The quantity of information available to scholars concerning how Sigmund Freud actually conducted his psychoanalyses has been steadily growing for several decades, but the location and compilation of these data have not been simple tasks. Since Freud did not allow others to observe his clinical work, reliable information about his actual practices can come only from Freud or his analysands. Freud's published work includes his notes in the famous case of the Rat Man (1, pp. 259–318), but otherwise the standard edition of Freud's works contains little material describing how Freud actually treated analysands or how he conducted his relations with them. A large number of Freud's letters became available for review at the Library of Congress in the 1980s, but the relative illegibility of his gothic script and the suppression of some important passages remained as obstacles. These obstacles have been partly overcome in the past 4 years by the publication of his complete correspondence with Ernest Jones (

2) and much of his correspondence with Sandor Ferenczi (

3,

4).

Data from analysands are found in much more scattered and diverse places. Published accounts, including book-length memoirs, autobiographies, and shorter reports from more than 20 analysands, appeared by the end of the 1980s. Unpublished accounts, reports and transcripts of interviews of analysands, and letters written by analysands have gradually emerged. However, no index or bibliography of these materials has ever been available.

Past attempts to review Freud's methods have been limited by the sources that were used. One of Freud's biographers, Gay (

5), noted several cases in which Freud's actual methods differed from his recommendations: the preexisting friendships in the cases of Max Eitingon and Sandor Ferenczi; Freud's expressiveness and warmth in the cases of the Rat Man, the Wolf Man, and Jeanne Lampl-de Groot; and the entire analysis of Freud's daughter Anna. Gay acknowledged “Freud's sovereign readiness to disregard his own rules”

(5, p. 292) but noted, “It was the rules that Freud laid down for his craft, far more than his license in interpreting them for himself, that would make the difference for psychoanalysis”

(5, p. 292). Jones reported that Freud had difficulty in keeping confidences, but he did not specify whether the confidences in question had been given by analysands

(6, p. 409). Roazen's work (

7,

8) is based on his interviews of as many as 25 Freud analysands; it contains much material pertaining to a number of cases but no attempt at a systematic compilation.

Ruitenbeek (

9) concluded that Freud had related to his analysands in unorthodox ways, but he did not clearly document his sources. Using case material from the standard edition and limited additional sources (

10,

11), Glenn (

12) noted that “Freud at times behaved contrary to the principles that he laid down, even

after espousing them.”

Published reports of attempts to gather historical data from a series of Freud cases and bring these data to bear on technical questions have been few in number. Lipton (

13–

16) contributed a series of papers in which he considered technical implications of Freud's actual methods. In a 1977 paper largely devoted to the Rat Man case (

14), Lipton did include a list of seven additional analysands (Joseph Wortis, Hilda Doolittle, Smiley Blanton, Joan Riviere, Roy Grinker, Raymond de Saussure, and Alix Strachey), citing their published descriptions, but only to “demonstrate the cordial relationships which Freud established with his patients.” Lipton (

15) reached the conclusion that Freud “regularly established and maintained a personal relationship with the patient which he took for granted and excluded from technique.” Momigliano (

17) made use of published reports from as many as 14 people who had undergone brief didactic analyses with Freud between 1920 and 1938. She noted that Freud seemed not to have observed his recommendations in his daily work, and she raised the question, “Was Freud a Freudian?” but she explicitly declined to answer it. Mahony (

18) briefly described two cases (Elma Palos and Horace Frink), raising the question of whether they should be used in the teaching of psychoanalysis. Gabbard (

19) included eight Freud cases (Elma Palos, Sandor Ferenczi, Loe Kann, Horace Frink, Marie Bonaparte, Alix Strachey, James Strachey, and Anna Freud) in a discussion of boundary violations in the early history of psychoanalysis; he summarized, “Freud and his early disciples indulged in a good deal of trial and error as they evolved psychoanalytic technique” (p. 1115). Lohser and Newton (

20) reviewed five cases (Abram Kardiner, Hilda Doolittle, Joseph Wortis, John Dorsey, and Smiley Blanton) in an attempt to reconstruct how Freud actually practiced. They concluded that Freud's actual methods had been inadequately studied and widely misunderstood and that Freud had used departures from neutrality and opacity to good effect in accomplishing what these authors believed was Freud's principal task—to make the unconscious conscious.

In his 1991 review of Freud's technical papers, Ellman (

21) noted that many reports from Freud's analysands had reached publication. Without listing or reviewing these, Ellman simply stated that “Freud was a highly variable analyst who frequently disregarded (or violated) his own suggestions” and “when one looks at Freud's behavior with patients, it is difficult to reconcile some of his conduct with his written work.”

