People with diabetes and co-occurring behavioral disorders, which include depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders, have been observed to have poorer clinical outcomes than those without behavioral disorders. In a cross-sectional study, Black (

1) reported that compared with people with diabetes alone, people with diabetes and comorbid depression had higher odds of having vascular diseases, eye problems, kidney disease, and hospitalizations. In a study using administrative data from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in 1998, Krein and colleagues (

2) showed that people with diabetes and serious mental disorders (schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) were more than twice as likely as those with diabetes alone to be hospitalized for diabetes treatment. Further, Fortney and colleagues (

3) analyzed hospitalization records from the VA between 1991 and 1995 and observed that people with diabetes, depression, and alcohol use disorder had longer hospital stays than people with diabetes alone had. Those with all three conditions averaged 200.4 total hospitalization days during the study period, people with diabetes and depression averaged 154.7 total hospitalization days, and people with diabetes and alcohol use disorder averaged 125.3 total hospitalization days, compared with an average of 75.9 total hospitalization days for people with diabetes alone.

However, no studies have compared diabetes-related clinical outcomes, such as diabetes-related complications and hospitalizations, across different mental disorder categories, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression and anxiety. In addition, beneficiaries of Medicare, Medicaid, or both programs, a population in which rates of diabetes and of behavioral disorders are particularly high, have not been included in previous investigations of diabetes outcomes. Therefore, further research is needed to understand the relationships between behavioral disorders and diabetes outcomes in these populations with publicly sponsored health care coverage.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between behavioral disorders and clinical outcomes of diabetes. First, diabetes outcomes, such as eye complications, diabetic neuropathy, diabetic nephropathy, cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, lower-limb amputations, and diabetes-related hospitalizations, were compared across behavioral disorder diagnosis groups. Multivariate analyses were performed to determine associations between specific behavioral disorders and clinical outcomes of diabetes, with adjustment for potential confounders.

Methods

Study design and data

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using individual-level administrative data from the Medicare and Medicaid populations in Massachusetts. Medicare and Medicaid claims data were collected for Massachusetts residents in calendar years (CY) 2004 and 2005. The Medicare data used in this study came from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the form of research identifiable files; the Medicaid data were obtained from the Massachusetts Medicaid Management Information System. The study was part of a larger analysis of treatment, service use, and expenditures for beneficiaries with behavioral disorders. Socioeconomic status data for beneficiaries' zip code-based community, median household income in 1999, and percentage of high school graduates were obtained from Census 2000. This study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board.

Selection criteria

We included beneficiaries who were at least 18 years old as of January 1, 2004. The study population was characterized according to their Medicare and Medicaid coverage. The Medicare-only group included beneficiaries who were enrolled in Parts A and B for at least ten months during both CY 2004 and 2005 and who were not enrolled in Medicaid. Beneficiaries with Medicaid only were enrolled in Medicaid for at least ten months during both years with no Medicare enrollment. Dually eligible beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare Part A and Medicaid for at least ten months during both years. The purpose of the length-of-enrollment requirement was to ensure that the study population had stable and continuous health coverage. Beneficiaries with Medicare Advantage or who were residing in nursing homes for 90 days or more were excluded from the analysis.

All beneficiaries with type 2 diabetes were selected. They were identified by either one ICD-9-CM diagnosis on an inpatient claim or diagnoses on two outpatient claims (ICD-9-CM codes 250.xx, 357.2, 362.0, 362.01, 362.02, 366.41, and 648.0) in CY 2004. We could not link 2,263 individuals to a census area, and they were thus excluded from the study. As a result, the study included 106,174 individuals.

