In contrast to other mental disorders for which treatment disparities have been convincingly demonstrated (

1–

5), no national studies have examined treatment disparities for schizophrenia, even though regional studies have reported large variations in treatment (

6–

8). This study investigated differences in antipsychotic medication management and hospitalization by age, gender, race-ethnicity, insurance, rurality, and region and controlled for available indicators of clinical severity in a nationally representative sample of outpatient visits made from 1999 through 2007 by patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Methods

Sample

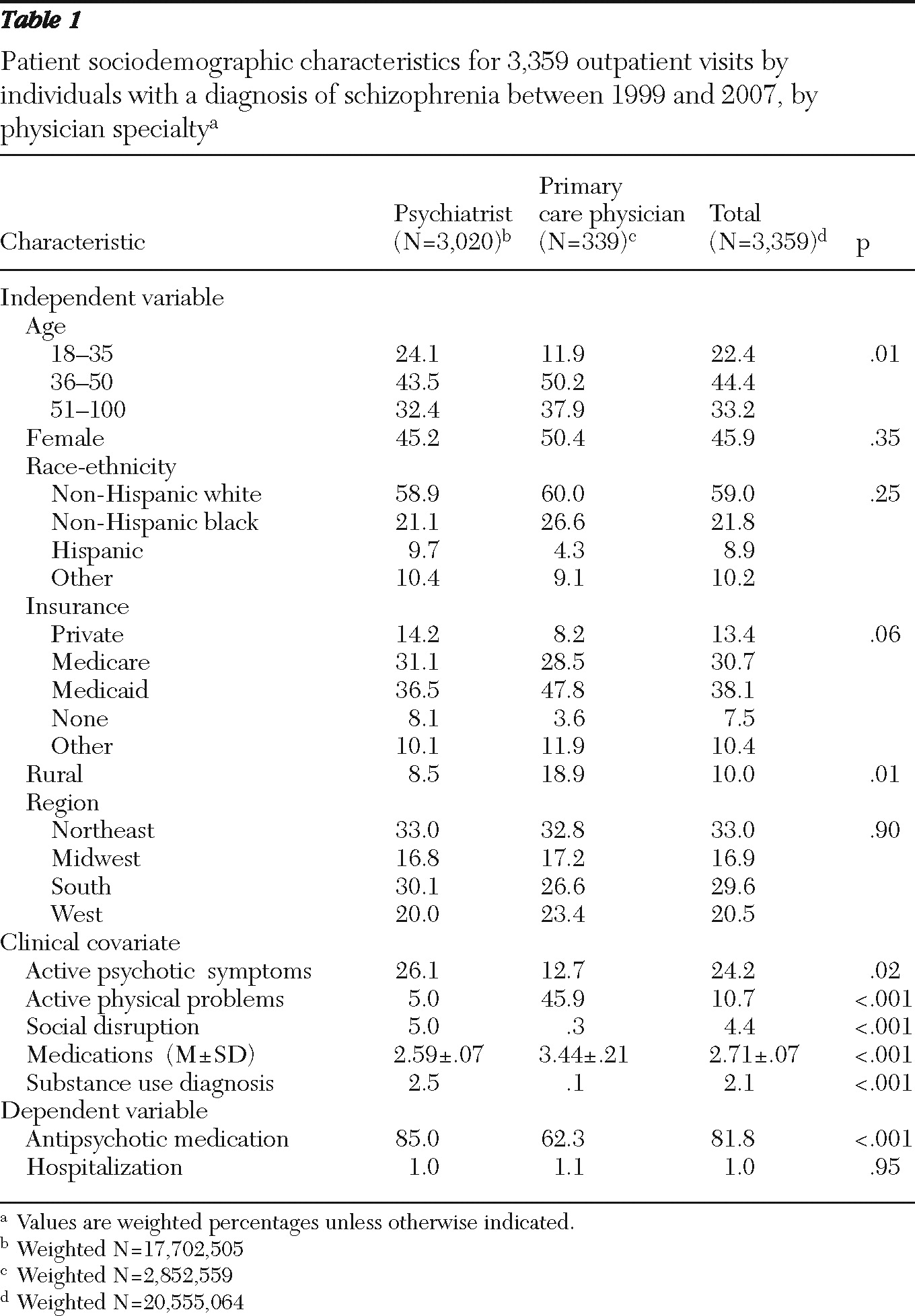

We conducted a secondary analysis of office visit forms collected in the 1999–2007 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS). NAMCS produces an annual national probability sample of visits to physicians who provide outpatient care in freestanding, office-based practices, including health maintenance organizations and nonfederal government clinics. During the nine years (1999–2007), physician participation rates averaged 64.3%, ranging from a low of 58.9% in 2005 to a high of 67.7% in 2000. NHAMCS produces an annual national probability sample of visits to physicians who provide outpatient care in nonfederal general and short-stay hospitals. During the nine years, NHAMCS sampled between 458 and 546 hospitals each year. Of the sampled hospitals, 391 to 462 hospitals were eligible to participate in the survey. Annual response rates ranged from 89.4% to 96.0%. Physicians complete a standardized office visit form for each sampled visit. The form contains detailed information, including up to three patient reasons for the visit, up to three physician diagnoses based on ICD-9, medications and other treatment provided, and visit disposition, including whether the patient was hospitalized.

For the study reported here, NAMCS and NHAMCS data files were combined in accordance with directions for analysis provided by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (

9). The study sample included all visits made by patients aged 18 and older to psychiatrists and primary care physicians (family physicians, general internists, or general practitioners) in which schizophrenia (

ICD-9 code 295.XX) was listed as one of the three physician diagnoses. The 120 (unweighted) visits to physician assistants and nurse practitioners could not be included because we could not determine whether these providers worked in states that gave them prescribing privileges. The NCHS Institutional Review Board approved the data collection protocol, including a waiver of the requirement for informed consent of participating patients. The Florida State University Institutional Review Board approved the analysis.

Operational definition of major constructs

Independent variables.

