Recruitment

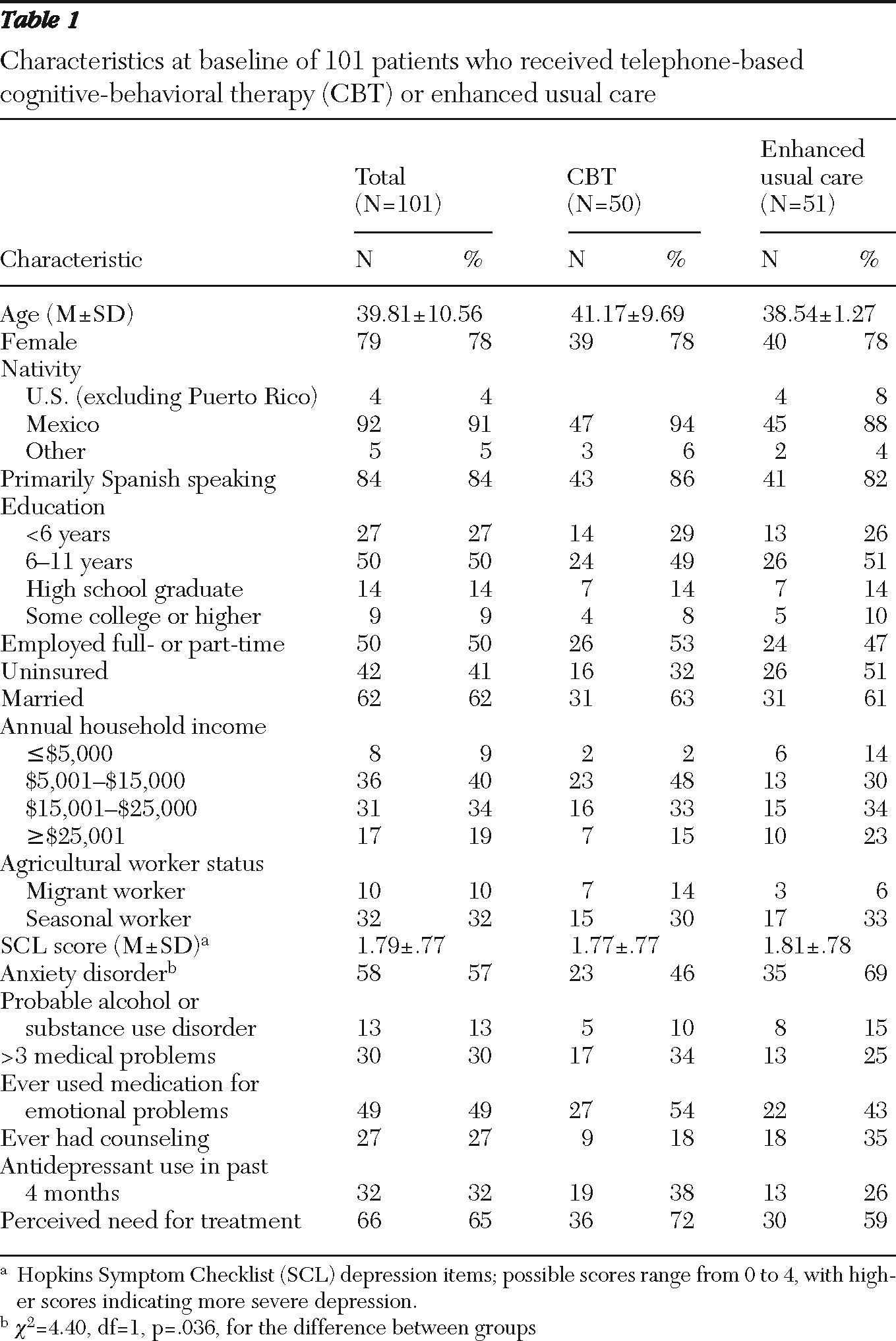

Three local residents who spoke both Spanish and English and who were familiar with both the local Mexican-American and mainstream cultures were trained and hired part-time to approach patients in the waiting room to ask if they would like to hear about a depression research study. Clinic providers could also refer patients for screening. Patients who agreed were taken to a private area where study recruiters conducted a brief interview. Adult primary care patients were eligible for the study if they self-identified as Latino; spoke English or Spanish; screened positive for probable major depressive disorder; and screened negative for bipolar disorder, cognitive impairment, current or lifetime psychotic symptoms or disorder, current substance abuse, or acute suicidal ideation. Patients were eligible even if they were already receiving antidepressant medication. No study-eligible patient had to be excluded because of lack of access to a telephone.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used to assess probable major depression; criteria were the reporting of a minimum of five of the nine symptoms assessed and a cutoff score of 10 (