The authors of four papers published in the last 5 years each used emerging historical sources to explore Freud's conduct of a single psychoanalytic case. One of us described Freud's psychoanalyses of “A.B.,” a young psychotic man (

22), and Albert Hirst (

23), noting deviations from anonymity and neutrality in each case. Warner (

24) drew on correspondence and other archival material in his examination of the case of Horace Frink. Finally, Kris (

25) used the published Freud-Jones correspondence as the historical source for a description and discussion of Freud's psychoanalysis of Joan Riviere. Without reviewing any other cases, Kris noted that Freud's conduct in the case was very different from his published recommendations. Kris viewed Freud's failure to acknowledge this disparity as in part “the result of a divided allegiance between his sense of what was needed by his patients and his determination to promote and preserve the scientific standing of psychoanalysis”

(25, p. 662).

Sigmund Freud's technical recommendations and theoretical contributions have retained an important influence in American psychiatry. They are given substantial emphasis in discussions of psychotherapy in both of the most prominent American textbooks of general psychiatry (

26–

29). As recently as 1993, Freud's 1915 technical paper “Observations on Transference-Love” was reprinted in its entirety in the American Psychiatric Press's

Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, with Glen Gabbard's prefatory statement that it “still reigns as the state-of-the-art treatise on its subject” (

30).

To the extent that psychiatrists use or rely on Freud's contributions, they will benefit from an understanding of the relationship between these contributions and Freud's actual clinical activities and experiences. To what extent were his technical recommendations rooted in actual practice? Because Freud did not engage in any extensive direct observation of the psychoanalytic work of others, it was only in his own psychoanalytic practice that he could make observations and conduct trials and evaluations of his technical recommendations. Therefore, a systematic historical review of the methods he actually used in his psychoanalytic practice is currently highly relevant to American psychiatry.

From published and unpublished sources we gathered extensive information on Sigmund Freud's practice of psychoanalysis in his mature years. For the period 1907–1939 we found data on 43 of his analytic cases. There is much more information for some of these cases than for others, but in each case some sense of the nature of Freud's management of his relationship with his analysand emerges. At their best, these sources provide many particulars—Freud's various expressions toward analysands, his responses to them, his activities and decisions that affected them. They have the qualities of historical materials—vivid detail here and there, frustrating gaps elsewhere.

What emerges can be seen as a survey of Freud's clinical and experimental activity during his mature years. In this paper we review Freud's published recommendations as they pertain to anonymity, neutrality, and confidentiality. Next, we systematically describe Freud's actual practices in 43 cases and provide accounts of five illustrative cases. Finally, we discuss the implications of our findings.

FREUD'S RECOMMENDATIONS

Freud published comprehensive recommendations regarding how psychoanalysts

should conduct themselves in their relationships with analysands. Three of the most basic issues addressed by Freud's recommendations concern anonymity, neutrality, and confidentiality. Pulver (

31) reviewed each of these three topics.

First, with regard to anonymity, Freud recommended that the analyst not reveal his own emotional reactions or discuss his own experiences (32, pp. 117–118; 33, p. 125; 34, pp. 225, 227; 35, p. 175). Freud viewed any previous acquaintance with the patient or relation with the patient or the patient's family as a serious disadvantage (33, p. 125; 36, p. 461).

Second, with regard to neutrality, Freud recommended that the analyst not give the patient directions concerning choices in the patient's life nor assume the role of teacher or mentor (32, pp. 118–120; 37, p. 433; 38, p. 164; 39, p. 232; 35, p. 175). Finally, Freud recommended that the analyst preserve the patient's confidentiality (33, pp. 136–137; 36, p. 460; 35, p. 173).

These recommendations are familiar to experienced clinicians. They are fundamental to Freud's technical contributions. None of them was ever retracted or substantially modified in any of Freud's writings.

As Freud acknowledged in 1928

(6, p. 241), “The `Recommendations on Technique' I wrote long ago were essentially of a negative nature. I considered the most important thing was to emphasize what one should

not do, and to point out the temptations in directions contrary to analysis.” His recommendations concerning the three issues of anonymity, neutrality, and confidentiality were both negative and relatively simple. Deviations from such simple, negative recommendations can be rather readily identified in historical sources. Systematic historical study of deviations from (or adherence to) more complex,

positive recommendations would be vastly more difficult.

SOURCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF CASES

There are 43 cases in the period 1907–1939 for which we were able to find some information on Freud's actual conduct of the psychoanalysis. Published and unpublished sources in these cases included reports or autobiographies by analysands in 23 cases, letters written by analysands in 16 cases, interviews of analysands in 19 cases, letters written by Freud in 25 cases, Freud's published works in 10 cases, and clinical records from subsequent treatment in two cases. In 19 cases, indirect sources contributed additional information. (A fully referenced draft of this paper, including 353 references, is available from NAPS, c/o Microfiche Publications, P.O. Box 3513, Grand Central Station, New York, NY 10163-3513.) The information in most cases was derived from multiple sources. In this series we have included only the cases for which information was available either directly from Freud or from the analysand.

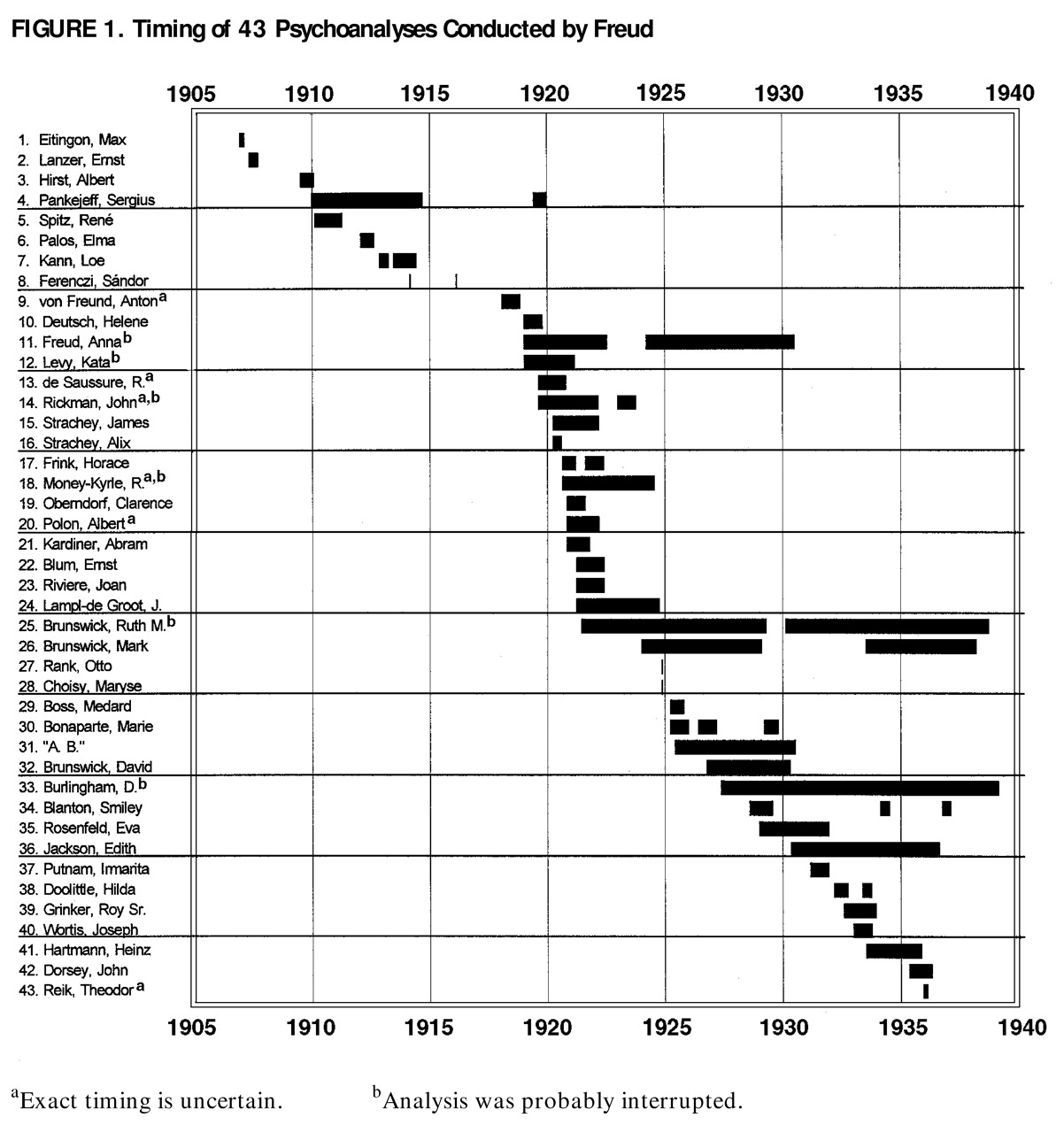

The timing of these cases is displayed in

figure 1. This graphic display indicates the extent of our sampling of Freud's work. Especially when seen in terms of what is known of Freud's caseload (2–4; 6; 7; 40; 41, pp. 272, 275, 278; 42), this collection of cases is extensive. It probably encompasses a majority of Freud's analytic

hours in these years, but not necessarily a majority of Freud's

cases.

