Irregular patterns of service use, including attrition from care, are common among individuals with schizophrenia, as they are among individuals with other chronic conditions (

1,

2 ). Both the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study and the National Comorbidity Survey found that approximately half of individuals with schizophrenia had received no mental health services in the preceding 12 months (

3,

4 ). Among those who received outpatient care for schizophrenia, some 25%–30% dropped out of care within a 12-month period (

5,

6,

7,

8,

9 ). Irregular service use is associated with less favorable outcomes of care for schizophrenia, including greater symptom severity and rehospitalization (

10,

11,

12,

13,

14 ). These outcomes are extremely expensive in both human and financial terms.

Identification of personal characteristics associated with irregular service use may help providers predict which consumers are likely to sustain involvement in care. However, if we are to improve rates of sustained involvement in care, we need to emphasize identification of the modifiable characteristics associated with patterns of utilization. We recently conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with individuals with schizophrenia to elicit their perspectives on crucial barriers to and facilitators of sustained involvement in care. Participants reported that support from family members and friends was a crucial contributor to sustained involvement, especially in rural areas where family and friends often helped with transportation. They also reported that substance use or abuse was a common barrier to remaining in care over time. For the study presented here, we analyzed service utilization data to determine whether and how much these two modifiable factors (family support and substance abuse) influenced patterns of care for schizophrenia.

