Bipolar disorder is a major public health issue in the United States. It is estimated that bipolar disorder affects 5.7 million Americans, or 2.6% of the adult population, annually, with an average lifetime cost per case in 1998 of $252,212 (range=$11,720 to $634,785), including direct and indirect costs (

1,

2). In a cross-sectional survey, 249 participants with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder were compared with age- and gender-matched normative subjects (

3). Persons with bipolar disorder were more likely to miss work, to have a reduced work schedule for medical reasons, and to have higher utilization of health care resources, including emergency department visits.

The cost of bipolar disorder for U.S. workplace productivity has been estimated to be more than $14.1 billion annually, with more than 65 days of work lost yearly per worker in the affected population (

4). In addition to the cost of workplace productivity losses, partial adherence and nonadherence to medications have been found to be associated with an increased risk of mood episode relapse, suicide attempts, and hospitalization, resulting in an increased cost to society (

5). In a 2005 study assessing adherence to treatment and resource utilization in a Medicaid population with mental illness, partial adherence was associated with a 49% greater likelihood of inpatient hospitalization and a 54% greater cost for the inpatient stay, as well as a higher rate of changes in drug therapy among patients being treated with second-generation antipsychotic medications (

6).

The use of second-generation antipsychotics in bipolar disorder has risen dramatically in the past decade, with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's approval of several of these medications for both acute and maintenance treatment indications. Sankaranarayanan and Puumala (

7) found that adult ambulatory care visits where second-generation antipsychotics were prescribed were significantly more common for patients who had nonpsychotic mental illnesses, including bipolar disorder. From 1996 to 2003, the number of prescriptions for second-generation antipsychotics during ambulatory care visits increased by 195% (

6). The increased use of these medications has led to a greater cost burden for state Medicaid programs, with Medicaid expenditures for antipsychotic medications overall increasing 154% from 1997 to 2002 (

8).

The purpose of this retrospective analysis of Medicaid claims data was to identify patients with bipolar disorder for whom clinically recommended doses of oral second-generation antipsychotics (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone) were prescribed and to evaluate adherence and persistence of use across medication groups. In addition, mental health-related medical care costs and total medical care costs were evaluated.

The primary objective of this study was to assess suboptimal use of oral second-generation antipsychotic medications (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) in comparison with ziprasidone in a multistate Medicaid population. For the subset of patients for whom clinically recommended doses of second-generation antipsychotics were prescribed, comparisons were conducted for medication adherence, persistence of medication use, mental health-related costs, and total medical costs.

Methods

Data source

This study was a retrospective analysis of claims data for Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder diagnoses from eight states. Eligibility data and paid medical and pharmacy claims were extracted from the Texas Medicaid Vendor Drug and the Texas Medicaid Medical Services claims databases, as well as from the Thomson Reuters MarketScan research database, which provided medical and pharmacy paid claims and eligibility data from seven Medicaid agencies representing geographically diverse states. All medical files contained claims from inpatient and outpatient services. Diagnoses were provided in the

ICD-9-CM format (

10). Medical service claims included a primary diagnosis, service date, and payment amount. Prescription claim files included a National Drug Code, service date, quantity, days' supply, and payment amount. Eligibility files contained data on age, gender, and race-ethnicity and a monthly history of Medicaid eligibility. All data were deidentified, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas at Austin.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Claims data from 2002 through 2008 were obtained. The index prescription date was defined as the date of the first claim for one of the following oral second-generation antipsychotics: aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. The study period for each patient was 18 months and included the six months before and the 12 months after the index second-generation antipsychotic prescription. Patients were naïve to any second-generation antipsychotic for at least six months before their index prescription date but could be taking other medications for treatment of bipolar disorder.

Included in the study were patients who had an initial prescription for one of the five second-generation antipsychotics between July 1, 2002, and December 31, 2007; had a principal diagnosis of bipolar disorder (ICD-9-CM codes 296.0X, 296.1X, 296.4X, 296.6X, or 296.81) during the study period; were continuously enrolled in Medicaid six months before and 12 months after the index prescription date; and were between age 18 and 64 years at the index prescription date.

Patients were excluded if they had a principal diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 295.XX) during the study period, a claim for clozapine during the study period, a diagnosis of epilepsy (ICD-9-CM 345.1, 345.4, and 345.5) during the six months before the index prescription date, a claim for a second-generation antipsychotic during the six months before the index prescription date, or claims for more than one second-generation antipsychotic on the index prescription date.

