The reliability of psychiatric diagnosis has been markedly enhanced through the use of standardized interview schedules (e.g., the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia [1], the Diagnostic Interview Schedule [2], and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R [3]). Although these interviews were developed for use in a face-to-face format, interviews that assess axis I and II disorders in research settings are often done by telephone (J. Endicott, D. Kilpatrick, and R. Kessler, personal communications, 1996). The major advantage of telephone interviews over face-to-face interviews is cost efficiency (

4). Telephone interviewing is also logistically simpler, especially if the participant resides in a geographically distant location. The extensive use of telephone interviews in research presupposes that the obtained diagnostic information is as valid as that obtained in person. The goal of the present study is to examine this assumption with regard to axis I and II diagnoses obtained in a group of young adults from the community.

In addition to the obvious research implications, understanding the adequacy of data obtained by telephone has clinical importance. Telephone-based programs have been used to screen for psychiatric difficulties such as depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder (

5,

6), administer smoking-cessation programs (

7), conduct psychotherapy (

8), and provide expert consultation to underserved populations, such as individuals in rural settings (

9,

10).

Most previous studies that examined the comparability of telephone and face-to-face interviewing have contrasted the relative prevalence rates of disorder associated with the two assessment procedures. Given similar rates of disorder for the two methods, it has been concluded that the methods are comparable (

11–

13). A more rigorous test of the comparability of the two assessment methods is to repeat the interview by using both telephone and face-to-face procedures. A few studies have adopted this approach. Wells et al. (

14) reinterviewed over the telephone 230 adults who had been interviewed face-to-face 3 months earlier as part of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Diagnostic agreement for depression (major depression and dysthymia) was fair (kappa=0.57). The authors concluded that the telephone interview had acceptable agreement with the original “gold standard” face-to-face interview and that no evidence suggested that one method resulted in more positive reports regarding depression. Paulsen et al. (

15) compared the reliability of lifetime anxiety disorders in 39 probands who initially had been interviewed face-to-face and were reinterviewed by telephone 12–19 months later. Interrater agreement ranged from good to excellent (kappa=0.69–0.84). Given the long interval between interviews, reliability may have been attenuated by change in the subjects' clinical status. In the present study, the interval between test-retest assessments was evaluated as one of the measures that may affect agreement.

METHOD

Subjects and Procedures

The current study was conducted in the context of an ongoing follow-up of participants from the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project. Extensive data have been collected previously from these individuals on two separate occasions while they were in high school (14–18 years of age). A detailed description of the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project is provided elsewhere (

19).

Subjects from the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project were invited to participate in a third wave of diagnostic assessments at age 24, which included structured psychiatric interviews to assess axis I and II disorders. Written informed consent was obtained after the procedures had been fully described. For the current study, 60 subjects who were residing in the local area were chosen to be interviewed both face-to-face and over the telephone regarding axis I disorders; an additional 60 subjects were chosen to be interviewed twice regarding axis II disorders. To guarantee an adequate representation of various psychiatric disorders, in each group of 60 participants, 20 were selected on the basis of a prior diagnosis of major depression, 20 were selected on the basis of a prior psychiatric disorder other than depression, and 20 had no diagnosed psychopathology. Of the 40 subjects selected because of a psychiatric disorder other than major depressive disorder, rates of disorder were as follows: substance use disorder (42.5%, N=17), adjustment disorder (32.5%, N=13), anxiety disorder (22.5%, N=9), disruptive behavior disorder (12.5%, N=5), dysthymia (7.5%, N=3), and an eating disorder (2.5%, N=1). There was no overlap between subjects who repeated the axis I interview and those who repeated the axis II interview. Fifty percent of the subjects participated in the face-to-face interview first, and 50% were interviewed by telephone first. The median duration between the two axis I interviews was 14 days (mean=22.5, range=2–92). Median duration between axis II interviews was 12 days (mean=16.8, range=1–55).

Seventy (58.3%) of the subjects were young women. The mean age at the time of interview was 24.4 years (SD=0.3). The vast majority (95.8%, N=115) identified themselves as Caucasian. Over two-thirds had either a high school diploma (67.5%, N=81) or a General Equivalency Diploma (2.6%, N=3), and 21.7% (N=26) had gone on to receive a bachelor's degree. Eighty percent (N=96) were working, 10.0% (N=12) were homemakers, and 3.3% (N=4) were students. The majority (55.0%, N=66) were single, 40.8% (N=49) were married, and 4.2% (N=5) were separated or divorced. The median household income was between $10,000 and $14,999.

