Depression is a prevalent and treatment-responsive illness, yet most people experiencing a major depressive episode go either undetected or inadequately treated (

1,

2 ). For those who do receive antidepressant treatment, which is the most commonly used treatment method in family practice, poor adherence to the treatment plan is common and contributes to inadequate responses and relapse of symptoms (

1,

3 ). The minimum suggested duration of antidepressant treatment for a major depressive episode is eight months, consisting of an eight- to 12-week acute treatment phase followed by a minimum of six months of maintenance therapy (

4 ). However, approximately one in ten patients prescribed an antidepressant does not have the initial prescription filled (

5 ), and among those who do, 30 percent stop taking their medication within a month and 45% to 68% stop treatment altogether by three months (

6,

7,

8,

9 ). Long-term adherence, of at least eight months, is clearly desirable, given that the greatest benefit of antidepressant treatment appears to be the associated reduction in risk of relapse (

10 ).

Effective interventions aimed at improving treatment adherence remain elusive despite extensive efforts (

11,

12 ). However, as noted by Donovan (

13 ), the patient's perspective has not been considered adequately, and several studies have demonstrated that physicians' recommendations often do not match patients' treatment preferences (

14 ). Donovan suggested that involving patients more fully in treatment decisions could lead to improved long-term treatment acceptance. The benefits of this approach, though not necessarily achieved in all investigations, include improved patient knowledge, a sense of feeling informed, satisfaction with the decision-making process, reduced decisional conflict, and adherence with the treatment decision. There is little evidence as yet that supports the contention that including patients in the decision-making process leads to improved clinical outcomes. The benefits of including patients more fully in treatment decisions have been demonstrated for patients with benign prostatic hypertrophy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, and cancer (

15,

16 ). No studies have examined the effect of this approach when making antidepressant treatment decisions for patients with depression, although there are indications that patients with depression would prefer and may benefit from a collaborative decision-making approach regarding their treatment options (

17,

18 ).

The process of involving patients in treatment decisions requires an exchange of information to ensure that both practitioners and patients are making informed contributions. That is, practitioners will need to learn about the patient's illness, treatment experiences, other health problems, treatment preferences, and payment issues, and patients will need to be informed about the various treatment options and will need to be provided with the opportunity to consider this information before indicating their preferences (

19,

20 ). The efficiency of this process can be improved on by knowing in advance what information is important to patients for making treatment decisions. Regarding antidepressant treatment, no studies have identified what factors are most important to patients in choosing a particular agent. This information is essential to facilitating their informed participation in the decision-making process. The purpose of this study was to identify and measure the value of antidepressant treatment selection factors, from the patient's and the practitioner's perspectives, for a patient in primary care with depression for whom the initiation of antidepressant therapy is desired.

