Sudden outbursts of involuntary, exaggerated laughter and/or crying have been described in patients with certain neurological disorders since the 19th century. As early as 1872 Charles Darwin noted, “Certain brain diseases, such as hemiplegia, brain-wasting, and senile decay, have a special tendency to induce weeping.”

1 In 1924, Kinnier Wilson described the core features of this syndrome. He noted that for these patients, their displayed emotions were often out of proportion to the stimuli that evoked them, and inappropriate to the social context in which they occurred. To account for this dissociation between outward emotional expression and underlying mood, Wilson proposed a hypothesis that has come to be known as the “disinhibition” or “release” hypothesis. Wilson hypothesized that the anatomical basis for this syndrome was the loss of voluntary, cortical inhibition over brainstem centers that produced the facio-respiratory functions associated with laughing and crying. This loss of cerebral control resulted in a dissociation of affective displays from the subjectively experienced emotional states.

2Several different terms have been used for this clinical syndrome. Clinicians have used terms such as “pathological laughing and weeping,” “emotional lability,” “pseudobulbar affect,” “emotional incontinence,” “pathologic emotionality” and others to refer to these disorders.

3 A key terminological issue is the implied degree of dissociation between the subjective feelings and the displayed emotionality. The term, “emotional lability” implies that the episodes of affective display are excessive in frequency or amplitude, but congruent with the underlying, subjective mood.

4–9 “Emotional lability” also is generally considered to invoke a broad range of emotions, such as irritability, anger, and frustration in addition to laughing or crying.

4,10–11 Episodes which are termed “emotional lability” are generally expected to be less stereotyped than those rapid, paroxysmal episodes which have been called “pathological laughing and crying,”

4,10–11 The term “pseudobulbar affect (PBA)” has generally been used more broadly, to refer to syndromes of exaggerated affective display which can be either mood incongruent

5 or mood congruent.

12 We will preferentially use the term, “Pseudobulbar Affect” in this article.

The neuropathological and neurophysiological substrates of the PBA syndrome are not completely understood. Kinnier Wilson hypothesized that the syndrome was caused by bilateral corticobulbar motor tract lesions, which uncoupled cranial motor nerve nuclei and supranuclear integrative centers from their cortical control.

5,13–16 Subsequent authors have emphasized regulatory functions attributable to temporal and infratemporal limbic system centers for emotional expression and emotional experience.

3,4,14,17 The PBA syndrome has been reported in a variety of neurological diseases, including ischemic stroke, brain trauma, motor neuron disease, multiple sclerosis, and the dementias.

18 Diminished serotonin metabolism by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) has been reported in some patients with PBA.

82 Low cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) homovanillic acid has been reported in a cohort of stroke patients with PBA.

19 A summary of anatomic findings in 30 cases indicated that the lesions always involved systems with motor functions, and that the lesions were always multifocal, or bilateral.

84 The most common neuroanatomic structures involved were the internal capsules, the substantia nigra, the cerebral peduncles, and the pyramidal tracts. Imaging studies suggest that, occasionally, single lesions in the brainstem or posterior fossa can generate the PBA syndrome.

20–26Parvizi et al. have recently proposed an alternate mechanism for uncontrollable laughing and crying.

27 They suggest that pathways from higher cortical association areas to the cerebellum are involved in the adjustment of laughing and crying responses to appropriate environmental cues. They propose that lesions that interrupt either cortico-cerebellar communication or cerebellar communication with effector sites that produce emotional responses (e.g., the motor cortex or brainstem) can disrupt cerebellar modulation of affective displays, and produce the PBA syndrome.

