We know little about the use of substance abuse and mental health services by rural drug users. Research has suggested significant variation in utilization of substance abuse treatment among rural substance abusers (

1), but few differences have been reported in alcohol treatment attendance at rural and urban settings (

2).

Overall, relatively few individuals with substance use disorders seek formal treatment (

3,

4). Substance abuse treatment is generally less available to rural residents (

1,

5), partly because some rural areas do not have local programs. Persons with substance use problems use mental health treatment more than substance abuse treatment. For example, in the 2002 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 9.7% of adults with substance use disorders used specialty treatment during the past year, compared with 22.4% who utilized mental health services (

6).

One study of individuals with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders, most of whom lived in urban areas, found greater subsequent use of mental health service use than substance use services (

7). We have little knowledge about the services use trajectories of rural populations with substance use disorders, including whether such individuals move between substance abuse and mental health service sectors or how utilization may vary over time.

This report examined the rates of substance abuse and mental health service utilization over time among a longitudinal sample of rural users of the stimulants cocaine and methamphetamine.

Methods

Data came from a natural history study of 710 stimulant users residing in rural counties of Arkansas, Kentucky, and Ohio. The sample is described in detail elsewhere (

8,

9). Counties were classified as rural according to the federal Office of Management and Budget definition of a nonmetropolitan county, or a county with a population of 50,000 or fewer persons. Participant eligibility criteria included not being enrolled in formal treatment for a substance use disorder within the past 30 days, being aged 18 years or older, having used cocaine or methamphetamine in the past 30 days, and having a verifiable address in one of the study counties.

Participants were recruited using respondent-driven sampling, a variant of snowball sampling (

10) described in earlier publications (

8). Study staff members recruited individuals through a variety of community activities who could serve as “seeds” by spreading word of the study. Those who completed the baseline interview were asked to give referral coupons to people they knew who used drugs. Seeds received $10 per contact for up to three contacts, but up to six referrals per individual were allowed.

The study was approved by the pertinent institutional review boards, and the researchers received a certificate of confidentiality. Trained research assistants conducted the written informed-consent process and face-to-face baseline and follow-up interviews. Follow-up interviews were conducted at six-month intervals for the next 36 months, culminating in a follow-up participation rate of 73%.

At each interview, participants were asked about their recent utilization of substance abuse treatment and mental health services. At baseline they were asked about their use of services in the past three years, and subsequent follow-up interviews asked about use in the previous six months.

We constructed a matrix of all data collected about use of services by individuals at baseline and at each follow-up period. We constructed one-step transition probabilities between the two types of service use for each consecutive pair of interviews using all possible respondents per pair. Our goal was to explore the long-run behavior across each one-step transition probability matrix. In other words, we wished to examine the resulting steady-state probabilities among our multiple one-step transition matrices. There was no assumption of time homogeneity.