Diagnostic Interviews

Assessment of axis I disorders. To cover the period between the previous assessment and the current study, the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (

20) was administered to each participant. This methodology provided detailed information about the longitudinal course of all disorders that were present at the previous assessment. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation also probed for the occurrence of new disorders since the previous assessment. To maintain diagnostic continuity with the first two assessments, a modified version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (KIDDIE-SADS) (

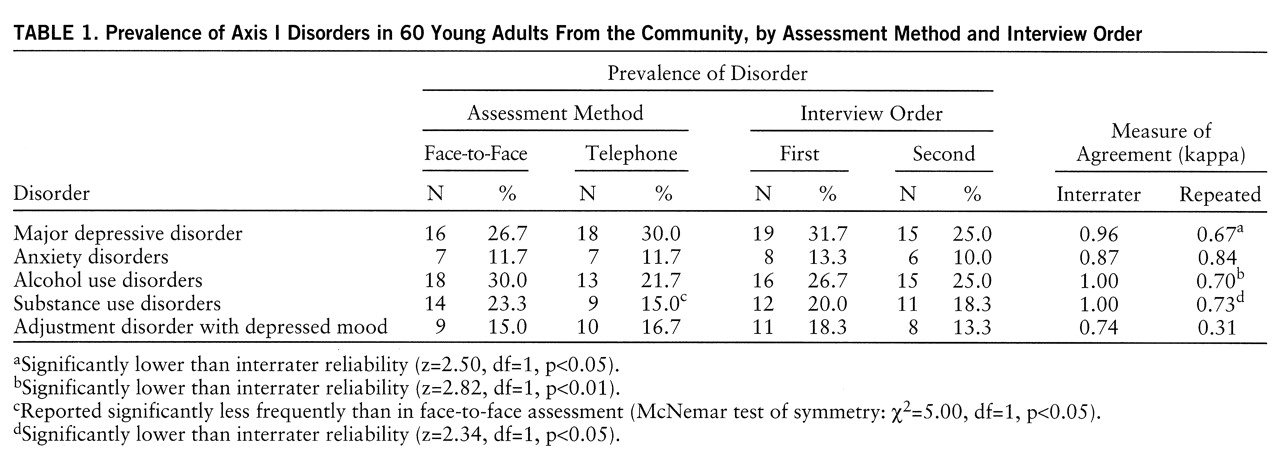

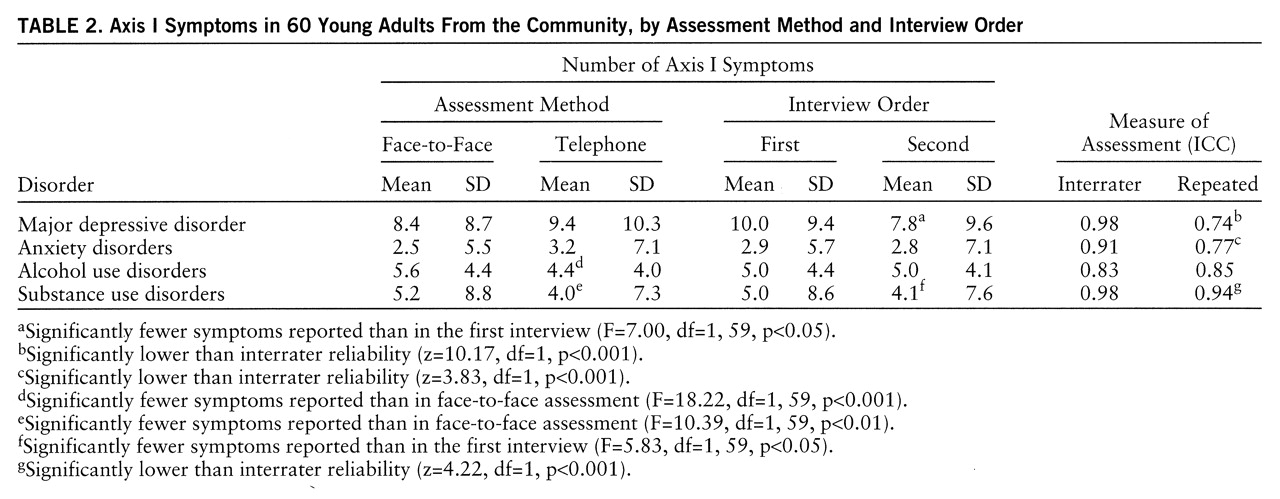

21) that combined features of the epidemiologic and present episode versions was used to assess axis I disorders that began in the interval before the current study. Additional questions were added to 1) assess disorders that were not previously examined (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD] and somatoform disorders), 2) reflect the adult presentations of disorders, and 3) incorporate changes associated with DSM-IV. In the present study, we focus on DSM-IV disorders or disorder categories that had prevalence rates greater than 5%. This included major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders (most often PTSD or panic disorder), alcohol use disorders (dependence and abuse), substance use disorders (most often cannabis abuse or dependence), and adjustment disorder with depressed mood.