The basic characteristics of these analyses are as follows. Of the total of 43 analysands, 27 were male and 16 were female. Ten of these psychoanalyses were clinical, 19 were didactic, and 14 were both. German was the language used in 24 of these cases, English (or probably English) was used in 14, and the remaining five cases involved mixed use of the two languages. The median duration was 26 months, 18 months for men and 38 months for women. The ages of the analysands at the initial hour ranged from 22 to 49 years, and the median was 33.

FINDINGS

There is little question that Freud considered each of these cases to be a valid attempt at psychoanalysis. He always used the term “psychoanalysis” whenever he referred to any of them. He used eight of them as examples in his published writings. He approved all of the trainees in the group to practice psychoanalysis, and his clinical activities in these years (except for the 1-hour afternoon consultations that he offered in the Vienna medical tradition) were composed exclusively of psychoanalyses

(43, p. 260).

Nevertheless, in all 43 cases Freud deviated from strict anonymity and expressed his own feelings, attitudes, and experiences. Freud's expressions included his feelings toward the analysands, his worries about issues in his own life and family, and his attitudes, tastes, and prejudices. Likewise, in 31 (72%) of the cases, Freud's participation in extra-analytic relations with analysands and/or his selection of analysands who already had important connections to himself or his family helped to eliminate anonymity. These various expressions and relations obviated the anonymity and opacity prescribed in Freud's published works and gave each analysand a rich view of the real Freud.

Freud's directives to his analysands also implicitly communicated his feelings. As will be illustrated in the cases described, Freud breached his repeated recommendation against directiveness by the analyst in 37 (86%) of these cases. Freud's directiveness spanned this entire period and was as much a feature of his work in one time as in another.

