Access to behavioral health care remains a major public health concern in the United States (

1,

2,

3,

4 ), most acutely affecting people who have low income or are uninsured (

5,

6,

7 ). One promising approach is to locate behavioral health specialists in primary care settings. Such arrangements can improve utilization and outcomes, especially for patients with access barriers (

8,

9,

10,

11 ). However, such integrated models have been difficult to implement, largely because of restrictions on reimbursement (

12 ). As a result, advances in provision of specialty mental health care in primary care settings have occurred largely in systems that combine insurance and care provision, such as Kaiser Permanente in California and the Veterans Health Administration (

13 ).

An interesting exception is the network of over 1,000 community health centers around the United States that provide primary care in medically underserved areas. Here, the patient population is largely a mix of Medicaid beneficiaries and uninsured individuals, but direct federal subsidies may also support integrated care. In 2008 these facilities served over 17 million people, 35% of whom were insured through Medicaid and 38% of whom were uninsured (

14 ). What role does this population of organizations play in providing integrated behavioral health care to the underserved in the United States?

A previous study found that the proportions of community health centers offering behavioral health care increased between 1998 and 2003. The numbers of behavioral health care visits and patients were also substantially higher in 2003; however, given stable numbers of behavioral health care staff per community health center, numbers of visits per patient dropped sharply (

15 ).

Like other primary care facilities, community health centers have had difficulty securing reimbursement for behavioral health care (

16 ). In 2002 the federal government sought to reduce these obstacles by directing state Medicaid agencies to pay for mental health services provided by primary care as well as specialty providers at community health centers (

17 ). At the same time, the Bush Administration began a health center initiative underwriting both new community health centers and expansion of existing facilities, resulting in an increase in overall federal funding from $1 billion in 2001 to $2 billion by 2007 (

18 ). During this period, a total of $7.2 million was awarded specifically for mental health service expansion to 50 community health centers. Thus the health center initiative may have both directly and indirectly enabled community health centers to continue their expansion of behavioral health care services, with potentially significant access implications for the underserved.

Two questions were addressed in this study: first, how do trends in community health centers' provision of behavioral health care services during the first six years of the health center initiative (2002–2007) compare with trends just prior to the initiative (1998–2001)? Second, were these trends the same for mental health services, 24-hour-type crisis services, and substance abuse treatment?

Methods

The primary data source used in this study was the Uniform Data System, a set of electronic files compiled by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) from reports submitted annually by all U.S. federally funded community health centers on administration, patient population demographic characteristics, utilization, and finances. Whenever data were available at the health center level, we used those, validating them against the totals provided by HRSA in their annual aggregate reports (

19 ). For measures not released at the community health center level, we relied exclusively on the aggregate reports (

19 ). We used calendar year 1998–2007 data to compare trends in mental health and substance abuse service provision before and during the health center initiative, which began in fiscal year 2002.

We used three indicators of whether each community health center offered specialty mental health and substance abuse treatment services on site (each a yes-no item). Specialty mental health services were defined in the Uniform Data System documentation as "mental health therapy, counseling, or other treatment provided by a mental health professional" (

20 ). Crisis mental health services were defined as mental health services offered on a 24-hour basis. Substance abuse treatment was defined as "counseling and other medical and/or psychosocial treatment services provided to individuals with substance abuse (i.e., alcohol and/or other drug) problems" (

20 ).

Two measures were used to indicate the numbers of specialty behavioral health services encounters: number of encounters each year with mental health specialists, including psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists, social workers, family therapists, and other "professional mental health workers" providing counseling or other mental health treatment and number of encounters with substance abuse specialists each year, including those with nurses, clinical psychologists, social workers, and substance abuse treatment professionals.

In its counts of patients served by mental health specialists, the Uniform Data System did not include until 2004 patients who saw psychiatrists. We therefore used counts of behavioral health patients and encounters per patient based on three types of primary diagnosis, each reported annually as a single number by each community health center on the basis of groups of billing codes: mental disorder excluding substance use disorder; alcohol use disorder; and drug use disorder. Individuals could be categorized as having different primary diagnoses at different times; thus a sum of patients across categories would overstate the total number of individuals using these centers. However, the measures indicate how many people presented at least once a year with mental, alcohol use, or other substance use disorders as their primary condition. Unlike the two previously described measures of encounters with specialty behavioral health care providers, these three measures based on patient diagnosis did not distinguish between treatment provided by specialty versus primary care providers. They also did not identify the nature of each encounter, such as counseling versus medication management. Reporting the number of patients in each of these categories was optional until 2000; we therefore used only 2000–2007 data for these measures.