Assessment of axis II disorders. The Personality Disorder Examination (

22) was used to assess all axis II disorders. The Personality Disorder Examination, which is organized according to issues (work, self, interpersonal relations, affect, reality testing, impulse control) usually took 1–2 hours to administer. When an item was endorsed, specific examples were solicited to rate the trait (0=behavior or trait absent or normal, 1=exaggerated or accentuated, 2=criterion level or pathological). In general, traits needed to be present for 5 years to meet diagnostic criteria. A detailed scoring manual was available that defined the scope and meaning of each item. The Personality Disorder Examination has been found to be among the most reliable assessments of axis II disorders and to be less influenced by concurrent depression or anxiety levels than other assessment methods (

23). Items that assessed the provisional disorders of self-defeating and sadistic personality disorder were not included. With the assistance of one of the interview's authors (Dr. Loranger), 20 items were added to the interview—which was originally developed to assess DSM-III-R criteria—to assess changes in criteria associated with DSM-IV (all forms used in this study are available from Dr. Rohde upon request).

Interviewer Training

Six diagnostic interviewers (five women, one man; five with master's or doctoral degrees in clinical or counseling psychology) were carefully trained in an extensive didactic and experiential course in interviewing. Before collecting data, interviewers were required to demonstrate a minimum kappa of 0.80 across all symptoms for at least two consecutive training interviews. In the first interview, the trainee scored diagnostic data collected by an experienced interviewer (either live or from recording). In the second training interview, the trainee conducted a live interview, while an experienced interviewer independently observed and scored diagnostic data. During data collection, biweekly discussion sessions were held between the supervisor and the interviewers to review interview procedures and diagnostic criteria. All interviews were audiotaped or videotaped, and a randomly selected subset were rated by a second experienced interviewer.

Statistical Analysis

Two types of reliability were examined: the degree of agreement between telephone and face-to-face interviews was contrasted with interrater reliabilities, in which a second interviewer made psychiatric ratings on the basis of reviewing a recording of the original interview. Fifty percent of the interviews (i.e., 60 KIDDIE-SADS and 60 Personality Disorder Examination interviews) were coded for interrater reliability.

Diagnostic reliability was evaluated by the kappa statistic (

24), which assesses the degree of agreement for a dichotomous measure controlling for chance. Kappas less than 0.40 are generally considered poor, values that exceed 0.60 are good, and kappas above 0.75 or 0.80 are considered excellent (

25). In addition to the kappa statistic, McNemar's chi-square (

26) was computed to examine the tendency to report fewer symptoms with one method of interviewing than the other. Differences in kappa values were examined by using the z test (

25).

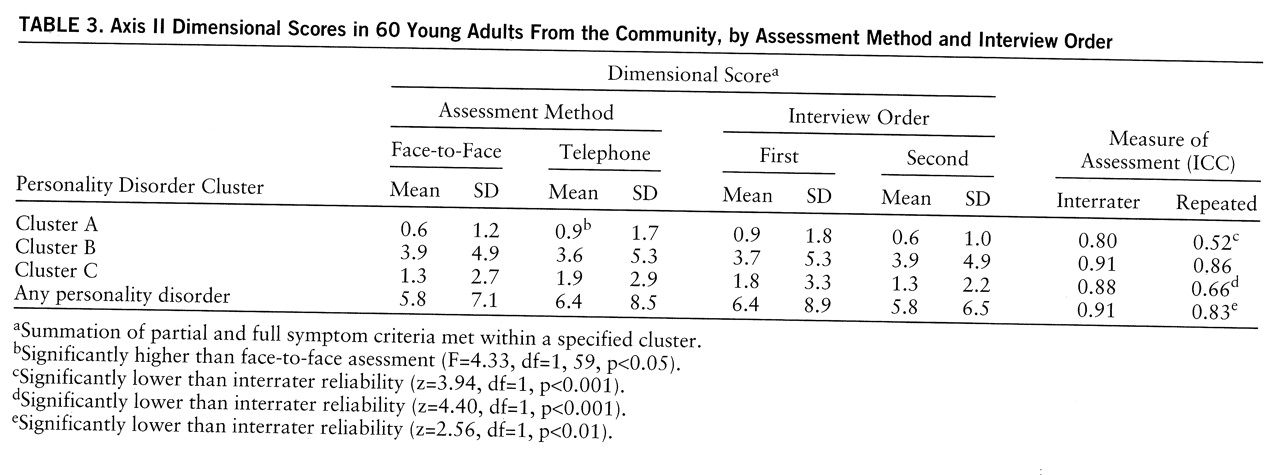

Base rates were too low to examine specific axis II disorders. Therefore, agreement regarding axis II disorders was examined by using dimensional scores (i.e., summation of partial and full symptom criteria), which were computed for the three personality disorder clusters (cluster A: paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders; cluster B: antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders; cluster C: avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, and passive-aggressive personality disorders) as well as for all personality disorders. Agreement in the continuous dimensional scores, as well as the mean number of individual axis I symptoms, was examined by using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (

27). All statistical tests were two-tailed.