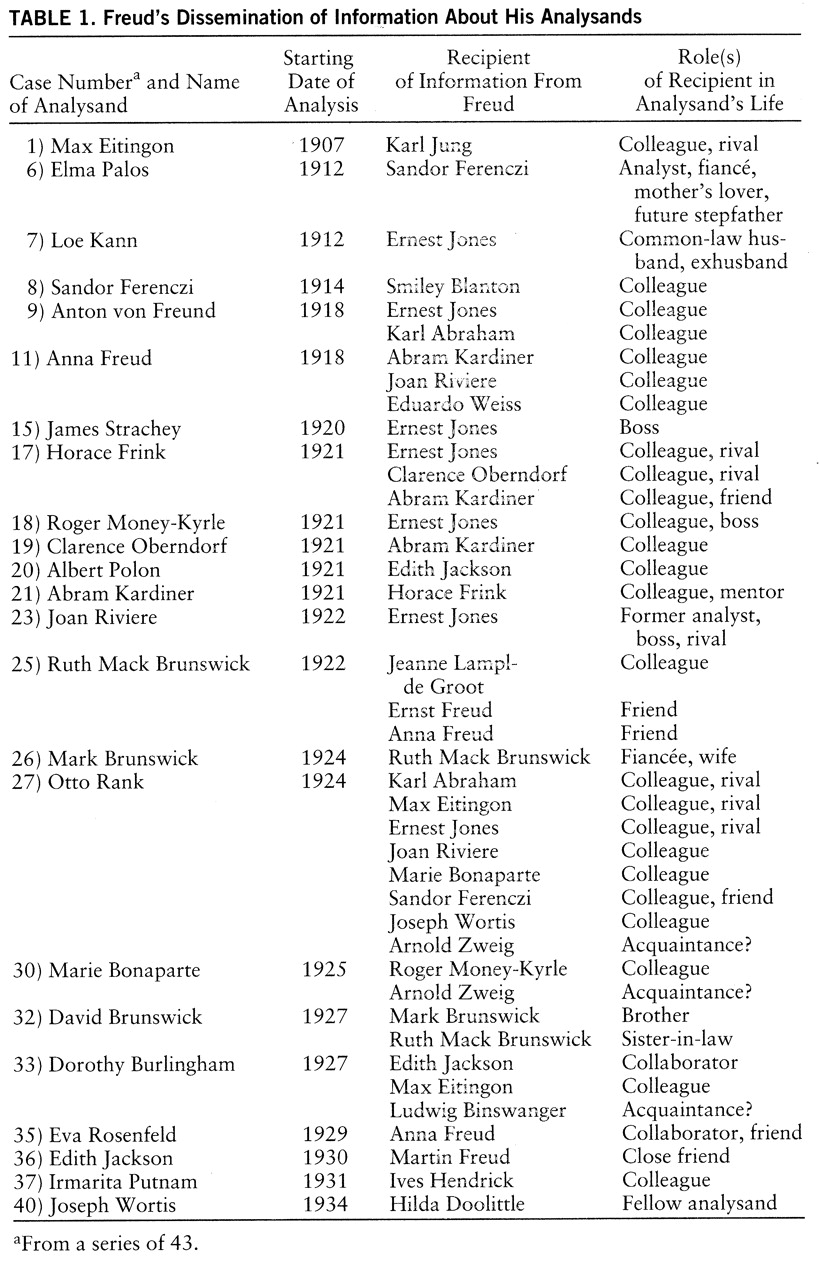

Freud communicated with others about analysands in 23 (53%) of these cases. These communications were to people known to the analysand and included Freud's identification of the analysand. This group of 23 does not include Freud's published cases of unidentified analysands, such as the Rat Man, the Wolf Man, and A.B. (

22), nor does it include Freud's communications with referring practitioners or consultants. We tabulated deviations from expected confidentiality only in cases where we found clear evidence. This is the most unambiguously documented finding in our study; most of these breaches of confidentiality can be read in Freud's own handwriting. A listing of these 23 cases with the respective recipients of information is contained in

table 1. These communications occurred in cases throughout the years 1907–1939. An interesting additional finding is that no fewer than 20 (47%) of the 43 analysands in our series received information from Freud about other analysands.

FIVE ILLUSTRATIVE CASES

Albert Hirst

Albert Hirst (case 3) entered analysis with Freud in the autumn of 1909 at the age of 22. His unpublished autobiography and transcripts of his interviews with K.R. Eissler are the principal sources in his case (

23). He wanted help with increasing symptoms of depression and longstanding sexual difficulties. He had been treated by Freud for 2 weeks in the spring of 1903 after a suicide gesture. He had known Freud and Freud's family from the beginning of his life. Hirst's mother, KÄthe Eckstein, was the elder sister of Freud's analysand Emma Eckstein. The Eckstein and Freud families often took vacations together (

44). His elder sister, Ada, had also made a brief attempt at analysis with Freud.

Hirst's difficulties were characterized by a lack of self-confidence. Although he was a gifted Gymnasium student and achieved high grades, he typically experienced terror in anticipation of examinations, to the point of vomiting and total insomnia. He consistently procrastinated in response to any duty or task. He was unable to apply himself as a university student, and he withdrew after a year. His sexual difficulties included a general feeling of incompetence and feelings of guilt and shame about his masturbation. Most important to him was his inability to ejaculate inside a woman. He was chronically preoccupied with unrequited love for a young woman he had met in Gymnasium, and her explicit and humiliating rejection precipitated his crisis. As his mood deteriorated, he blamed himself for all his difficulties. He saw himself as selfish, incompetent, and completely inferior to his family. He doubted the sincerity and validity of all of his thoughts and feelings. He felt totally isolated.

Freud reassured Hirst about the inevitability and harmlessness of his masturbation. He often encouraged Hirst and expressed appreciation for Hirst's intelligence, his talent in poetry, and his business skills. Freud told Hirst that Hirst's feelings were sincere and real. He praised Hirst's own interpretations of dreams and his discussions of various novels.

Freud freely discussed his own feelings, experiences, and opinions. He told Hirst that he had been annoyed by the absence of public toilets in New York City and that he generally disapproved of the United States, but he also related the American success story of his Czech former cook. Freud took pains to describe to Hirst his role in the discovery of cocaine as a local anesthetic and discussed his views on sexual morality and marriage at length.

Freud pointedly encouraged Hirst in the pursuit of sexual experiences with women. Eventually, Hirst did succeed at intercourse. Freud expressed profuse pleasure and prescribed a vaginal suppository as a contraceptive. Later, Hirst told Freud about a young woman who was encouraging him but was not attractive to him. When Freud insisted that Hirst proceed, Hirst found himself once more unable to ejaculate.

Freud was directive with Hirst on several additional issues. He favored a business career for Hirst, as opposed to politics, the law, or writing. He discouraged Hirst's immigration to the United States and proposed South America instead.

From Freud, Hirst learned about his sister Ada's abortive psychoanalysis. Freud gave an appraisal of Ada as less gifted than Hirst. About Hirst's aunt, Emma Eckstein, another analysand, Freud was even more informative. When Emma relapsed during Hirst's analysis, she viewed her new symptoms as organic; Freud told Hirst that her symptoms were neurotic. Freud even told Hirst that Freud's decision to terminate his involvement in Emma's treatment was an angry response to her consultation with another physician.

