Study design and overview

Patient and visit characteristics from a nationally representative sample of community-based family, general, and internal medicine primary care physicians' office visits were used to evaluate the relationship between depression screening and office visit duration.

Data source. Cross-sectional data from the 2005–2007 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) were used (

28 ). The NAMCS is a national survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics of patient visits to non-federally employed, office-based physicians primarily engaged in direct patient care. The survey uses a three-stage probability design of primary sampling units, physicians' practices within those units, and patient visits within physicians' practices. Each visit is weighted by sampling probability, adjustment for nonresponse, physician specialty, and geographic location to obtain nationally representative estimates. These estimates were considered reliable if they had a standard error of 30% or less and if they were achieved with a sample of no fewer than 30 patient visits (

28 ). This study was exempt from review by the University of Oklahoma Institutional Review Board because it used publicly available, deidentified data.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. The 2005–2007 NAMCS data contained 87,835 unique visits. The USPSTF depression screening guidelines target adult patients of primary care physicians. Therefore, data were limited to visits including adult patients (≥18 years) of general and family practices and internal medicine physicians indicated to be the patient's primary care physician. We excluded from analysis visits with primary-reason-for-visit codes related to injuries, adverse effects, or test results; visits coded as administrative (examinations for unemployment, licensing, Social Security disability, and so on); and visits that were uncodable (that is, there was insufficient information). Because this study focused on physician time burden, visits indicating presence of nonphysician clinicians (such as nurse practitioners or physician assistants) were excluded from the analytical sample. Visit time outliers were eliminated by restricting visit time to a range from one to 60 minutes. Because only visits with complete data were analyzed in multivariable analyses, all visits containing variables of interest coded as missing were excluded, leaving a final analytical sample of 14,736 family, general, and internal medicine primary care adult office visits in the United States between 2005 and 2007.

Study variables. The dependent measure of interest was duration of physician time spent with a patient for a particular visit. Time spent with physicians is defined in the NAMCS data documentation as the amount of time (in minutes) that a physician spent with the patient, not including time spent waiting for an appointment or with another type of practitioner (