PREVALENCE OF PBA SYNDROMES

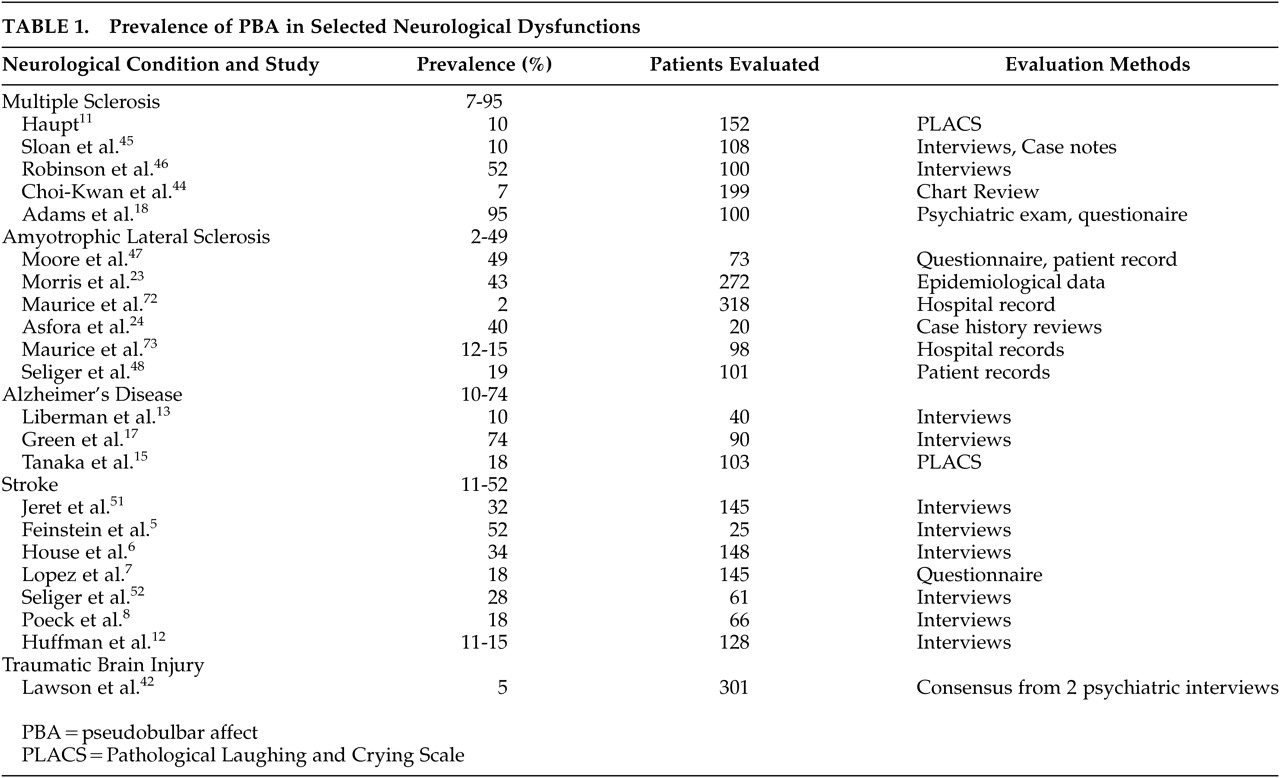

Estimated prevalence rates of PBA in patients with various neurological disorders are listed in

Table 1. There is significant variability in reported prevalence rates, both between and within syndromes. Some of this variability is almost certainly due to syndrome specific neurobiological factors, but some is undoubtedly due to variable approaches to case finding and case definition. Higher prevalence rates in

Table 1 are associated with definitions of PBA which include both mood congruent and incongruent episodes,

9,28 and lower rates are reported when narrower criteria are used.

5Multiple Sclerosis

Recent studies suggest a lifetime prevalence of PBA of approximately 10% in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients (

Table 1). PBA is generally associated with later stages of the disease (chronic progressive phase).

3,5,29 PBA in MS patients is associated with more severe intellectual deterioration, physical disability, and neurological disability.

30,31Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Reports of the prevalence of PBA in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients range from 2% to 49% among 6 studies (

Table 1). The most recent study with 73 patients found a 49% prevalence.

32 PBA does not appear to be associated with duration of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, but does seem to be associated with the presence of bulbar symptoms.

16,32,33Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

Prevalence reports of PBA in AD patients range from 10% to 74% (

Table 1). A mid-range study was performed by Starkstein et al., who used the Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale (PLACS) instrument to identify PBA cases.

9 These investigators found that 21% of AD patients had episodes in the presence of a congruent mood disorder (termed emotional lability), and 18% had mood-incongruent episodes (termed pathological laughing and crying), resulting in a total of 39% that had either type of episode (termed pathological affect).

9Stroke

PBA is one of the most frequently reported poststroke behavioral syndromes, with a range of reported prevalence rates from 11% to 52% (

Table 1). The higher prevalence rates tend to be reported in stroke patients who are older, who have a history of prior stroke, and who have subcortical strokes involving the internal capsules and neighboring basal ganglia.

20,34 PBA associated with stroke may have a delayed onset, making neuropsychiatric assessment in the immediate, poststroke period insensitive.

20,35,36 For many stroke patients, there appears to be progressive amelioration of PBA symptoms over time.