Elma Palos

Elma Palos (case 6) began psychoanalysis with Freud in January 1912 at the age of 24. She was referred to Freud by Sandor Ferenczi, and the correspondence between the two men provides information on her treatment (

3,

4). Ferenczi had begun an analysis of Elma in July 1911. At that point Ferenczi, aged 38, was in the midst of a long affair with her mother, Gizella, 48, whom he had previously analyzed and introduced to Freud. Freud had ventured a diagnosis of dementia praecox for Elma as early as February 1911, although the extent of his examination of Elma at that time is unclear. Elma's initial difficulties seem to have involved depression, possibly precipitated by difficulties with suitors, one of whom killed himself in October 1911. By November 14, Ferenczi was writing to Freud about his wishes to marry Elma instead of Gizella. By Jan. 1, 1912, Ferenczi had begun to recognize that “the issue here should be one not of marriage but of the treatment of an illness.” Ferenczi had been continuing his psychoanalysis of Elma through all of these events, without objections from Freud, but he now implored Freud to take over Elma's analysis immediately. He had already arranged all the particulars with Elma and Gizella, including the fee.

Freud did agree, after remarking, “In this humor, a woman can hardly be woo'd!” Note that this remark, like all previous references to Elma and her treatment in Freud's letters to Ferenczi, addressed Ferenczi's interests, not Elma's. After beginning Elma's analysis, Freud began to report to Ferenczi on his findings, including his formulation of Elma's feelings for Ferenczi and his conclusions about her suitability as a wife. Ferenczi made clear to Freud that he had not decided what to do about the marriage and that he would “make everything dependent on the results of the analysis.” Ferenczi felt “totally dominated by the reports that you give me about Elma,” and he tried to describe all of his feelings to Freud, even his unsatisfying renewal of his sexual relationship with Gizella at this time.

Freud acknowledged that for Ferenczi a decision would be possible only after the end of Elma's treatment and that at some point Freud would be “able to pass judgment” on Elma. For her part, Elma wanted to know from Ferenczi exactly what Freud was writing about her. As of Jan. 20, 1912, Ferenczi was writing, in response to Freud's reports, that he was ready to give up the idea of marrying Elma, but he frequently vacillated thereafter. He and Freud arranged to meet secretly and discuss Elma. In March, Freud began to report progress in Elma's analysis. He suggested to Ferenczi that it be terminated at Easter. The two men agreed on this timing and began to plan a holiday together in Dalmatia. Elma wanted to have the treatment continue longer, but Freud and Ferenczi prevailed.

In November 1912, Ferenczi had given up the idea of marrying Elma, and the two men began to consider how to marry her off.

Ferenczi married Gizella in 1919, but in a 1922 letter to his friend George Groddeck (

45) he regretted his decision not to marry Elma and blamed Freud for it. In 1932 he wrote in his clinical diary that he was struck by “the ease with which Freud sacrifices the interests of women” (

46). It is clear from the correspondence that Freud used Elma's analysis to serve the interests of his friend Ferenczi and the psychoanalytic movement and that he never objected to Ferenczi's similar behavior.

Loe Kann

Loe Kann (case 7), the common-law wife of Ernest Jones, began her analysis with Freud in June 1912. An account of her analysis emerges from the Freud-Jones correspondence (

2). Loe was of Jewish ancestry and was born Louise Dorothea Kann in the Netherlands, but her precise age is not clear. (Jones himself was 33 at this time.) She had been suffering from abdominal pain and associated addiction to morphine (then legally available) and depression. She had moved from London to Toronto with Jones in 1908, and she became more and more isolated and unhappy there.

At the psychoanalytic congress in Weimar in September 1911, in her absence Jones requested that Freud take her into analysis. Freud agreed. Later he linked his willingness to his “deep personal interest” in Jones, as one of the “men who give me so much assistance and friendship.” In analysis, Freud found Loe very appealing. He wrote to Ferenczi that she was “extremely intelligent,” “a jewel,” and finally, “Loe has become extraordinarily dear to me, and I have produced with her a very warm feeling” (

3). By December 1912 he had brought Loe to meet his family in their apartment (

3). Loe and Anna Freud began a long friendship at this time (

47).

