The past decade has seen dramatic changes in the role played by psychiatric hospitals in the care of patients (

1). Patients who would have remained hospitalized for weeks, months, or even years are now treated mostly or entirely in outpatient settings. Lengths of stay are measured in days. Goals of admission have also changed greatly, from furthering development and building psychological “structure” (

2) to stabilizing symptoms, adjusting medication, and facilitating connections to outpatient care (

3).

These changes have been driven primarily by cost-containment pressures, but, in addition, some clinicians have feared that prolonged hospitalization could be deleterious for patients. Moreover, a large research literature has strongly suggested that brief inpatient or various forms of intensive outpatient treatment were equally or more effective for helping severely ill patients than traditional, longer-term inpatient programs (

4–

11).

Despite these findings, however, uncertainty remains about the soundness and safety of current practice. Intensive, experimental programs may adequately replace inpatient care, but few comparative data are available from naturalistic, clinical settings. Although briefer stays have not been shown to be associated with higher rates of readmission (

4,

5,

7–

13), many clinicians believe that patients are now discharged “sicker,” and the implications of this are uncertain (

14,

15). Finally, while hospitalization may erode autonomy or induce “regression” for some patients, theorists and planners of inpatient care have stressed its ego-enhancing aspects (

16). It is not known whether shorter admissions deprive patients of such therapeutic experiences or with what effects.

Between 1988 and 1996, a series of outcomes studies was carried out on the inpatient psychiatric service at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. During those years, lengths of stay and program philosophy were modified and a partial hospital program was added, changes that were similar to those made in many other inpatient programs. These changes provided an opportunity to study the outcomes of similar patients who were treated differently at several points of time and, therefore, the opportunity to assess effects of changes in care in a naturalistic, nonexperimental, clinical setting. Patients were assessed along multiple dimensions of functioning: symptom level, global functioning, work and social functioning, self-esteem, and use of ego defenses. Because outcome evaluations included 1-month follow-up interviews, the data also provided information on the effects of longer or shorter admissions on immediate posthospital functioning. Using these data, we examined whether patients improve to a greater or lesser extent during briefer stays, compared to longer ones.

METHOD

The studies were conducted on the Inpatient Psychiatry Service of the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital, part of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, in Lebanon, N.H. Patients were admitted during various blocks of time between 1988 and 1996 (cohort 1: 1988–1991, cohort 2: 1992–1993, cohort 3: 1995–1996), as part of an ongoing evaluation of the outcome of hospitalization and the effects of interventions designed to improve the treatment alliance between patients and staff. These interventions had no detectable effect on any outcome measures and so were not considered in further analyses. Patients in the first cohort (1988–1991) have been included in a previous report (

17); a subgroup of patients in that report are described here for comparison purposes.

All patients admitted to the hospital during the several periods in which the study was carried out were invited to participate in the study if they had a DSM-III-R or DSM-IV diagnosis of major depression. These diagnoses were formulated by at least two psychiatrists on the inpatient service. In addition, a sample of 12 records was independently reviewed by a board-certified psychiatrist who was not aware of the patients' clinical diagnoses or involved with their care. In each case, the diagnosis of depression was independently confirmed, although other, secondary diagnoses (including personality disorders, anxiety disorders, and adjustment disorders) were also made. Patients were included independently of whether they were psychotic or bipolar or had other comorbid axis I or axis II disorders. They were excluded if they had been admitted for ECT (although several subsequently received this treatment) or had a primary diagnosis of a substance use disorder, delirium, dementia, or psychiatric disorder secondary to another medical condition. Approximately 20% of patients who were eligible to enter the study refused to participate. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Two hundred six patients were enrolled and completed the initial evaluation.

Enrolled patients were interviewed by a member of the research team within 4 days of admission. Demographic data were collected, along with a brief summary of recent and past psychiatric and medical treatment. Patients were then administered the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (

18) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (

19). Videotaped interviews with nine patients were used to determine interrater reliabilities for the BPRS (intraclass correlation=0.67 for cohort 1 and 0.73 for cohorts 2 and 3) and for the Hamilton depression scale (intraclass correlation=0.73 for cohort 1 and 0.60 for cohorts 2 and 3). Patients were also asked to answer two sets of questions from the Strauss-Carpenter Prognostic Scale (

20) designed to measure aspects of work and social functioning: 1) they were asked how frequently they saw friends, and their answers were used to complete the “quantity of social relations” question of the Strauss-Carpenter scale; and 2) they were asked about their recent work histories (what jobs they had done, for how many hours, and for how long). This information was used to complete the “quantity of work functioning” item on the Strauss-Carpenter scale.

