The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recently affirmed that routine screening for depressive disorders and alcohol misuse in primary care settings is an important mechanism for reducing morbidity and mortality (

1,

2). In addition, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) requires regular screening for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) because it is the mental disorder most commonly associated with combat (

3). The USPSTF makes clear that screening is valuable only when assessment, treatment, and monitoring are available; indeed, the utility of screening is unclear if a positive result does not consistently spur an appropriate clinical action. This may mean a brief intervention in primary care or referral to specialty care; in either case, USPSTF guidelines suggest that integrated care management can improve effectiveness (

1,

2).

Veterans at the Philadelphia VA Medical Center (PVAMC) are screened annually for depressive disorders, alcohol misuse, and PTSD. For patients who screen positive on one of these validated screens, providers are electronically prompted to offer one of three options for additional clinical services: referral to the Behavioral Health Laboratory (BHL), an integrated care program to facilitate further assessment and brief intervention in the primary care setting; referral to a specialty addictions service; or emergency care.

The BHL is a telephone-based clinical service that is fully integrated within primary care and has been in use since 2003. It builds upon the Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment initiative promoted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration for screening of individuals with or at risk of substance-related problems (

4). It provides primary care clinicians with behavioral health triage assessment and treatment decision support; symptom monitoring; care management of depression, anxiety, and alcohol misuse; and enhanced referral to specialty care (

5).

This cross-sectional retrospective study was conducted to help assess the degree to which behavioral health screening in primary care results in referral for additional clinical services and whether referral rates differ by screening instrument.

Methods

Within VA medical centers, annual screening for alcohol misuse, depression, and PTSD is prompted for all patients by the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). Although these screens may be conducted by any provider, this analysis focused on those performed by primary care clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) at PVAMC and affiliated community-based outpatient clinics from January 2008 through March 2010. The project was reviewed by the VA Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt from requiring consent because the data collected were part of routine clinical practice. Alcohol misuse is evaluated with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) (

6), depression is assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) (

7), and PTSD is assessed with the Primary Care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD) (

8). The provider asks questions as prompted by CPRS, which then scores the patient's responses to determine whether the screen is positive. This project analyzed dispositions after positive screens for alcohol misuse (AUDIT-C ≥5), depressive disorders (PHQ-2 ≥3), and PTSD (PC-PTSD ≥3).

Primary care clinicians were included in the analysis if there were at least five positive screens among their patients for alcohol misuse or depressive disorder, yielding a total of 42 physicians and 35 nurse practitioners or physician assistants who provided screens from their patients for analysis. Screens from patients already in specialized behavioral health treatment for at least one of the three conditions were excluded. After patients received a positive screen, providers could offer additional clinical services as outlined above. A positive screen could result in no additional clinical services if the patient refused them or, in the case of alcohol misuse, if the provider deemed the drinking to be within safe limits (“Patient drinking within safe limits, no further assessment required”). However, all providers who had a patient with a positive AUDIT-C screen were prompted to offer a brief intervention and advise the patient “about recommended limits and to drink below them” (with suggested drink limits indicated in the software), as well as to review associated medical problems.

A mixed-effects binomial logistic regression model was run to predict the probability of referral to additional clinical services (coded 0, no additional clinical services, or 1, additional services) after a positive screen as a function of screen type, provider type (physician, or nurse practitioner or physician assistant), and location (PVAMC or VA community-based outpatient clinic).The mixed-effects model adjusted for clustering of observations at the provider level. Specifically, provider was modeled as a random effect, and all other variables were modeled as fixed effects.

Results

A total of 10,217 positive screens were completed over the two-year period, including 1,994 for PTSD, 3,396 for depression, and 4,827 for alcohol misuse. Of these screens, 1,165 patients were already in specialty behavioral health care for at least one of the conditions, leaving 9,052 veterans eligible for additional clinical services after their positive screen. The mean±SD age of eligible veterans was 59.0±16.2, and they were primarily male (N=8,418 of 9,052, 93%). Data on race were not available for the full sample. Of the 2,772 veterans with a positive screen for depression, 1,693 (61%) were referred to additional clinical services: 1,427 (52% of positive screens) to the BHL, 251 (9%) to a specialist, and 15 (<1%) to urgent care. Of 1,590 patients with a positive PTSD screen, 1,170 (74%) received referrals: 920 (58%) to BHL, 239 (15%) to a specialist, and 11 (1%) to urgent care. Of the 4,690 patients who screened positive for alcohol misuse, 686 (15%) were referred to additional services: 616 (13%) to BHL and 70 (2%) to a specialist. Providers reported that 2,958 (63%) were drinking within safe limits and that 1,046 (22%) refused additional services.

