Knowledge about the characteristics of patients using psychiatric emergency services is important to better understand their clinical needs and improve service delivery in this setting. HIV-positive patients face multiple challenges in coping with their illness, often needing expert emergent medical and psychiatric care. In the general adult population of the United States, the prevalence of HIV infection has been estimated to be between 1.0 and 1.2 million (

1 ). Not surprisingly, higher prevalence rates have been found in various medical settings. Studies determining the prevalence of HIV infection and describing the characteristics of HIV-positive patients have been completed in inpatient psychiatry and medicine wards, outpatient psychiatry clinics, and general emergency departments. However, no estimates have been published to date about the prevalence or the clinical and demographic characteristics of HIV-positive patients seen in psychiatric emergency departments. With this analysis, we sought to fill this void in the literature, using a combination of clinical quality assurance and administrative data of a consecutive series of 58,301 patients. Some patients visit the psychiatric emergency department repeatedly. Thus to more accurately present the prevalence of HIV infection among patients treated at the psychiatric emergency department, we calculated prevalence as well as the clinical and demographic characteristics on a per-visit basis.

Methods

The study was conducted with data collected at Harborview Medical Center's psychiatric emergency service, which serves the city of Seattle and surrounding areas. It is staffed 24 hours a day by attending board-certified or board-eligible psychiatrists, psychiatric residents, nurse practitioners, nurses, and social workers who receive ongoing training in completion of standardized assessment forms through quarterly staff meetings that strive to increase interrater reliability. Data have been collected at this facility since July 1998.

This retrospective study used data abstracted from the quality assurance database for the psychiatric emergency services at Harborview Medical Center. Between July 1, 1998, and November 8, 2007, a total of 67,989 patients, including 33,019 unique patients, were treated. Missing data for demographic characteristics and psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses reduced the analysis sample to 58,301 visits and 28,817 unique patients. We obtained data from all of these visits. Permission to use the data for analysis and publication was granted by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division.

At each visit, clinicians completed a previously validated assessment form that ascertains demographic information and ratings of presenting psychiatric symptoms and provides clinician-rated

DSM-IV diagnoses (

2 ). The demographic information included gender, age, race, and residential status. The patients' psychiatric symptoms were rated on a scale of 0–6, which includes behaviorally anchored sets of descriptors, with 0 indicating a lack of symptoms and higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. Possible symptoms included psychosis, depressed mood, anxious mood, suicidality, homicidality, hostility, and uncooperativeness. Axes I and II diagnoses were derived from the emergency department visit note. Possible diagnoses consisted of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, dementia, adjustment disorder, substance use disorder, borderline personality disorder, personality disorder, mood disorder and anxiety (recorded together in the database), and other disorders. Functional ratings included role functioning, outpatient treatment involvement, alcohol- or drug-related problems, and lack of a social support system. HIV infection information was derived from hospital records.

Prevalence is commonly calculated at the patient level. In contrast, we estimated the prevalence of HIV infection at the visit level. There are two main reasons for our approach. One, our study aimed to better understand the characteristics of psychiatric emergency service utilizers. Two, certain individuals were more like to use psychiatric emergency services repeatedly. Thus, if we estimated prevalence at the patient level, we would not have accounted for the characteristics of frequent psychiatric emergency service users. In addition, with longitudinal data, there is no clear method for accounting for changes in a patient's HIV status over time, if prevalence is estimated at the patient level.

We conducted chi square analyses to examine differences by HIV status for all psychiatric diagnoses and symptoms and for demographic variables. Because of the large number of statistical tests, we applied a Bonferroni correction to the alpha level, resulting in setting the p value for significance at <.003. To identify independently significant variables, we estimated a series of logistic regressions with and without adjustments for gender, race, and age. In the regression analyses, psychiatric diagnoses and psychiatric symptoms were the predictor variables and HIV was the criterion variable. Because our data included multiple observations for some patients, we estimated logistic regressions and adjusted for correlated errors.

Results

Of 28,817 patients, 553 (1.9%) were known to be HIV positive at the time of the psychiatric emergency department visit. A similar proportion of visits to the psychiatric emergency department were by HIV-positive patients (1,178 of 58,301 visits; 2%).

