Psychogenic movement disorders (PMDs) include various abnormalities of motor functioning that are not explained by an identifiable neurological disease and that appear to result from an underlying psychological illness. Although PMDs are not included within APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR),

1 many patients with PMDs meet diagnostic criteria for a somatoform disorder, such as conversion or somatization disorder. About 3%–4% of patients seen in subspecialty movement disorder clinics have a PMD;

2–4 yet, little is known regarding their pathophysiology, and the absence of a defined neurobiology has slowed progress in PMD diagnosis, prognostication, and treatment. Indeed, at present, there are no proven therapies for PMDs, and patients often suffer morbidity related to unnecessary and costly medical and surgical interventions targeted toward “organic” disorders.

5,6 Since PMDs result in levels of disability and impaired quality of life similar to neurodegenerative disease,

7 more effective therapies are needed.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) devices emit low-voltage electrical currents to the skin and are widely used to treat acute and chronic pain related to various conditions, including musculoskeletal diseases, neuropathy, surgery, and childbirth.

8,9 Although the mechanism of action and optimal parameters of TENS are not established, some data suggest that TENS modulates both sensory and motor transmission within the CNS.

10–12 In light of its potential to modify motor-cortical excitability, TENS has been investigated in patients with several movement disorders, including idiopathic dystonia,

13–15 tremor,

16 propriospinal myoclonus,

17,18 posttraumatic dystonia,

19 and “belly dancer's dyskinesia.”

20 Although not all patients benefited from TENS,

16 some, particularly those with dystonia, did improve.

13–15,17,19,20 In the present study, we assessed the efficacy of TENS in patients with probable or clinically-established PMDs.

21 The rationale for the study was partly based on the fact that, in several patients with TENS-responsive movement disorders, a psychogenic etiology was considered;

17,19,20 these include two recently reported patients who meet diagnostic criteria for a PMD.

18 Furthermore, since transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) studies have shown that psychogenic and organic dystonia exhibit similar neurophysiological abnormalities, as compared with controls,

22,23 it is plausible that the neuromodulatory effects of TENS might alleviate both disorders. Also, patients with PMDs often have associated pain that can be disabling and difficult to treat with standard pain medications, and the analgesic effects of TENS may be helpful for this symptom, as well. Finally, TENS has not been associated with significant adverse effects, making the anticipated risk-to-benefit ratio favorable.