For the counts of patients described above who had primary diagnoses of mental disorders or substance use disorders, we also calculated the mean number of encounters per patient each year for each diagnostic group by dividing the sum of encounters across all community health centers by the total number of patients in that group.

We used logistic regression models estimating associations between time and provision of each service within each period (1998–2001 and 2001–2007) to determine whether the odds of an individual community health center's offering each service changed significantly over that time. We used Student's t tests to compare changes over time in odds of providing each type of service before and during the health center initiative. Numbers of encounters and patients were based on aggregate national totals rather than on center-level data, and thus tests of significance were inapplicable.

Results

Service availability

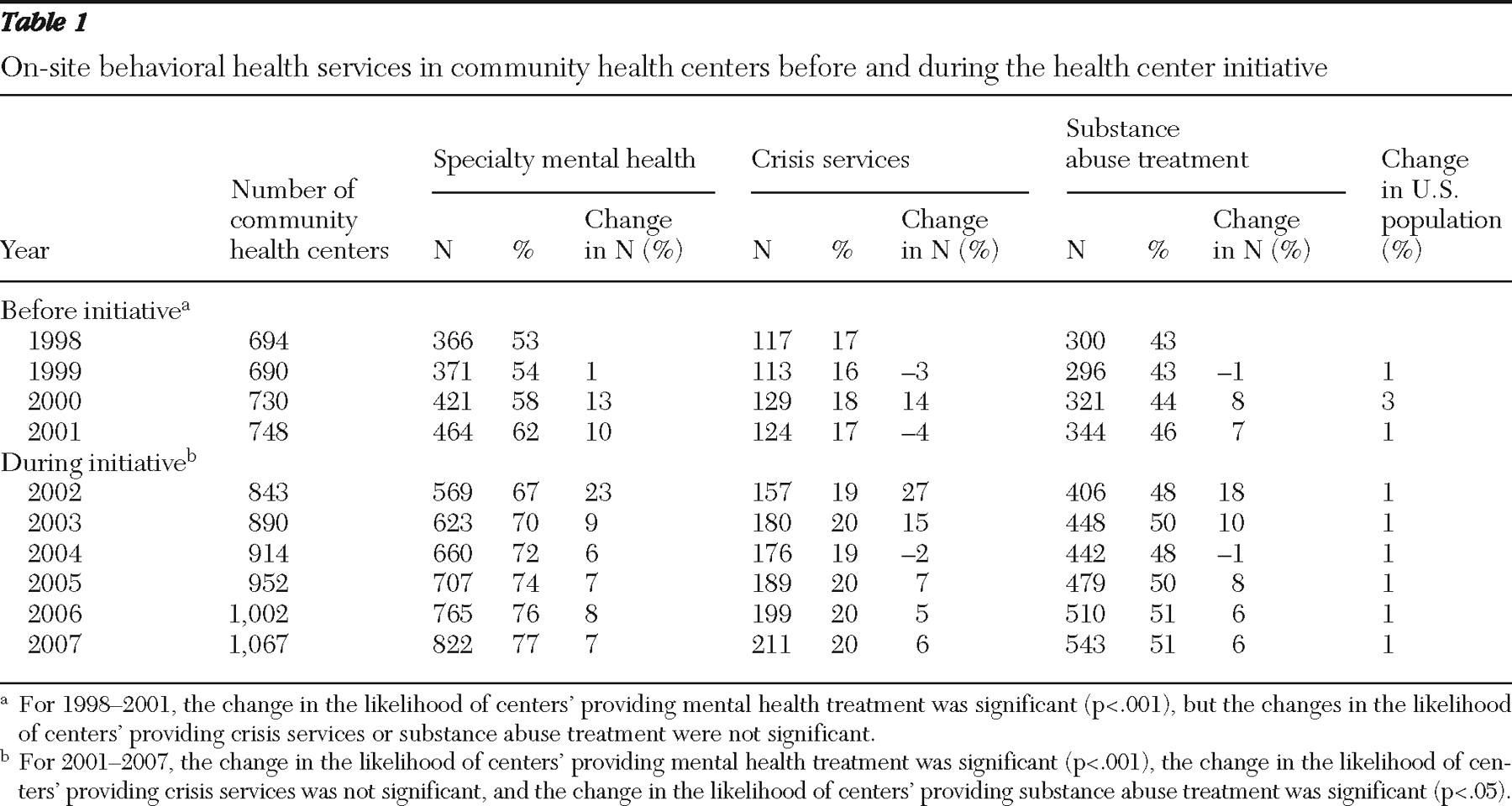

Trends in service provision are shown in

Table 1 . In 1998, 366 community health centers reported providing on-site specialty mental health services. In the three years that followed, which preceded the health center initiative, the mean annual increase in the number of community health centers reporting these services was 33, resulting in a 27% cumulative increase to 464 by 2001. Between 2001 and 2007, a mean of 60 additional community health centers each year provided these services, bringing the total to 822 (an increase of 77%). The higher annual growth during the health center initiative reflected two factors. First, the overall number of community health centers increased over twice as fast between 2001 and 2007 (from 748 to 1,067, or 7% annually) than between 1998 and 2001 (from 694 to 748, or 3% annually). Second, individual community health centers became more likely to provide these services, although not at a greater rate than before the initiative (

Table 1 ): the percentage of community health centers offering specialty mental health care on site increased from 53% in 1998 to 62% in 2001 and to 77% in 2007. The likelihood that any given community health center will offer a service is an important component of access because of the typical lack of proximate alternative sources of care.

The number of community health centers providing 24-hour crisis mental health care also increased during the health center initiative, from 124 in 2001 to 211 in 2007 (a 70% increase). However, individual community health centers did not become more likely to provide these services (

Table 1 ). As of 2007, 20% of community health centers provided crisis services.

Similarly, the number of community health centers providing substance abuse treatment increased 58%, from 344 to 543, between 2001 and 2007 (

Table 1 ). The odds that individual community health centers provided substance abuse treatment increased slightly during the initiative (OR=1.03, p<.05). This was due to a smaller confidence interval during 2001–2007 than in 1998–2001, however, rather than to a stronger trend in the latter period. The t test comparing changes in community health centers' odds of providing substance abuse treatment before and during the health center initiative was nonsignificant. In 2007, 51% of community health centers provided substance abuse treatment. Newly funded community health centers were no more likely than previously funded facilities to provide any type of behavioral health care.