Patients were assigned to one of five cohorts on the basis of their first second-generation antipsychotic medication during the index period. These groups were further classified according to whether a clinically recommended dose was prescribed, on the basis of the daily dose 60 days after the index prescription date. This time period was chosen to allow adequate time for dose titration. Clinically recommended dose ranges for bipolar disorder, derived from product package inserts and published literature, were 10–30 mg per day for aripiprazole (

11–

14), 10–20 mg per day for olanzapine (

14–

17), 300–800 mg per day for quetiapine (

14,

18–

20), 2–8 mg per day for risperidone (

14,

21–

23), and 80–160 mg per day for ziprasidone (

14,

24–

26).

Study measures

The study measures consisted of medication adherence, persistence of medication use, and costs. Medication adherence is the “extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose of a dosing regimen” (

27,

28). In this study, adherence was operationalized by using the medication possession ratio (MPR). The MPR numerator was the sum of the days' supply for all index medication fills during the study period. The denominator was the number of days between index and end date of the last index medication dispensed during the study period. MPRs greater than 1.0 were truncated at 1.0. Patients were considered to be adherent if the MPR was ≥.8 and were considered to be nonadherent if the MPR was <.8.

Persistence of medication use is the duration of therapy from initiation of the index medication until discontinuation (

27,

28). Discontinuation was defined as a gap of greater than 30 days between index medication fills. Persistence of use was calculated by summing the number of days from the index prescription to the end date of the last index medication claim before a gap of greater than 30 days.

Costs were defined as the amount reimbursed by Medicaid for medical and prescription claims during the study period. Four types of summary costs were calculated: mental health-related prescription costs, total mental health-related costs (prescription and medical claims), total prescription costs, and total costs (total prescription and medical claims).

Data analyses

Data for patients for whom clinically recommended doses of second-generation antipsychotics were prescribed were included in the analyses. Comparisons were used to examine differences between patients in the ziprasidone cohort (comparator category) and patients in the aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone cohorts.

The likelihood of adherence (MPR ≥.8) was estimated with logistic regression analyses. Baseline covariates included age, gender, race-ethnicity, Charlson comorbidity score (

29), specific comorbidities, and concomitant use of other medications for bipolar disorder. The Charlson Comorbidity Index uses a range of comorbid conditions, such as heart disease, AIDS, or cancer (a total of 22 conditions). Each condition is assigned a score of 1, 2, 3, or 6, depending on the risk of dying associated with this condition. Then the scores are summed up to a total score that predicts mortality (

29). Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

The risk (hazard) of discontinuing medication use (that is, becoming nonpersistent) was compared by using Cox's proportional hazard models. Baseline covariates included age, gender, race-ethnicity, Charlson Comorbidity Index score (

29), specific comorbidities, and concomitant use of other medications for bipolar disorder. Hazard ratios and 95% CIs were calculated.

Generalized linear models with a gamma distribution and log-link were used to estimate postindex annual costs. Baseline covariates included age, gender, race-ethnicity, Charlson Comorbidity Index score (

29), specific comorbidities, and concomitant use of other medications for bipolar disorder. To calculate mental health-related costs, the log of preindex mental health-related costs was used as a covariate. When comparing all costs, the log of preindex costs for all diagnoses was used as a covariate.

Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS, and alpha was set at .05.