Patients were also asked to complete the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (

21) and the Bond Defense Inventory (

22), Andrews' modification (

23), a measure of ego defenses that yields three factor scores for mature, neurotic, and immature defenses. Since neurotic defenses do not change during a brief admission (

17), only scores for mature and immature factors are reported. On the basis of all interview data and review of the patient's medical record, the interviewer then completed the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (

24).

At discharge, all patients were again asked to complete the BPRS, Hamilton depression scale, Rosenberg scale, and Bond scale. One hundred sixty-one patients (78.2%) were reinterviewed. For cohorts 1 and 2, discharge functioning was evaluated at release from the hospital; for cohort 3, it was evaluated when patients were discharged from either the hospital (N=30) or the partial hospital (N=30). The partial hospital was used for patients who were still acutely ill, who lived nearby, and for whom it was safe to be home at night—either as a substitute for admission or to shorten one.

Of the original 206 subjects, attempts were made to reinterview 152 subjects 1 month after discharge. One hundred nineteen (78.3%) of these were reinterviewed. Information was obtained regarding work and social functioning during the first month at home, by using the Strauss-Carpenter “quantity of work” and “quantity of social relationships” questions. Patients were also asked about rehospitalization during this period and were administered the BPRS and Hamilton depression scale. With this information, the Global Assessment of Functioning scale was again completed.

Significance tests of differences between cohorts were computed for interval data by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher's least significant difference procedure when significant differences were found. (Since the variances in length of stay were significantly different among the three cohorts, the Kruskal-Wallace test and Mood's median test were used to compare the cohorts on length of stay.) Chi-square analysis was used for categorical data. Residual discharge and 1-month scores were calculated by using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with discharge or 1-month score as the dependent variable, admission variable as the covariate, and cohort as the grouping variable.