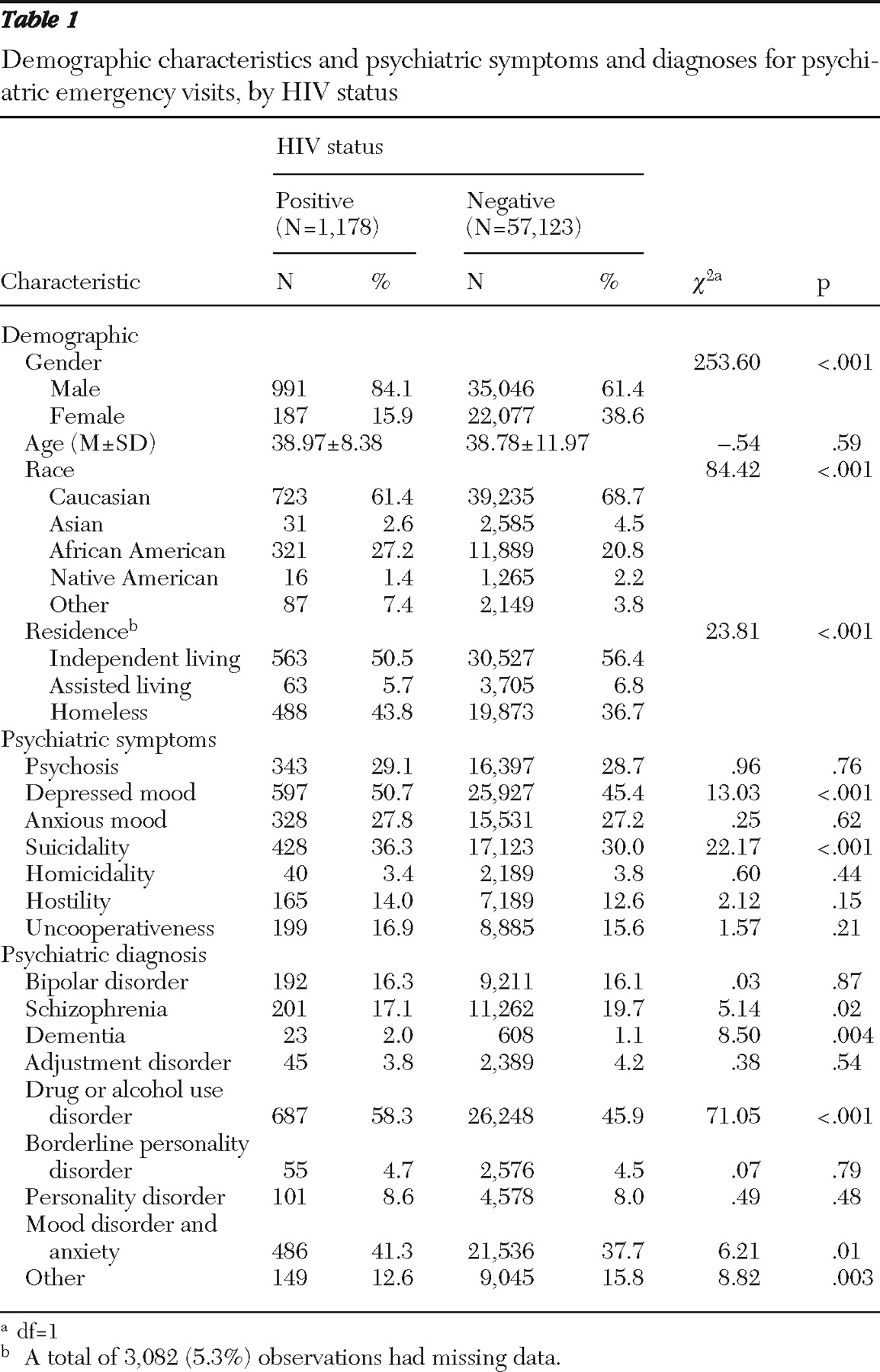

Table 1 lists characteristics of the sample by HIV status. Compared with visits from HIV-negative patients, visits from HIV-positive patients were more likely to be by males (odds ratio [OR]=3.34, 95% confidence interval [CI]=2.49–4.47), African Americans (OR=1.47, CI=1.10–1.95), or in the "other" race category (race other than African American, Asian, Caucasian, or Native American; OR=2.20, CI=1.41–3.44); and homeless (OR=1.33, CI=1.08–1.64). Results from logistic regressions are presented in