3,6,35The relationship between poststroke depression and PBA is complicated, because the depressive syndrome also occurs with high frequency in stroke survivors.

83 Poststroke patients with PBA are more depressed than poststroke patients without PBA, and the presence of a depressive syndrome may exacerbate the weeping side of PBA symptoms.

6,37 The predilection of lesion location in left frontal areas reported by Robinson in poststroke depression does not appear in the neuroanatomic studies of PBA above.

Traumatic Brain Injury

One study of 301 consecutive cases in a clinic setting reported a 5% prevalence.

38 PBA occurred in patients with more severe head injury and coincided with other neurological features suggestive of pseudobulbar palsy.

Other Conditions

PBA has also been observed in association with a variety of other neurological disorders, including Parkinson’s disease, brain tumors, Wilson’s disease, syphilitic pseudobulbar palsy, and various encephalitides.

3,39 Rarer conditions associated with PBA include gelastic epilepsy, dacrystic epilepsy, central pontine myelinolysis, olivopontinocerebellar atrophy, lipid storage diseases, chemical exposure (e.g., nitrous oxide and insecticides), fou rire prodomique, and the puppetlike syndrome of Angelman.

3,40NEUROPSYCHIATRIC IMPACT OF PBA

The natural history of PBA is not precisely known, and may depend largely upon the nature of the underlying neurological disease. In one cohort based study of poststroke patients, there was some fluctuation in the number of patients demonstrating PBA, from 15% during the immediate poststroke period to 11% at 1-year followup.

3 After head injury, the syndrome tends to persist and become chronic without treatment.

41PBA can significantly impair social and occupational function.

4,14,17,40 The outbursts of PBA may become associated with secondary phobias and social withdrawal.

40 Reviews consistently conclude that PBA can be profoundly disabling in social situations and considerably impact psychological well being.

4,40,42–43 PBA may be associated with aspiration risks, and contribute to medical morbidity.

42 Decreased poststroke sexual activity has been described in patients with PBA.

44 Not all investigators have reported adverse social functional effects from PBA. Feinstein et al. reported that multiple sclerosis patients with PBA (N=11) did not have higher social dysfunction scores on the General Health Questionnaire compared to controls (N=13).

5 PBA has also been reported to have adverse effects on occupational function, and to interfere with rehabilitation therapy programs.

4,38,41,45Patient Testimonial

A brief narrative is provided here from a 55-year-old woman with PBA as a consequence of ALS that portrays the magnitude of distress and even physical pain that accompany PBA.

13“I have … been aware while it was happening that I was not as upset or as sad as my crying would imply, nor as uproariously amused as my uncontrollable laughter would indicate. Such episodes of laughter and tears may have slight connection with my actual frame of mind or the feeling which is actually mine at the time. In fact, I usually become very frustrated and angry at my inability to put a halt to such ridiculous behavior!

I begin to smile, but the smile becomes an exaggerated grin, which attaches itself, fixedly, to my face, and I have to use all my powers of concentration to remove the embarrassing grimace. If I yield to the impulse, it becomes the onset to equally uncontrollable giggles, which in turn so embarrass me, that I become angry, humiliated, and subject to uncontrollable tears—it is a vicious, see-sawing circle!

…I am mortally afraid of squealing bawls. They destroy me—they weaken and crumble me…those deep debilitating agonizing episodes.…You have no idea how terrible it is when the crying is fully triggered and takes hold like a seizure. I cannot control any of it. I simply disintegrate and it is not only emotionally horrible with me, it is physically painful and debilitating.”

MEASUREMENT INSTRUMENTS

Three standardized rating scales exist, which can be used as screening instruments, or as more objective measures to monitor treatment.

Robinson et al. developed the PLACS, an interviewer-rated instrument, that is both valid and reliable in quantitatively assessing the severity of PBA symptoms in stroke patients.

46 The investigators further demonstrated its usefulness in measuring outcomes in a double-blind treatment study. The PLACS quantifies aspects of laughter and crying, such as the relationship between the episodes to external events, duration, degree of voluntary control, inappropriateness with respect to emotions, and degree of resultant distress. Eight items relate to laughing and eight to crying. For each of the items, the examiner scores the severity of the symptom on a 0–3 point scale. Scores on all items are totaled to obtain an overall score. A cutoff score of 13 or higher is recommended to identify patients with PBA.

Moore et al. have developed and validated the Center for Neurologic Study-Lability Scale (CNS-LS), a self-report measure of “affective lability” in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and MS.