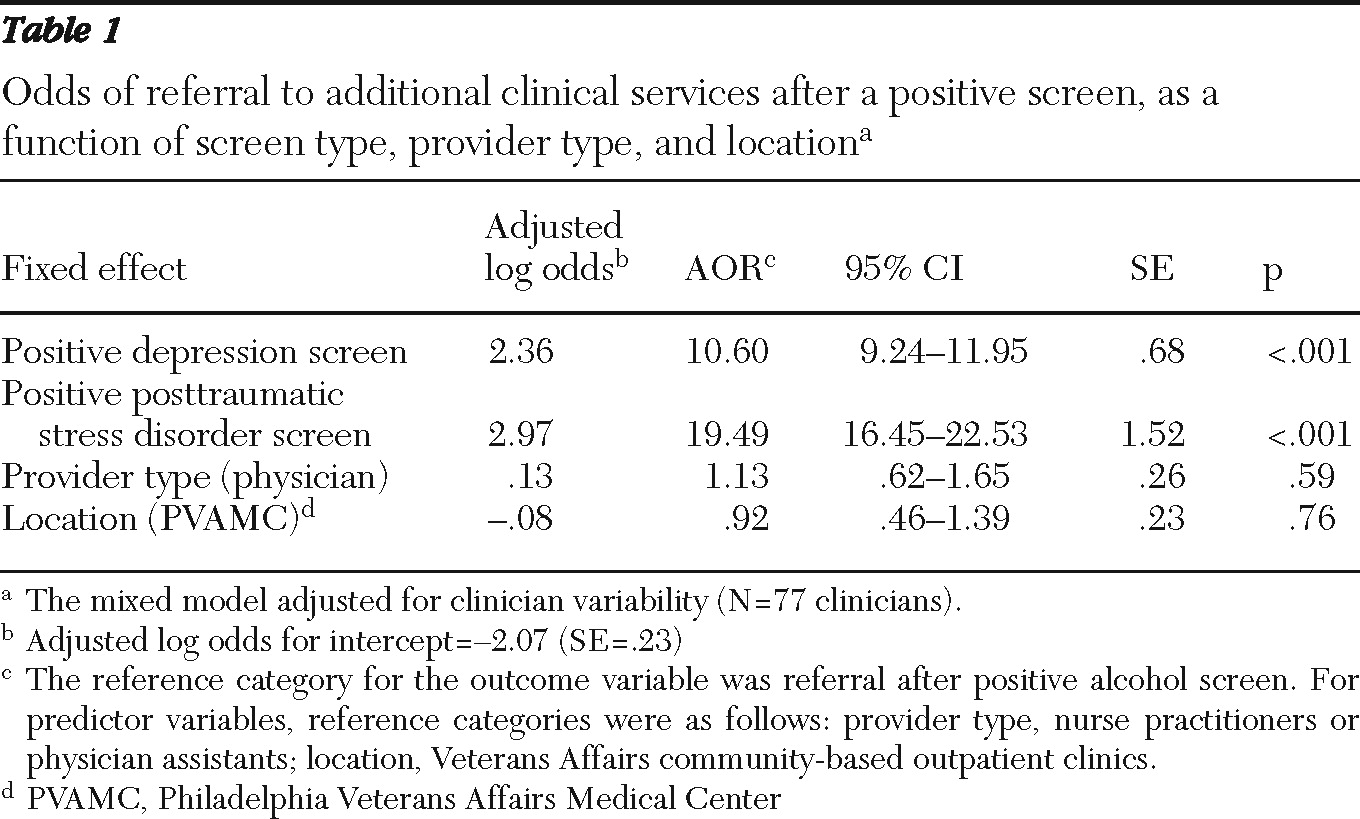

Results of the mixed-effects logistic regression are shown in

Table 1. With adjustment for provider type, location, and provider-level clustering of observations, patients with a positive depression screen were 10.60 times more likely to be referred for additional services than those with a positive alcohol screen. Patients with a positive PTSD screen were 19.49 times more likely to be referred for additional services than patients with a positive alcohol screen. Neither provider type nor location was a significant predictor of referral.