RESULTS

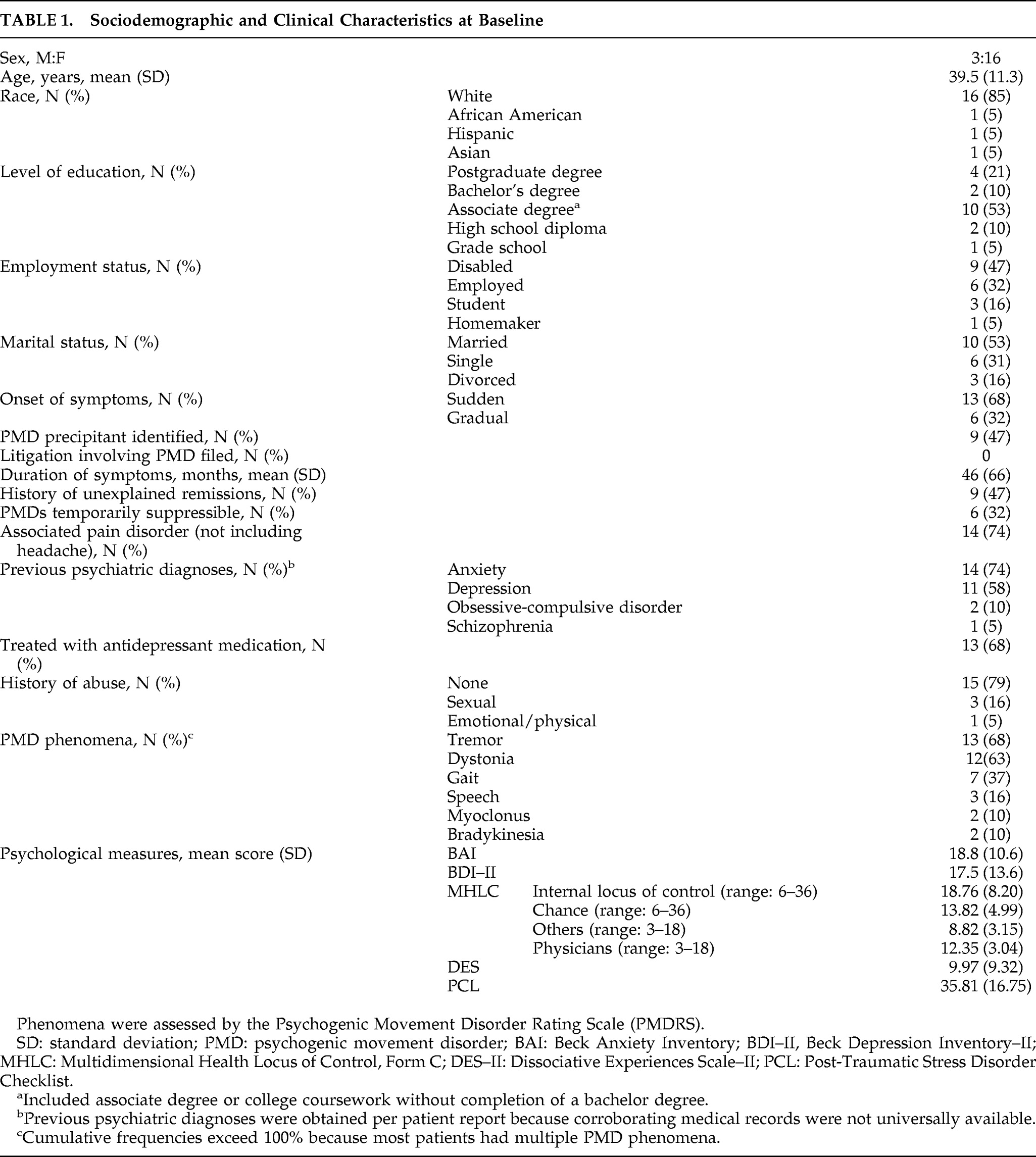

Sociodemographic and baseline clinical characteristics are provided in

Table 1. On psychometric testing, 47% met the clinical cutoff score for depression on the BDI–II; 17% were classified as mild, 5% as moderate, and 28% as severe. One patient with severe symptoms of depression endorsed the item, “I would like to kill myself;” three patients (one with moderate and two with severe symptoms of depression) reported having thoughts about the possibility of suicide, but never being able to carry out the act. Mild, moderate, and severe symptoms of anxiety were reported by 22%, 33%, and 28% of patients, respectively. Few dissociation-type experiences were endorsed by patients, and only one patient met clinical criteria for dissociation on the basis of the DES. In contrast, 47% of the sample met the cutoff score for PTSD on the PCL; 22% of the sample reported a history of abuse, which was positively correlated with meeting the clinical cutoff score on the PCL (p<0.001). Results of the MHLC showed that patients perceived internal factors as having a larger influence on their movement than did chance (p<0.03) and others (p<0.04).