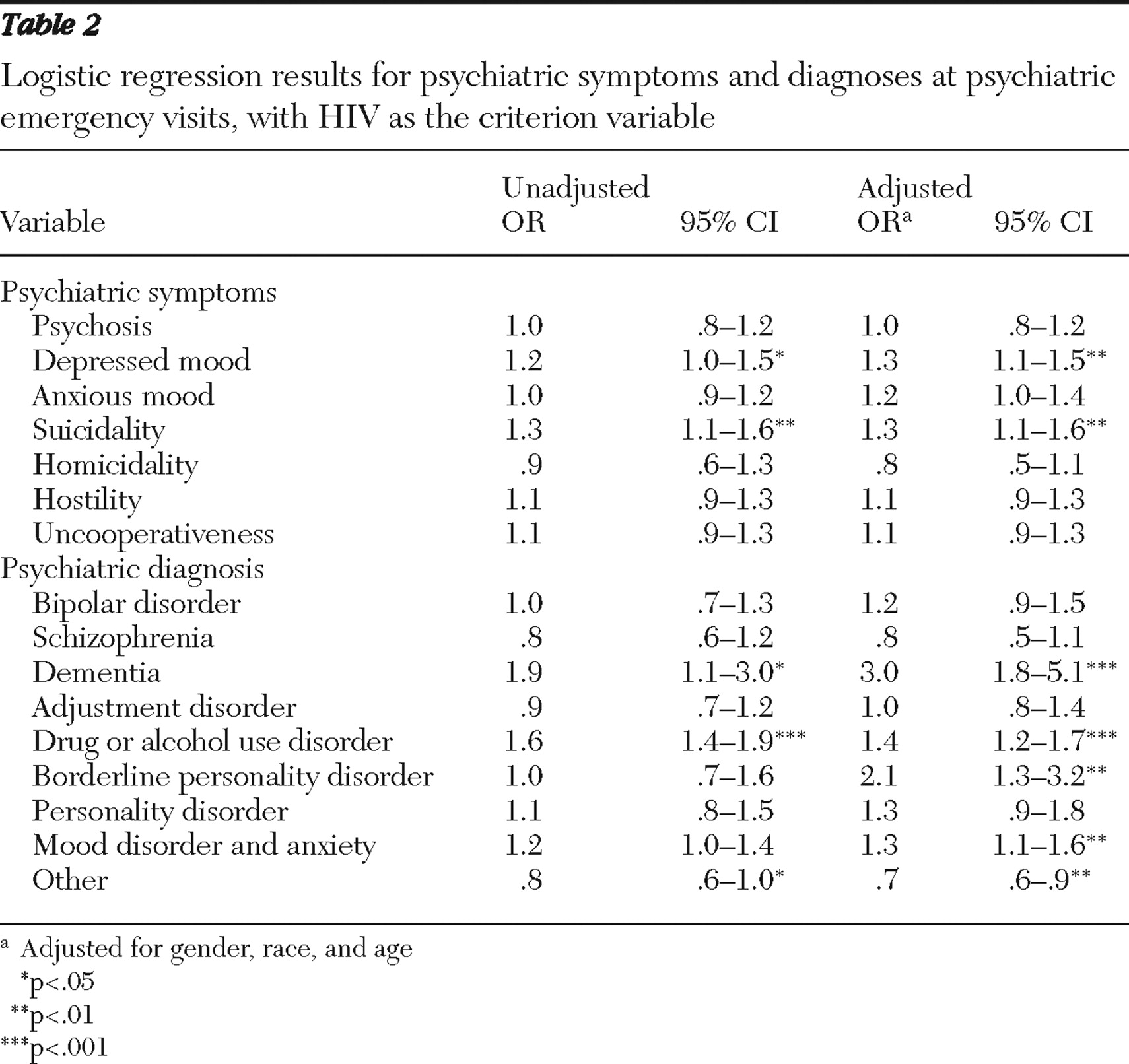

Table 2 . With the analyses controlling for gender, race, and age, we found that HIV-positive visitors were more likely to present with symptoms of suicidality (OR=1.3, CI=1.1–1.6). They were also more likely to have a diagnosis of dementia (OR=3.0, CI=1.8–5.1), borderline personality disorder (OR=2.1, CI=1.3–3.2), or substance use disorder (OR=1.4, CI=1.2–1.7).

