The state department of mental health is usually the single largest provider of mental health services for children in any state. Services are provided through direct patient care, through the management of clinical services provided by private administrative agents, or by county mental health authorities and other local government entities.

State departments of mental health usually have close working relationships with key members of the state legislative and executive branches. As a result, the department plays a strong role in shaping policy initiatives that will affect mental health services for children in both the private and the public sector. If child and adolescent psychiatry as a discipline hopes to have a leadership role in shaping mental health policy for children, child psychiatrists need to have a role in the leadership of state departments of mental health.

This paper presents the results of two surveys that examined the roles child psychiatrists currently play in formulating public mental health policy, describes barriers to their involvement in this area, and makes recommendations for improving the leadership role of child psychiatrists.

Methods

A preliminary point-in-time survey was developed to obtain information on the role child psychiatrists play in the central administration of departments of mental health. The survey used closed- and open-ended questions to ascertain what administrative roles child and adolescent psychiatrists play in central management of departments of mental health and what barriers might exist to their taking on administrative roles. With the assistance of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, the survey was sent in August 1997 to the director of the department of mental health in each of the 50 U.S. states and five territories.

Based on responses to the preliminary survey about skills or knowledge that child psychiatrists lacked, making them less suited for leadership positions than members of other disciplines, we developed a second survey focused more narrowly on children's services. The second survey was distributed in February 1998 to directors of children's services in state departments of mental health through the children's services division of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors.