Discussion

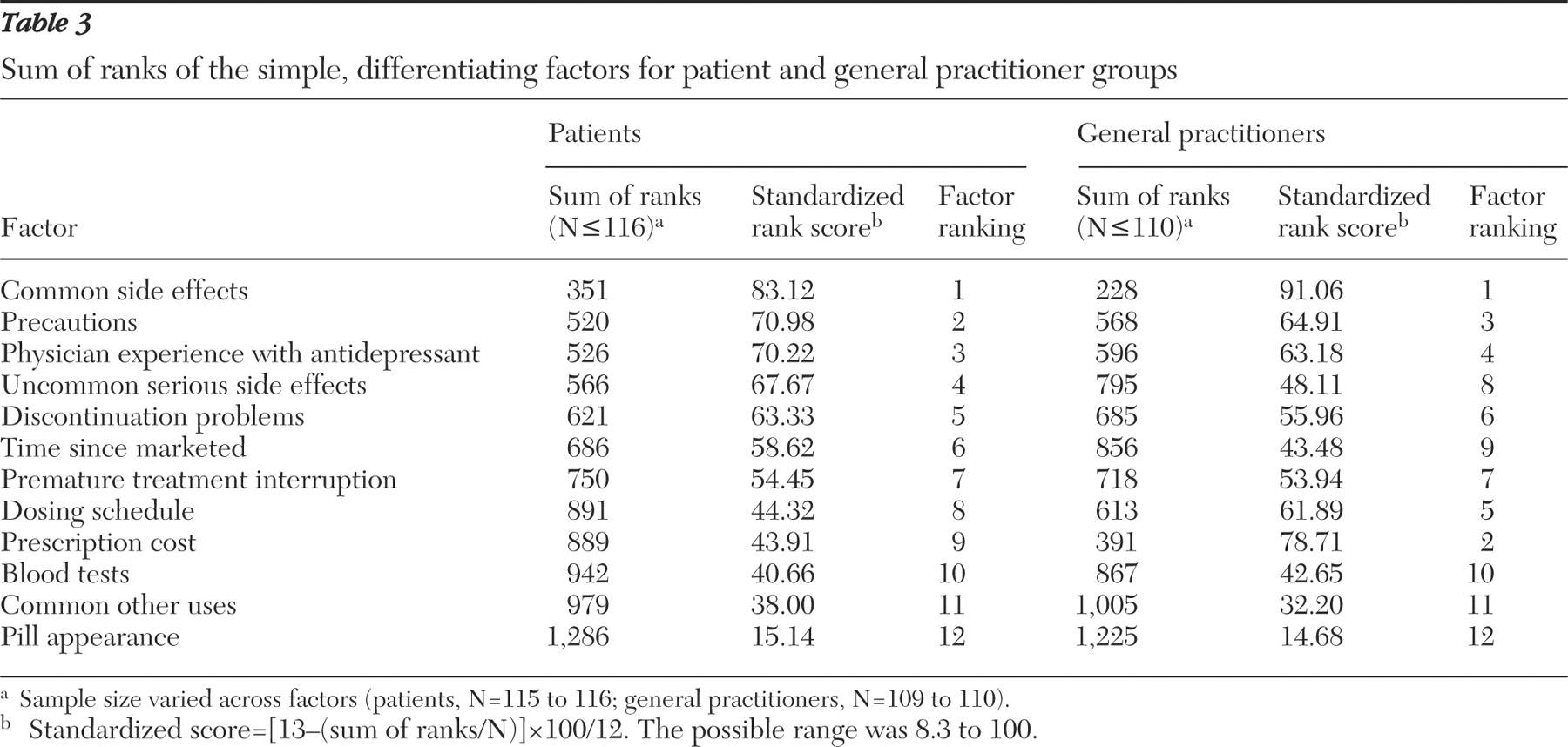

Not all factors identified in the focus groups distinguish one antidepressant from another—for example, the expected duration of treatment or the usual time to onset of subjective benefits. These factors, though important in terms of educating the patient about what to expect from treatment, do not help patients, or practitioners, select among antidepressant agents. Factors that differentiate antidepressants can be divided into two groups, complex and simple. To differentiate among the antidepressants using complex factors—such as those based on interactions between drugs, mechanisms of action, and management of adverse effects—medical training or lengthy details are required. Asking a patient to consider these factors would be impractical. However, by knowing how antidepressants differ in terms of simple, differentiating factors, patients can participate in the antidepressant selection process.