Discussion

Although this is the first study to evaluate the prevalence of HIV infection and characteristics of HIV-positive patients treated in a psychiatric emergency department, a number of similar studies have been completed in inpatient psychiatry wards, outpatient psychiatry clinics, and emergency departments. However, over the past quarter-century, the nature of the HIV-AIDS epidemic and the characteristics of the patients infected have changed significantly, making comparisons difficult between our results and those of studies completed more than 15 years ago in inpatient psychiatry wards and emergency departments. Earlier studies determined HIV infection by blood samples in an era in which most patients were not aware of their HIV status. In contrast, this study examined the prevalence of known HIV infection among patients treated in a psychiatric emergency department, similar to recent studies in outpatient psychiatry (

3 ). Nevertheless, the HIV infection prevalence rate in psychiatric emergency departments (2.0%) is comparable with that in outpatient psychiatry (1.2% prevalence of known HIV infection) (

3 ) and more specialized emergency departments serving as trauma centers (.5%–3.5%) (

4,

5 ) but is considerably less than the prevalence in psychiatric inpatient populations (5.2%–5.5%, with prevalence determined by blood sample) (

6,

7 ) or among patients with severe mental illness who are cared for in public-sector community health centers and often admitted to inpatient facilities (2.8%–4.2%) (

8 ).

In the United States, studies of HIV-positive patients utilizing emergency department services have demonstrated that these patients are more likely than HIV-negative patients to be African American and have lower socioeconomic status, less education, inadequate insurance, and later-stage HIV infection that is consistent with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's classification of C3 AIDS (

9 ). Our study produced similar results, with overrepresentation of African-American and mixed-race (that is, race other than Caucasian, African American, Asian American, and Native American) patients and greater likelihood of homelessness. Several studies in other settings, including psychiatry wards (

10 ) and public-sect or community health centers, have found that HIV-positive patients are more likely to be homeless and to have severe mental illness (

8 ). Although existing resources are specifically allocated to house homeless HIV-positive patients, these findings indicate that greater resources are needed to house these patients. These findings are consistent with greater prevalence of HIV infection among disadvantaged populations nationally (

11 ).

HIV-positive patients treated in psychiatric emergency departments were more likely to abuse drugs or alcohol, have borderline personality disorder, and present with suicidality. In previous studies, HIV-positive patients admitted to inpatient psychiatry wards (

7,

10 ) were also more likely to possess these three clinical characteristics, and HIV-positive psychiatric outpatients and patients with severe mental illness were more likely to have a substance use disorder (

3,

8 ). Impulsivity, which is commonly associated with borderline personality disorder, and drug use are established risk factors for HIV transmission. Suicidality, one of nine borderline personality traits, could also be a direct consequence of HIV infection (depression is twice as common among HIV-positive patients) or could be associated with substance use.

HIV-positive patients presenting for treatment in the psychiatric emergency department were three times as likely as other patients to have dementia (adjusted OR of 3.0), the most statistically robust finding in our study. HIV affects subcortical brain structures, producing a cognitive impairment that is clinically subtle until later stages of dementia arise. Dementia secondary to HIV is less common than a decade ago, but moderate neurocognitive impairment is more prevalent (

12 ). Assessing subcortical cognitive impairment is difficult in the emergency department and hence, likely to be underdetected. More than 12 years ago, inpatient psychiatry wards reported dementia or "organic mental syndrome" (

7,

10 ) as common diagnoses among HIV-positive patients. For patients seeking assessment of cognitive impairment, this highlights HIV infection as a potential cause for the emergency department medical provider to consider.

The demographic characteristics of HIV-positive visitors to psychiatric emergency departments fall between those of national and Seattle populations infected with HIV. Nationally 35% of HIV-positive patients are white and 77% are male (

11 ), whereas for Seattle 70% of the HIV-positive population are white and 90% are male (

13 ). Nationally 29% of HIV-positive patients attribute injection drug use as an exposure category, compared with 15% in Seattle (

11,

13 ). HIV-positive psychiatric emergency department patients are less likely than the HIV-positive population of Seattle to be white (61%) or male (84%), which may reflect greater utilization of emergency psychiatric care among disadvantaged and substance-abusing patients.

One strength of this study is the considerable size of the patient sample, with 28,817 unique patients receiving psychiatric emergency treatment in a consecutive series of 58,301 visits to a large, urban, level 1 trauma center over the course of almost a decade. Another strength is the fact that the demographic and clinical characteristics of HIV-positive patients have not been investigated in this setting. The study was limited by the regional nature of the sample and lack of ethnicity and HIV exposure categories in the database. Informative data about disposition was unfortunately either unavailable or incomplete, so we were unable to catalogue medical admission rates, involuntary or voluntary psychiatric hospitalization, and outpatient follow-up. Challenges in independently confirming HIV status led to probable underreporting of actual rates of HIV infection, because many patients were less likely to disclose their HIV status and others were unaware of it at the time of the visit. In addition, over the course of ten years, a number of patients treated at this emergency department became infected with HIV. These issues present a challenge to the accurate calculation of HIV prevalence at the patient level.