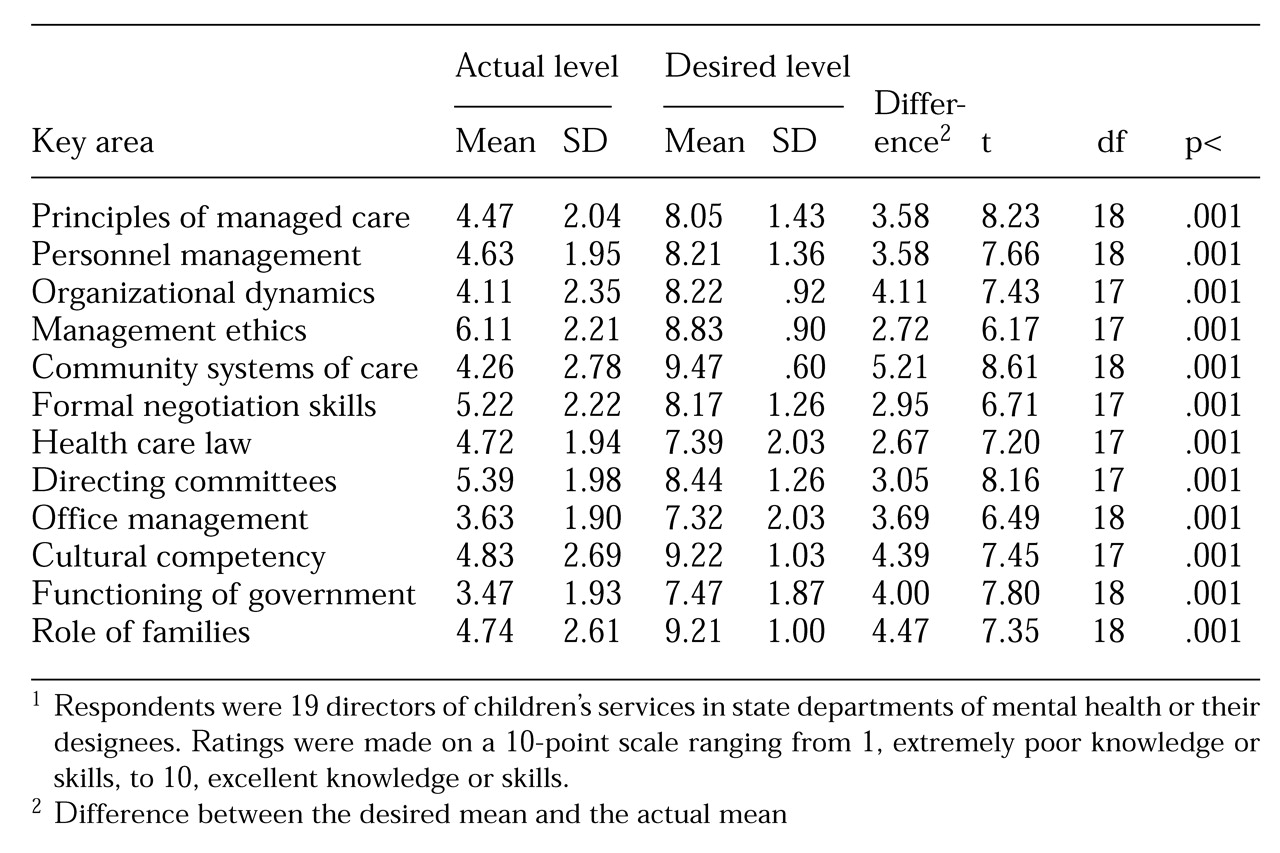

The second survey asked respondents to assess the knowledge level of most child psychiatrists in 12 key areas on a scale of 1 to 10, on which 1 indicated extremely poor knowledge and 10 indicated excellent knowledge of the topic. Brief descriptions of the 12 key areas were provided (see accompanying box). On a second 10-point scale, respondents were asked to indicate the level of knowledge child psychiatrists would need to assist effectively in developing policy and addressing administrative issues in state departments of mental health. Differences between the ratings on the actual knowledge scale and the desired knowledge scale were tested for statistical significance using t tests (two tailed) for correlated samples.

Participants in both surveys were assured that their individual responses would be kept confidential and would be reported only in aggregate.

Results

The first survey

Respondents from 31 of the 55 states and territories returned surveys. Eleven respondents were located in the Midwest, nine in the East, six in the West, and five in the South. Respondents were directors of state departments of mental health or their designees. Fourteen respondents were psychiatrists, and seven were child psychiatrists. Six respondents were master's-level social workers or family services specialists, five were psychologists, and four had management or administrative backgrounds. The disciplinary background of two respondents was unknown.

Seven surveys were completed by the director of the state department of mental health. The others were delegated for completion by the state medical director (11 surveys), by children's services administrative staff (11 surveys), and by administrators in other roles (two surveys). We found no significant differences between the responses based on professional background or administrative role.

Nine respondents reported that the state had formally created a position for a child psychiatrist who served as an administrative consultant for children's programs. One respondent reported that the state was developing such a position, and two reported that the state was using child psychiatrists in an administrative capacity on a trial basis to determine if establishing such a position would be beneficial.

Of the formally established positions, six had been created in the last six years. The only full-time-equivalent (FTE) position was being converted to a part-time position. The others were .6 FTE or less. The duties of these consultants were quite varied. All performed clinical-administrative consultation to help develop new programs and improve existing ones or improve services to difficult clinical populations. Five helped guide policy recommendations and develop budgets. Other roles included coordinating training efforts, conducting utilization reviews, serving as a liaison to other agencies that serve children, and guiding special projects or task forces. Respondents were asked if the state would keep the position in the face of a 10 percent administrative budget cut. They indicated that five states would keep the position, one would not, and three were undecided.

Twenty-two states had no formalized administrative role for child psychiatrists. Only seven of these states consistently obtained input from clinicians in the field on administrative issues. Many respondents cited barriers that prevent child psychiatrists from having roles in central administration. Nine held that child psychiatrists were hard to recruit to meet clinical needs, much less to act as administrators. Eight indicated that budgetary issues and the expense of child psychiatrists were significant barriers to using them in central administrative capacities. Six thought that child psychiatrists do not understand how government systems work, lack basic administrative skills such as personnel management and financial management, or are unfamiliar with the array of nontraditional services being developed in state systems to provide for a full continuum of care. Only one of these six respondents indicated that the state had a child psychiatrist functioning in an administrative role.