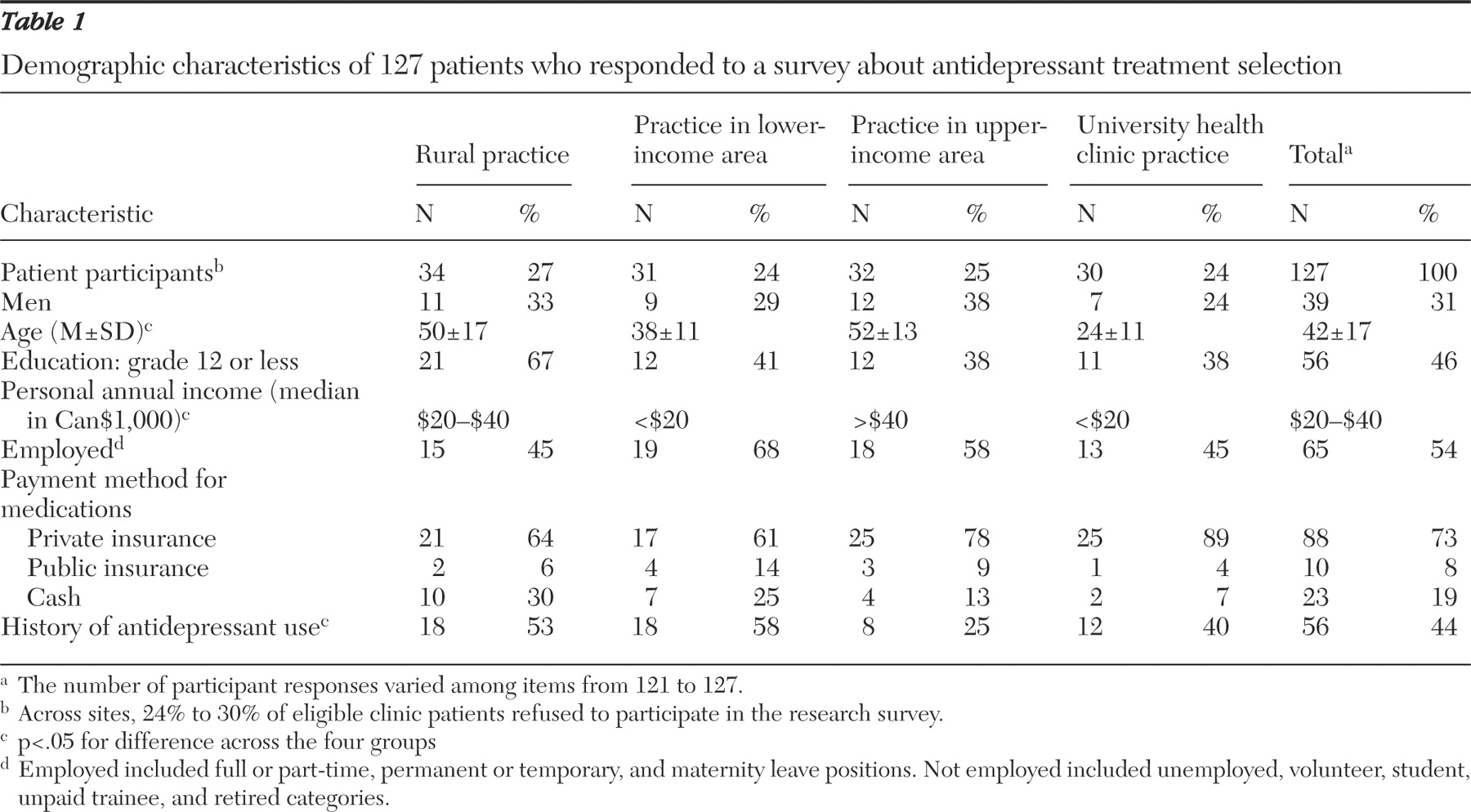

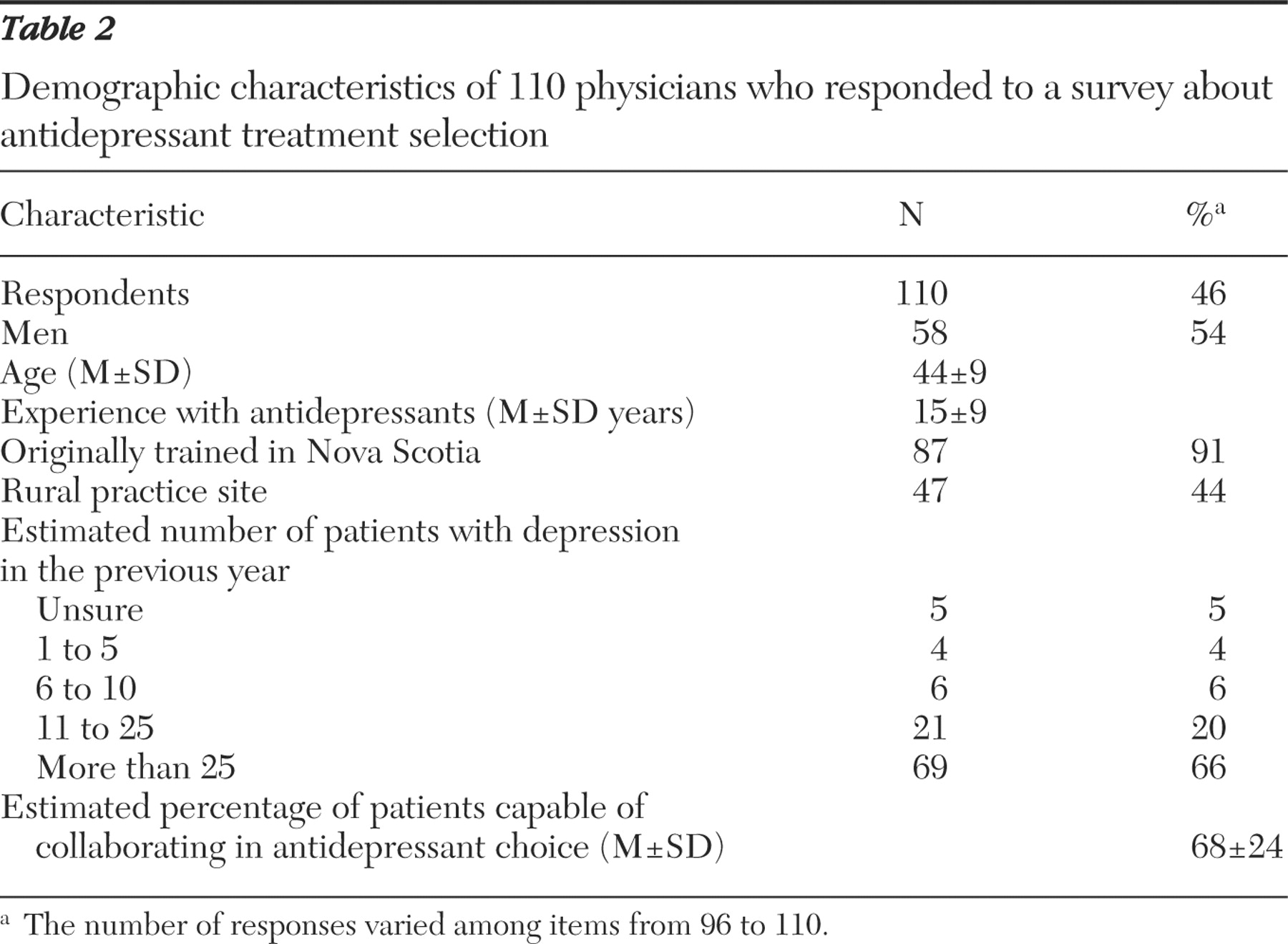

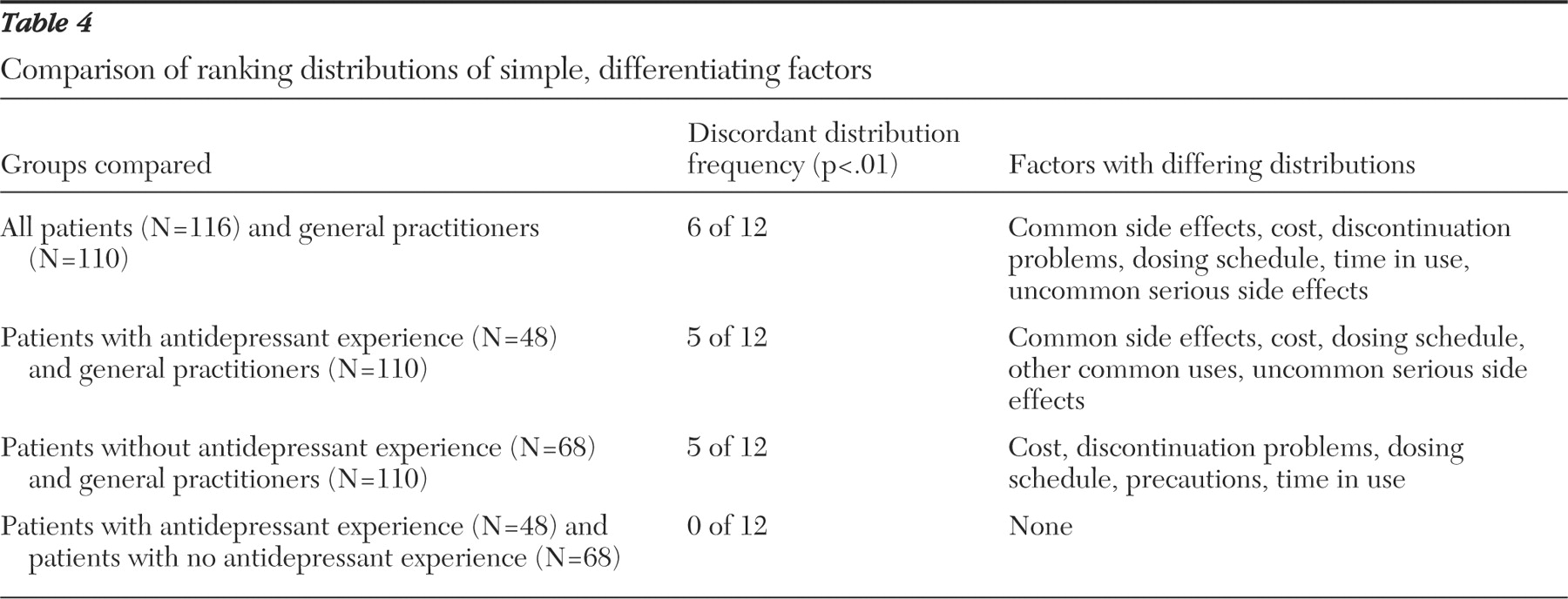

Of the simple, differentiating factors, both patients and general practitioners ranked common side effects as most important. However, when considering the top six ranked factors, the two groups had only intermediate agreement on factor priority. Both groups agreed that common side effects, precautions, physician experience, and problems when discontinuing antidepressant treatment were important factors to consider. However, there was increasing divergence with respect to the importance of dosing schedule, time in use, uncommon serious side effects, and particularly prescription cost.