An interesting feature of this analysis was Freud's participation in Loe's medical treatment. Jones believed that a diagnosis of pyelonephritis had been established previously in London, and Loe concurred that her abdominal pains were basically organic. Freud favored a diagnosis of hysteria even after medical consultation in Vienna yielded a contrary opinion. He had heated disagreements with Loe about this issue, to the point that in the fifth month of the analysis she felt “forced, bullied, and teased” by Freud. He conducted a urinalysis and arranged radiological and, finally, surgical evaluation, which confirmed Jones's, and Loe's, view.

Throughout this analysis, Freud provided Jones with details of Loe's progress and, especially, her feelings about Jones. Jones and Freud had hoped that her sexual responsiveness would improve as a result of the analysis. In January 1913, Freud advised both Loe and Jones to refrain from sexual relations. Shortly thereafter Loe discovered that Jones had been unfaithful, and she ended their long affair. Despite this change, Freud continued to keep Jones informed of Loe's feelings toward him, her dating activity, and Jones's chances for a reconciliation. Freud predicted a reconciliation, but it never occurred.

In June 1914, Loe married a young American man in Budapest; Freud, Rank, and Ferenczi were present as official witnesses. She terminated her analysis shortly thereafter. She had been able to reduce, but not eliminate, her use of morphine.

Anna Freud

Anna Freud (case 11), Freud's youngest child, entered analysis with him in 1918 at the age of 23. Little is known about this analysis except what Young-Bruehl (

47) drew from Anna's correspondence and a few other sources. Until an interruption in 1922, Anna had 6 hours each week at 10:00 p.m. Another period of analysis began in 1924. Although other sources describe a complete cessation of the analysis after 1925, it is clear from her letters to Eva Rosenfeld that Anna was still in analysis with her father as of September 1929 (

48). In his September 1927 letter to Joan Riviere, Freud used the present tense in describing himself as Anna's “control analyst”

(41, p. 267). Until 1970 the identity of Anna's analyst was not generally known. When, as an adult, Peter Heller, a former analysand of Anna and a son-in-law of Dorothy Burlingham (another analysand of Sigmund Freud), asked Anna in Dorothy's presence who her analyst was, she exchanged knowing glances with Dorothy but remained silent (P. Heller, personal communication, April 6, 1991).

During the first period of his analysis of his daughter, Freud was also analyzing Abram Kardiner. In one of Kardiner's hours Freud raised the subject of Anna and her unmarried status, asking Kardiner for his theories. Kardiner had heard rumors that Anna was in analysis with her father, but he did not ask Freud about this. Kardiner believed that most of Freud's male followers had offered to become his son-in-law (

49).

Anna never married, and she remained tied to her father for the rest of his life as a companion, typist, collaborator, and nurse. Despite her lack of a university education, she was accepted as a psychoanalyst and attained prominence. What is remarkable about her analysis is its very existence. At its inception Freud was 62 years old. He considered this analysis to be valid enough for crucial use in two theoretical papers, “A Child Is Being Beaten” in 1919 (

50) and “Some Psychical Consequences of the Anatomical Distinction Between the Sexes” in 1925 (

51). In 1935 he described it as a success in a letter to Eduardo Weiss (

52).

Edith Banfield Jackson

Edith Jackson (case 36) began her analysis with Freud in January of 1930, at age 35. Her letters, especially to her sister Helen Jackson, are the principal source in her case (

53), together with a 1966 interview by Roazen (

8). She had been thoroughly trained as a pediatrician in the United States. She hoped for both clinical and didactic results, having suffered from loneliness and an inability to establish an intimate relationship. She found Freud extremely charming. Sometimes he would gently strike the couch with his hand. He discussed many things with her—his 1909 trip to the United States, Adler, Jung, Rank, Marianne Kris, and the opera

Don Giovanni (at times he would hum a few bars). Freud's dog was present in the consulting room, and when this chow had puppies, Freud gave one to Edith Jackson.

In one of the first few sessions, Freud presented a dream that Dorothy Burlingham, another analysand, had described to him, asking for her help in interpreting it. Later, at his direction, she began translating some of his writings, and he would use her analytic hours to review her translations. At one point Freud told her that he wished she would improve as quickly in the analysis as she had as a translator. At times she had as many as eight analytic hours with Freud each week, at a fee of $25 per session. She chose to begin her analysis in broken German, which Freud found intolerable; he soon chose to have her proceed in English. He forbade her to have sexual relations while in analysis.

Gradually Edith Jackson was drawn into Freud's circle. She met his wife and sister-in-law. She had social contact with most of Freud's other analysands of this period: Smiley Blanton, Dorothy Burlingham, Marie Bonaparte, Irma Putnam, Ruth Mack Brunswick and her husband Mark, Anna Freud, and Eva Rosenfeld. She followed Freud, at his invitation, to continue her analysis in Berlin and at Grundlsee. She donated $5,000 per year to establish a nursery school in collaboration with Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingham.