13,

14). Probable bipolar disorder was assessed using the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (

15). We screened for psychotic disorders using three stem items from the psychotic disorders module of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (

16) and one question regarding lifetime history of psychotic disorder from the Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) study (

17). Cognitive impairment was assessed by using a six-item screener derived from the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (

18). The MMSE is validated in Spanish and among Mexican Americans (

19), and we employed the six-item screener in previous trials with low-income Latino patients in primary care (

20). Suicidal ideation was assessed by using a protocol based on the PHQ-9 and standard clinical interviews. The CAGE-AID, a four-item questionnaire validated among primary care patients, was used to screen out current alcohol and substance abuse (

21). Using the validated Spanish version of the CAGE, known as the 4M (

22), as a guide, the CAGE-AID was translated into Spanish, reviewed, and translated back into English by bilingual study personnel from at least two Spanish-speaking countries.

Patients who responded affirmatively when asked if during the past two weeks they had had thoughts that they would be better off dead or had wanted to hurt themselves were asked structured questions devised by the study team to assess suicidal ideation. The recruiters also used a standardized procedure to discuss the case with the principal investigators, arrange urgent evaluation if necessary, and communicate the safety plan to the primary care provider.

Study procedures were explained fully to the patients, and written informed consent in the patient's preferred language was obtained. Enrolled patients completed baseline surveys described below. Patients were then assigned to receive usual care or CBT by telephone by stratified permuted-block randomization, with strata defined by gender and referral source.

CBT by telephone

CBT was provided at no charge in eight telephone sessions; each session focused on a chapter from a patient workbook that had been translated into the Spanish language for this study (

9). The content of examples and vignettes were modified to use Latino names and reflect situations relevant to rural Latinos. Bilingual members of the study team (some with farm worker backgrounds) reviewed the translated manual to ensure that language, idioms, and vignettes were appropriate for the local Latino context and culture. The workbook included didactic material, exercises for each session, and written exercises for completion between sessions. The workbook was mailed to participants in the CBT telephone intervention after randomization, and patients were asked to read the relevant workbook chapter before each session.

In general, patients completed the modules in order, but the schedule was sometimes modified—for example, to switch the order of modules or to use two sessions for a single module. In response to the cultural value of personalismo, patients were given the option to conduct their first session in person. Each session was scheduled in advance (approximately weekly), but missed appointments were frequent, necessitating that therapists extend persistent outreach and expand traditional clinic hours to accommodate patients' work schedules. Sessions were designed to last 45 to 50 minutes, but the actual duration varied according to clinical need and patient preference.

The content of the phone interventions is described elsewhere (

10); briefly, each intervention emphasized behavioral activation (

23,

24) and strategies for identifying, interrupting, and distancing oneself from negative thoughts (

25,

26). During each session, therapists followed a detailed outline. Each session included structured assessment of depressive symptoms with the PHQ-9 (

27) (five minutes), review of the previous session's content (five minutes); debriefing of previous homework assignment (five to ten minutes), introduction of new material (15 to 20 minutes), description of the new homework assignment (five to ten minutes), and a motivational assessment and enhancement exercise focused on the homework assignment (five minutes).

The initial session also included a structured assessment of clinical history, assessment of motivation for treatment, and use of strategies to enhance patients' motivation to engage in treatment, such as exploring options for depression treatment and feelings of ambivalence about treatment (

28). If indicated by symptom acuity, therapists made brief supportive telephone contacts between sessions.

Based on clinical judgment, the study therapist could refer the patient for case management services for depression care needs, such as assistance in making appointments with clinic providers and referrals to community services. The therapist did not take an active role in management of antidepressant medication but could discuss medication as a treatment option, ask about medication adherence, and—with participants' consent—communicate with prescribing providers. The therapist made no specific medication recommendations, and all questions related to medication were referred back to prescribing physicians.

Telephone sessions were conducted by five part-time therapists hired for the study: a student working toward a master of social work degree (M.S.W.) who had experience as a community social worker, an experienced therapist with an M.S.W., an individual with an M.S.W. and experience in social work but not in therapy, and two M.S.W. students with limited clinical experience. All were Latino or Latina and spoke Spanish.

The therapists' training for the study consisted of a full-day workshop introducing general concepts of the intervention and reviewing the eight sessions. Next, each therapist reviewed the manual independently and then participated in a group teleconference to review questions and role-play material from the first session. The two M.S.W.-student therapists augmented this training by role-playing the entire manual by telephone.