The most striking difference identified was how prescription cost was valued. Physicians projected cost to be the second most important simple, differentiating factor for a patient to consider in selecting an antidepressant, whereas patients of general practitioners ranked it ninth of 12. Because this finding suggested that this factor is sensitive to prescription payment method, we conducted a subanalysis of patients who paid cash for prescriptions and found cost to be ranked fourth of 12. This finding indicates that practitioners should ask their patients if they have medication insurance (public or private) when choosing an antidepressant. How patients pay for medications in our sample matched well with national statistics (22% paid cash, and 78% had private or public insurance), suggesting that the results may apply elsewhere in Canada (

26 ).

Possibly the most important difference in priorities was found for uncommon serious side effects. The large separation between the two side effect factors implies that general practitioners feel patients should strongly consider common but not uncommon serious side effects when choosing an antidepressant. Patient responses suggested that knowing the uncommon serious side effects is important in the treatment selection process. Others have similarly found that most patients wish to be informed of all possible treatment-related risks (

27 ). The difference in priority level between patients and physicians may in part reflect different perceptions of what is meant by uncommon, or it may relate to the challenges of discussing uncommon or rare serious adverse effects in routine practice. These include the time involved, the possibility of inducing irrational decisions, and the not uncommon difficulty of addressing the uncertain causal link (

28,

29 ). However, despite these issues, practitioners remain ethically bound to inform patients of the potential risks of treatment, even if rare (

30,

31 ). Further work is needed to determine the most effective and constructive ways in which this can be accomplished.

Contrary to what was expected, patient experience with antidepressants did not lead to improved concordance with general practitioners' values. The priorities of patients with and without antidepressant experience were very closely matched. Findings suggest that what was important to patients when receiving their first antidepressant remained important later with growing experience. It also supports the decision to survey an unselected sample of primary care patients.

On the basis of this survey, patients and practitioners, using a shared decision process, should consider how antidepressants compare in terms of risks (common and uncommon side effects, precautions, and discontinuation problems), physician experience (taking care not to unduly influence the decision), prescription cost, and dosing schedule. Providing this information relative to antidepressant choice would satisfy patients' expressed informational needs for differentiating among their treatment options. However, this information alone would not be sufficient for fully informing a patient about antidepressant therapy. Other information identified as important to patients by this survey was treatment effectiveness, the possibility of drug interactions, the time it takes for the benefits of treatment to become noticeable, and how the medication works. These findings are consistent with the observations and recommendations made by Bultman and Svarstad (

20 ). Inclusion of this information in a general, noncomparative format is critical for informing patients about what to expect from treatment regardless of the medication chosen and may in and of itself contribute to improved treatment acceptance (

8,

20 ).

The findings of this research need to be put into context of the overall goal of antidepressant therapy, which is to improve patient outcomes. The overriding assumption is that patient participation in antidepressant decisions will lead to improved acceptance of the antidepressant in the long term. Also, this improvement should, in turn, offer better patient outcomes, such as improved symptom response and quality of life, a greater probability for a timely return to normal functioning, and a reduction in the risk of relapse. However, numerous interventions, such as patient education programs, aiming to improve these outcomes have been tried with disappointing results. What does appear to provide benefit is a collaborative approach that includes enhanced patient education, some form of case management, and application of the shared care model among practitioners (

32,

33 ). It is therefore necessary to test this assumption while also applying the other components of care shown to be predictive of these desirable outcomes.

Although the setting of this study was a single province in Canada, it seems reasonable to assume that patient preferences for antidepressant information would be similar overall in other countries. What may vary somewhat is the value attributed to drug cost depending on patient ability to pay as well as the patient's expectation of financial support.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was completed as Dr. Gardner's master's thesis in Community Health and Epidemiology at Dalhousie University. Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation. The funding agreement ensured the authors' independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. The authors acknowledge the contributions of John Hickey, M.D., Kevin Duplisea, B.Sc.Pharm., Lindsay King, B.Sc.Pharm., Rachelle Couttreau, B.Sc.Pharm., Harold Boudreau, B.Sc.Pharm., Kimi Tiwana, B.Sc.Pharm., and Andrea Murphy, Pharm.D.

The authors report no competing interests.