Discussion

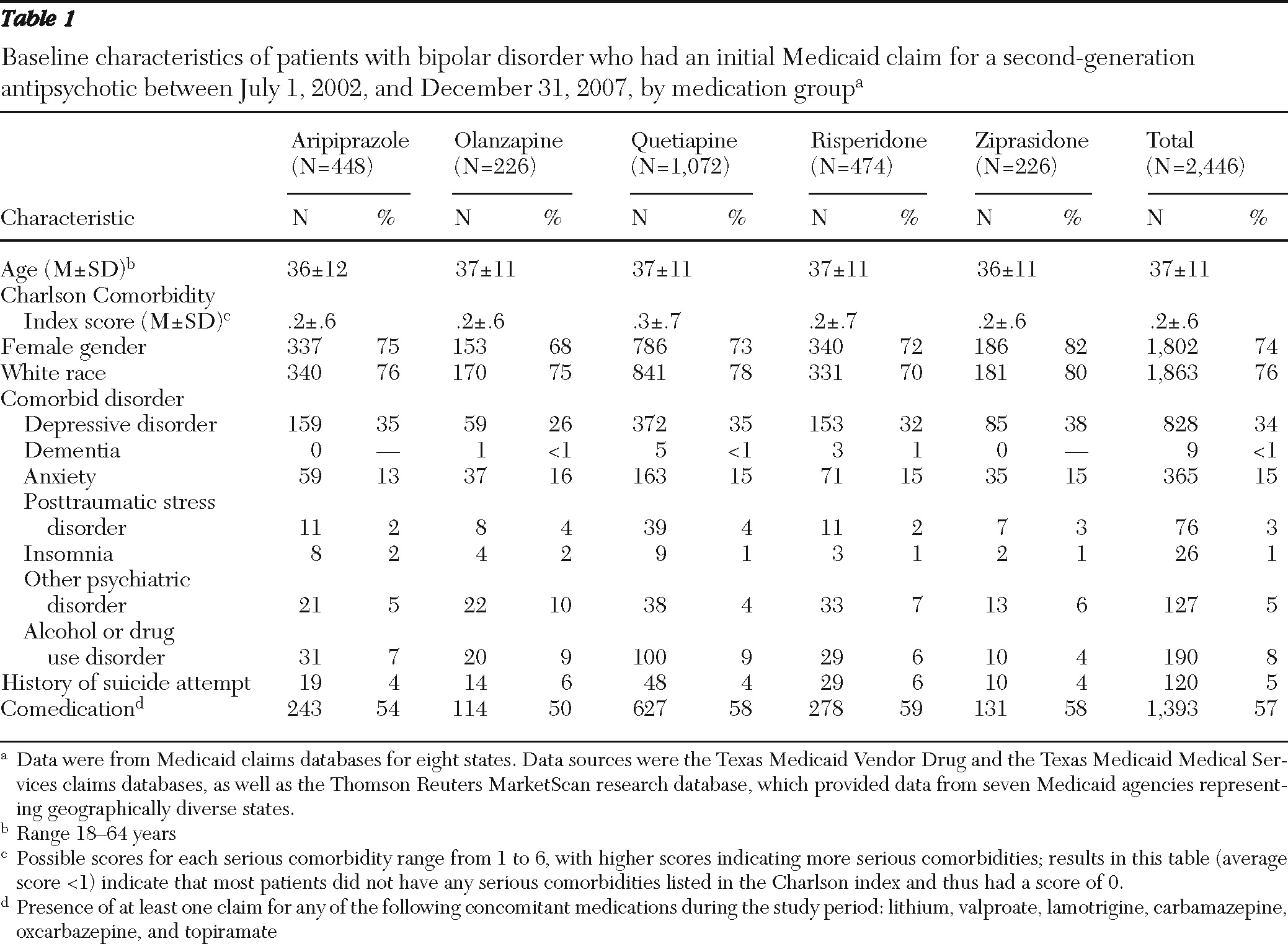

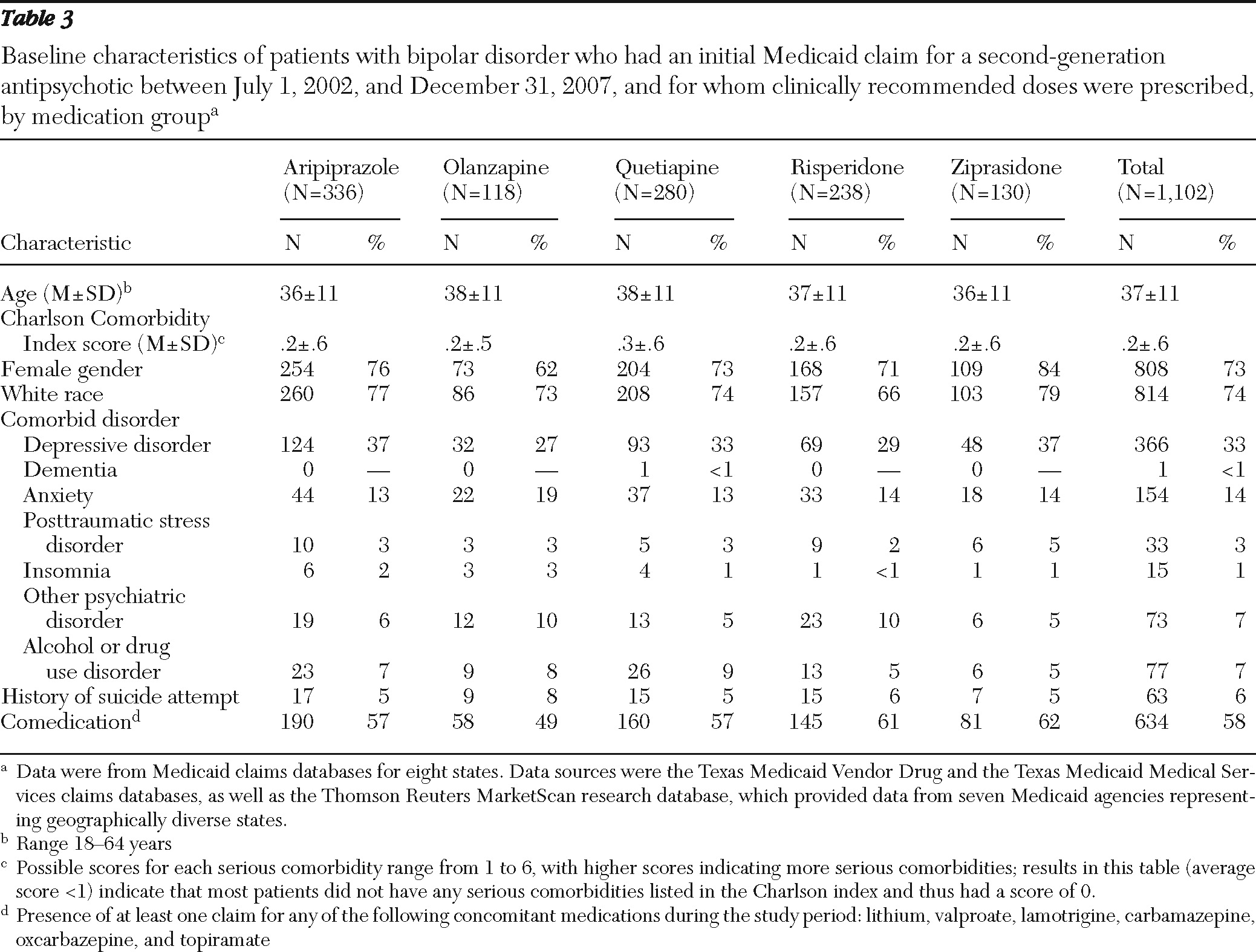

Strengths of this Medicaid database study include the moderately large group of patients with bipolar disorder (N=2,446) whose data were included, careful selection criteria, analysis of data for patients for whom clinically recommended doses of second-generation antipsychotics were prescribed, and a clinically meaningful study follow-up period of 12 months. Although the results of this analysis are specific to the study group, the geographic diversity of the sample, which comprised Medicaid recipients in eight states, increases the potential for this analysis to inform other Medicaid plans. Other strengths include the demographic and clinical similarity of the patients in the medication groups that were compared and the application of modern regression techniques to provide an efficient yet comprehensive analysis of the sizeable data set. Data from 2002 to 2008 were used in the analyses, and although changes in usage patterns may have occurred during this time, no temporal trends were seen for adherence and persistence.

Limitations of the work include the retrospective nature of the data. In addition, although the analysis may have substantial implications for Medicaid patients, the results may have limited applicability to non-Medicaid patients because of a variety of demographic and health system factors. Also, studies based on administrative claims data have inherent limitations, such as selection bias, as well as limited direct information about clinical status and functioning. It is difficult to fully control for potential confounders such as disease severity because complete measures of severity are not routinely collected in claims databases. Therefore, surrogate markers of severity, including baseline comorbidities and preindex costs, were utilized in these analyses. In addition, patients 64 years and older were not included in the analyses because of a lack of complete medical utilization data as a result of dual Medicare-Medicaid eligibility status.