Service reach

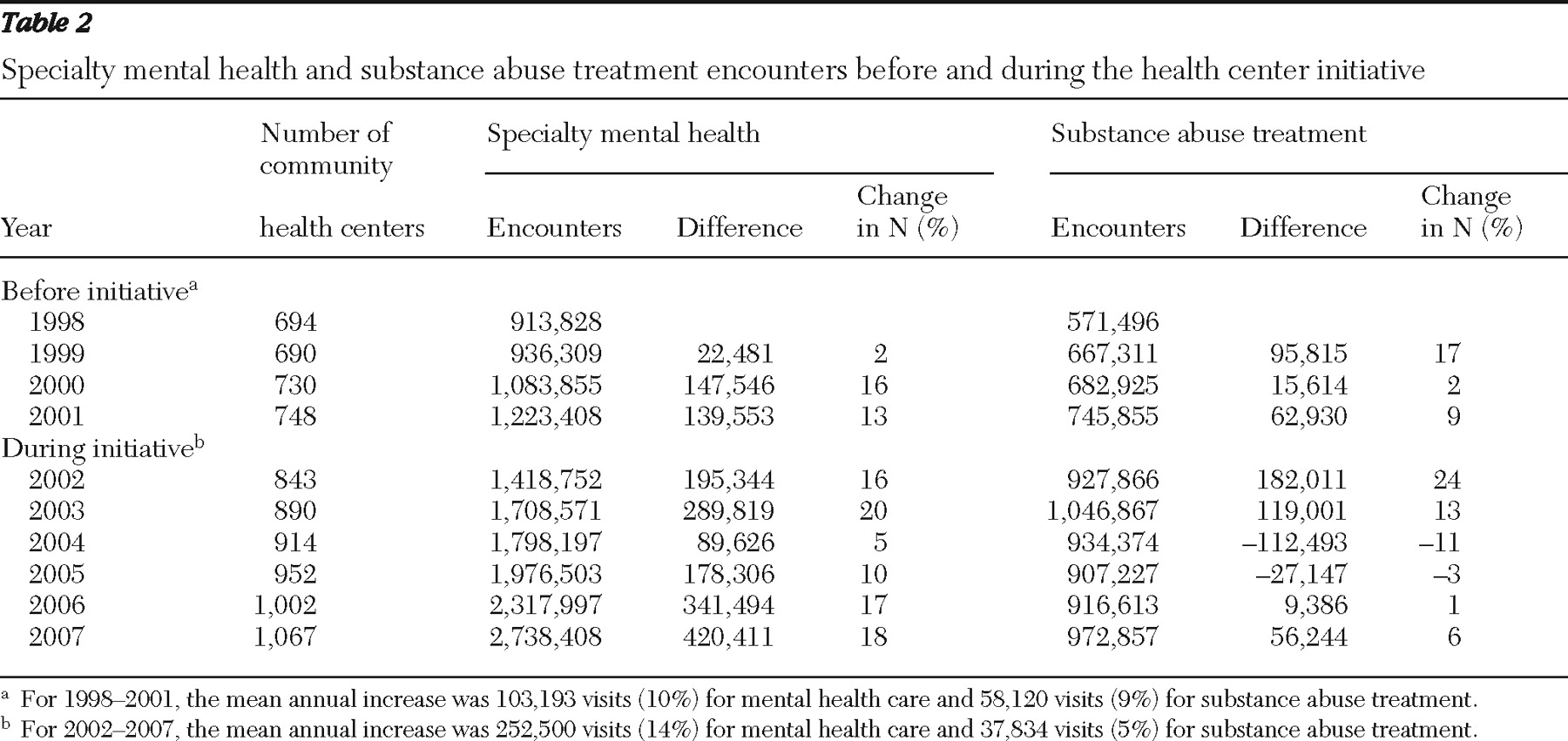

The total number of patient encounters with specialty mental health providers across all community health centers increased by 34% between 1998 and 2001, from 913,828 to 1,223,408 encounters, a mean increase of 10% per year (

Table 2 ). This trend accelerated to a mean increase of 14% per year between 2001 and 2007, when the number of encounters reached 2,738,408. In contrast, the rate of growth in number of substance abuse treatment encounters diminished during the health center initiative. The total number of substance abuse encounters rose by 31%—from 571,496 in 1998 to 745,855 in 2001—a mean increase of 9% per year. By 2007, community health centers reported 972,857 substance abuse treatment encounters, reflecting an overall growth of 30% since 2001, but an average annual increase of 5%, just over half the rate of increase before the initiative.

In contrast, the rate of growth was more uniformly positive during the health center initiative for the number of patients with primary behavioral health diagnoses receiving behavioral health care from any type of provider.

