Long-term implementation intention

Because the CTP was not completed at the time that this ethnographic study was conducted, it was impossible to assess the likelihood of continued use of the standard or modular manualized approach of any of the three evidence-based treatments. However, reports by clinicians in the standard and modular manualized conditions and clinical supervisors revealed three discrete patterns of potential long-term implementation. The first pattern was faithful application of the treatments as specified with all or most of the clients in need of these treatments. One clinician interviewed indicated that she hoped to have at least one of each kind of case so that she would know how to do all of the treatments once the study was over. Another clinician stated that she wanted to learn the protocol for use with a client who was not in the study. Four of the six clinicians who indicated their intention to continue using the treatments with fidelity to the protocols as trained were in the modular manualized treatment condition.

In contrast, some clinicians indicated that they were unlikely to continue using the treatments once the study has ended. For example, one clinician commented that she would "definitely not be doing this were it not for the fact that I agreed to participate in the study." Another clinician expressed dissatisfaction with the techniques of parent management training because it left her little time to devote to other practices, such as play therapy, in which she had more confidence. All four clinicians who indicated that it was their intention to stop using the evidence-based treatments once the study was completed were in the standard manualized treatment condition.

Most clinicians in both conditions, however, seemed likely to adopt a third pattern—selective use of treatment components. Fourteen of the 24 clinicians interviewed reported that they would continue using some of the techniques, but, as described by one of the clinical supervisors, "either they might select one of the protocols and use it or use it for some of their clients but not for the majority of them." One clinician in the standard manualized treatment condition stated, "I would like to use them again but not necessarily in the same order. I like some of these pieces a lot, and some of these not so much." Ten of the 14 clinicians who anticipated selective use after study completion were in the modular manualized condition, and four were in the standard manualized condition; all indicated they would attempt to apply the selected components for specific clients with fidelity as prescribed in the modular manualized version of treatment.