Results

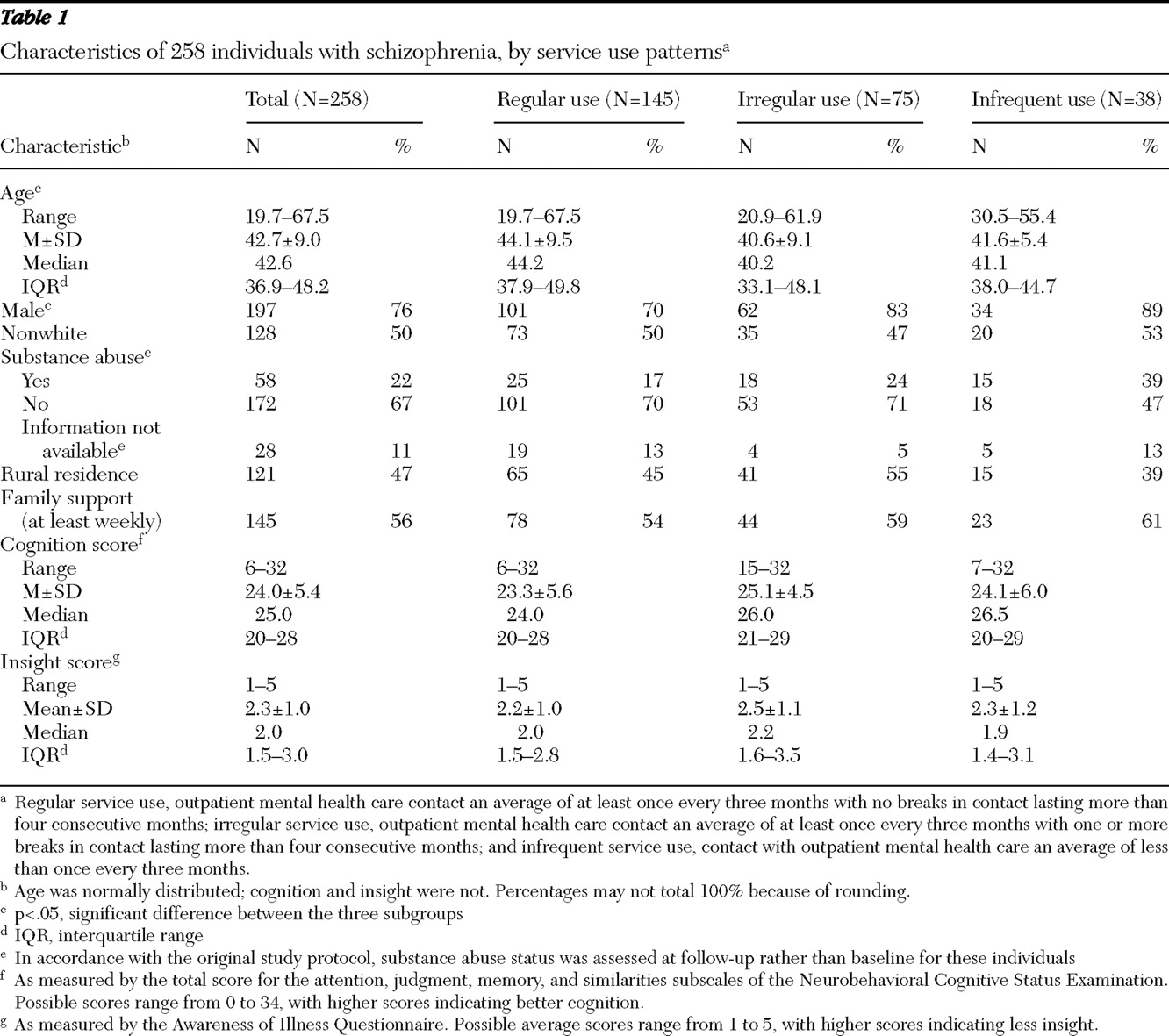

Sample characteristics are summarized in

Table 1, overall and by service use pattern. The overall sample was predominantly male (76%), middle-aged, and approximately evenly divided by ethnicity (130 sample members, or 50% were white, and 128 sample members, or 50%, were nonwhite). Consistent with the population of Central Arkansas in the 1990s, all but two of the nonwhite sample members were African American (N=126, or 49%); one of the remaining two individuals was Hispanic, the other was from "other" race or ethnicity. Substantial proportions of sample members met criteria for a current substance use disorder (22%), were rural residents (47%), and were known to have had at least weekly family support (56%). A majority of sample members used mental health services regularly (145 consumers, or 56%). The three subgroups defined by pattern of service use differed significantly in current substance abuse status (

χ 2 =12.19, df=4, p=.016), age (F=4.18, df=2 and 255 p=.016), and gender (

χ 2 =8.88, df=2, p=.012). Regular service users were more likely to be female and were slightly older than irregular or infrequent service users. Substance abuse was least prevalent among regular service users and most prevalent among infrequent service users. The subgroups did not differ significantly in ethnicity, residence, family support, cognitive functioning, or insight.