Age was defined in tertiles (18–35, 36–50, and 51–100 years) to examine nonlinear relationships. Gender was defined as female or male. Race-ethnicity was defined as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other. For the insurance variable, the primary expected source of payment for the visit was defined as private, Medicare, Medicaid, none, and other (

10). Rurality was defined by nonmetropolitan statistical area (rural) or metropolitan statistical area (urban) (

11) to capture differential access to specialty care (

12). Region was coded as Northeast, Midwest, South, or West; state mental health spending per capita differs across regions (

13).

Dependent variables.

Management of antipsychotic medication (aripiprazole, chlorpromazine, clozapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, loxapine, mesoridazine, molindone, olanzapine, paliperidone, perphenazine, promazine, quetiapine, risperidone, thioridazine, thiothixene, trifluoperazine, and ziprasidone) was defined as physician notation of medications prescribed, ordered, supplied, administered, or continued at the visit. The wording of the item did not allow us to definitively differentiate patients who did or did not take any antipsychotic medication. Visits characterized as not involving antipsychotic medication management identified patients who currently had no prescription for any antipsychotic medication from any provider as well as patients who were currently taking an antipsychotic medication prescribed by this or another provider that did not require a refill or adjustment at the visit. No data on dosage were available. Hospitalization was defined as a notation by the physician in the visit disposition section that the patient was hospitalized after the visit. No data on psychiatric versus medical hospitalization were available.

Available clinical covariates

An active psychotic symptom was defined as a physician notation that one of up to three reasons for the visit included delusions or hallucinations, functional or organic psychoses, or speech or sense disturbances not including paresthesias. An active physical problem was defined as a physician notation that one of up to three reasons for the visit included one of 198 physical symptoms, diagnoses, or treatments. Medications was defined as the total number of psychotropic and nonpsychotropic medications (other than antipsychotic medication) prescribed, ordered, supplied, administered, or continued during the visit. Social disruption was defined as a physician notation that one of up to three reasons for the visit included violence, hostility, temper, hysteria, marital strife, family difficulties, or police or legal problems. Substance use diagnosis was defined as physician notation that one of up to three diagnoses for the visit was an alcohol or drug problem. Physician specialty was categorized as psychiatrist or primary care physician (general internist, family physician, or general practitioner).