47,85 The CNS-LS is short, and easily administered. The CNS-LS consists of two subscales: one for laughter (4 items) and one for tearfulness (3 items). An auxiliary subscale measuring labile frustration, anger, and impatience was also developed, but not fully validated. Each item asks respondents to indicate on a five-point scale (where 1=applies never and 5=applies most of the time) how often they experience symptoms of PBA. A score of 13 on the CNS-LS accurately predicted independent diagnosis of PBA by neurologists for 82% of participants in the Moore study.

47The group at King’s College in London has published performance characteristics of their Emotional Lability Questionnaire (ELC).

81 The ELC has a self-rated version and an independent-rated version, and is designed to be more sensitive to PBA syndromes with low frequencies of emotional events.

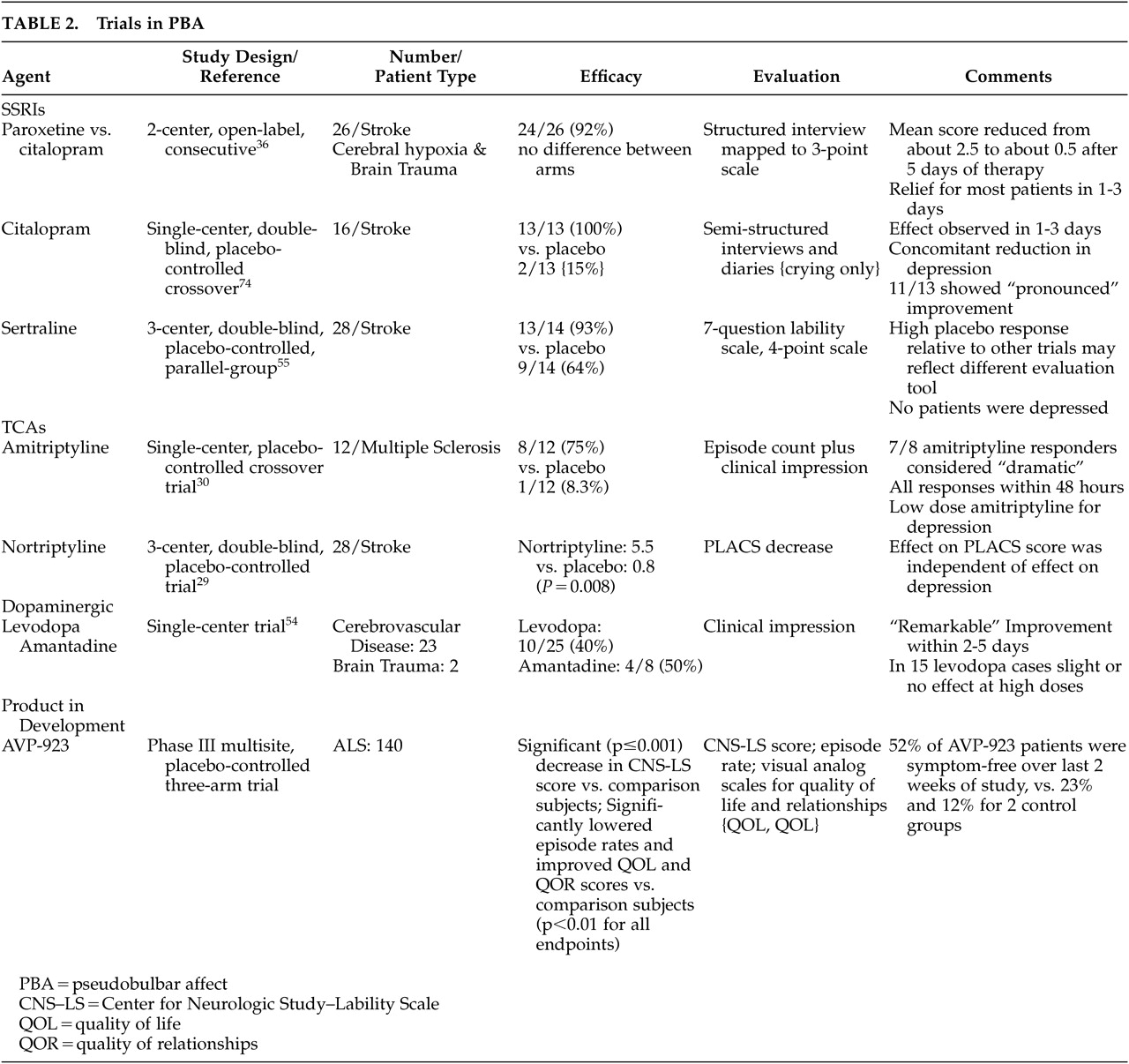

TREATMENT WITH CURRENTLY AVAILABLE AGENTS

At the present time no drugs have Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of PBA. There are clinical reports of therapeutic benefit from both antidepressants and dopaminergic agents. Small comparative trials (Table 2) suggest that tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants have efficacy. A large number of individual case reports also suggest that various antidepressants improve PBA.