Three respondents indicated that because most of the state's services were provided to adults, children's psychiatric services did not need an administrative child psychiatrist. Other individual responses suggested that a general psychiatrist serving as overall state medical director would have enough knowledge of child psychiatry to provide input when needed, that child psychiatrists wanted to dictate courses of action rather than negotiate, and that psychiatrists were not generally used in central administration. Two respondents indicated that their states had just never thought of having a child psychiatrist on the central staff.

Child psychiatrists did function in roles not specifically designed for the subspeciality. Five child psychiatrists served as medical director or assistant medical director for all psychiatric services, one served as state director of mental health, and one served as director of children's services. Only six respondents reported that a child psychiatrist had ever been the director of children's psychiatric services for their state's department of mental health. In three of these cases, no child psychiatrist had held the position of children's services director in more than a decade.

The second survey

Twenty-one responses were obtained from the 55 surveys that were distributed. Two surveys were dropped from the analysis because they were completed improperly. Of the 19 respondents whose surveys were used in the analysis, six had a background in psychology, five in health care administration, and four in psychiatry. Three were master's-level social workers. The disciplinary background of one respondent was unknown.

Eleven respondents were state children's services directors, five were other staff in the children's services division, and three were child psychiatrists providing services to the administration of the department of mental health. Survey responses from seven states and territories in the East, five in the West, four in the South, and three in the Midwest were used in the analysis. We found no significant differences in the responses based on the respondents' professional field or current administrative role.

As

Table 1 shows, policy makers rated the actual knowledge of child psychiatrists in all 12 areas included in the survey as significantly below the desired level of knowledge expected of persons involved in policy development. A post-hoc analysis, with Bonferroni correction, revealed no significant differences in ratings based on respondents' occupation or geographic location. Child psychiatrists were rated lowest in their understanding of systems of care beyond inpatient and outpatient interventions such as medication and psychotherapy. They were considered deficient in their knowledge of principles of case management, in their skill in designing programming for a full continuum of care, and their likelihood of using nontraditional wrap-around services.

Policy makers also rated child psychiatrists as having a poor understanding of the role of families in public mental health. Respondents indicated that public systems prefer to view families as powerful resources whose strengths should be enhanced, while child psychiatrists tend to view families as sources of pathology. Other major deficiencies were perceived in knowledge of cultural competency, organizational dynamics, and the functioning of government.

Respondents rated child psychiatrists as relatively knowledgeable in management ethics, health care law, and formal negotiation skills. Fourteen respondents indicated they would make greater use of child psychiatrists in policy development, at least as part-time consultants, if they found child psychiatrists who were better trained in the areas covered in the survey.

Discussion and conclusions

Before discussing the results, potential weaknesses of the study must be noted. First, although survey responses were received from states that were geographically representative of major regions of the U.S., the moderate response rate may reflect a selection bias that limits the generalizability of the findings. Respondents with strong feelings on the subject may have been more likely to reply, which may have skewed the results. In addition, many surveys were completed by staff other than the department or service directors to whom the survey had been sent. Thus the survey responses should be interpreted as the opinions of the population who actually completed the survey.

Second, one must be cautious about making recommendations based on policy makers' perceptions of child psychiatrists. Perceptions may not reflect reality. However, these perceptions belong to key policy makers who control whether child psychiatrists have a "place at the table." If these perceptions are wrong, then child psychiatrists still must demonstrate that fact to the policy makers. A follow-up study that would examine respondents' experiences with child psychiatrists, including how long and how closely the respondents have worked with child psychiatrists and in what settings, could help clarify whether these perceptions are wrong.

Third, the results reflect a point-in-time snapshot of policy makers' opinions. Longitudinal surveys would be needed to determine if these perceptions of child psychiatrists are persistent in public mental health or are merely a transient finding reflecting the opinions of people in authority at this time. Finally, the survey instruments have not been standardized or otherwise tested. For the second survey, no comparative data showing how other disciplines would have fared in terms of actual or ideal levels of knowledge are available.