RESULTS

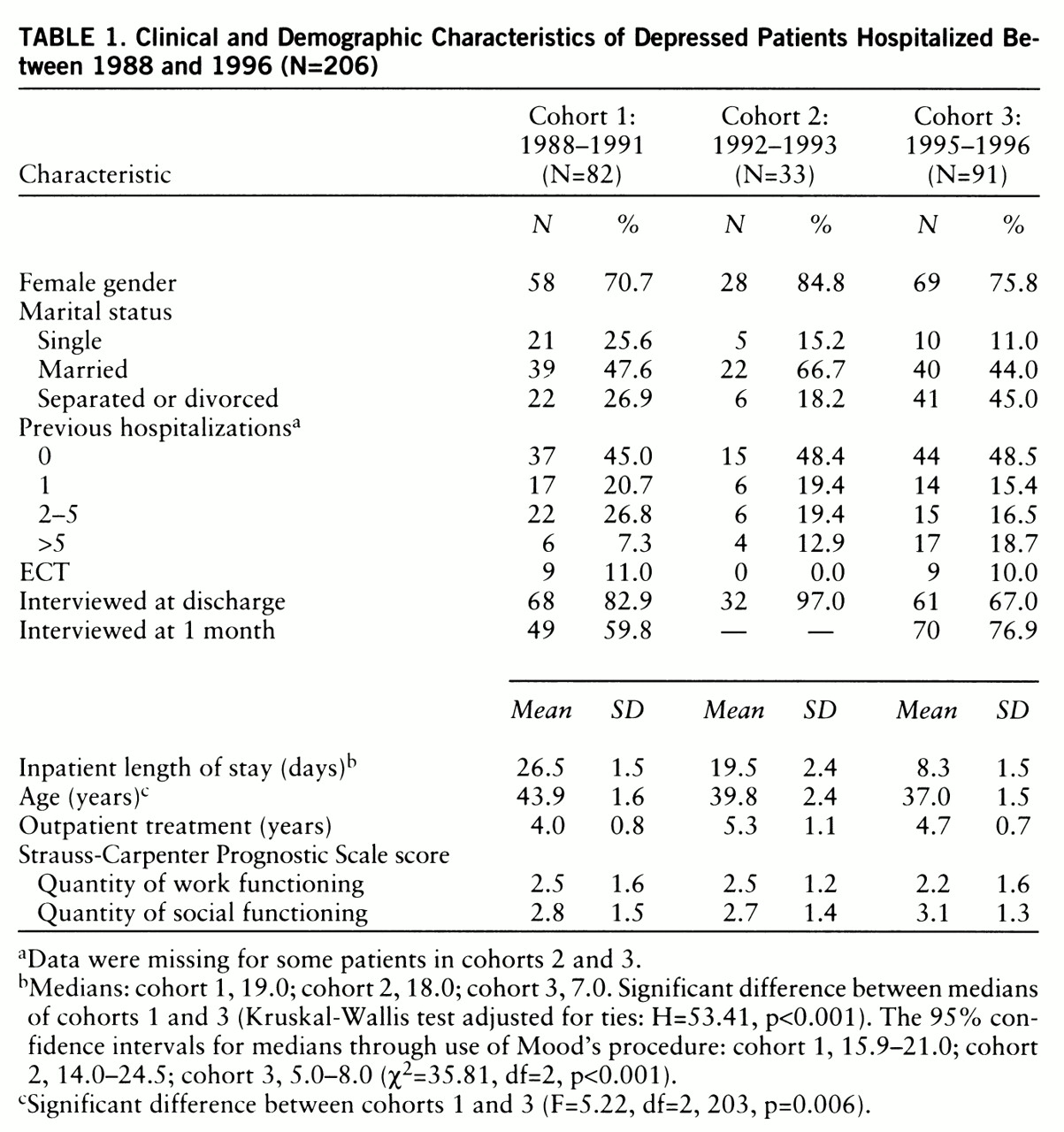

= The three cohorts of patients were compared on a number of clinical and demographic variables (

table 1). Cohort 3, the most recent, was significantly younger than cohort 1; correction was, therefore, made for age in subsequent comparative analyses. No differences among the cohorts were found in any other background variable.

Length of stay declined significantly between each pair of successive cohorts. Within cohort 3, there was a shorter length of stay for patients treated in the partial hospital program (mean=6.7 days, SD=1.6) than for those not so treated (mean=9.6 days, SD=1.3), but this difference was not statistically significant (t=1.39, df=79, p=0.17).