Identification and classification of behavioral disorders

Behavioral disorders were identified by any one inpatient ICD-9-CM diagnosis or any two outpatient diagnoses in CY 2004. Mental disorders included schizophrenia and paranoid states (codes 295.x and 297.x), bipolar disorder (296.0, 296.1, and 296.4–296.7), depression or anxiety (codes 296.2, 296.3, 298.0, 300.01, 300.02, 300.4, 309.0, 309.1, 309.81, and 311.x), and other mental disorders (codes 298.1–298.4, 298.8–298.9, 300.1, 300.2, 300.3, 300.5–300.9, 301.x, 302.x, 306.x–308.x, 309.2–309.4, 309.82, 309.83, 309.89, 309.9, and 312.x–316.x). Mental disorders were categorized hierarchically, and individuals with more than one diagnosis were classified according to their most serious diagnosis. Schizophrenia or paranoid states were ranked as most serious, followed by bipolar disorder, then depressive or anxiety disorders, and finally other mental disorders. Individuals without any mental disorder diagnoses were the reference group. For example, an individual with diagnoses of schizophrenia and depression would be categorized in the schizophrenia and paranoid disorders group. Someone with bipolar disorder and depression would be categorized in the bipolar group.

Substance use disorders included alcohol abuse and dependence (codes 291.x, 303.x, 305.0, and 571.0–571.3) and drug abuse and dependence (codes 292.x, 304.x, 305.2–305.9, and 648.3). The reference group for any alcohol use disorder consisted of individuals without an alcohol use disorder, and the reference group was similarly constructed for any drug use disorder. A summary variable, any behavioral disorders, was created to indicate beneficiaries with any type of mental disorder or substance use disorder for the adjusted analyses (reference group: beneficiaries without any behavioral disorders).

Assessment of diabetes-related outcomes

Using ICD-9-CM and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, diabetes-related complications were identified from one inpatient or two outpatient claims during CY 2005 from the following categories: eye complications (ICD-9-CM codes 250.5 and 362.0), nephropathy (ICD-9-CM code 250.4), ischemic heart disease (ICD-9-CM codes 410–414), cerebrovascular disease (ICD-9-CM codes 431–436 and v1254), neuropathy (ICD-9-CM code 250.6), and lower-limb amputations (ICD-9-CM codes 250.8 and v497; CPT codes 27880, 27882, 27886, 28800, 28805, 28810, 28820, and 28825). The outcomes were analyzed separately and as a single measure (any complications). Diabetes-related hospitalization was assessed by any inpatient claims with any diabetes-related ICD-9-CM code—that is, diabetes and its complications—as the principal diagnosis.

Other covariates

Covariates included in the study came from two sources: the combined Medicare and Medicaid data and the Census 2000 data. The following variables were obtained from the Medicare and Medicaid data set: gender, race-ethnicity (whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and others), age, physical illness burden (represented by the Chronic Illness and Disability Payment System, CDPS [

4]), preexisting diabetes-related complications (eye complications, nephropathy, neuropathy, lower-limb amputations, ischemic heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease) identified by

ICD-9-CM codes, types of health coverage (Medicare only, Medicaid only, and dual eligibility), and frequency of physician visits. The CDPS was originally designed to allow the Medicaid program to predict health care expenditures for beneficiaries with

ICD-9-CM-based diagnoses by assigning weights to diagnoses according to their expected use of resources (

4). Therefore, a modified version of the CDPS score was used to approximate the severity of comorbid conditions by assigning more weights to more costly diseases, which are usually more severe. In estimating the CDPS scores, we omitted behavioral diagnoses from the assessment so that the measure represented physical illnesses only. Median household income and percentage of high school graduates in beneficiaries' zip code-based residential communities were obtained from Census 2000 data as proxy measures of the beneficiaries' socioeconomic status.

Statistical analysis

Unadjusted analyses were performed with chi square tests to compare the distributions of outcomes across behavioral disorder categories. We used logistic regressions to examine the associations between behavioral disorders on diabetes-related outcomes, adjusting for covariates. Two logistic models, one with the summary measure of any behavioral disorders and one with specific behavioral disorders, were performed to estimate the associations between adverse diabetes outcomes and any or specific behavioral disorders, respectively. Because treatment is likely to vary by practice or by provider and we were unable to identify specific providers across Medicaid and Medicare claims, we used Hospital Service Areas as a clustering variable to approximate small-area variations in care (

5). We included robust variance estimates in the model to account for correlations in the patterns of care among patients within Hospital Service Areas (