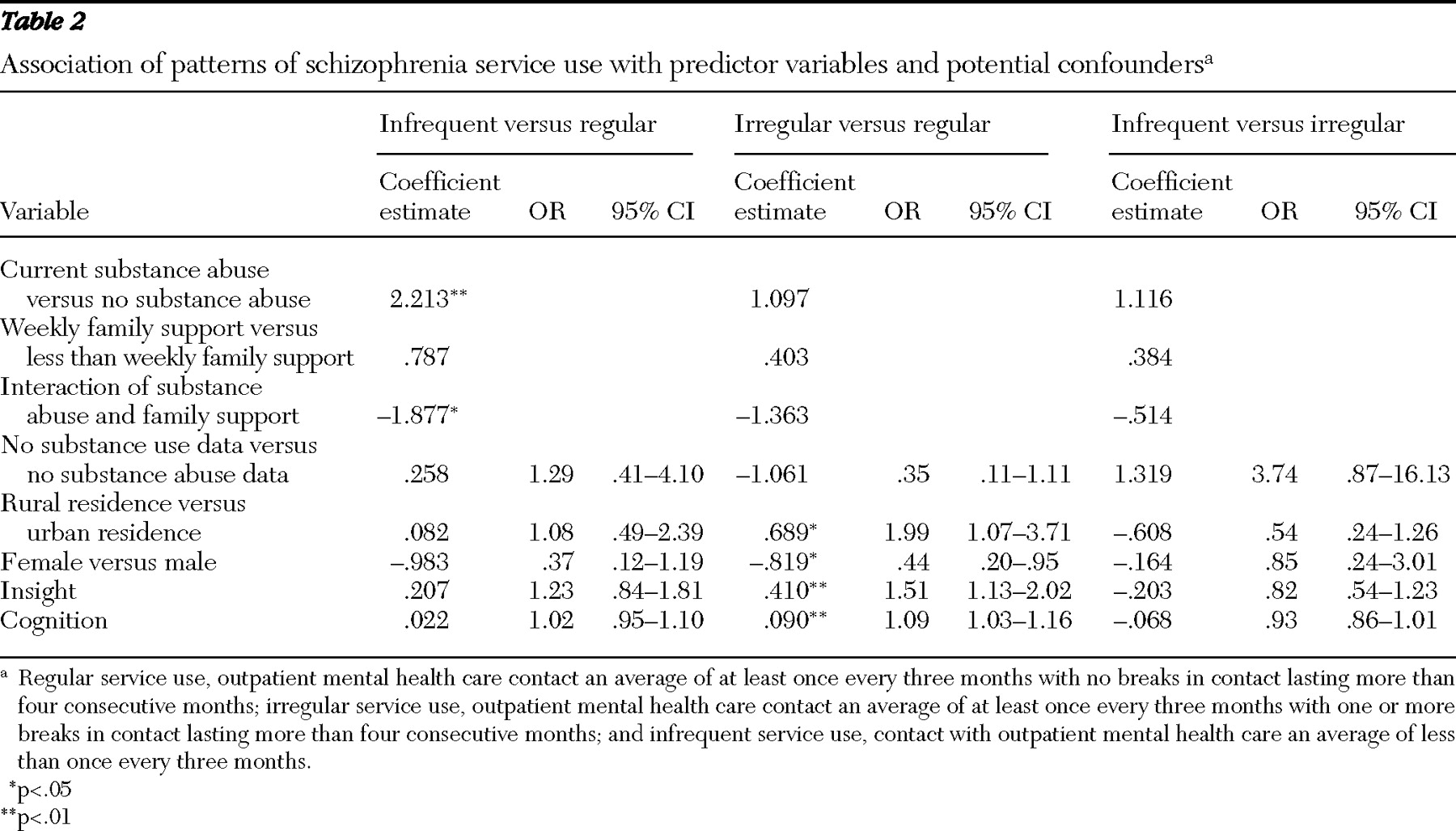

We used polychotomous logistic regression to first regress pattern of service use on the predictor variables of interest (substance abuse status, family support, and rural residence), adjusting for clinical predisposing factors (insight and cognitive functioning). Substance abuse status, cognitive functioning, and insight were significantly associated with the pattern of service use (p<.05). Guided by qualitative interview findings, we then assessed the influence of potential interactions between substance abuse status and family support and between substance abuse status and residence, separately and together. The interaction term for substance abuse status and family support was the only one that was statistically significant and substantially improved the model fit (

26 ). Finally, we added standard demographic predisposing factors, age, gender, and ethnicity (white or nonwhite), to the model to assess their potential confounding effects. Gender was significantly associated with utilization pattern and added to model fit. Ethnicity and age did not contribute to model fit and were not included in the final regression model.

The final model was significant overall (likelihood ratio

χ 2 =43.06, df=16, p=.003). The interaction between substance abuse status and family support approached significance in the overall model (Wald

χ 2 =5.93, df=2, p=.052) and was statistically significant in the comparison between individuals with infrequent versus regular patterns of service use (Wald

χ 2 =4.86, df=1, p=.027). As shown in

Table 2, consumers with a pattern of infrequent outpatient contact were also more likely than those with a pattern of regular contact to meet criteria for current substance abuse (Wald

χ 2 =10.06, df=1, p=.002), even after adjustment for the interaction of substance abuse status and family support. Consumers with a pattern of irregular outpatient contact were significantly more likely than those with a regular pattern of contact to be rural residents (Wald

χ 2 =4.73, df=1, p=.030), to be male (Wald

χ 2 =4.38, df=1, p=.036), and to have better cognitive functioning (Wald

χ 2 =8.28, df=1, p=.004) but poorer insight (Wald

χ 2 =7.64, df=1, p=.006). The interaction between substance abuse status and family support approached significance for this comparison (p=.073). None of the differences between consumers with patterns of irregular or infrequent service use reached statistical significance.