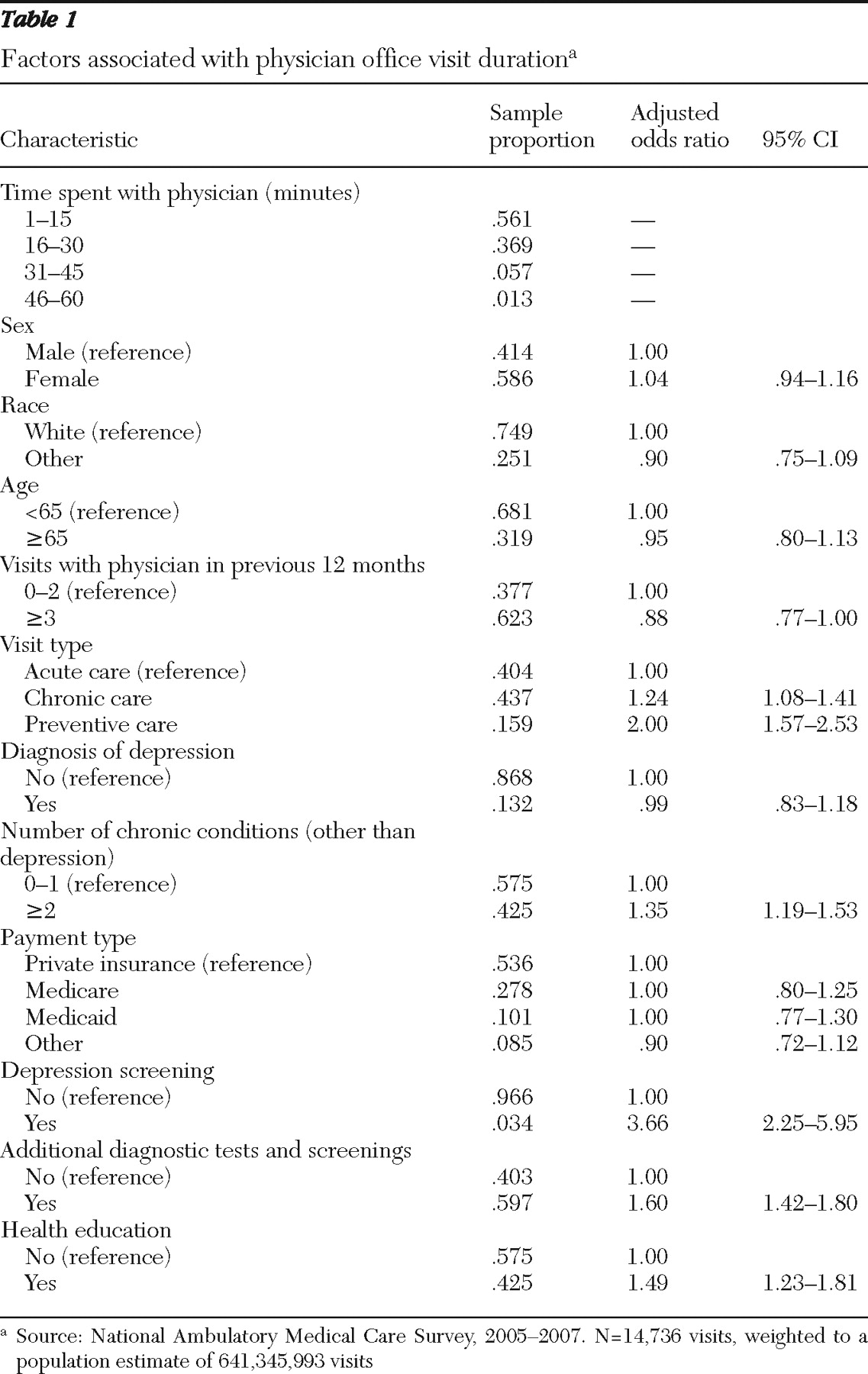

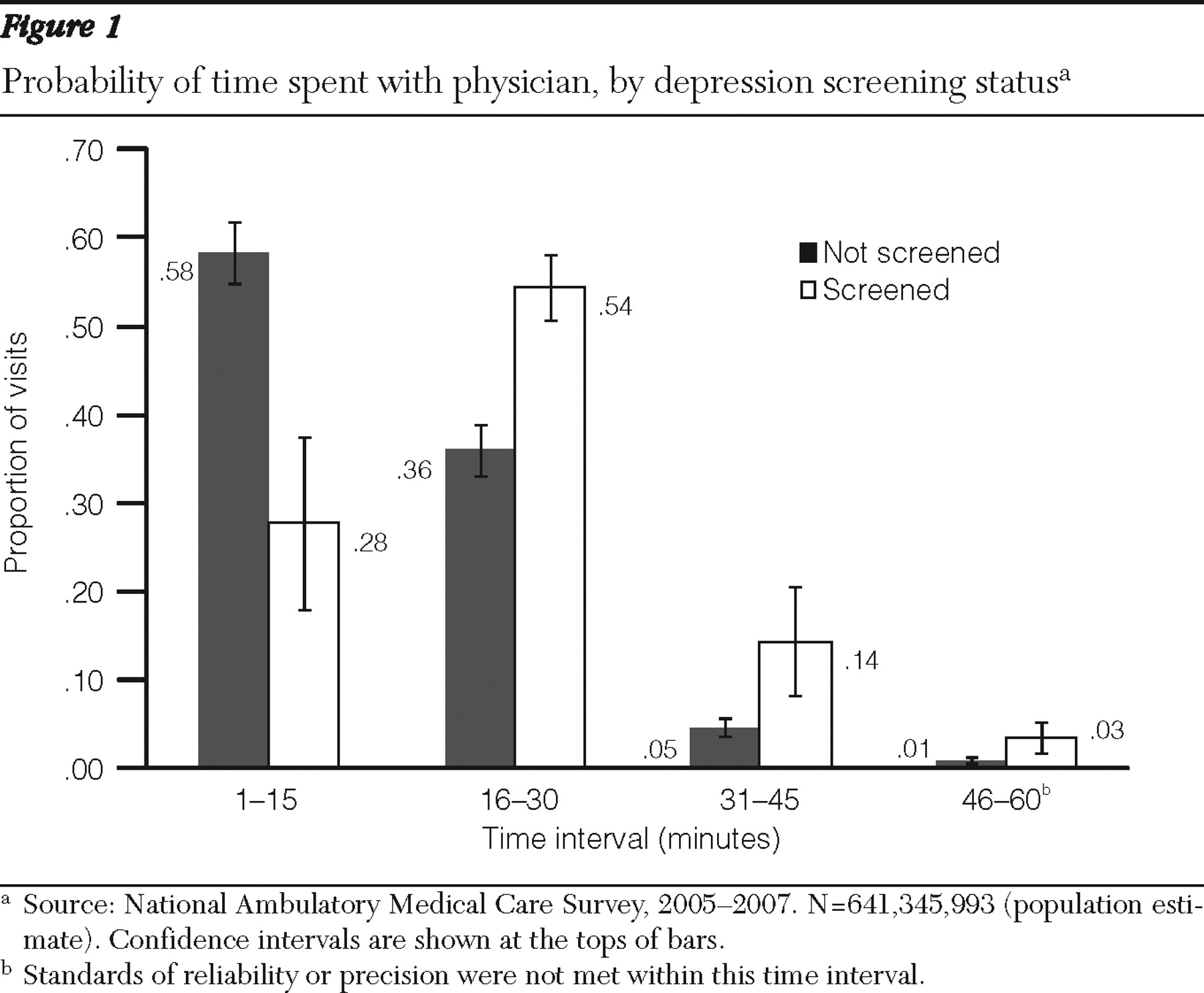

28 ). Although defined as a continuous variable, the distribution of time spent with a physician in the NAMCS data was largely recorded in increments of five minutes of visit duration (five minutes, ten minutes, 15 minutes, and so on). To preserve the nature of the data while balancing the need for adequate sample sizes to achieve reliable estimates in data analysis, we defined the duration of time spent with a physician at an office visit as an ordinal measure of four 15-minute time increments (that is, one to 15 minutes, 16–30 minutes, 31–45 minutes, and 46–60 minutes). Prior analyses that have examined physician time using NAMCS data (

26,

29 ) dichotomized the time variable at the median visit duration. However, an ordered measure provides a more precise estimate of the associations between depression screening and physician time while respecting the analytical assumption of the nonnormal distribution of the data.

Several patient characteristics were used as control variables in the multivariable analysis. Age was dichotomized as patients aged 65 or older or those younger than 65. Race-ethnicity was defined as white non-Hispanic or "other" (including black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, or people of multiple races or ethnicities). The NAMCS documents 14 common chronic conditions, regardless of the diagnosis associated with that specific visit. Given its suspected relationship with depression screening, a diagnosis of depression (yes or no) was included as a separate control variable in the analyses. Of the 13 remaining possible, chronic conditions, the sum of the total number of chronic conditions was dichotomized as patients with more than the median number of chronic conditions or those with the median number or fewer.

Several visit characteristics were also suspected to be related to visit duration. An indicator variable was created to document the number of prior visits a patient had made to the sampled physician in the previous 12 months. This variable was dichotomized as patients with up to two prior visits versus those with three or more prior visits. Primary payment type was defined as private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, or other, which included worker's compensation, self-pay, no charge, other, or unknown. The NAMCS data also document the order for or provision of numerous diagnostic or screening tests. The independent variable of primary interest in this study was order for or provision of depression screening documented in the patient medical record. Depression screening was defined separately from the other diagnostic and screening tests by a dichotomous variable (yes or no). Because the data collected in the NAMCS regarding diagnostic and screening tests are limited to the description of "order for or provision of" a given test, the meaning of the term "depression screening" as used in this study was defined as physician intent to screen the patient for depression.

All other diagnostic and screening tests were collapsed into a single dichotomous variable indicating at least one test versus no tests. Measurements of vital signs, height, and weight were not included as diagnostic tests in the analysis because they are standard practice at family, general, and internal medicine primary care visits. The order for or provision of health education at a visit was dichotomized as yes or no. A final indicator variable for visit type was used to identify an acute care, chronic care (including routine and flare-up chronic care), or preventive care visit.