5). In these regression models, different population selection criteria were applied. Individuals with a particular previous complication were excluded from the analyses of the same complication as outcome. For example, people with previous eye complications (in 2004) were excluded from the analysis of eye complications as a 2005 outcome. No individuals were excluded from analyses of any diabetes complications and diabetes-related hospitalizations as outcomes. In adjusted analyses, age was categorized into four groups—younger than 55, 55–64, 65–74, and 75 and older—and CDPS scores were divided into quartiles. Levels of statistical significance were set at

α=.05 for unadjusted analyses and adjusted analyses of any diabetes-related hospitalizations and at

α=.01 for adjusted analyses of individual diabetes complication to adjust for the effects of multiple comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata, version 10.

Results

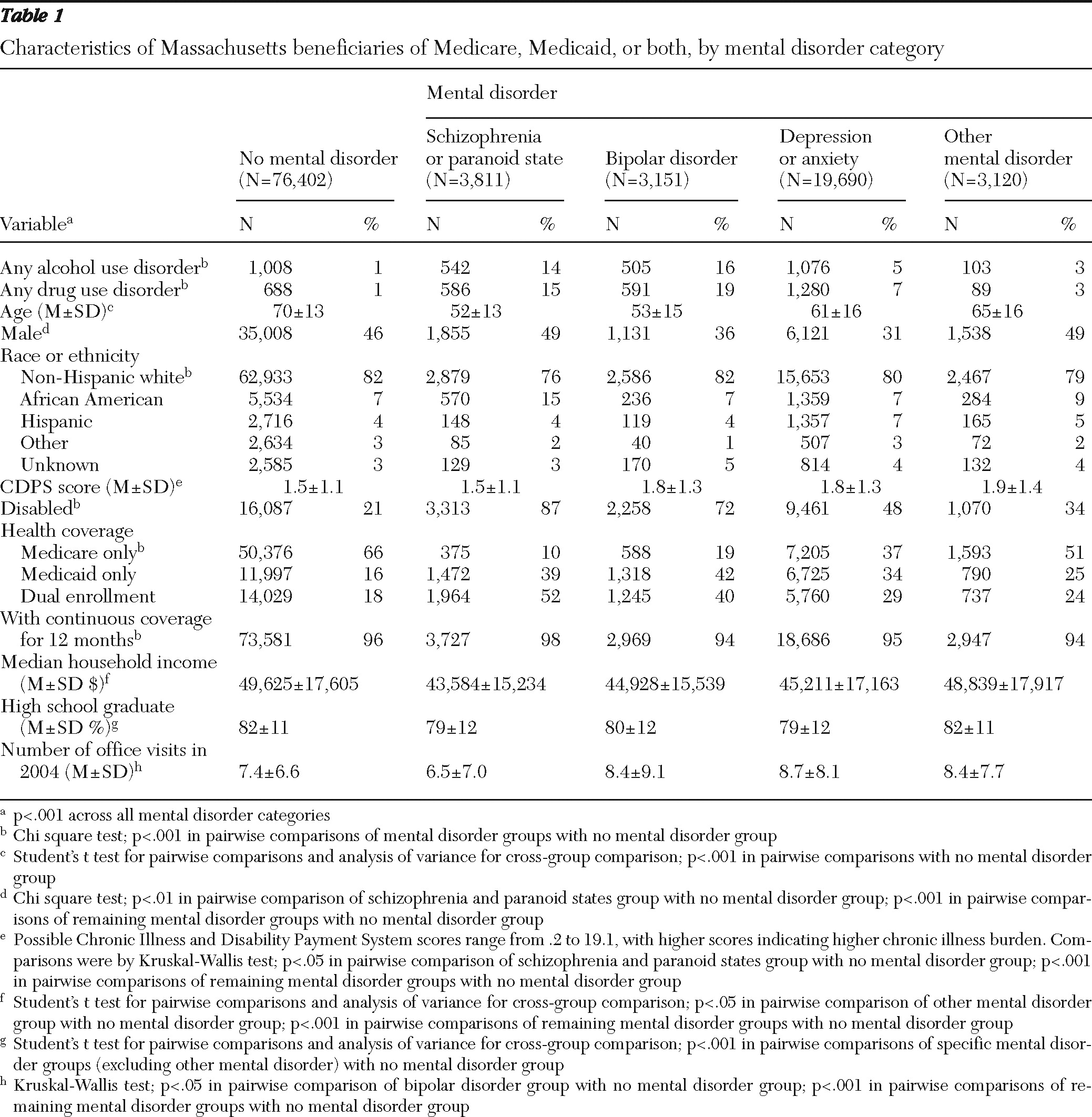

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the study population, and characteristics by prevalent adverse diabetes outcomes are shown in