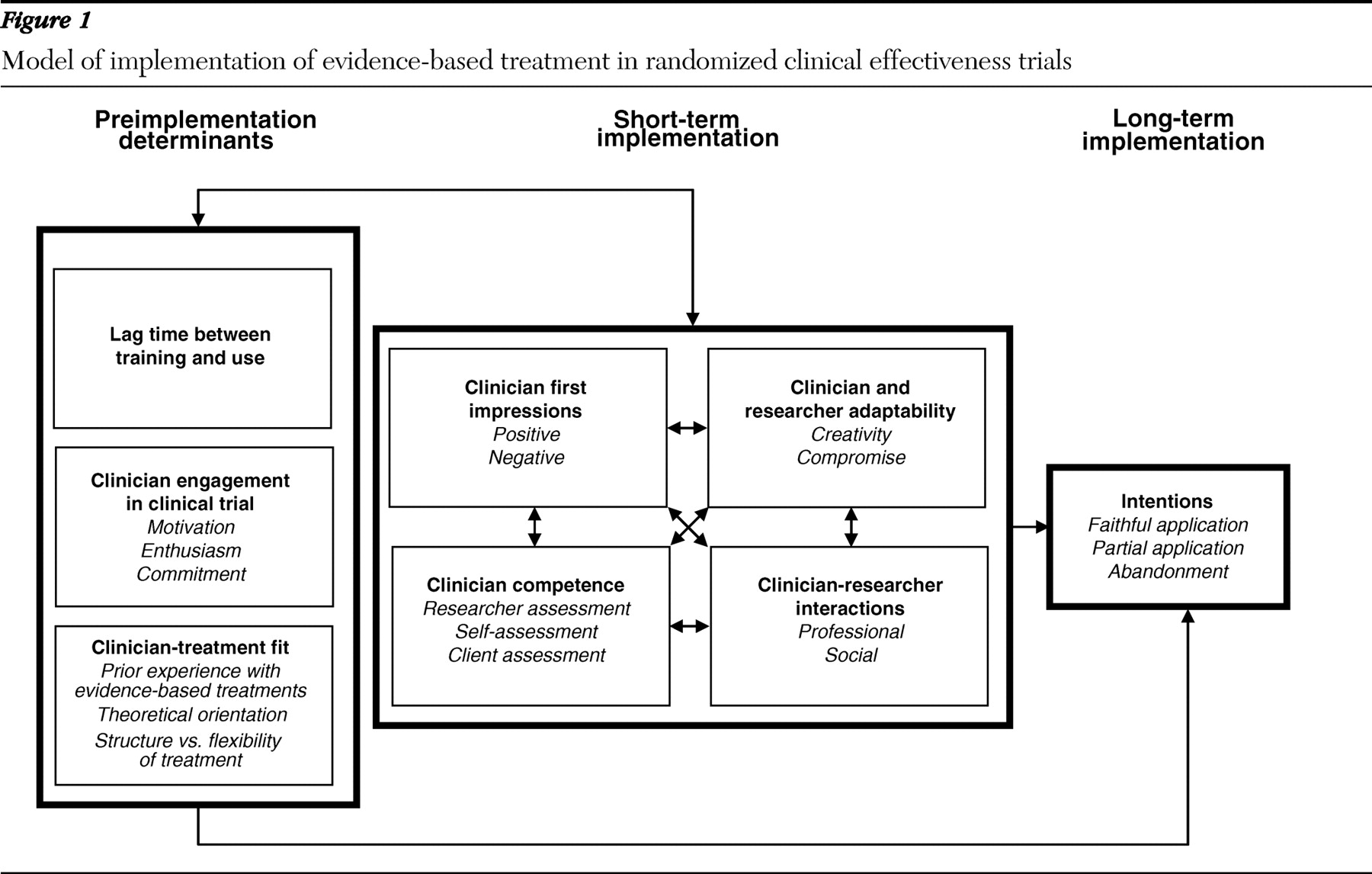

Determinants of implementation

Three primary factors emerged as perceived determinants of evidence-based treatment implementation: lag time between training and use, clinician engagement with the clinical trial, and clinician-treatment fit.

Lag time between training and use. Supervisors cited the lag time between initial training in the treatment protocol and treatment use in practice, as well as the number of practice cases, as primary factors related to clinician intention to continue using the treatments once the project had ended, as well as clinician competence in using the treatments. One supervisor observed, "For the first group [of clinicians trained in Hawaii], there was such a long lag time between when they went through the training and when they picked up cases that they lost a lot of what they had in the training." A few clinicians expressed frustration that using the new skills was delayed by slower-than-expected client recruitment. As the CTP progressed, however, the length of time between training and application was reduced considerably.

Clinician engagement in the clinical trial. The level of engagement of clinicians in the standard and modular manualized treatment conditions was another important determinant of implementation intention. By engagement, clinicians and supervisors meant the motivation and enthusiasm for and commitment to participating in the implementation of the evidence-based treatments within the controlled and highly regulated process specified by the design of a randomized clinical trial. All clinicians had provided informed consent to participate in the study; however, some were more excited than others about participating, citing factors such as the opportunity to learn new techniques that could increase their effectiveness as clinicians as well as their marketability and the opportunity to contribute to the field by participating in a research project. One supervisor described this group of clinicians as follows: "They read their manuals every week before sessions. They get it in terms of getting that there is a protocol for them to follow, where they can do it without being coached."

Clinicians who were less enthusiastic about participating in the CTP were identified by research supervisors as being more difficult to supervise and more likely to express the intention to discontinue treatment use upon project completion. During training, clinicians randomly assigned to the standard manualized condition were less enthusiastic about participating than clinicians assigned to the modular manualized condition, citing fears that it would be too inconvenient to use and not acceptable to clients and would limit the ability of the clinician to exercise creativity and control over the treatment process.

Perhaps the best indication of engagement, based on statements provided by clinicians and clinical supervisors during interviews, was the perception that clinicians remained committed to adopting the treatments despite the challenges involved. This commitment was evident even among clinicians who held negative opinions of the treatments, and it seemed to be independent of assignment to treatment condition. As one clinician stated, "I am going to do their study, whether it feels good or not. This is what I signed up for, and I'm going to do it!"