Analyses

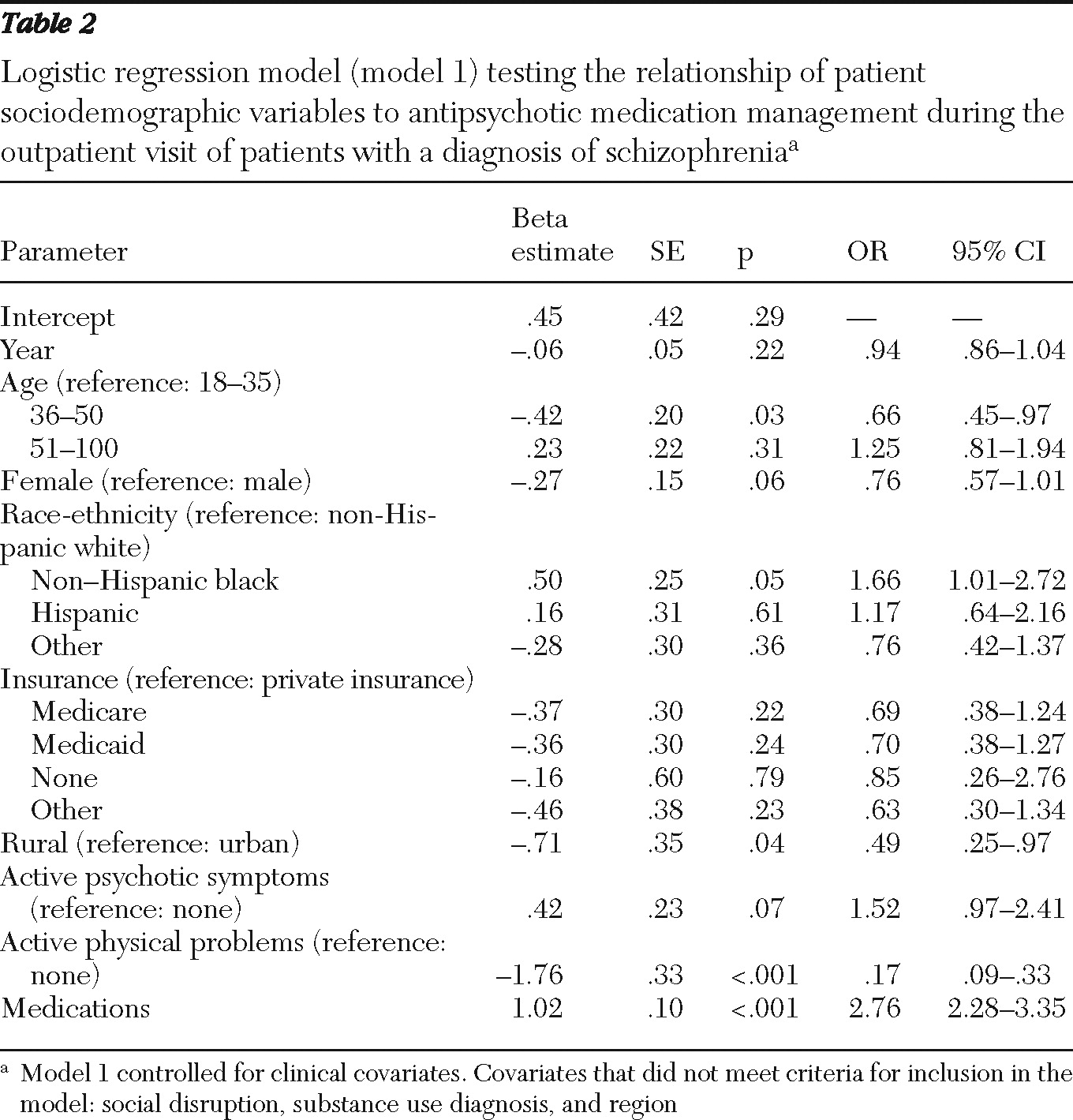

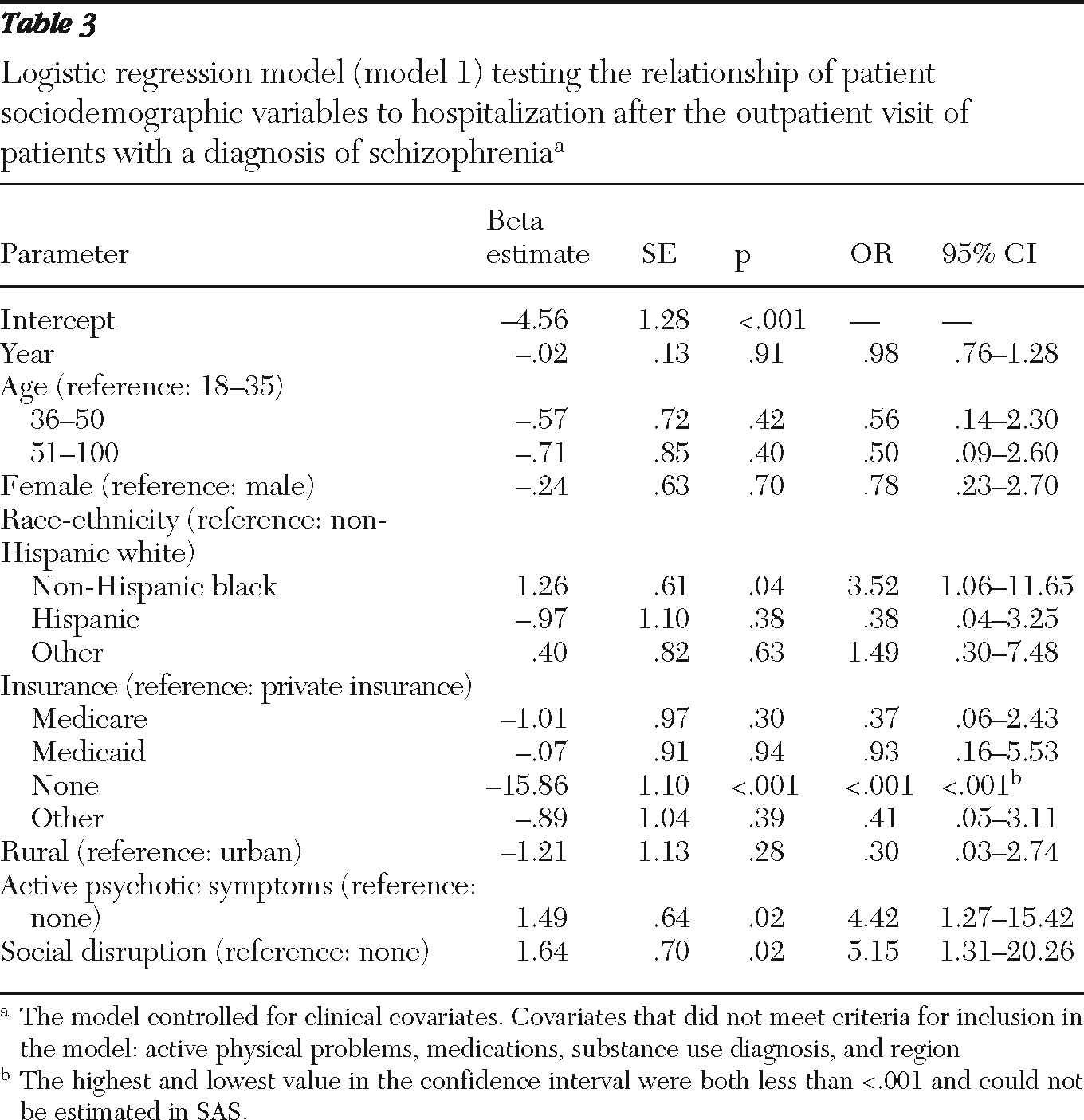

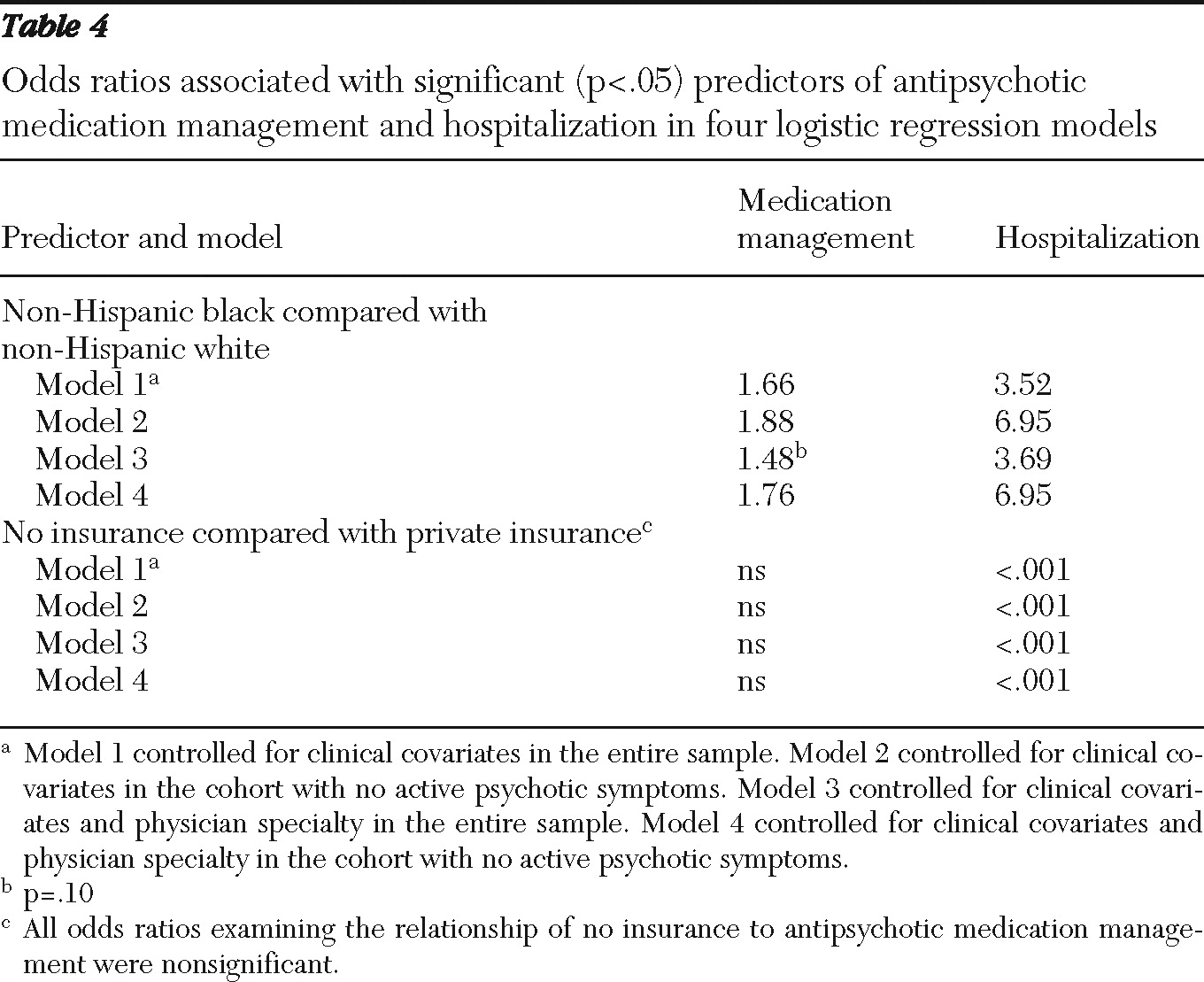

We used four logistic regression models to test the relationship of sociodemographic variables to antipsychotic medication management and hospitalization. Model 1 was conducted for the entire cohort and controlled for clinical covariates. Model 2 was conducted for the cohort with no psychotic symptoms and controlled for clinical covariates. Model 3 was conducted for the entire cohort and controlled for clinical covariates and physician specialty. Model 4 was conducted for the cohort with no psychotic symptoms and controlled for clinical covariates and physician specialty. We tested sociodemographic predictors in the entire cohort and in the cohort with no active psychotic symptoms to determine whether the same disparities could be observed in the clinically heterogeneous sample (entire cohort) and the clinically homogeneous sample (cohort with no active psychotic symptoms) to reduce concerns about treatment differences arising from unobserved clinical variation. We tested sociodemographic predictors in models that did and did not control for physician specialty to differentiate disparities in the current health care system (in which sociodemographic groups differ in the probability of specialty care treatment) from disparities in some future health care system (in which sociodemographic groups do not differ in the probability of specialty care treatment).

Using weights to account for selection probability, nonresponse, and other factors necessary to characterize a national sample of schizophrenia visits in the United States during the nine-year period, each logistic regression was adjusted for clinical covariates that predicted the dependent variable at the p<.2 level in univariate analyses. Each model also included survey year, which was coded as a linear variable after preliminary investigation identified no quadratic trends in any dependent variable by time. We present model 1 findings in the tables because this model produced the most generalizable findings on potential disparities in the current health care delivery system. Significant sociodemographic predictors in the other three models are presented in the Results section to allow readers to compare the consistency of findings in clinically heterogeneous and homogeneous populations (model 1 compared with model 2, and model 3 compared with model 4) and in the current health care system and in some future health care system in which sociodemographic subgroups are equally likely to receive specialty care (model 1 compared with model 3, and model 2 compared with model 4).