Table 2. In general, beneficiaries with any mental disorders were significantly younger than those with no mental disorders (mean age range of 52–65 compared with 70±13; p<.001).

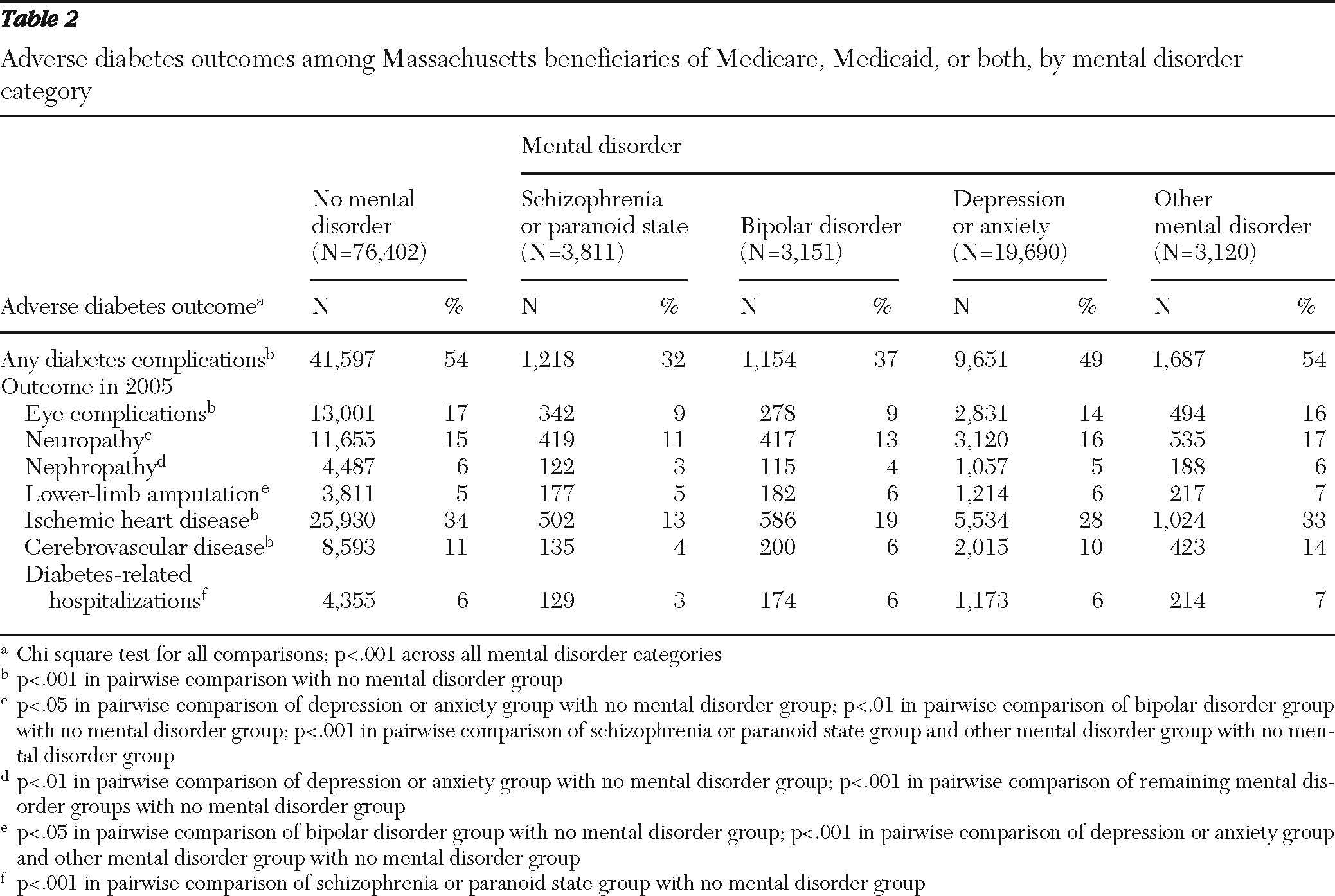

Overall rates of any diabetes complications were lower among beneficiaries with schizophrenia or paranoid states (32%), bipolar disorder (37%), or depression or anxiety (49%) than among those with no mental disorders (54%). Compared with beneficiaries with no mental disorders (17%), the rates of eye complications in 2005 were lower among beneficiaries with schizophrenia or paranoid states (9%), bipolar disorder (9%), depression or anxiety (14%), and other mental disorders (16%) (p<.001). Similar patterns were noted in the rates of ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease in 2005. However, there were instances where beneficiaries with mental disorders had higher rates of diabetes complications. For example, the rates of neuropathy in 2005 were significantly higher among beneficiaries with depression or anxiety (16%, p<.05) and other mental disorders (17%, p<.001) than among those with no mental disorders (15%).