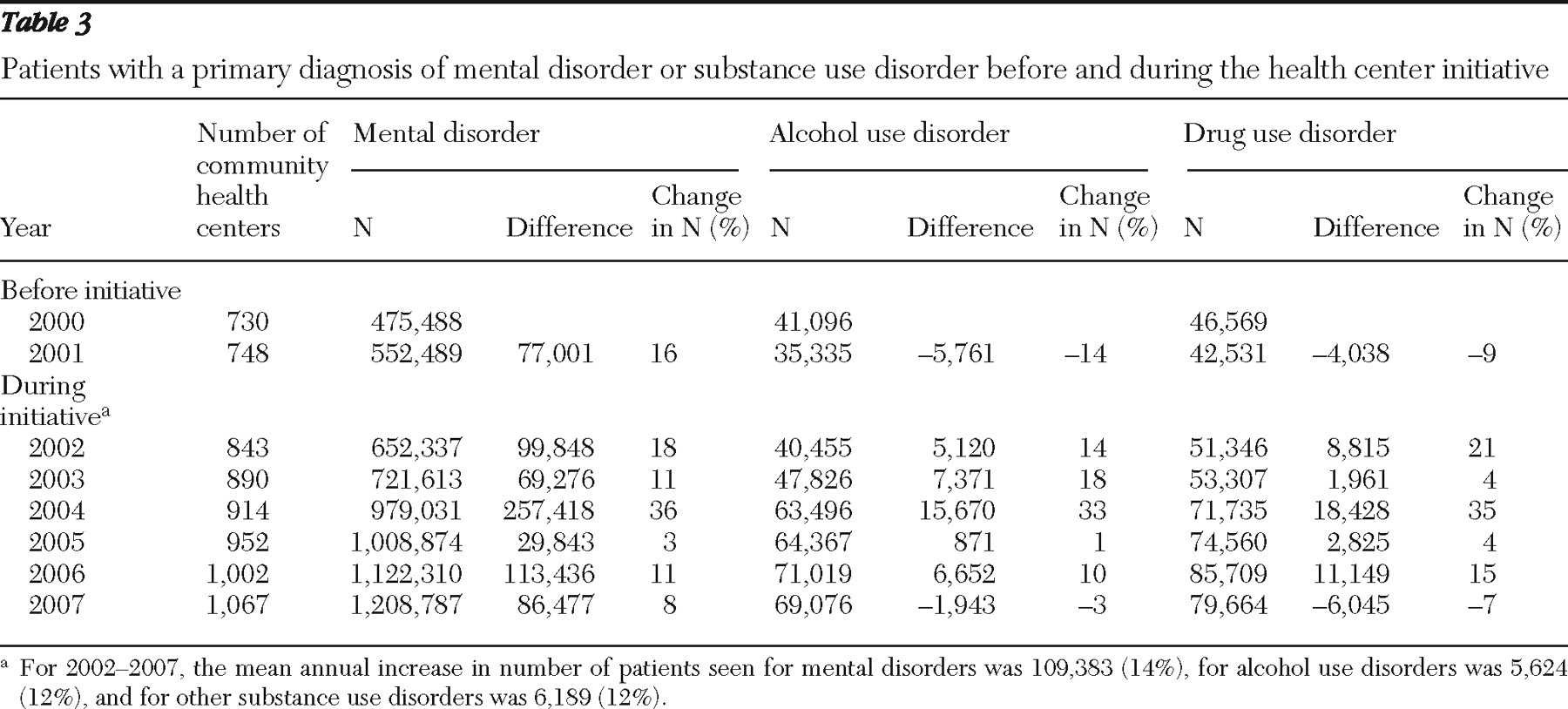

Table 3 shows trends in numbers of patients seen for behavioral health diagnoses between 2000 (the first year in which accurate numbers of patients per diagnosis type were available) and 2007. The number of patients across all community health centers treated for mental health conditions as the primary diagnosis increased 16% between 2000 and 2001. This total increased another 119% by 2007, to 1,208,787, representing a mean annual increase during the health center initiative of 14% per year. Across all community health centers, the number of patients with an alcohol-related problem as the primary diagnosis decreased 14% in the year before the health center initiative, to 35,335 in 2001. This total almost doubled by 2007, when 69,076 (a 95% increase) encounters for patients with primary diagnoses of alcohol-related conditions were reported, representing a mean annual increase of 12% between 2002 and 2007. The number of patients with a drug problem as the primary diagnosis decreased 9% between 2000 and 2001, to 42,531. That total then increased by 87%, or a mean of 12% per year, from 2002 through 2007, to 79,664 patients.

