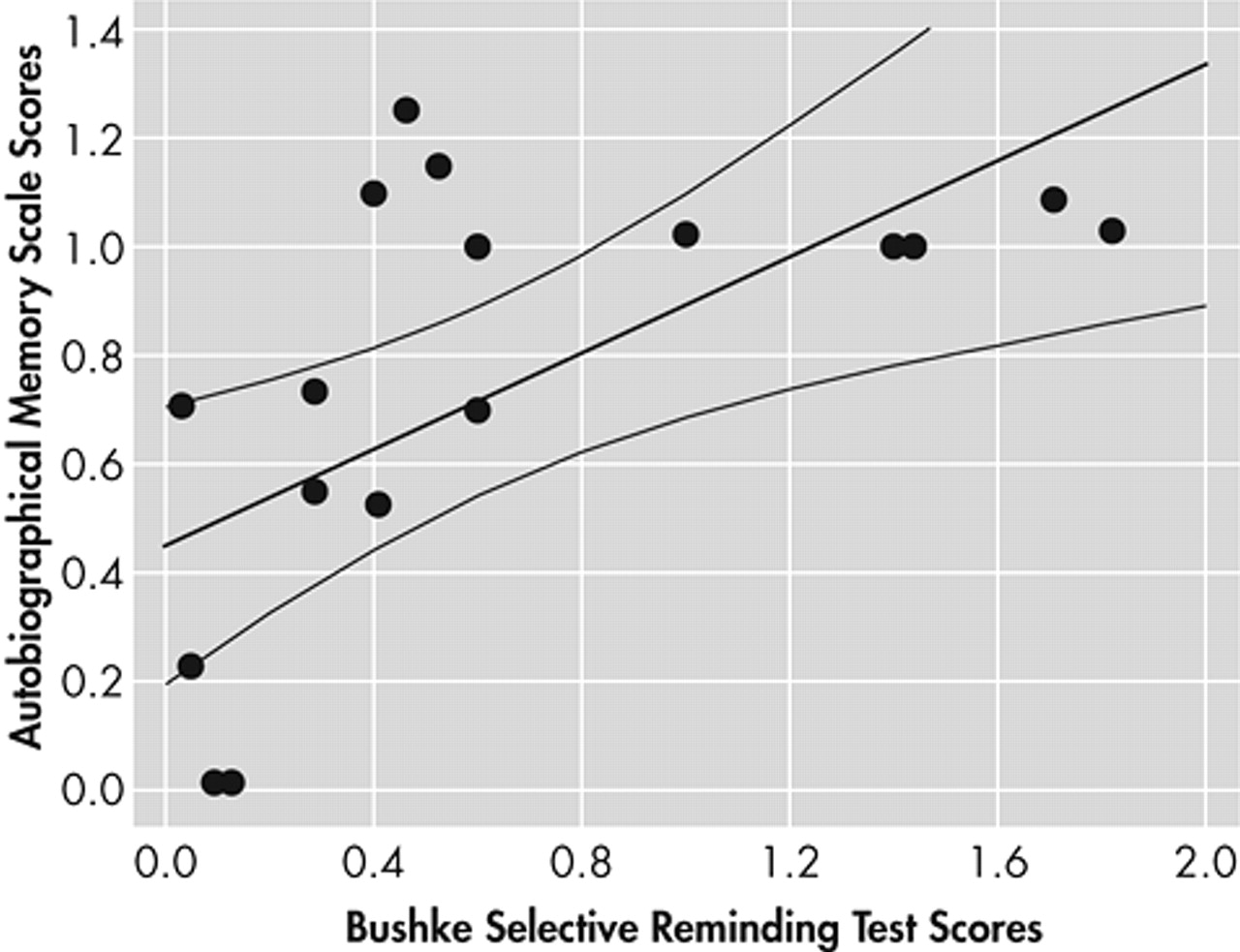

Finally, we calculated the rate of anterograde autobiographical and public remote memory decline in AD using follow-up scores as numerator and baseline scores as denominator. There was a significant correlation between the magnitude of decline in anterograde verbal memory (as assessed with the Buschke Selective Reminding test) and autobiographical memory (Spearman R= 0.63, N=3.28, p<0.01) (

Figure 3), but there were no significant correlations between the magnitude of decline in autobiographical versus public remote memory (R=0.03), between anterograde verbal memory and public remote memory (R=0.21), and between the magnitude of decline in Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores and autobiographical memory (R= 0.39).