Each study therapist was assigned up to two practice cases. As each session was completed, the therapist sent encrypted digital recordings to an interdisciplinary group of supervisors (two social workers, a psychiatrist, and a psychologist), who provided feedback in weekly group telephone supervision. Once each therapist was deemed competent by the supervision team, he or she was assigned study cases. The therapists continued to have weekly group supervision, and selected session recordings were reviewed by supervisors throughout the study.

Each therapist was asked to complete a computerized tracking sheet that recorded each patient contact (including no-shows and reminder calls) and patients' depressive symptom severity as measured by the PHQ-9 (

27) at each session. Supervisors and therapists used these sheets to review the status of their caseload during weekly supervision.

Analyses

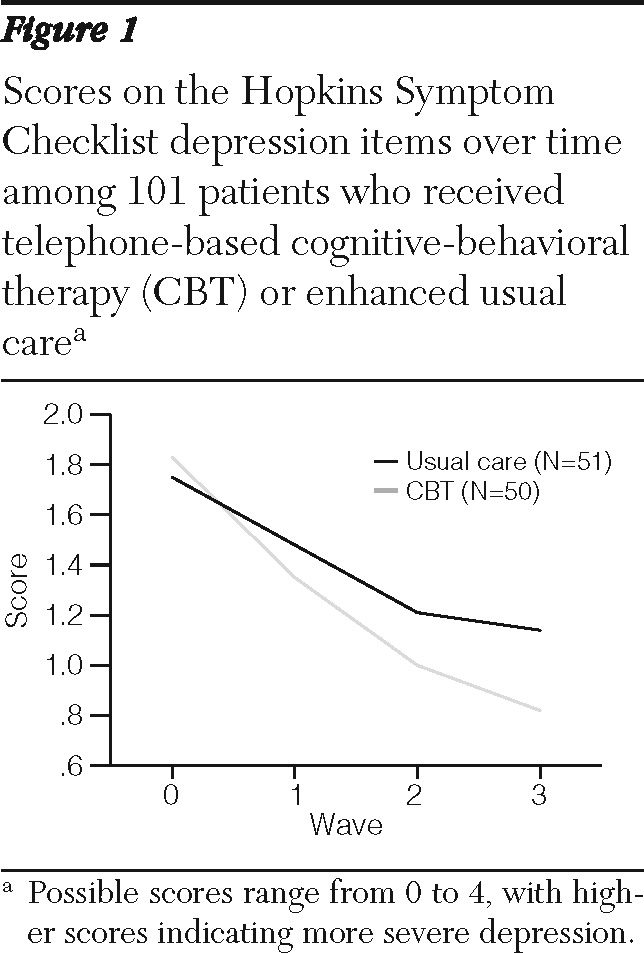

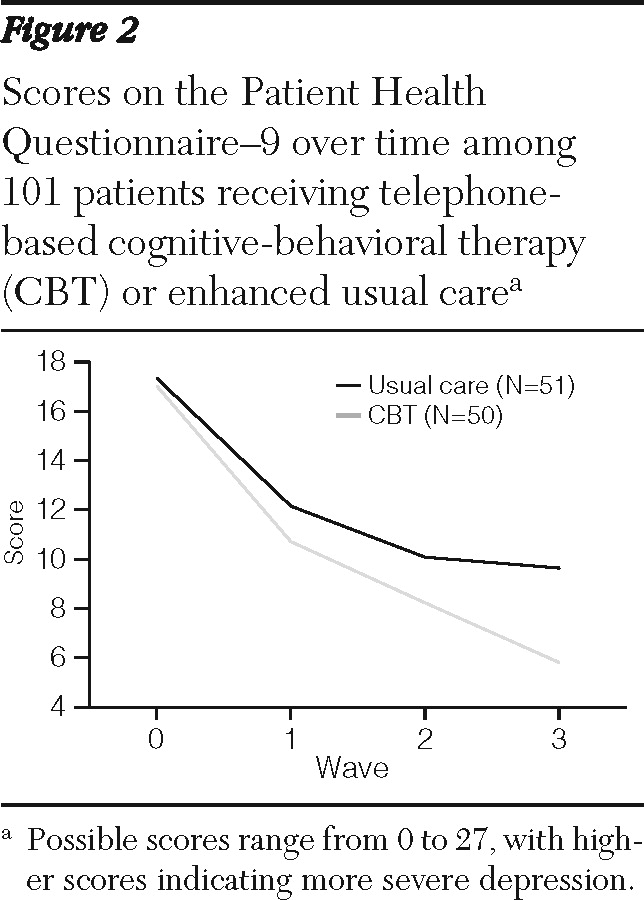

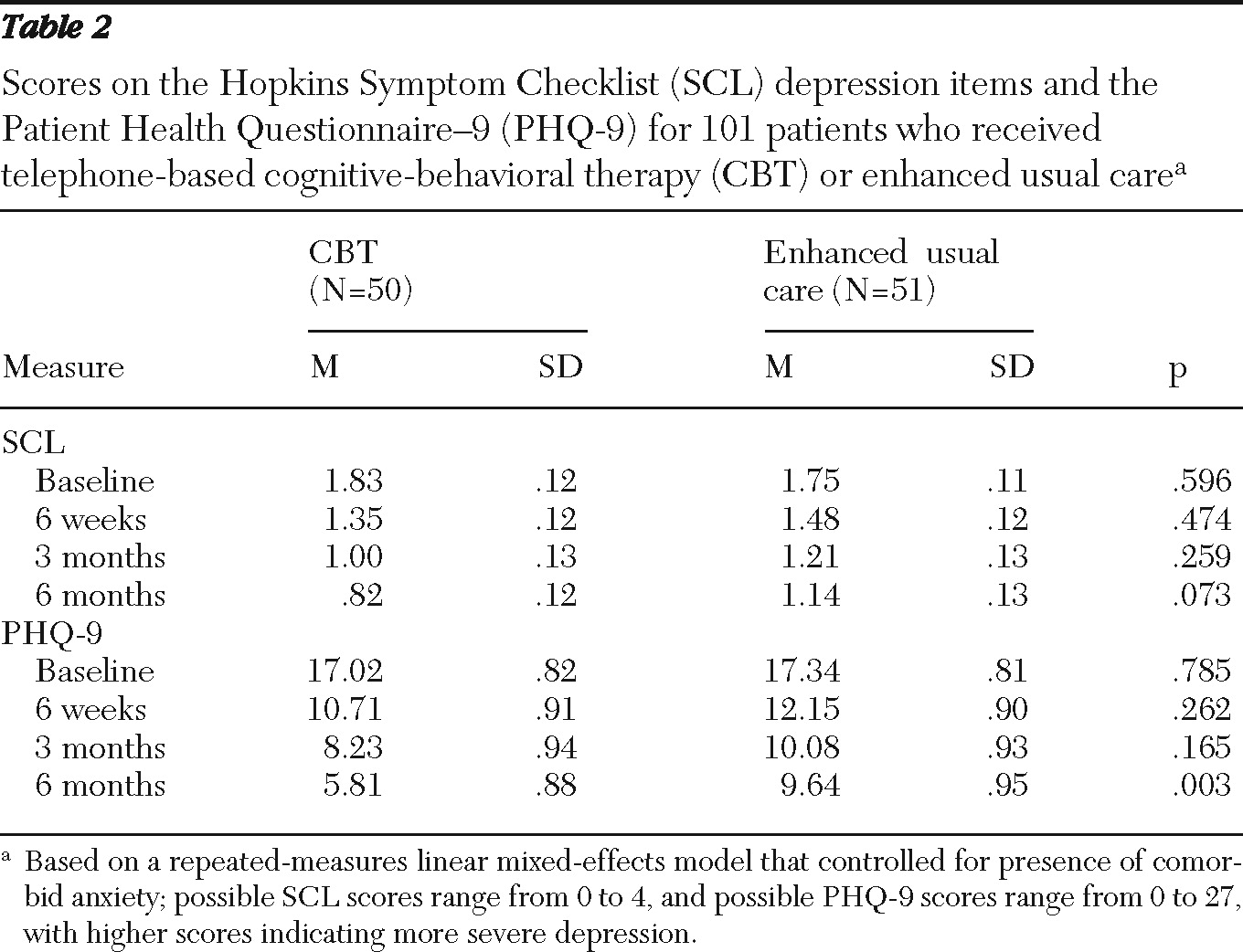

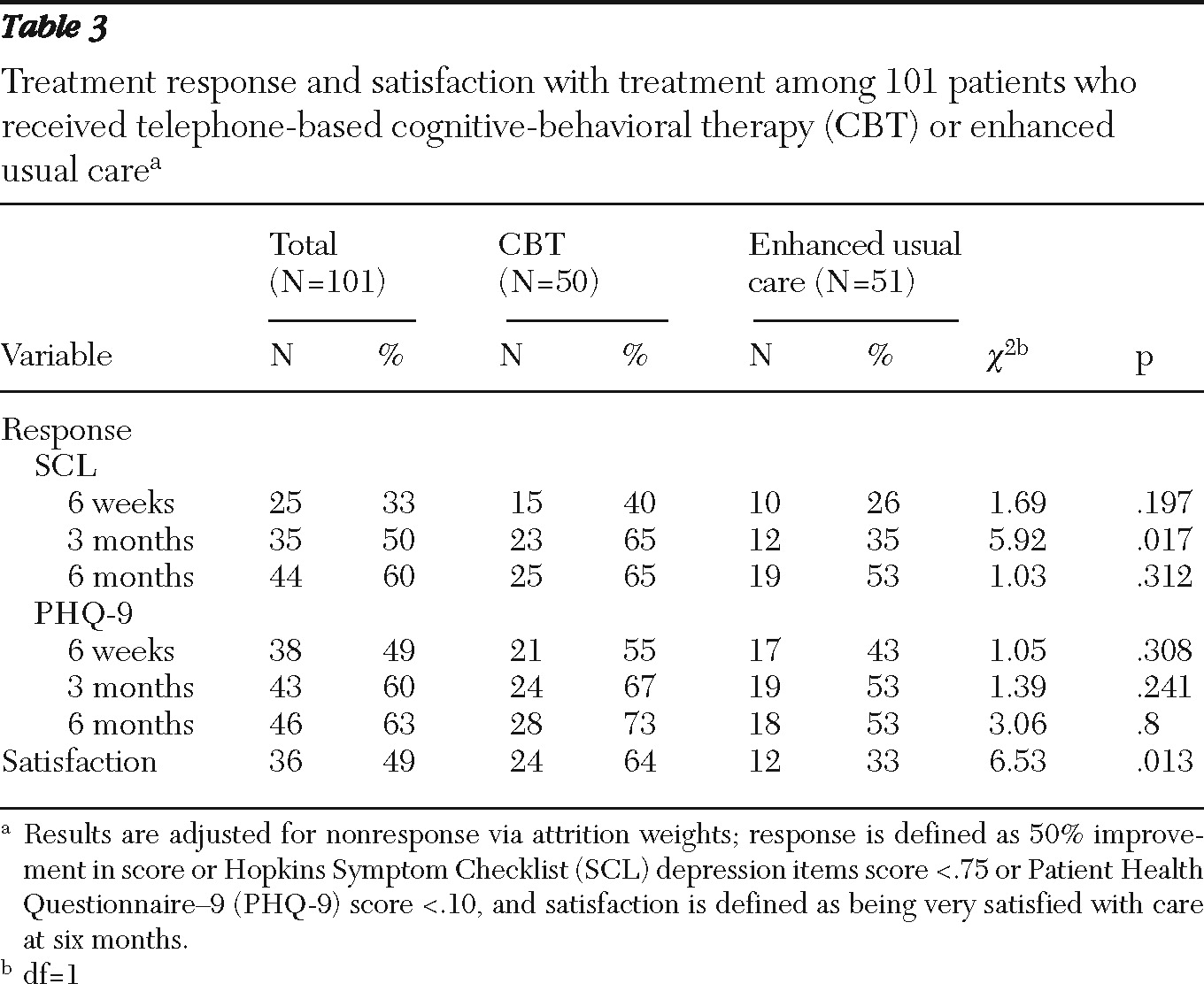