The results from adjusted analyses are presented in

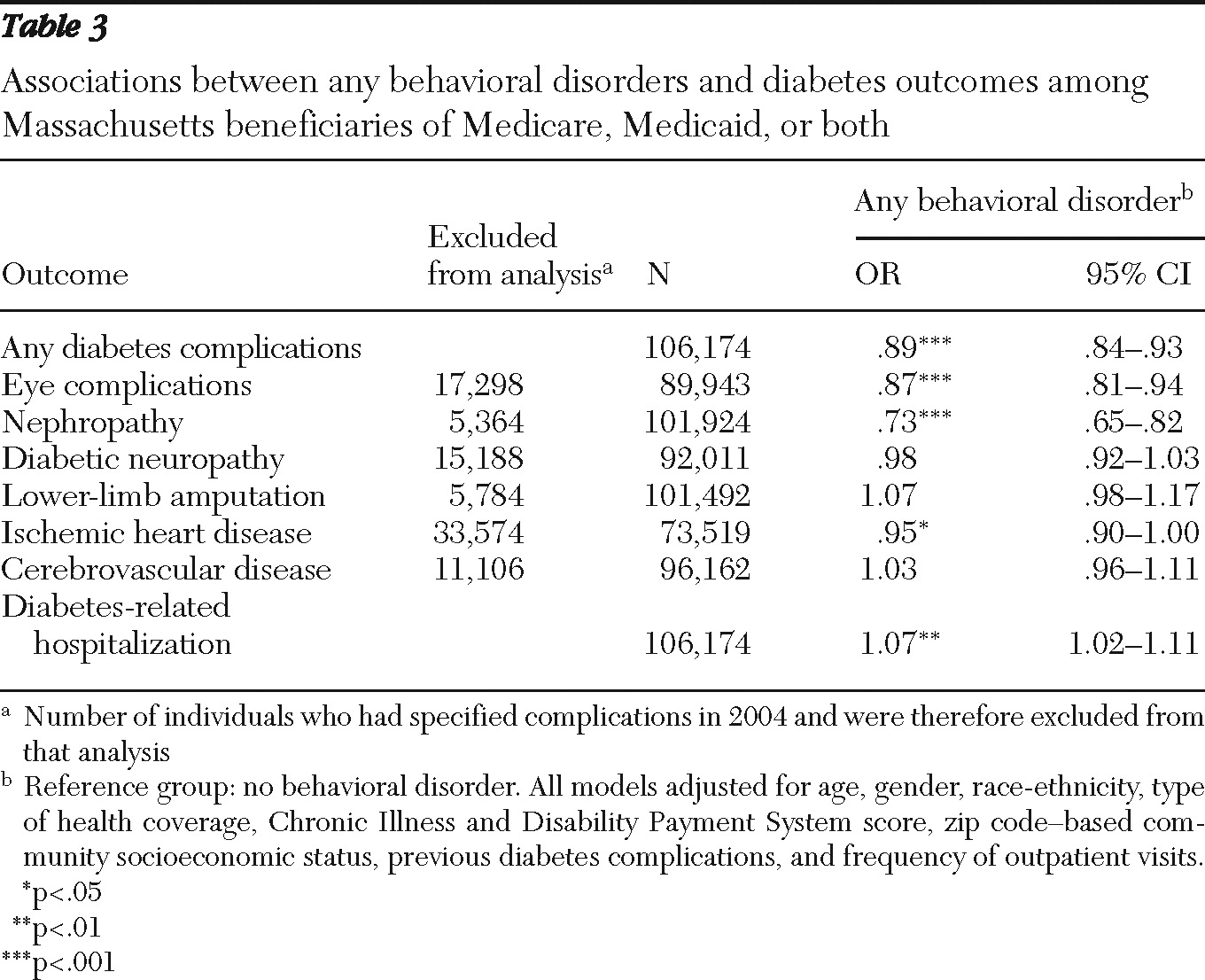

Tables 3 and

4. Overall, the presence of any behavioral disorders was associated with lower likelihood of new cases of any diabetes complications (odds ratio [OR]=.89), eye complications (OR=.87), and nephropathy (OR=.73) but higher likelihood of diabetes-related hospitalizations (OR=1.07) (

Table 3).