DISCUSSION

There are several important findings in this study. First, the AD group showed a significantly greater decline than the comparison group on both types of remote memory during a 30-month period. Second, AD patients showed a significantly better performance on the recognition section of both remote memory tasks than on the free recall sections, suggesting a relatively more severe retrieval when compared to storage deficits. On the other hand, there was a parallel decline on free recall and recognition, suggesting that both retrieval and storage of remote memory data have a similar rate of decline in AD. Fourth, there was a significant recall gradient on the public remote memory test (i.e., significantly better recall of earlier than later decades) at follow up but not at the baseline evaluation, suggesting that the presence of a temporal gradient is significantly related to the stage of illness. Finally, there was a significant correlation between the rate of decline for anterograde verbal and autobiographical memory, but there was no significant correlation between the rate of decline in autobiographical and public remote memory.

Several limitations to the study should be noted. First, our relatively high drop-out rate may have biased our results toward less severe cognitive decline in the AD group. Second, we did not measure the rate of decline in anterograde visuospatial memory or the severity of hippocampal atrophy, and we could not determine whether a compensatory contribution of the right hippocampus may influence correlations between autobiographical and verbal anterograde memory.

In their 1-year follow-up study of 24 AD patients, Greene and Hodges reported a significant decline in famous face and name identification but not in autobiographical memory. They interpreted this finding as supportive of a fractionation of remote memory but acknowledged that a longer follow up may be required in order to show a decline in autobiographical memory. Our study included a 2- to 3-year follow-up period, which was sufficient to demonstrate deficits in memory for public people and events and autobiographical memory. We found no significant correlation between the magnitude of decline on memory for public people and events and autobiographical memory, supporting Greene and Hodges’ hypothesis of separation of public and autobiographical memory.

The pattern of public memory deficits in the Greene and Hodges study was compatible with a loss of storage of memory traces, with retrieval deficits making a minor contribution to the memory impairment. We found no task (i.e., free recall versus recognition) × time interaction, demonstrating a similar decline for both conditions and suggesting that storage and retrieval abilities for public memory have a parallel decline in AD. Given the lack of significant decline in autobiographical memory in the Greene and Hodges study, the presence of a relative impairment of access and storage for autobiographical material could not be determined. We found a nonsignificant task × time interaction for autobiographical memory, suggesting a similar decline for access and storage of autobiographical memories.

The presence of a temporal gradient for public remote memory, namely a better recollection of early versus late memories, has been reported by some

6–8 but not all studies.

9 Nestor et al.

10 recently suggested that the presence of a significant gradient may depend on the stage of illness and sample size. In our baseline study of remote memory, we could not find a temporal gradient for the recall of famous people and well-known events.

2 However, the present follow-up study demonstrated a significant decade × time interaction, which resulted from a faster decline in the recall of recent as compared to earlier decades for the follow-up assessment only. While supporting the presence of a temporal gradient for public remote memory in AD, our study suggests that this phenomenon is absent in the early stages of the illness.

Fama et al.

11 found significant associations between poor performance on the recognition section of a public remote memory test and smaller parieto-occipital cortical volumes and between poor anterograde (but not autobiographical) memory and smaller hippocampi volumes, suggesting a dissociation between cortically mediated remote memory and hippocampally mediated anterograde memory. Fama et al. also reported a dissociation between anterograde and retrograde memory performance in AD as well as no significant association between the severity of dementia and remote memory deficits.

12 Our initial study demonstrated no significant association between deficits on a test of verbal anterograde memory and deficits on tests of autobiographical and public remote memory.

2 However, we found a significant correlation between the magnitude of decline in anterograde verbal memory and in autobiographical memory. Taken together, these findings suggest the disruption of independent mechanisms of anterograde and autobiographical memory deficits early in AD but a common final pathway at later stages of the illness.

There is consistent evidence that anterograde memory deficits in AD result from medial temporal lobe pathology, but the pathological basis of autobiographical amnesia is less well known. A recent study by Maguire and Frith

13 used functional MRI to examine brain activations during the retrieval of real life autobiographical event memories in young and elderly healthy adults. They found significant unilateral hippocampal activation in young adults but bilateral hippocampal activations in older adults. Future studies should examine whether both anterograde and autobiographical memory deficits result from neuropathological changes in different but close brain regions (e.g., medial and polar temporal regions, respectively) and whether extension of those changes may produce a parallel long-term decline in different memory domains.