Discussion

Screens are an important tool in primary care to help lower morbidity and mortality from a variety of conditions. For this reason, primary care clinicians within the VA are prompted to screen annually for depression, alcohol misuse, and PTSD. Our analysis demonstrated that most patients with a positive depression or PTSD screen were referred for additional clinical services; in contrast, only 15% of those with a positive alcohol misuse screen were referred. Compared with a positive alcohol misuse screen, a positive depression or PTSD screen had nearly 11 or 20 times greater odds, respectively, of resulting in referral to additional services. The sample, albeit large, came from an urban medical center and affiliated suburban sites serving predominantly male veterans. As such, it is not possible to generalize the results to nonveterans or to women.

The explanation for the much lower alcohol misuse referral rate is unclear. All three screening instruments and the BHL had been in use for years before the study period, with numerous educational efforts to enhance provider comfort. That providers deemed 63% of patients with positive screens to be drinking “within safe limits” suggests that providers believed the threshold for a positive alcohol misuse screen was too low relative to depression and PTSD screens, deciding that a positive screen was in fact a false positive. However, at cutoff values used, the positive likelihood ratio is 6.95 for AUDIT-C (for heavy drinking, abuse, or dependence) (

6), 1.8 for PC-PTSD (

8), and 5.4 for PHQ-2 (

7). Therefore, a positive screen on the AUDIT-C magnifies the pretest probability of clinically significant alcohol misuse more than either of the other screens, yet it resulted in significantly lower odds of referral. In addition to ongoing institutional efforts to educate providers regarding the instruments, the correlation between the AUDIT-C score (automatically generated by CPRS based on patient response rather than calculated by the clinician) and misuse was explicitly stated in the results of the screen (“positive … with score of 5 or above”).

Perhaps providers believed that positive screens picked up true alcohol misuse but preferred to address it through their own brief intervention rather than utilize available care management. Unfortunately, we are unable to comment on the rate of such brief interventions (or on rates of patient refusal of additional services) because this would have required a chart review, which even if conducted might not have accurately documented what was discussed. If such interventions frequently occur, this would be in contrast to a study by Tracy and colleagues (

9), who surveyed VA providers and found that most (59%) refer patients to specialty treatment programs; those who reported providing ongoing counseling did so for less than 1% of their patient caseload. Lastly, providers may have felt that the services available for alcohol misuse are less effective than those for PTSD or depression, therefore referring fewer patients with positive alcoholmisuse screens out of a sense of therapeutic pessimism. Given high rates of medical comorbidity among those with alcohol misuse, lack of follow-up services suggests missed opportunities for preventive care.

The value of any system of screening is unclear if a positive screen does not consistently result in appropriate action. Facilities that offer integrated care management for alcohol misuse may need to establish mechanisms to ensure greater referral rates from positive screens for alcohol misuse, such as more regular and effective provider education. A more aggressive option would be to utilize a default referral in the case of a positive screen (

10), such as automatic referral to BHL in this population.

Conclusions

Screening for alcohol misuse, depression, and PTSD in primary care provides an important opportunity for intervention that can lead to less morbidity and mortality from these conditions. Primary care clinicians perform a large volume of screens, but the odds of referral to additional clinical services were significantly lower for a positive alcohol misuse screen than for positive screens for depression or PTSD. Facilities offering integrated primary care and mental health services may consider strategies such as provider education or default referrals to promote greater referral rates and realize the potential benefit to patients afforded by screening.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Maust is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health-Clinical Research Scholars Program of the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania. The authors thank Kevin Lynch, Ph.D., and Caroline McKay, Ph.D., for their assistance with the statistical analysis.

The authors report no competing interests.