Results

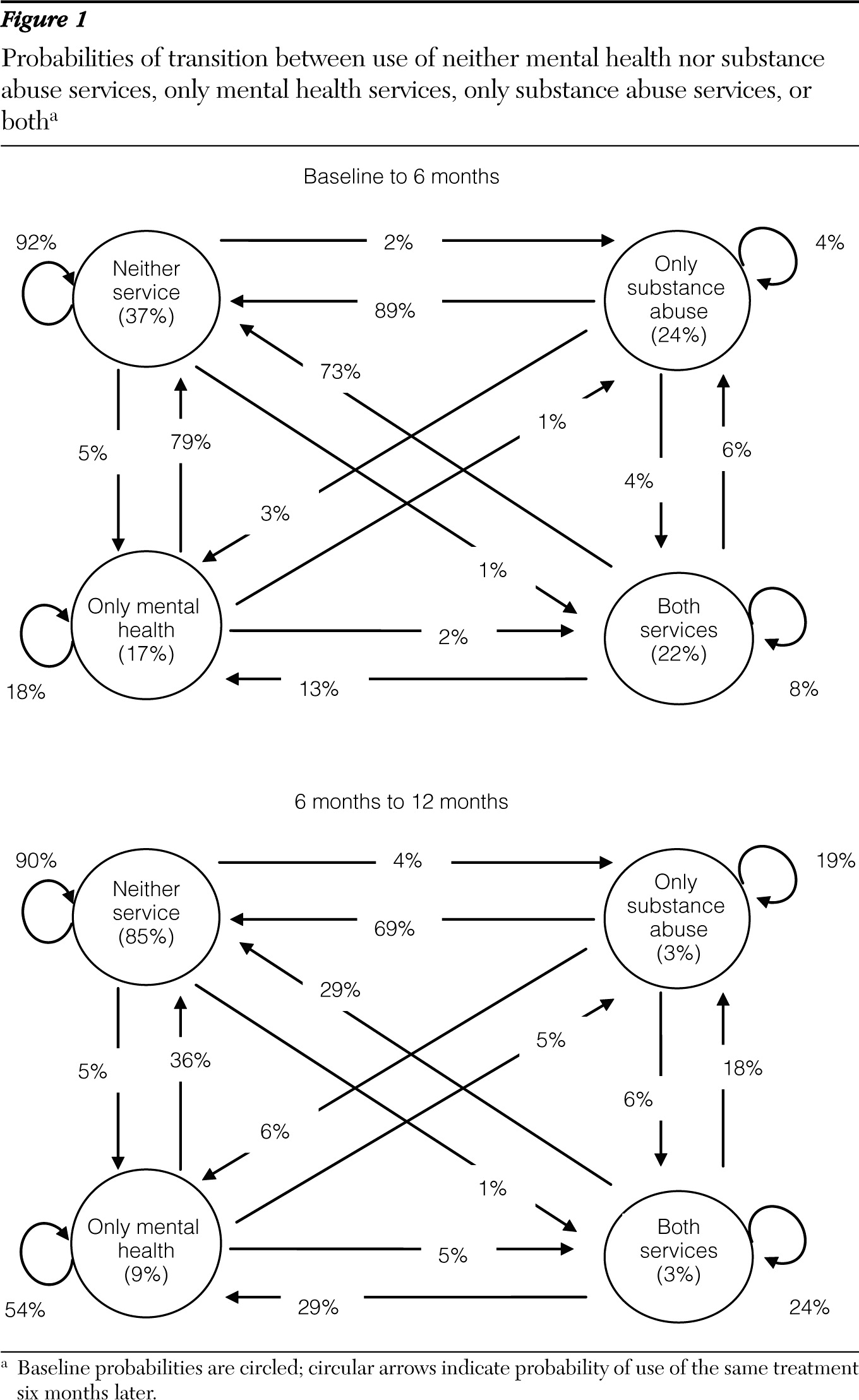

A total of 710 participants were interviewed (N=603 at six months, N=581 at 12 months, N=574 at 18 months, N=560 at 24 months, N=561 at 30 months, and N=519 at 36 months). At baseline, 37% of the total sample reported receiving neither substance abuse nor mental health treatment in the previous three years; 22% had received both; 24% had received substance abuse treatment but not mental health treatment; and 17% had received only mental health treatment (

Figure 1).

Ninety-two percent of participants who reported receiving no treatment at baseline continued to report not receiving services at the six-month interview (

Figure 1). Overall, transitions between treatment groups during the first six months of follow-up were mostly explained by participants who reported receiving services at baseline but not in the intervening six months. For example, a majority (73%) of participants who reported having received both mental health and substance abuse treatment at baseline had not received either service during the six-month follow-up; 13% had received mental health services, and 6% had received substance abuse services.

Repeated use of the same services occurred most often among participants who reported receiving mental health services but not substance abuse services. On average, the probabilities of receiving the same types of treatment regardless of initial probabilities were 82% for having received neither substance abuse nor mental health treatment, 10% for having received mental health but not substance abuse treatment, 6% for having received substance use but not mental health treatment, and 2% for having received both services.

Between six and 12 months, the majority of transitions were from having received services in the earlier interview to receiving no services at the next interview. If continuing services were obtained, they were more likely to be for mental health than for substance abuse treatment. This pattern remained essentially the same throughout the 36 months of follow-up. Steady-state probabilities comparing results from one interview to the next were consistent with the final set of probabilities at the 36-month follow-up. Final probabilities were 82% for having received neither substance abuse nor mental health treatment, 9% for having received mental health but not substance abuse treatment, 7% for having received substance abuse but not mental health treatment, and 2% for having received both services.

Discussion

A majority of participants who completed all seven interviews were most likely to receive no substance abuse or mental health services while they participated in the study. More received mental health services than substance abuse services, and only a few who received mental health services later transitioned into substance abuse services. The large decline in service use from baseline to six month follow-up is due at least in part to the length of the period (three years) measured at baseline.

Participants in this study reported a range of severity of mental and substance use disorders (

8,

9), and many would not have been appropriate recipients of either of these services. Although 83% met

DSM-IV criteria for a drug use disorder and 57% met criteria for an alcohol use disorder at baseline, the rates had dropped to 30% and 26%, respectively, by 36 months (data not shown). Similarly, we previously found in these data that symptoms of mental disorders also declined over time (

9), suggesting that the need for mental health services would also have declined.

However, our data showed that relatively few participants obtained substance abuse services, suggesting that many of the changes in drug use may have occurred without specialty treatment. We have previously found significant variation among sites in substance abuse treatment as well as in perceived need for treatment (

1). This finding may be associated with the fact that the state with the lowest treatment rate is also the one with the longest travel distance for available services (data not shown). We suspect that the greater use of mental health services may be partly accounted for by the urgencies of mental health issues, such as depression, which may be more compelling than those arising from substance abuse or dependence, but these differences require further research. Data from the 2006 NSDUH (

11) also found substantially more treatment seeking for mental than for substance use disorders (39.6% versus 2.8%) by persons with substance use disorders and serious psychological distress.

Study attrition was greatest for younger individuals, whites, males, unmarried individuals, and those with higher incomes, but we found little evidence of differences in severity of substance abuse (

9). Prior research with this sample found no association between age, race, gender, and treatment seeking for substance abuse (

1).

Conclusions

These analyses did not tell us which participants were more likely to receive mental health compared with substance abuse services, and analysis of this issue is ongoing. Subsequent analysis will explore potential predictors of the trajectories. Overall, we know much more about use of substance abuse services by substance users (

1,

2) than we know about their use of mental health services, and future work is needed to better understand the extent of help seeking for mental health services in this frequently comorbid population.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants R01 DA15363 and R01 DA14340.

The authors report no competing interests.