Using t tests and chi square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively, we compared demographic characteristics and depression symptoms at baseline by intervention group. To determine the intervention effect, we used an intent-to-treat approach, in which all eligible patients with a baseline interview were included in analyses even if they missed interviews or did not participate in treatment sessions. To estimate the intervention effect over time, we jointly modeled the outcomes at the four assessment times (baseline, six weeks, three months, and six months) by time, intervention, and the interaction between time and intervention using a mixed-effects model (in which patients' data were treated as random effects). The beta coefficient associated with each assessment time represents the average change from baseline experienced by the CBT group above and beyond that experienced by the group receiving enhanced usual care. Time was treated as a categorical variable, and all the models included probable anxiety disorder as a covariate because patients receiving enhanced usual care were significantly more likely to screen positive for anxiety disorders at baseline.

There was a trend toward lower rates of insurance coverage among patients who received enhanced usual care compared with those receiving CBT; however, baseline insurance status was not predictive of outcomes, and inclusion of insurance status as a covariate in the models did not significantly change results. Thus insurance status was dropped from the final models. We fitted the model using a restricted maximum-likelihood approach, which produces valid estimates under the missing-at-random assumption (

37). This approach correctly handles the additional uncertainty arising from missing data and uses all available data to obtain unbiased estimates for model parameters (

38). For cross-sectional analyses, such as those assessing the percentage of responders at the three follow-up times, we used attrition weights to correctly account for patients who missed one or more follow-up assessments (

39). For all analyses we used R, version 2.11.1.