Clinician-treatment fit. A third determinant of intended long-term use of the evidence-based treatments was the match between certain clinician and treatment attributes. For example, clinicians randomly assigned to the standard manualized treatment condition who preferred or needed structure in working with clients or who had previous experience in using structured practices were more likely than clinicians without these needs or preferences to have positive impressions and experiences and exhibit competence in applying these treatments with clients. Clinicians whose clinical experiences and theoretical orientation called for a more flexible approach to working with clients were better suited to the modular manualized condition.

Among the factors that influenced this fit was the clinician's previous clinical experience. For instance, some clinicians expressed difficulty adopting the behavioral techniques of parent training because they were not accustomed to working with parents. One supervisor noted that clinicians who were struggling with the standard manualized treatment protocol were accustomed to more unstructured practices, whereas those who were successful had "some components of their usual approach to treatment that were a little bit more structured." Two clinicians reported that they had never before used a manual to treat a client.

Another factor related to the fit between clinician and evidence-based treatment was the clinician's theoretical orientation, as exemplified in this comment from one supervisor about one of the clinicians in the standard manualized condition: "Having a plan was a bad thing because it was supposed to come and be derived from the child. It was really in the opposite direction. And there was direct conflict between what we had been talking about and what she had been trained in." Other clinicians reported that they did not believe in timeout as specified in the behavioral parent training protocols. Although these clinicians used the techniques as instructed, it was unclear whether they would continue to use them once the CTP was finished.

Short-term implementation

Four additional themes emerged from our analysis of possible determinants of long-term intention to implement the evidence-based treatments, and these appeared to represent components of the initial or first steps of implementation—after training and during the first six months of treatment use. These four themes were clinicians' first impressions (positive and negative) of features of the treatments, clinician competence in treatment application, clinician and researcher adaptability, and clinician-researcher interactions.

Clinician first impressions. This theme represented a cognitive dimension of evidence-based treatment use that included positive and negative attitudes and beliefs and expectancies informed by preimplementation factors and by initial experiences with treatment use. Many clinicians made positive comments about features of the treatments, especially the depression and anxiety programs, noting that they represented something new in terms of clinical practice; provided a more structured approach to things that the clinicians were doing already, which was especially helpful for clinicians with limited clinical experience; and were somewhat familiar. One clinician interviewed during a training workshop expressed satisfaction that the treatments were based on clinical experience. Other clinicians came to accept the treatments after beginning to use them. Several clinicians interviewed after training expressed surprise at how well they had been able to use the manuals or how well parents had been engaged in treatment. In general, clinicians who were perceived by supervisors to be using a treatment well were positive about it.

However, many clinicians also had negative impressions, particularly of the behavioral training for parents. The clinicians had several practical concerns about this treatment. One was having to "translate" the treatment for parents to make it sound less scientific. Another was having to anticipate that the child might refuse parental instructions and that the parent would feel it was not worth fighting for. Clinicians also had concerns that families would be unable to handle the sophistication of a point system designed to reinforce positive behavior. The clinicians were concerned that they had insufficient time to teach a skill in a session and that they lacked clinical resources to make it work. Clinicians also expressed more philosophical concerns. Some were concerned that actual cases would be more complex than those described in the training materials. Some were ambivalent about using protocols that they perceived to be too structured, rigid, and inflexible. For some clinicians, these impressions were reinforced by initial experiences in using the treatments. They reported that the treatment was hard to do, both for the client and for themselves.

Clinical competence. A behavioral dimension of the first steps of implementation was the clinician's skill in using the evidence-based treatment. Supervisors reported considerable variability in clinician competence. For instance, some clinicians failed to complete homework assignments or prepare for sessions as instructed. Some clinicians were quick to learn the skills and apply them in practice cases and with actual clients, whereas other clinicians were perceived to be "just not getting it." This assessment was made by supervisors, clients, and the clinicians themselves. One clinician, for instance, claimed that she had been "fired" by a parent of one of her clients because of dissatisfaction with the lack of treatment progress.