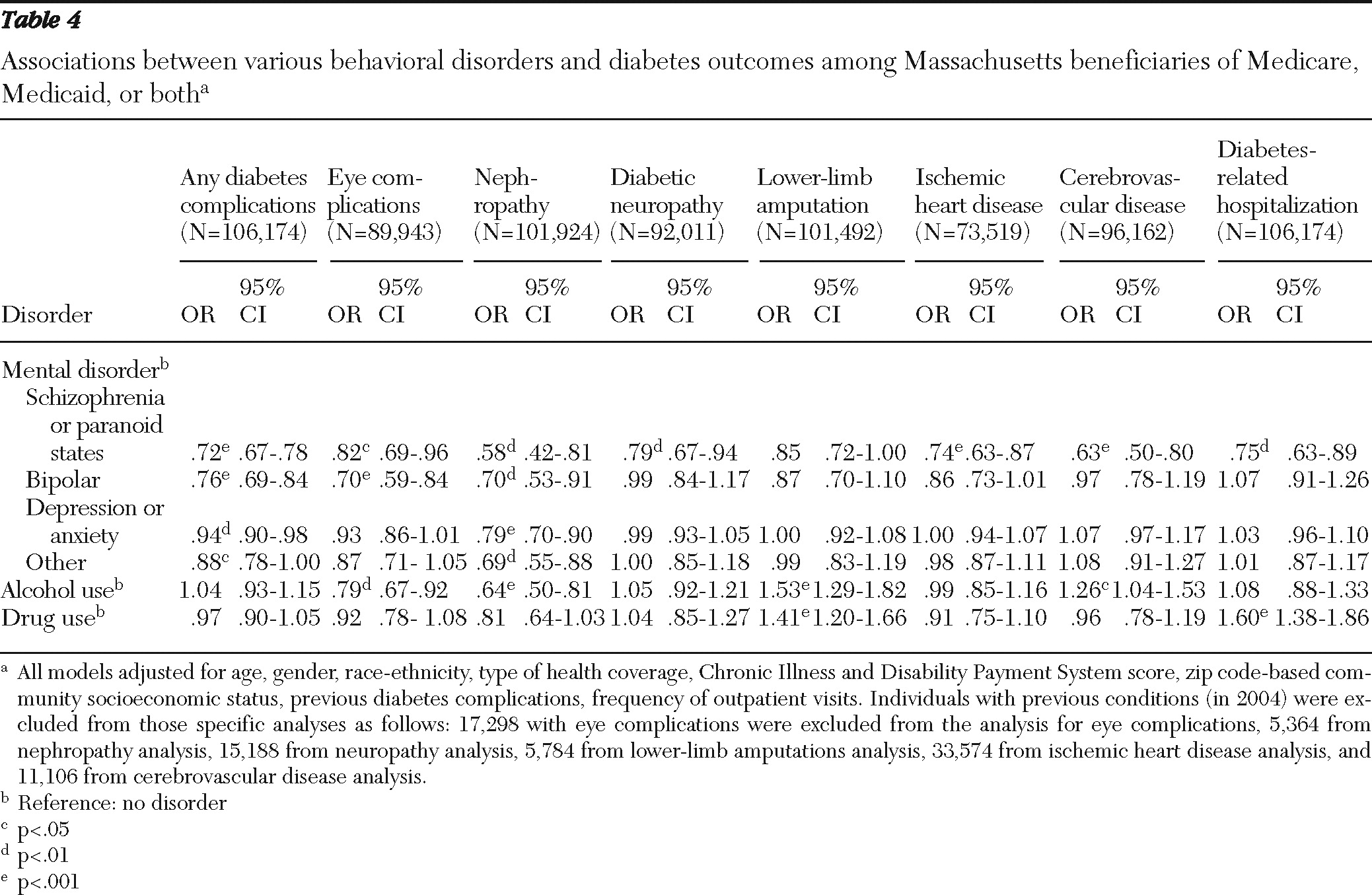

Compared with those with no mental disorders, beneficiaries with schizophrenia or paranoid states had lower likelihood of any new diabetes complications (OR=.72), nephropathy (OR=.58), diabetic neuropathy (OR=.79), ischemic heart disease (OR=.74), cerebrovascular disease (OR=.63), and diabetes-related hospitalizations (OR=.75) (

Table 4). Beneficiaries with bipolar disorder were less likely than those with no mental disorders to have new cases of any diabetes complications (OR=.76), eye complications (OR=.70), and nephropathy (OR=.70). Beneficiaries with depression or anxiety had lower odds of having new cases of any diabetes complications (OR=.94) or nephropathy (OR=.79) compared with those with no mental disorders. Similarly, beneficiaries with other mental disorders were less likely than those with no mental disorders to have new cases of nephropathy (OR=.69).

Beneficiaries with any alcohol use disorder had lower likelihood of eye complications (OR= .79) and nephropathy (OR=.64) than those with no alcohol use disorder (

Table 4). However, they were more likely to have lower-limb amputations (OR= 1.53). Compared with those with no drug use disorder, beneficiaries with a drug use disorder had higher odds of lower-limb amputations (OR= 1.41) and diabetes-related hospitalizations (OR=1.60).

There were other factors associated with the odds of having diabetes complications and hospitalizations. For example, male gender (OR=1.17, 95% confidence interval [CI]= .11–1.24) and having had previous eye complications (OR=1.24, CI=1.15–1.34) were correlated with increased odds of diabetes-related hospitalizations (data not shown). However, having continuous 12-month health coverage was associated with lower odds of diabetes-related hospitalizations (OR=.55, CI=.48–.62).

Discussion

In this study we observed that Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries with type 2 diabetes and co-occurring schizophrenia or paranoid states had lower odds of adverse diabetes outcomes but individuals with drug use disorders had higher odds of diabetes-related hospitalizations. Similar findings on substance use disorders and poor health outcomes in diabetes have been reported in previous studies of different patient groups (

3,

6). However, contrary to previous studies (

1–

3), our study results did not indicate that mental disorders were associated with higher likelihoods of adverse diabetes outcomes. For example, in a study using administrative data, Krein and colleagues (

2) observed that people with diabetes and schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were more likely to be hospitalized. However, they did not assess or adjust for substance use disorders in the analysis. Substance use disorders have high rates of co-occurrence with serious mental disorders in the general population (

7). Therefore, the effects of mental disorders on diabetes outcomes might be confounded by unmeasured substance use disorders. Further analysis of our study population revealed that substance use disorders co-occurred frequently with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in the study population, at 22% and 26%, respectively.