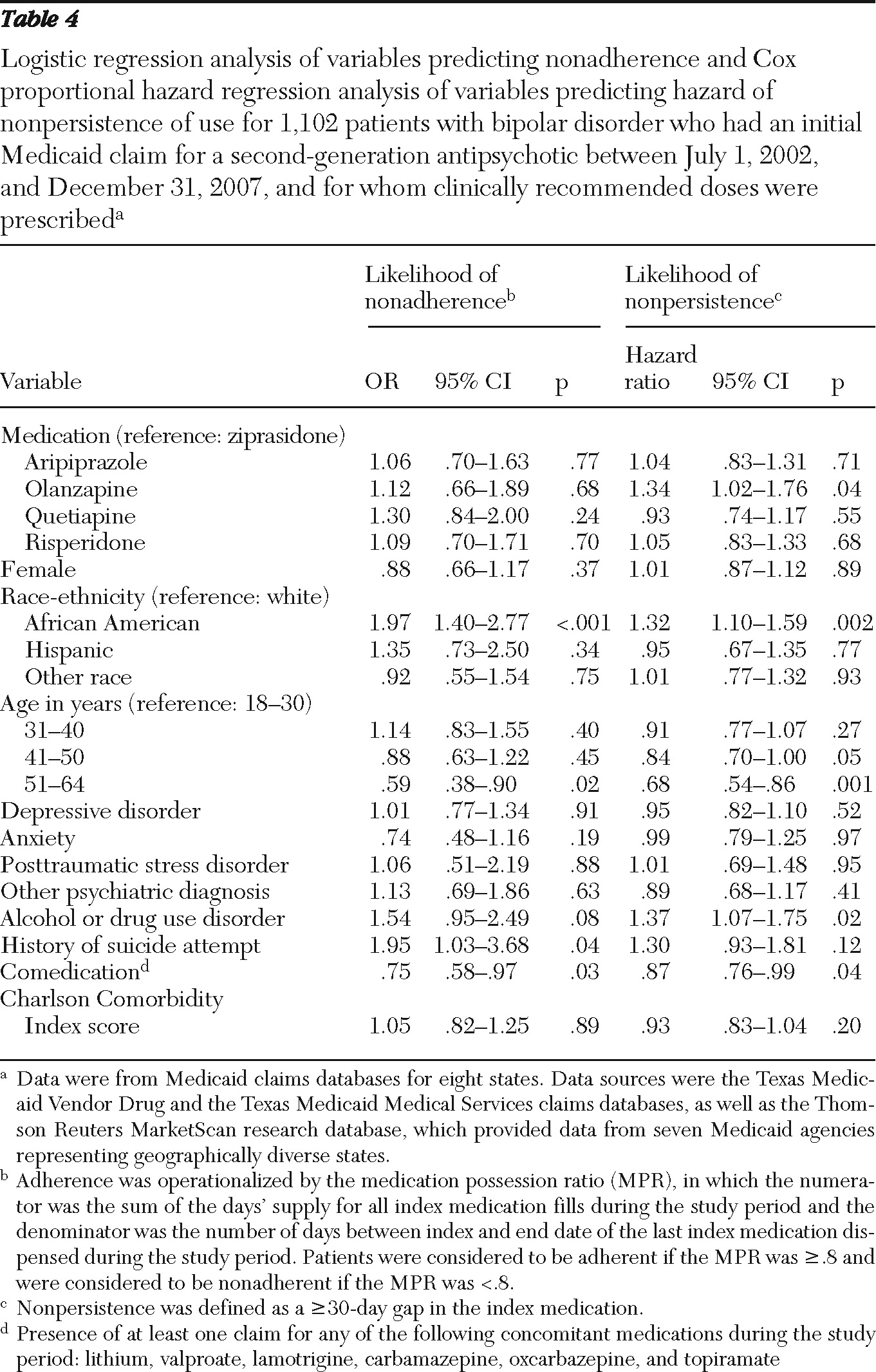

A number of key observations resulted from the study. As in previous studies of bipolar disorder, which showed low rates of medication adherence (41% in the study by Lage and Hassan [

30] and 52% in the study by Sajatovic and colleagues [

31]), we found a low adherence rate of 58% for the index therapy among patients with bipolar disorder for whom second-generation antipsychotics were prescribed. Persistence of use for second-generation antipsychotic therapy averaged about three months in our study, and only 18% of patients continued to take the index second-generation antipsychotic 12 months beyond the index date. Furthermore, less than 50% of the cohort had clinically recommended second-generation antipsychotic doses after two months of treatment, conveying an overall picture of undertreatment with second-generation antipsychotics.