Clinician and researcher adaptability. The degree to which both clinicians and researchers exhibited adaptability in assuming their respective roles within the CTP was another important component of short-term use of the evidence-based treatments and a determinant of intended long-term use. One indicator of this adaptability among clinicians was the extent to which they took initiative and exercised creativity in applying the material and integrating it with their own theoretical orientation and previous training. According to a supervisor, one clinician "used these techniques a bit more flexibly than we would have wanted. But she pulled it off really well, and so I kind of … felt more comfortable [in the therapist's] straying from maybe what would have been ideal for the study." Another clinician who believed that nutrition is fundamental to mental health added a component about nutrition in the behavioral parent training. Other clinicians, as one supervisor put it, "pretty much do what they need to do to stay on track."

A second indicator of adaptability was the extent to which a clinician was willing to compromise by abandoning, at least in part, usual patterns of treatment and theoretical orientation toward treatment. For instance, one clinician commented, "I don't want to take on more cases because they are more work than I had realized." However, he was prevailed upon to do so by his research supervisor. Other clinicians agreed to instruct parents in using timeout techniques as specified by the behavioral parent training manual (

30 ), even though they personally did not believe in timeout.

The same two indicators of creativity and compromise on the part of the researchers also were perceived to be a critical component of short-term use of the treatments and a determinant of intentions for long-term use. To varying degrees, project investigators and supervisors worked to create positive first impressions of both standard and modular manualized treatment approaches and exercised creativity in working with clinicians to improve competence in treatment use. Activities that were undertaken to find common ground with the clinicians included identifying the consistency between the treatments and a clinician's own theoretical orientation, exhibiting a willingness to understand that orientation and fit the treatments within its framework, incorporating clinician suggestions in treatment use, accommodating clinician priorities, building a common language or using the clinician's language to more effectively communicate with the clinician, seeking out clinician strengths and motivations, and being deferential to certain clinicians and directive with others. Not every supervisor employed these strategies, and not every strategy was employed with every clinician. However, both researchers and clinicians who reported using these strategies suggested that they played an important role in improving clinician performance in treatment use.

Similarly, although supervisors were charged with helping clinicians use the treatments as they had been trained to do, they were reluctant to push clinicians too far for fear of having them withdraw from the study, thereby jeopardizing the study's integrity and power to detect a statistical difference between the standard and modular manualized approaches to treatment and between the two approaches and usual care. Project investigators thus devoted considerable time and energy looking for the "right balance" between the treatments as designed and as preferred by the clinicians. In doing so they often exerted a degree of compromise in working with clinicians. For instance, when looking for reassurance that they might not be able to cover everything in a session as prescribed by the manual because of a lack of time, clinicians were told by investigators, "This is fine as long as you get to an understanding of the skill."

Clinician-researcher interactions. Of all the positive features of the treatments, the one cited most frequently by clinicians and supervisors alike was the supervision that came with project participation. Clinicians who had begun working with supervisors on actual cases commented on how much they enjoyed being supervised and how much it helped to improve their clinical skills in general. According to one supervisor, "All the clinicians who were participating [at one clinic] were saying really positive things. They like getting paid for getting an hour of supervision on a case. To have that in their schedule … they see as a luxury." A clinician reported that the time spent interacting with a research supervisor during her weekly sessions was "the best thing about the project."

CTP investigators and supervisors also exercised creativity and compromise in engaging in non-work-related social interactions with clinicians. They planned and participated in social activities with clinicians, such as dinners to honor clinicians for their involvement in the project or potluck picnics and lunches, and they engaged in non-project-related discussions and activities at clinicians' request, including providing advice to clinicians who sought their help about how to handle problems at work, take care of ailing parents, or cope with children going off to college or who had questions about career opportunities or about cases unrelated to the study. However, one supervisor reported that such interactions required considerable time and energy on her part, and not all supervisors or clinicians were willing or able to engage in such interactions.