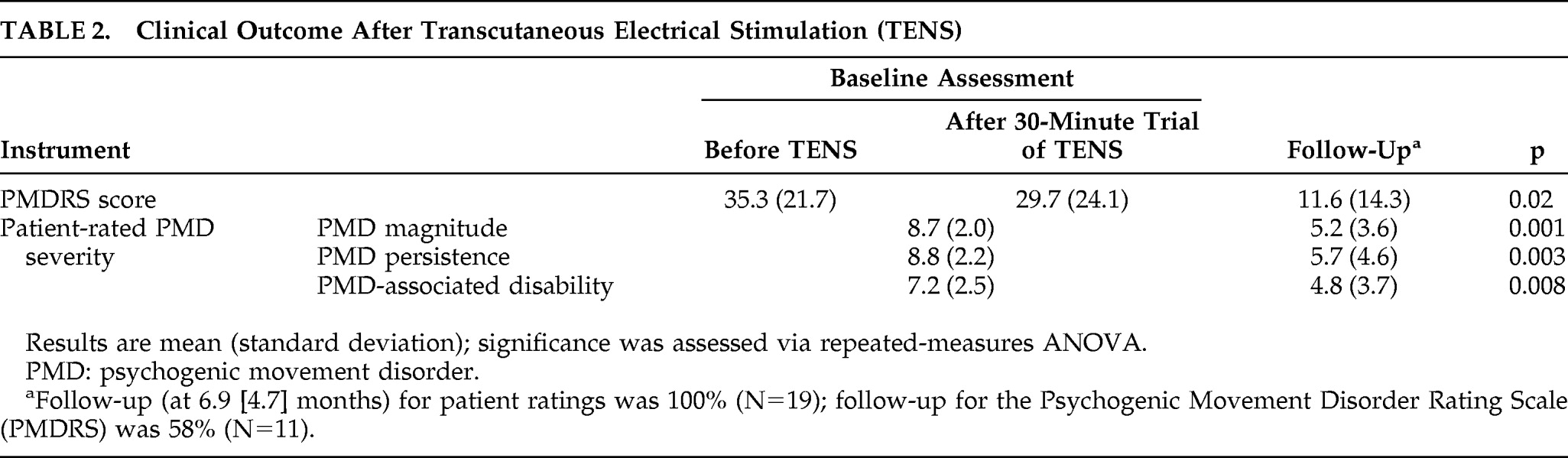

Although 15 patients (79%) elected to continue TENS as outpatients, only 5 demonstrated a robust (>50%) improvement in PMDRS score during the initial trial of TENS in the clinic. Two patients had a 20%–30% improvement, and two had a transient >25% worsening in PMDS score. In the remaining 10 patients, the PMDRS score changed <5% from baseline during the initial trial of TENS in the clinic. Eight (42%) participants failed to return for a follow-up assessment in the clinic, including all four patients who had elected not to continue outpatient TENS. However, all patients who did not return provided follow-up ratings of PMD magnitude, persistence, and disability by phone. At a mean follow-up of 6.9 (SD: 4.7) months, there was a significant improvement in both PMDRS scores and all self-rated outcome measures compared with baseline (

Table 2). All five patients who experienced a >50% improvement during their first session of TENS had no visible abnormal movements at follow-up. Linear-regression analysis to determine which demographic, clinical, and psychometric variables correlated with PMD prognosis in this patient cohort found that a short PMD duration best predicted a favorable outcome (β=0.211 and p=0.001). Apart from the transient exacerbation in PMD severity noted above, no adverse effects were reported during the study.

DISCUSSION

Conventional therapies for organic movement disorders are usually ineffective for PMDs, and published treatment data for PMDs are regrettably sparse.

5 Modest evidence supports psychodynamic psychotherapy,

34 and antidepressants appear to reduce PMD severity in patients with a comorbid mood or anxiety disorder.

35 Cognitive-behavioral therapy has proven helpful for patients with other “medically unexplained symptoms” but has not been adequately studied for PMDs specifically.

36 Some centers advocate a combination of psychotherapy and physiotherapy.

37 In this pilot study, we evaluated TENS both as a short-term (clinic-based) intervention and as a continued (outpatient) treatment for PMDs. We found a statistically significant improvement in PMDRS severity scores at follow-up, attributable largely to a complete PMD remission in approximately one-fourth of patients. Patient-rated assessments of PMD magnitude, persistence, and disability likewise improved. Similar to previous studies of TENS for other indications, we did not observe serious or permanent adverse effects related to the therapy. Symptoms of two patients, however, temporarily worsened during their initial TENS trial, and further work is needed to confirm the safety of TENS for PMDs.

The course of PMDs is more variable than most movement disorders, and improvements in PMD severity generally are infrequent and modest,

38–41 with remission rates in the range of 5% to 15%.