We identified a few major differences in key outcome measures among medication groups. One was that quetiapine, which was the most frequently prescribed second-generation antipsychotic in the study, was also associated with the lowest proportion of patients with clinically recommended doses at the end of acute treatment (two months). Owing to its sedative properties, quetiapine is often used as an adjunctive therapy to other non-second-generation antipsychotic mood stabilizers for treatment of clinical features associated with bipolar disorder, such as anxiety, insomnia, and persistent dysphoria. These additional indications usually require lower doses (less than 200 mg per day), and these reasons were not specifically flagged in the database unless an additional anxiety or sleep disorder was coded. One hypothesis for the failure to reach clinically recommended dosing with quetiapine in the initial months of therapy is the somewhat more onerous upward titration schedule for quetiapine, compared with other second-generation antipsychotics (

32).

Second, we observed, somewhat unexpectedly, that olanzapine treatment was associated with an earlier time to nonpersistence (72 days, compared with the median of 96 days for all medications). This finding is counter to findings of similar effectiveness trials in other populations with severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, in which olanzapine was associated with the longest time to discontinuation compared with other second-generation antipsychotics (

33,

34). However, findings from exploratory studies suggest that patients with bipolar disorder may be more sensitive to the neurocognitive side effects of the second-generation antipsychotics with sedative properties, which may adversely affect cognition (especially attention), resulting in reduced rates of longer-term adherence with therapy among patients with this disorder (

35). Using treatment episodes to assess treatment duration per bipolar episode, Gianfrancesco and colleagues (

36) found that the durations of treatment with quetiapine and with risperidone were longer than those for olanzapine and ziprasidone.