Early in the analysis Edith Jackson was stunned when Freud brought up her mother's suicide; he had learned about it not from her but from a source whom Freud refused to name. She began an exploration of this issue that included a review of her mother's diary, obtained from her sister.

In 1931 she met Freud's eldest son, Martin, at an analytic meeting. They became such close friends during her analysis that Martin's wife was convinced that they were having an affair (

54). Martin did write many letters to her, reporting at one point that his wife was nearly insane and that living with her was impossible (

53). At times Freud provided his son with information about Edith Jackson and her intentions concerning him. In a 1936 letter to her (

55), Freud described the difficulties that another analysand, Albert Polon, had encountered in a relationship with a young woman during his analysis with Freud.

Despite her wish for an intimate relationship with a man, Edith Jackson never married. Although Freud thought he had helped her, she was uncertain about this (

8). She did return to her career in psychiatry in the United States, and after 10 lackluster years, in 1946 she began to perform remarkably well (

56).

CONCLUSIONS

The limitations of this study must be kept firmly in mind. Any conclusions concerning the effectiveness of the methods Freud actually used in these cases would require much more detailed and comprehensive biographical study of these analysands. Any conclusions concerning Freud's reasons or motives for acting as he did are beyond the scope of this study; this question would require much more detailed biographical study of Freud. Finally, any conclusions concerning the effectiveness of Freud's recommended technique of psychoanalysis are obviously beyond the scope of this study.

Throughout the period of this study, 1907 to 1939, Freud consistently deviated from his published recommendations on psychoanalytic technique. Indeed, his actual method could be seen as a quite different process, characterized by expressiveness and a tendency to be forcefully directive. It might be tempting to see his recommended technique as superior to his actual method. Such a view would be rather more moralistic than scientific. Freud's use of self-disclosures and directives may more closely resemble the techniques that current psychotherapy research has demonstrated to be most effective than does his recommended technique (

57,

58).

Concerning Freud's recommendation that the analyst remain anonymous (a blank screen, as it were), his self-revelations in 100% of these cases and his participation in extra-analytic relations in 72% raise important questions. These deviations had implications for the development of each analysand's emotional experience of Freud and feelings toward him—the transference. Freud's recommendations to maintain an uncontaminated transference through anonymity have by no means been unanimously endorsed by subsequent contributors. (The literature on this issue is simply too vast to review here.) The feasibility and effectiveness of the anonymous approach Freud recommended deserve to be scientifically tested. One point clearly established by our study is that Freud's psychoanalytic work was not such a test. Instead, Freud's personal expressiveness and extra-analytic involvements invite consideration of each of these 43 analyses as a unique emotional and personal interaction between Freud and his analysand. Perhaps each outcome should be attributed more to these interactions and their qualities—warmth, support, acceptance, trust (or conversely, coldness, rejection, etc.)—than to insights achieved through an interpretive exploration of the transference.

= Freud's deviations from neutrality in 86% of these cases likewise require attention. Obviously, because of Freud's stature and authority in these years, his directions and influence must have had a substantial impact on each analysand's experience.

= Concerning confidentiality, Freud's communications to others about his analysands do raise both ethical and technical issues. Crucial to consideration of the ethical issues is the question of the consent of the analysand. For most of these cases, this is unknown. Analysands such as Abram Kardiner (

49,

59), Mark Brunswick (

8), and Elma Palos (

3,

4) clearly did

not consent to these communications in advance. Of course, it is possible that in each of the other cases Freud had obtained the analysand's consent. It is also possible that analysands knew of Freud's pattern of indiscretion and therefore had given implied consent simply by entering analysis with him. Jones's observation that Freud “had indeed the reputation of being distinctly indiscrete” (

6) suggests this possibility, as does our finding that 20 analysands in our series (47%) received information from Freud about other analysands.

= Heretofore, to the extent that Freud's recommendations on technique could be seen as a description of his clinical practice, his prescribed methods and his theoretical conclusions could be seen as supporting each other. Freud's theoretical conclusions could be considered to be validated by having been reached through the consistent use of an objectively defined set of methods. This proposition is not true. Freud's technical recommendations remain remarkably influential in American psychiatry. They form an internally consistent, logical system. But whenever they are cited to address issues in the conduct of psychoanalysis or psychotherapy, we should be aware that Freud did not actually test them. Freud's actual method was never explicitly described in his writings and cannot be replicated.