40,42,43 A more favorable (but certainly not benign) disease course has been reported at some movement-disorder centers, but what might account for this variation still awaits clarification.

2,21,44 Previous studies suggest a better PMD outcome in patients with a comorbid DSM Axis I disorder

39 and in those with a positive perception of their social situation and physician.

44 Outcomes are less favorable in patients who have a personality disorder,

45 experience secondary gain,

39 and in those who are suspected to have a factitious disorder or malingering.

21,35 Age at onset

46 and pending litigation

39 also may influence PMD outcome, but data are conflicting.

21,44,47 In agreement with several previous studies,

2,39,40,43–45,48 we found that PMD prognosis was more favorable in patients with a shorter disease duration. Accordingly, clinicians should aim to lessen the interval between symptom onset and diagnosis, so that counseling and treatment can be implemented as early as possible in the disease course.

PMDs have been associated with depression, anxiety, and personality disorders,

2,21,40,44 but surprisingly little else has been published regarding psychological comorbidities. Literature on conversion disorder in general has found associations with previous trauma, and common psychobiological systems may underlie conversion disorder and posttraumatic dissociative symptoms.

28 In our cohort, one-fifth of patients reported a history of abuse, and half met the cutoff score for PTSD on the PCL. We did not, however, find evidence of significant dissociation on the DES. An earlier study of patients with fixed dystonia, a condition that frequently has a psychogenic basis, also failed to find notable changes on the DES,

42 whereas DES scores are elevated in persons with psychogenic seizures.

49 As psychogenic seizures and PMDs are similar in terms of phenomenology, the lesser degree of dissociation in PMD patients may be related to the more continuous, less episodic nature of their illness. Health locus-of-control refers to the degree of control that patients believe various factors possess over their personal health. Health locus-of-control has prognostic relevance in many illnesses, in that a greater sense of self-efficacy (internal locus-of-control) facilitates effective coping and treatment strategies.

50 For example, a greater belief in personal control over one's illness has been shown to predict a favorable prognosis in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia, two syndromes that often coexist with PMDs.

51,52 Some studies also have found that psychogenic or functional disorders may be associated with a lower internal locus-of-control when compared with healthy subjects.

49 In this study, locus-of-control scores were similar to those of a previous study of patients with organic dystonia

50 and in line with other normative data for patients with other chronic illnesses.

27 We did not find that MHLC scores were of prognostic significance in this sample of PMD patients, but further work in a larger population is warranted.

We recognize limitations of this study, including the small sample size, heterogeneous population, relatively short duration of follow-up, lack of a control population. and high drop-out rate (42% for the PMDRS). We attempted to maximize objectivity by utilizing PMDRS scores as our primary outcome, which were assessed by an independent, blinded, rater. Adequate patient blinding of TENS versus a placebo (sham) device would have been inherently problematic because of the tingling sensation that is generated by the electrical current.

53 Furthermore, although a placebo-controlled study would be preferable, the effect of placebo in PMDs may be more complex than in other neurological disorders.

54 One goal of conducting a placebo-controlled trial is to clarify whether a perceived treatment effect is the result of suggestion versus a physiological effect on the specific disorder being studied. However, the placebo response and other forms of suggestion, such as hypnosis, are themselves routed in a neurobiology. Physicians have long postulated mechanistic similarities between psychogenic disorders and hypnotic states, a view that is now being explored with functional brain imaging and other techniques.

55–58 If the PMDs and suggestion share common neural systems, it is feasible that placebo might correct (perhaps temporarily) the reversible neurophysiologic disturbances that underlie some psychogenic disorders, thereby clouding the conceptual distinction between a placebo and a disease-modifying effect.

When counseling patients regarding the use of TENS (or other possible treatments) for PMDs, we would urge clinicians to discuss the gaps that exist in our current understanding of PMD neurobiology and acknowledge the regrettable fact that no therapies are proven effective in placebo-controlled studies. Despite these limitations, this study confirms that patients with a shorter PMD duration have a more favorable prognosis and that early intervention in the context of a supportive physician–patient relationship is desirable, even when treatment strategies lack a firm evidence-base.