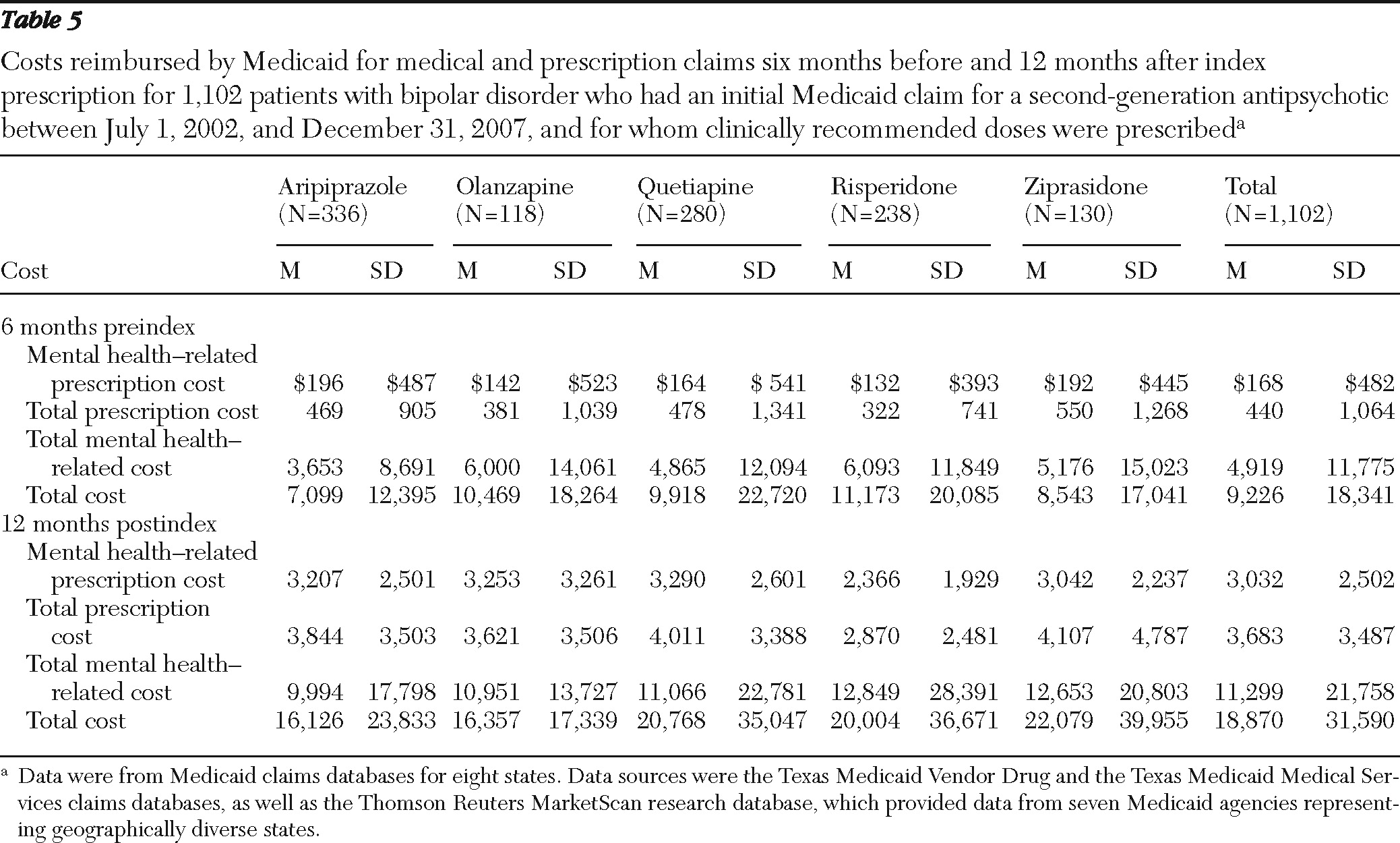

Third, prescription costs were lowest in the risperidone group. This finding is consistent with the availability of a generic compound during the study period. Otherwise, as found in previous studies (

37,

38), overall medical and mental health costs were similar across second-generation antipsychotic groups. Finally, several demographic findings should be noted in the overall data set. More than 70% of the study cohort was female, despite the gender equivalence of rates of bipolar disorder in the general community (

39). This finding could reflect the high proportion of TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program) single-parent families in the Medicaid program generally. Also, the risk of nonadherence (p<.001) and nonpersistence of use (p<.001) with second-generation antipsychotic therapy was higher among African-American patients than among white patients, as noted in previous studies (

40,

41). Future interventions related to care programming and policy for this population should take into account these demographic differences (

42). For this study, which looked at 12-month outcomes and costs, overall health costs were similar between African Americans and whites. Yet, over the long term, costs could be higher in this subgroup of Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder, because of the increased potential for relapse and need for future inpatient services.

The findings have several clinical and policy implications. The proper administration of second-generation antipsychotics in the stabilization and maintenance phases of bipolar disorder treatment is not trivial, considering the potential cost implications (

8). For example, a study of commercial pharmacy claims for patients with bipolar disorder (N=7,769) identified a clear inverse relationship between antipsychotic adherence level and frequency of emergency department and inpatient service utilization (

30). In addition, failure to achieve early and adequate stabilization treatment among younger patients with bipolar disorder may reduce potential neuroprotective effects of this medication class, with attendant long-term, negative prognostic implications (

43). Moreover, the kindling hypothesis of bipolar disorder (

44) would predict that clinically inadequate dosing of mood stabilizers could have a permissive effect on the occurrence of future mood episodes. The findings from this study underscore the need to use psychosocial interventions to augment the delivery of second-generation antipsychotic pharmacotherapies for Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder.

Patient-level interventions to promote clinically effective dosing, adherence, and persistence include care management, case management, and collaborative care approaches. However, relatively few data on these strategies exist that specifically inform the care of patients with bipolar disorder. In one randomized study of patients with chronic illness, simple reminder strategies (for example, phone reminders from the pharmacy to the patient or to the prescriber) did not significantly enhance persistence compared with usual care (

45). Employing a disease management model for Medicaid enrollees with serious and persistent mental illness (N=210), one pilot study of a telephone counseling intervention provided by a registered nurse and incorporating cognitive-behavioral and motivational enhancement techniques found increased second-generation antipsychotic adherence and reduced emergency department visits (

46). Educational strategies for improvement of adherence and persistence of use may also be fruitful areas for future testing and study. Patient-oriented psychoeducation interventions aimed at clarifying treatment expectations and the rationale for using the selected second-generation antipsychotic agent may promote treatment satisfaction, thereby affecting adherence and persistence of use. Additional clinician-oriented education programs explicating the various subtypes of adherence difficulties (voluntary, involuntary, irregular, and selective) are also likely to promote more effective responses to adherence problems in the second-generation antipsychotic therapy of bipolar disorder (

5).