It is worth noting that the prevalence of any new diabetes complications in this population of beneficiaries was about 50% in 2005. In general, higher rates of diabetes complications were observed in the study population than in the overall U.S. population with diabetes. For example, the prevalence of ischemic heart disease in 2005 was 32.0% in this population, compared with the national figure of 22.3% in 2003 (

8). Similarly, the rate of hospitalization with diabetes as the first diagnosis was 56.9 per 1,000 persons in the study population, compared with 35.9 per 1,000 persons nationally in 2005 (

9). Thus there is reason to believe that beneficiaries of Medicare, Medicaid, or both had higher disease burden and worse health outcomes than the general population. Such observations may also reflect the lack of proper diabetes care among these beneficiaries. For example, in a separate analysis, our research team observed that compared with the general population, the study population had lower rates of receiving laboratory tests and clinical exams to monitor diabetes (

10). Therefore, more efforts should be made to improve the quality of diabetes care as well as health outcomes among these beneficiaries.

This study has several limitations. First, the duration of observation was short (that is, just one year). Diabetes complications are generally slow processes and take years to develop. Therefore, the study was unable to capture the natural history of diabetes complications and might have underestimated their incidence. Further studies with multiyear data are necessary to accurately estimate the occurrence of adverse diabetes outcomes. We also note that the outcomes captured by claims data in this study only represent “diagnosed” prevalence of diabetes complications, not the “true” rates of adverse outcomes in the population. For the outcomes to be recorded in claims, the beneficiaries must first have sought care in clinical settings. Rates of the disease diagnoses and treatment thus depended on the likelihoods of the beneficiaries' care seeking.

Second, it is likely that the study underestimated the prevalence of behavioral disorders because of reliance on claims data. Disorders noted in claims data have been diagnosed and recorded; therefore, it is possible that those classified as “no behavioral disorders” might actually have had behavioral disorders. Previously published studies showed that behavioral disorders can be undiagnosed by clinicians (

11) or recorded inaccurately in the database (

12,

13). For example, Kessler and colleagues (

11) observed that patients who tended to consider their psychiatric symptoms as manifestations of somatic diseases were less likely to be diagnosed in primary care settings as having mental disorders.

Our analysis covered Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries in one state. Variation in the quality of care across geographic regions is well documented, and it is likely that similar studies in other states may yield different results. Health care resources available to Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries are greater in Massachusetts than in many other states.

Although it was not the focus of this analysis, the finding that continuous coverage was associated with less frequent diabetes-related hospitalization suggests the importance of sustained access to care. Medicaid enrollment policies and procedures often lead to periods of disenrollment during which individuals are without health coverage. Individuals with addiction may be particularly vulnerable to such breaks in coverage. In our sample, substance use disorders were associated with lower rates of continuous 12-month coverage within each of the mental illness groups. Thus, in addition to factors discussed above, it is likely that substance abuse or dependence increases health care costs by leading to breaks in coverage.

Conclusions

Our analysis revealed a mixed picture of diabetes complications among individuals with co-occurring behavioral disorders. Individuals with diagnoses of mental disorders tended to have fewer complications, but the strength of the association (odds ratio) varied by diagnostic group. However, those with alcohol or drug use disorders were at significant risk of the most severe complications, such as lower-limb amputations and cerebrovascular disease. Drug use disorders were also associated with more frequent hospitalization to treat diabetes. The reasons for these associations are not clear, but they go beyond simple access to medical care or frequency of use; we controlled for continuous coverage and for the number of medical visits in our model.

There is some evidence that the quality of care for patients with addictions is lower (

14–

17). Other studies show that physicians often describe visits with patients having an addiction as difficult (

18,

19). And difficult visits are likely to result in unmet needs (

20). Poorer self-care among patients with addiction may also play a role (

21). Although all of these potential explanations need further exploration, it is clear that an increased emphasis on identifying diabetes patients with co-occurring substance use disorders should be a priority of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and of Medicare and Medicaid providers. Targeted interventions for patients may be necessary, but such interventions should also be coupled with training and assistance for providers in managing difficult encounters. It is unlikely that a single solution will address the complex problem of helping individuals with addiction manage their diabetes and avoid stroke, foot or leg amputation, and other complications.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The first author thanks Becky A. Briesacher, Ph.D., for her advice concerning the statistical analyses.

The authors report no competing interests.