With these limitations in mind, the survey results can be used to paint a picture of the ideal child psychiatrist likely to be recruited to assist in public-sector policy development. This psychiatrist is a skilled clinician who is familiar with the strengths and weaknesses of common public-sector treatment options, such as family preservation programs, therapeutic foster homes, or wrap-around services. The psychiatrist is comfortable with using these services, rather than inpatient or long-term residential services, when a child's condition is deteriorating.

Although the ideal child psychiatrist understands how family dynamics may contribute to a child's psychopathology and may recognize the need for family members to change, he or she is willing to build on the family members' strengths in a culturally sensitive way and to redirect staff who focus on their weaknesses. The psychiatrist truly believes that usually, with the proper supports, the child will be better off with parents who have some flaws than in a residential institution.

Being sensitive to the professional dynamics of the organization, the ideal child psychiatrist can effectively negotiate with other professionals when there are differences of opinion and is a skilled, considerate manager of personnel. The psychiatrist stays informed about current general trends in health care administration, the law, and public health policy and looks for ways to apply them to public-sector concerns. The psychiatrist does not try to dodge administrative assignments, but accepts them willingly and works diligently on them with a view that such tasks are the price one pays to have a place at the policy table.

We have three recommendations to encourage the development of child psychiatrists who are more likely to be recruited for policy development work in the public sector. First, public child mental health services are increasingly being provided in mobile family preservation programs, family treatment homes, and other settings outside traditional clinics. Children in crisis are managed by mobilizing a flexible array of wrap-around services rather than by admitting them to a hospital. Child psychiatry residency programs need to ensure that trainees have a rotation in a public child psychiatry program, either as required curriculum or as an elective. Current accreditation standards for child psychiatry residencies do not include training in public-sector programs as a requirement (

11). Practicing psychiatrists need to expand their familiarity with these new services and training strategies. Recent contributions in the literature reflect this trend (

12,

13).

Second, the administrative content of child psychiatric training programs must be broadened beyond discussions of managed care. This training should include a didactic series, provided throughout training, on personnel management, work motivation theory, quality improvement and outcomes measurement, financial management and budgeting, negotiation skills, public mental health systems, and organizational dynamics. Lectures should be supplemented by supervised administrative experiences, such as serving on a quality improvement committee, throughout training.

This preparation will produce child psychiatrists who are better equipped to assume both clinical and administrative leadership roles in settings that range from private practice to large public mental health systems. Current accreditation standards do not require any didactic content in administrative topics. Although accreditation standards for child psychiatry residencies require administrative experiences in which the residents function in positions of leadership, the standards are vague about what constitutes an adequate experience (

11).

Some may argue a two-year training program is barely long enough to include the required clinical curriculum, without adding an expanded curriculum in administrative skills. It could also be argued that expanded administrative training should be provided in an administrative fellowship for those interested in management. However, in today's health care environment the administrative and business aspects of medicine permeate every part of mental health. Clinical psychiatrists without administrative skills run the risk of becoming little more than skilled workers who find that steadily greater degrees of their autonomy are taken from them by managers from other fields with such skills (

14,

15,

16). Mental health care is not just a clinical profession any more. As distasteful as the idea may be, it is also a business. To ensure good patient care, psychiatrists must be fluent in the language of management.

Third and finally, child psychiatrists should consider it a privilege to be involved in the central planning of a public statewide system of care. Such work offers the chance to influence the mental health care of thousands of children. Child psychiatrists should not squander this opportunity, even if the financial compensation for this work is less than that for the same amount of time in other endeavors. As an alternative to employment of individual child psychiatrists in the central administration of public-sector systems, state delegations of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry could establish formal liaisons with their state department of mental health with the aim of providing ongoing input on children's mental health policy issues.

As public systems of care evolve, child psychiatry's influence on the direction they will take can be increased if child psychiatrists are better prepared to take on leadership roles in these systems. Child psychiatry residency programs can help improve child psychiatrists' potential for leadership by providing training about the wide range of treatment interventions and support services used in public-sector systems and by incorporating administrative topics and experiences into the curriculum throughout the residency. Child psychiatrists should be encouraged to consider it a privilege to be involved in planning a statewide system of care.