39,45,48–64 The therapeutic response which occurs with antidepressants often occurs early after initiation of treatment, usually within 2 to 3 days

65,66 Relatively low doses of these agents may be effective in PBA, compared with antidepressant efficacy.

Dopaminergic agents, including

L-dopa and amantadine, have also been reported to have efficacy for the PBA syndrome.

19,67,68 The response to

L-dopa is not robust, however, with only 10 of 25 patients responding in the Udaka study.

19None of these agents has been shown to be effective in large, well-controlled trials using objective measurement scales for PBA, and the tricyclic antidepressants are associated with treatment limiting adverse effects in many cases. There is evidence to suggest that most patients with even severe PBA symptoms at the present time remain untreated.

3,6,45,49,69 We believe that there is a need for new therapeutic options for the PBA syndrome.

Novel Therapeutic Option

Dextromethorphan is a well known, nonopioid antitussive agent, which has recently attracted interest because of a variety of other neuropharmacological properties that it may have.

70 Dextromethorphan is a potent sigma-1 receptor agonist, as well as uncompetitive

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist.

71–74 The pharmacologic properties of sigma receptor systems are not yet fully known, but these systems are densely distributed in limbic and motor related systems of the CNS.

75 It is hypothesized that some sigma subsystems may be widely involved in behavioral responses such as learning, response to stress, mood disorders, dependence, and others.

73A potential problem in oral delivery of dextromethorphan in humans has been its pronounced, first-pass elimination by the liver.

76 This rapid metabolism can be blocked by quinidine, however, a cytochrome P450 2D6 inhibitor.

76,77 Quinidine doses that block metabolism of dextromethorphan are 10- to 20-fold lower than those routinely used to treat cardiac arrhythmias.

76,78 Repeated dosing of dextromethorphan combined with low dose quinidine appears to have no adverse cardiac effect.

77This dextromethorphan/quinidine product was proven effective and safe in palliating PBA in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients in a large (N=140), placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial.

79 In this amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinical trial, AVP-923 significantly (p<0.001) improved PBA symptoms on the CNS-LS validated self-assessment tool following 30 days of treatment compared to dextromethorphan or quinidine alone. Furthermore, AVP-923 significantly decreased the frequency of laughing and/or crying episodes (p<0.001 versus dextromethorphan or quinidine).

69 Quality of life (QOL) and quality of relationships (QOR) also improved as measured by changes in visual analogue scale scores. Commonly experienced AEs that were more common than in the control treatments included nausea, dizziness, and somnolence. More than 90% of subjects who tolerated the drug for the first 5 days of dosing completed the 30-day treatment period. A placebo-controlled study of PBA in 150 patients with MS has recently been completed, and similar results were reported.

86The mechanism by which dextromethorphan relieves PBA symptoms is unknown. It may involve dextromethorphan’s agonist action on sigma receptors in brainstem and cerebellar neural networks. Sigma-1 sites are particularly concentrated in the brainstem and cerebellum,

73,75 and dextromethorphan has been shown to preferentially bind to these brain regions.

70,80 Dextromethorphan may exert a more selective action on brain regions implicated in emotional expression. Altered pharmacokinetics of dextromethorphan combined with quinidine in AVP-923 may offer a potentially more selective approach to the treatment of PBA.

77CONCLUSION

The Pseudobulbar Affective Syndrome has long been recognized as a relatively discrete neuropsychiatric disorder, but it is almost certainly underrecognized in clinical settings. There has not been a general consensus concerning the treatment of PBA. A dextromethorphan/quinidine combination is under development as a treatment for PBA, suggesting the first application of a sigma receptor agonist in behavioral disorders. If further clinical trials confirm the usefulness of this new agent in PBA, and FDA approval can be obtained, a new category of neurotropic agents may be introduced into the therapy dictionary of neuropsychiatry.