DISCUSSION

On the basis of the results presented here, is it possible to conclude that diagnostic information from telephone interviews is comparable to data obtained from a face-to-face assessment? The answer appears to depend on the specific disorder that is being assessed. Test-retest agreement, in which assessment method, interviewers, informant report, and time interval varied, was contrasted with interrater agreement, in which all factors were held constant except interpretation of the subject's report by the interviewer. It was presumed that interrater agreement represented the upper limit of possible agreement between the telephone and face-to-face procedures. Given that agreement was excellent for both the interrater and test-retest conditions, one can assert with considerable confidence that the assessment of anxiety disorders is unaffected by interview method. Assessing major depressive disorder by the telephone also appears justified, although support was not as strong as for anxiety disorders.

The present findings provided strong support for the validity of the axis II telephone assessment format. There was no indication that significantly less axis II psychopathology was reported over the telephone, and excellent test-retest reliability was obtained for “any personality disorder” and for cluster B (i.e., antisocial, borderline, histrionic, narcissistic) personality disorders, which were the most frequently reported and probably included some of the most behaviorally anchored items.

The reliability of the assessment of adjustment disorders with depressed mood, which are usually brief and remit spontaneously, was problematic. However, discrepancies regarding this diagnosis did not appear to be due to either assessment method or order effects. Disagreements probably emerged because of the overlap with major depressive disorder at the upper end of adjustment disorder and with either depression not otherwise specified or no diagnosis at the lower end of the continuum.

The only area of potential concern for telephone assessment involved the diagnosis of alcohol and substance use disorders. Although the repeated interview kappas indicated very good levels of comparability across assessment methods, the telephone condition elicited fewer symptoms of alcohol and substance use disorders. When scheduling the telephone assessment, the interviewer tried to set up a time when the participant could talk in private. This was not always possible. In 19 of the telephone interviews (12 KIDDIE-SADS and seven Personality Disorder Examination interviews), someone else was present during the assessment: child (N=13), spouse or partner (N=4), parent (N=1), or other (N=1). The presence of someone else may have hindered the participant's comfort in reporting drug use. If at all possible, clinicians who work with patients by telephone should schedule a time when they will have complete privacy. Interviewers who use either assessment method need to be especially sensitive to developing rapport with subjects before gathering information regarding drug and alcohol use and also need to convey to the individual the degree to which this information will remain confidential.

While the present findings provide qualified justification for the assumption that comparable data are obtained in telephone and face-to-face assessment formats, there are some concerns with the telephone interview data that temper our enthusiasm. These concerns, however, are not sufficient to override the economic and logistic advantages of telephone interviewing in research, especially the ability of telephone interviewing to maximize participation.

There were small but consistent trends for lower rates of axis I disorders and axis II cluster A psychopathology to be reported in the second interview. Fenig et al. (

28) suggested that lower reporting of disorder in the second interview may be due to subject confusion and speculation regarding the purpose of the second interview, desire on the part of the subject to create a more favorable impression at the second assessment, and even the therapeutic effects of the first interview. The present results indicate that the nature of symptoms being assessed has an impact on the order effect. A reduction in reporting from first to second interview was seen most strongly for symptoms of major depressive disorder and substance use disorders.

With only one possible exception, gender did not moderate the degree of agreement across assessment methods. Also, within the time range that was examined, a greater interval between assessments only significantly reduced agreement levels in one instance.

Several limitations to the present study should be noted. First, we are unable to draw any conclusions about disorders with low base rates in the cohort (e.g., schizophrenia, somatoform disorders). Second, we could not evaluate the impact of sex of the interviewer. Third, it is unknown if these findings will generalize to younger and older individuals. Finally, because of the predominancy of Caucasians in the study, the impact of ethnic factors could not be examined. Underreporting of sensitive information on telephone interviews may be greater for African Americans and Hispanics than for Caucasians (

12,

29).

There are many positive aspects to the present study. Subjects were interviewed twice in a counterbalanced design, and most of the major disorders were covered. The use of a nonpatient cohort also represents a strength, since disorders in community samples are milder and therefore less consistently reported (

30). Psychiatric problems in community samples are more likely to hover around the threshold of diagnosis, which would require the interviewer to make the difficult decision of whether the condition represents a normal variation of functioning or an actual disorder. Thus, the present study is a particularly rigorous test of the comparability of telephone and face-to-face assessment procedures.