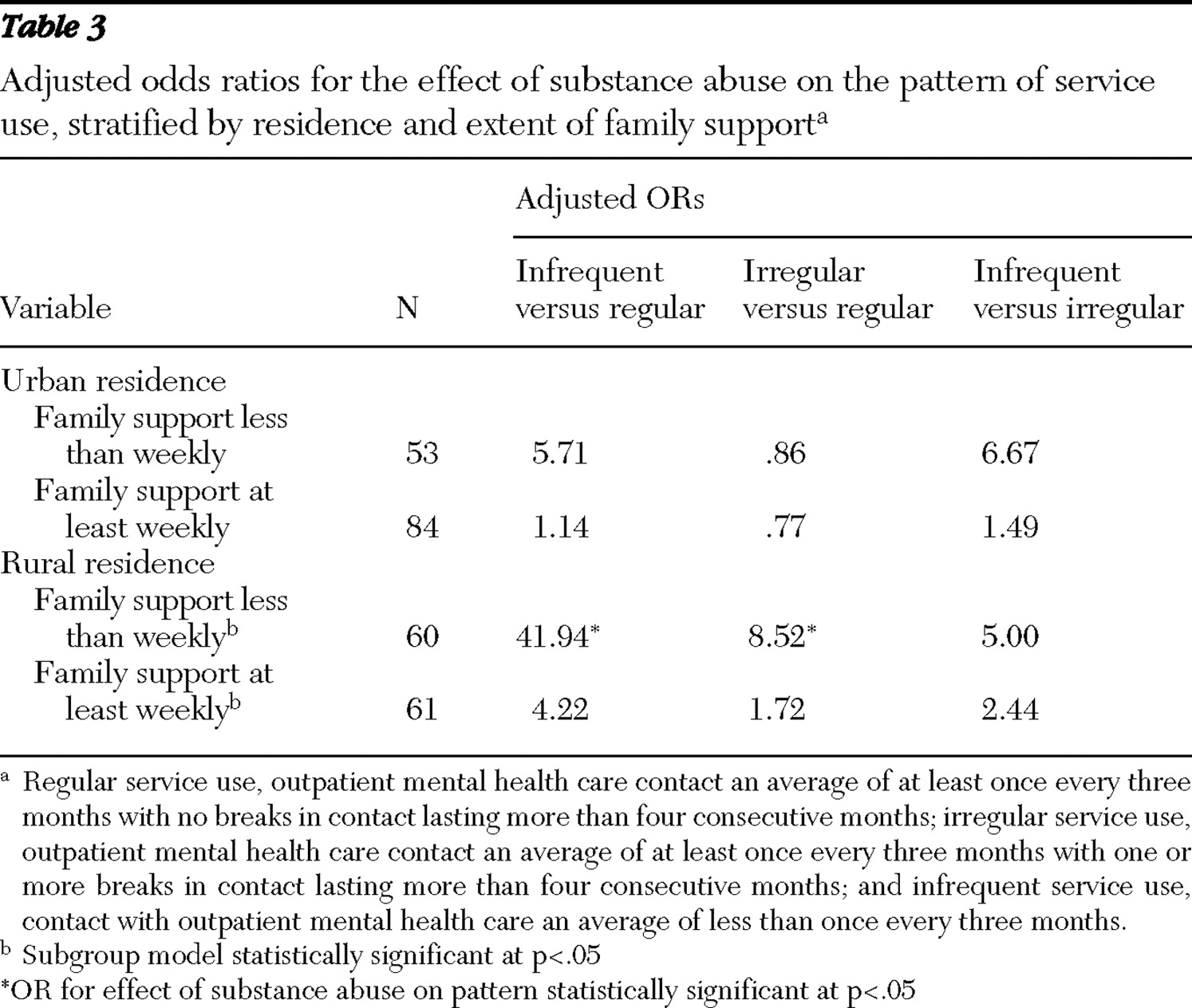

The statistical information in

Table 2 cannot provide a clear picture of the direction or consistency of the substance abuse-family support interaction effect. To be able to describe the ways in which family support modified the effect of substance abuse status on pattern of service use and to determine whether the effect varied by residence, as suggested in our qualitative interviews, we repeated the logistic regression analysis stratified by support and residence. Odds ratios for the association of substance abuse status with utilization pattern, stratified by family support and rural or urban residence, are shown in

Table 3 . Consistent with the results of the full-sample analysis, after adjustment for gender, cognitive functioning, and insight, substance abuse generally increased the likelihood of one of the less desirable patterns of care, regardless of residence or family support. However, the magnitude of the impact of substance abuse on utilization patterns was substantially lower among individuals known to have at least weekly family support, especially in rural areas. Because each of the analytic subgroups includes about a quarter (N=53–84) of the full sample, these exploratory subgroup analyses have considerably less power than the full-group analysis. With the smaller sample sizes, only the subgroup models for rural residents achieved statistical significance. Nonetheless, we consider it useful to show the results of these exploratory subgroup analyses because they most clearly illustrate the way family support and residence modify the association between substance abuse status and patterns of service use.

Discussion

In our sample of 258 individuals with schizophrenia, after adjustment for insight, cognitive functioning, and gender, comorbid substance abuse and the interaction between substance abuse and family support were significantly associated with patterns of service use. Comorbid substance abuse predicted less desirable utilization patterns. Inspection of stratified analyses indicated that weekly family support substantially reduced the adverse impact of substance abuse on consumers' patterns of service use, especially for consumers living in rural areas.