Level of service utilization

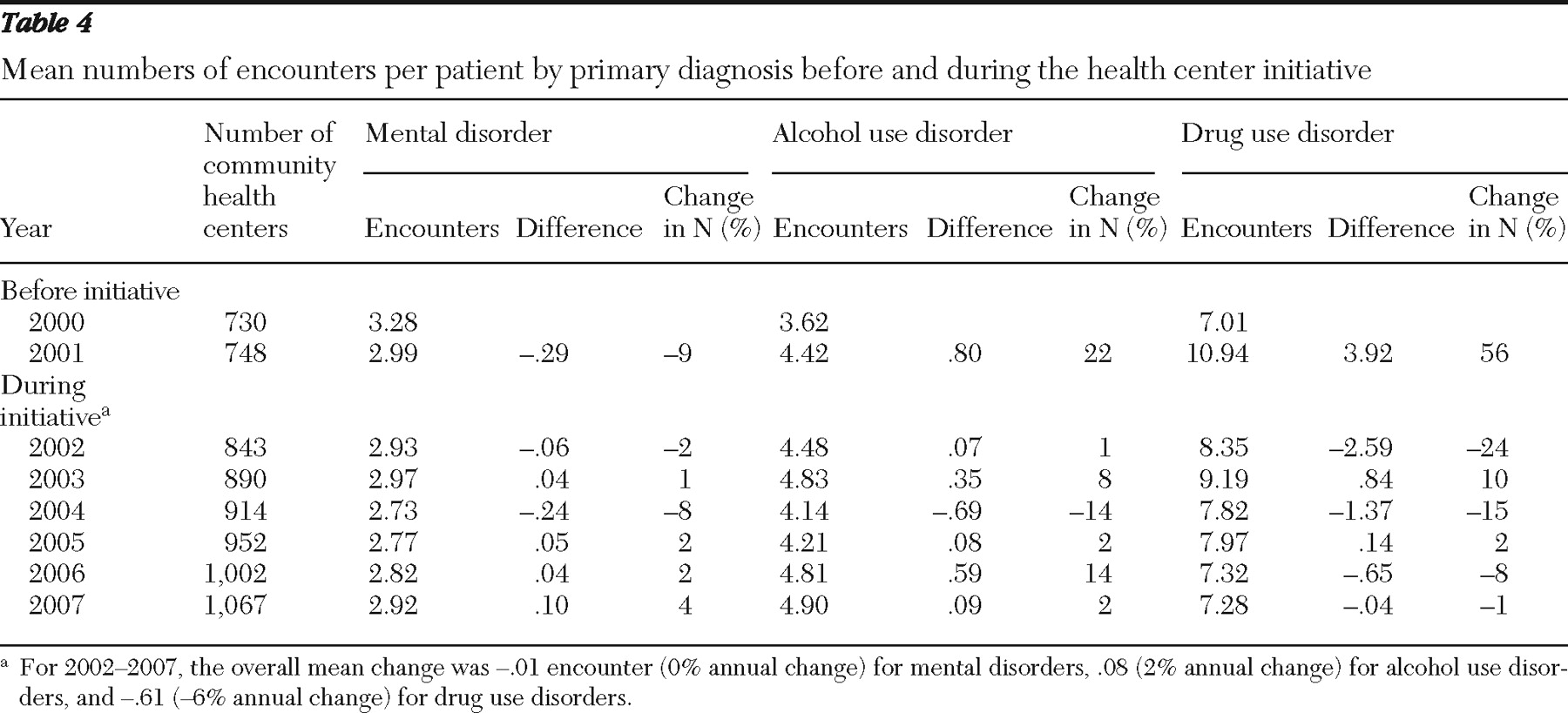

Table 4 shows 2000–2007 trends in numbers of encounters per patient with a primary diagnosis of a mental or substance use disorder. As in

Table 3, these included encounters with nonspecialists. The mean number of encounters per patient with a primary diagnosis of a mental disorder decreased from 3.28 to 2.99 between 2000 and 2001 and decreased slightly again over the next six years, to 2.92 in 2007. The mean number of encounters per patient with alcohol-related diagnoses increased from 3.62 in 2000 to 4.42 in 2001 and further increased to 4.90 in 2007. The number of encounters per patient with non-alcohol-related drug problems jumped 56% between 2000 and 2001, from 7.01 to 10.94, and then by 2007 returned to a level slightly higher than the year 2000 mean (7.28 encounters in 2007).

Discussion

Main findings

The numbers of people receiving mental health and substance abuse treatment at community health centers increased dramatically between 2001 and 2007. Some preexisting trends toward increased behavioral service provision at community health centers continued during the health center initiative, which began in 2002, and others accelerated. This growth occurred largely through an increase in the overall number of community health centers but also through continued increases in the proportions providing behavioral health care on site, especially specialty mental health services. The fact that over three-quarters of all community health centers now have mental health specialists on site marks a major advance in integration of mental health and primary health care within the U.S. safety net.