Discussion

The study found that psychiatrists provided 86% of visits to patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and that 85% of the psychiatrist visits involved antipsychotic medication. Primary care physicians provided the remaining 14% of visits, and 62% of those visits involved antipsychotic medication. Primary care physicians and psychiatrists reported virtually identical hospitalization rates after a visit by a patient with a schizophrenia diagnosis (1%).

These findings provide evidence of potential disparities in the delivery of care for U.S. outpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. In at least three of the four models tested, we observed consistent differences by race-ethnicity in antipsychotic medication management and hospitalization and differences in hospitalization by insurance. The fact that these patterns appeared in both clinically heterogeneous and homogeneous groups suggests that our findings are not attributable to unobserved differences in clinical severity. In addition, the fact that these differences appeared in models controlling for physician specialty suggests that our findings are not attributable to differences in the probability of specialty care. No disparities in antipsychotic medication management and hospitalization were consistently observed by age, gender, rurality, and region.

Although multiple studies have examined race-ethnicity disparities in the prescription of first- versus second-generation antipsychotic medication (

14–

19), our study is the first national study to examine potential disparities in antipsychotic medication management. Our race-ethnicity findings differ from the results of the only other study of this question, which reported no racial differences in a regional sample of Medicaid recipients with schizophrenia who had not been recently hospitalized (

20). It is not possible to determine whether the discrepant findings between the two studies are the result of differences in samples, operational definitions, or statistical modeling. The increased odds of antipsychotic medication management for non-Hispanic blacks may indicate that they are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to receive any antipsychotic medication. However, we suspect that the race-ethnicity differences indicate that physicians of non-Hispanic blacks were more likely to adjust their antipsychotic medications during the visit because the previously prescribed drug had serious side effects or could not be adhered to (

1). The latter explanation is consistent with the odds of increased hospitalization that we observed for non-Hispanic blacks.

Our study is also the first national study to examine potential disparities in hospitalization, and our findings replicated regional findings for non-Hispanic blacks (

21,

22) and the uninsured (

23,

24). The consistencies between national and regional findings are encouraging because regional studies are often conducted in databases with a broader range of clinical covariates. The increased odds of hospitalization for non-Hispanic blacks suggests that blacks may not get high-quality outpatient care, that they lack the psychosocial support in the community needed to prevent hospitalization, or that clinicians view black patients as more dangerous and adopt a lower threshold for hospitalization (

1). The decreased odds of hospitalization for noninsured patients suggest that these patients may be hospitalized too infrequently or that privately insured patients may be hospitalized too often, even in systems that are highly managed. Further research is needed to determine reasons for the relationships we observed.

The internal and external validity of our findings is subject to the following considerations. First, the diagnostic accuracy of our sample was imperfect because the diagnoses relied on physician judgment rather than on objective assessment tools. Although policy analysts find it useful to generalize to patients who receive real-world diagnoses, this potential measurement error is problematic if diagnostic accuracy differed by the sociodemographic characteristics that we examined. Second, the database does not contain a comprehensive set of clinical covariates. Although further research in databases with more comprehensive clinical covariates is definitely warranted, it is encouraging that we were able to replicate our major findings for visits by patients with no active psychotic symptoms—a clinically more homogeneous population. Third, the database does not systematically sample visits in which patients with schizophrenia receive psychosocial treatment. Although smaller studies have found disparities in receipt of psychosocial treatment by age, race-ethnicity, and rurality (

25,

26), we cannot comment on potential national disparities for this important source of evidence-based care except to note that patients who obtain mental health care exclusively in primary care settings may be less likely to receive this important treatment. Fourth, because the unit of analysis is a single office visit, patients making frequent visits because of illness severity may be overrepresented; however, given that each office sampled visits for a four-week period only, this source of measurement error is not likely to greatly bias findings. Even with these limitations, the database represents the most comprehensive national survey of office-based physician visits for schizophrenia over geography, population, and time.