These findings reinforce the picture painted in the qualitative interviews we conducted previously with a small subsample of study participants. They are also generally consistent with the relatively small body of literature on patterns of care for individuals with schizophrenia and the much larger body of literature on predictors of antipsychotic medication adherence in this population. Comorbid substance abuse is a robust predictor of treatment attrition and medication nonadherence (

2 ). Family support and involvement have also been associated with more sustained involvement in care and medication adherence (

27,

28,

29,

30 ). To our knowledge, however, our finding that family support can offset some of the negative impact of substance abuse on sustained involvement in care has not been reported previously.

The study presented here has limitations. First, the relatively small sample size, especially for the group of infrequent service users, limited the power of multivariable models. Second, neither choosing to have a family member participate in the study nor being in contact with family was a criterion for consumer eligibility in either of the original studies. As a result, our measure of family support was based on information from family members who participated in the study. Consumers for whom we do not have data on family support were classified as "not known to have at least weekly family support." Some of those individuals may have had family support that we did not capture. Further, we did not ask about every possible type of family support. Individuals receiving other types of support only may also be misclassified. However, such misclassification would be expected to artificially decrease the magnitude of differences between groups rather than to exaggerate it. Third, because there is no consensus on the optimal frequency with which individuals with schizophrenia should be in contact with mental health service providers, any categorization of utilization patterns is inevitably arbitrary and open to debate. We selected a relatively lenient definition of "regular use" that reflected the least stringent visit interval commonly applied in our outpatient recruitment settings at the time of the study.

Our secondary data analyses cannot further elucidate the ways in which family support may at least partially offset the influence of substance abuse on service use patterns, nor can they identify the individuals for whom it does so. Data from the qualitative interviews that sparked these analyses suggest some mechanisms. Respondents with schizophrenia reported that family members provided transportation, reminded them of appointments, took them to care when they experienced an exacerbation of symptoms, and provided moral support and a feeling of worth. In their own words: "My nephew always reminds me [to keep my appointments] …. [I] ride the bus or my nephew takes me." "My oldest sister has power of attorney…. and Mother is my payee to make sure I get my Social Security." "My mother tells me I should stay in there [treatment] because it's good for me. My daughter tells me too." "Some of the things that helped [me stay in care] … family support, my wife and all, and my mother and brothers and sisters, family support. They supported me." "They [family] encourage me [to stay in treatment]." "Well, by having family … they give me a crutch, you know."

Further, in a longitudinal study of individuals with dual diagnoses of substance abuse and a mental disorder—primarily schizophrenia (54%) or schizoaffective disorder (23%)—Clark (

31 ) found that direct family support (economic or instrumental) was associated with greater reductions in substance use over time. Importantly, those analyses, which adjusted for baseline consumer involvement in substance abuse treatment, provide strong suggestive evidence that family support is not solely determined by whether the consumer is in treatment for substance abuse or how well the consumer is doing in that treatment (

31 ).

In many instances, the extent and nature of family support is a modifiable phenomenon. If the interaction we observed between family support and substance abuse is confirmed in other populations, it has potentially important implications. Comorbid substance abuse is prevalent among individuals with schizophrenia. At the same time, a high proportion of these individuals remain in touch with their families, and many live with family members (

32,

33 ). Dixon and colleagues (

33 ) found that inpatients with dual diagnoses of severe mental illness and substance abuse reported a greater desire for family treatment than did inpatients diagnosed as having severe mental illness alone. In this context, our findings provide strong backing for efforts to increase the involvement of family members who provide informal care in the treatment process as well as to increase the support available to them. These efforts are crucial as the field increasingly transforms the "mental health treatment process" into a strengths-based "recovery process" (

34,

35,

36 ) and are especially crucial for individuals with dual diagnoses who live in rural areas. The availability of evidence-based professional and lay programs for families as well as support groups for family members should facilitate increasing or reinforcing family involvement.

Although this is an intuitively appealing conclusion, its implementation faces significant challenges. Despite the empirical evidence of the importance of families in care of individuals with schizophrenia (

37,

38,

39,

40 ), few families have contact with the mental health care treatment team (

40,

41,

42,

43,

44 ). The old ideas that contact with family impedes progress or is legally prohibited endure among clinicians (

45 ). In addition, few facilities offer services for families, and those that do often find it difficult to engage family members of persons with schizophrenia (

40 ). This may reflect, in part, families' struggle to handle the day-to-day burden of caregiving and instrumental support for their relative with schizophrenia. Additional information is needed on the mechanisms by which family support ameliorates the adverse impact of substance abuse on patterns of service use and, perhaps, on other aspects of consumers' lives. In addition, creative strategies will be needed, especially for rural areas, to address challenges to increasing the engagement of families in treatment to the level desired by their affected relative.