Crisis service provision at community health centers is also important for several reasons. First is the very high need, as indicated by the number of calls to U.S. crisis units, estimated in the millions annually (

21 ). Second, because of the potential to prevent suicide or harm to others, there is a narrow window of opportunity to intervene and often inadequate alternative sources of crisis care within the community (

22 ). Third, community health centers serve the people with the fewest such alternatives. The steady odds of community health center 24-hour crisis service provision found here were mirrored by consistent proportions from 1990 to 2004 of 24-hour mental health admissions to civilian hospitals and residential treatment facilities versus those to all other nonfederal organizations, including freestanding outpatient clinics, partial care organizations, and multiservice mental health organizations (

23 ). Although admissions reflect only part of crisis care, together these patterns suggest that 24-hour mental health services have not generally been shifting to ambulatory care settings. Mental health professional shortages in many areas (

24 ) as well as difficulties that freestanding outpatient facilities have had in expanding to 24-hour operations likely limit crisis service expansion options for community health centers as well as other outpatient facilities.

The good news about substance abuse treatment includes the fact that individual community health centers have become slightly more likely to provide these services, although the shift toward providing them has been much smaller than that for specialty mental health services. The recent increase in the number of patients with substance use disorders may reflect the trend toward treatment in outpatient settings and increasing public spending on substance abuse treatment, as well as diminishing private insurance coverage for these services (

25 ). These trends may lead some people who have insurance to seek treatment at community health centers. In addition, the number of encounters related to alcohol problems per patient has been trending upward over the past several years, although the number of encounters per patient for non-alcohol-related problems has decreased over that same period.

The median number of mental health encounters per patient across all community health centers was comparable to the median number of 1.7 visits in the general medical sector found in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. However, it was below the median of 7.4 visits found in the same survey for specialty mental health care settings (

26 ).

Limitations

HRSA's Uniform Data System is valuable because it provides longitudinal information about the complete census of federally funded community health centers in the United States, which are one of the largest sources of primary care for the poor and underserved in this country. However, these data do not reveal patient-level patterns of care and thus cannot speak to vital issues such as appropriateness, intensity, or duration of care. Although the Bureau of Primary Health Care provides operational definitions of all required data elements, reports from community health centers are unaudited, and the centers' information systems vary in data quality. Not all newly funded community health centers are new facilities, and thus not all newly counted services are necessarily truly new.

Because of cost-based billing requirements, a patient could have a general medical encounter and a mental health encounter on the same day but be counted as having only the general medical encounter; to that extent, the numbers in

Tables 2 –

4 understate the amount of care provided. Conversely, someone could be identified as having different behavioral health diagnoses in separate encounters within a year and thus be counted as more than one patient (

Table 3 ). The numbers of encounters reported by community health centers used in

Tables 3 and

4 also did not distinguish between those provided by specialists versus other providers. The data suggest that both specialists and nonspecialists frequently provided mental health care: 98% of the community health centers that did not provide specialty mental health services in 2007 reported treating patients for mental health problems.

Finally, we divided the total numbers of encounters for all patients nationally by the total numbers of patients in each diagnostic category to estimate encounters per patient (

Table 4 ) because medians would have to be calculated at the health center level and thus would have disproportionately weighted patients from smaller facilities. However, means do not reflect central tendencies in utilization as well as medians because some patients consume disproportionate amounts of care. We cite the 2007 national median across all community health centers above to facilitate comparison with previously reported treatment utilization rates in other settings.

Conclusions

In 2007 almost 5% of all adults in the United States reported an unmet need for mental health care (

3 ). As community health centers have increased in number and likelihood of providing specialty mental health care, these primary health care clinics have contributed to closing that gap. The trend toward provision of behavioral health services at community health centers also bodes well for faster diagnosis and better ongoing care coordination for the underserved. Both the 2009 federal stimulus package and health reform have substantially increased funding for community health centers (

27,

28 ). Although not focused on behavioral health care, these grants may indirectly enhance both mental health and substance abuse treatment through new and expanded facilities and staffing. The Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 requiring comparability between behavioral and physical health insurance may also improve private insurance payments and thus help underwrite service provision. Collectively, these factors hold promise of edging closer to the long-held but elusive vision of community-based behavioral health care for all those in need.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was funded through grant 5K01MH076175 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the journal's reviewers as well as individuals at HRSA and the National Association of Community Health Centers who answered our questions.

The authors report no competing interests.