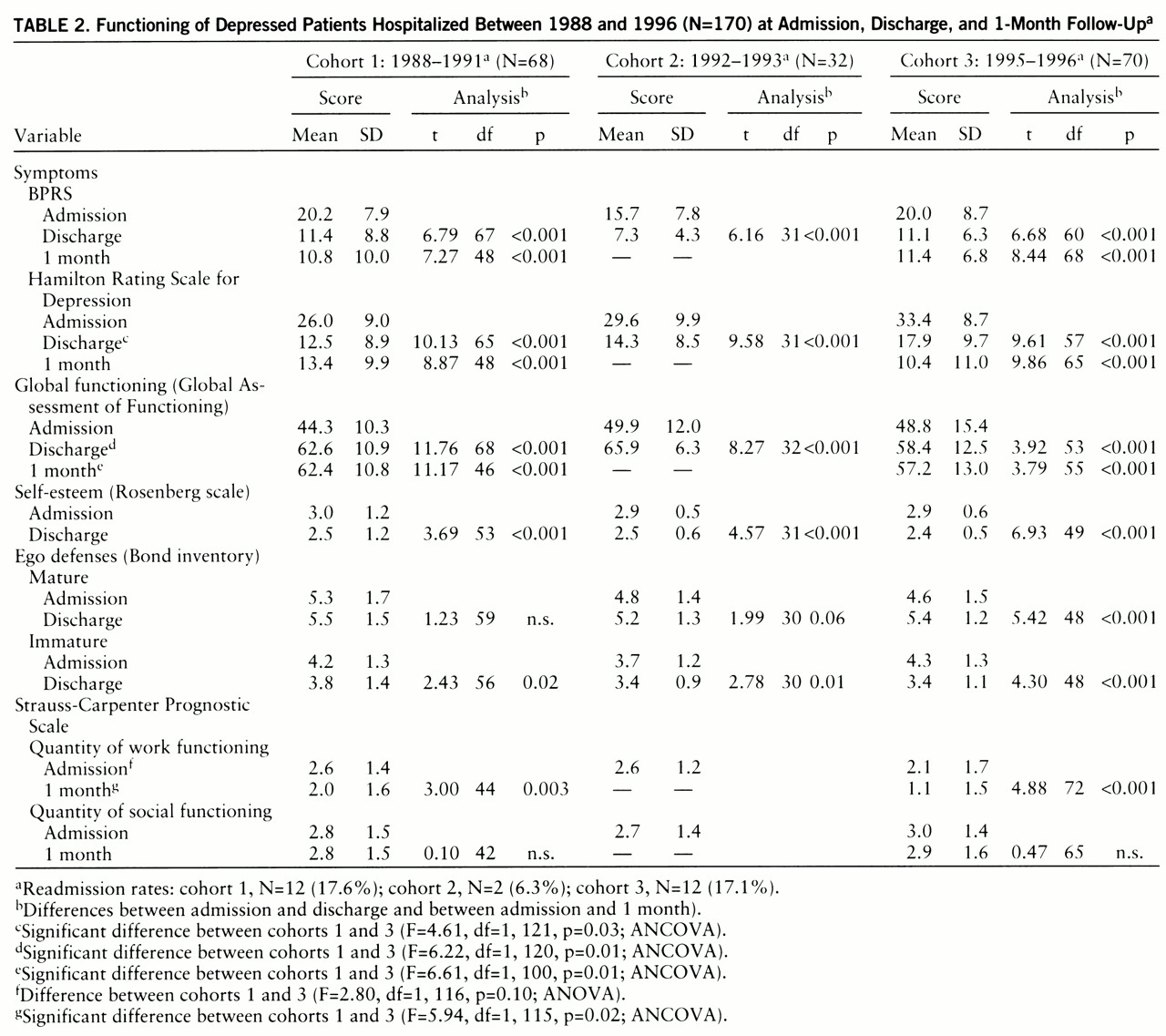

Despite these reductions in hospital stay, all areas of functioning improved for all three cohorts, and, in most cases, no differences in residual discharge scores could be found (

table 2). Thus, BPRS scores and ratings of self-esteem and of ego defenses were indistinguishable at discharge. So, too, were rates of rehospitalization within the first month. Within cohort 3, these outcomes were also indistinguishable in comparisons of patients treated entirely or in part in the partial hospital program and patients whose episode of care was provided solely in the hospital.

Some significant differences among the cohorts were observed, however. At discharge, patients in cohort 3 had significantly higher residual Hamilton depression scale and lower Global Assessment of Functioning scale scores than cohort 1. Although the difference in Hamilton depression scores failed to remain significant 1 month after discharge, that for Global Assessment of Functioning scores continued to be significant. Patients in cohort 3 showed significantly lower levels of work functioning in the month after discharge than patients in cohort 1, in comparing statistically for preadmission level of work functioning. These differences in Hamilton depression scale score, Global Assessment of Functioning scale score, and work functioning were observed both for patients treated in the partial hospital program and for those who were not so treated.

DISCUSSION

Psychiatric hospitalization has been a controversial institution, seen both as a place of asylum (

25) and one of abuse. Thus, it is not surprising that reductions in the time patients spend in hospitals should also meet with mixed responses. If prolonged hospitalizations have tended to undermine patients' autonomy and self-esteem, briefer admissions may preserve and strengthen them. Yet if admissions have provided valuable “living-learning” experiences (

2,

15) or protection from stress, short stays may deprive patients of therapeutic opportunities or release them prematurely.

Many experimental studies have demonstrated that intensive outpatient programs can successfully substitute for hospitalization, with equal or better outcomes (

4–

11). However, it is another matter whether actual clinical practice—where short stays are now mandated, often without clear clinical justification, and where alternative programs may be inadequate—can achieve comparably good results.

The current study offers some information on this question for patients with major depression, and its results are mixed. There appears to be a rapid improvement in several key areas of functioning—marked by BPRS scores, as well as measures of self-concept and ego functioning. Even when hospital stays are drastically shorter, these improvements occur. By contrast, as clinical experience suggests, depressed patients are now discharged more depressed than they previously were, and with lower scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale. One month after discharge, although readmission rates were equal, global and work functioning remained lower among the short-stay group.

This pattern of findings may be explained by the existence of several components within the acute recovery process. Frank and Frank have hypothesized that a process of “de-regression” can occur early in the course of psychotherapy, when patients show improved cognition, heightened self-esteem, and more “adaptive” ego functioning (

26,

27). Akkerman et al. (

28) have shown a similar improvement in ego functioning for a group of inpatients and outpatients treated in psychotherapy. The current data also support the existence of such a process during the hospitalization of depressed patients. Such de-regression during hospitalization may help patients to remain out of the hospital by improving their capacities to tolerate and cope with stress and symptoms.

Keeping patients in the hospital for weeks or months, rather than days, seems neither to erode nor to strengthen self-esteem or ego functioning in depressed individuals. The lack of a “dose-response” effect suggests that the improvement that does occur in these areas during admission (

17) is a return to baseline functioning rather than a process of learning or development. While some types of learning may occur, they were not measured by the variables we examined. A particularly important question in this regard is whether hospitalization provides patients with appropriate experiences and with enough information to encourage and facilitate their remaining in treatment after discharge. This question was not addressed by the current study.

A second component of the recovery process, for depressed individuals at least, seems to involves depressive symptoms themselves. These take longer to resolve than the types of improvements seen in de-regression. Patients discharged from short-stay admissions leave with relatively high levels of depressive symptoms that may continue to interfere with work and global functioning after they are released. Employers, family members, clinicians, and patients themselves may need to appreciate this limitation.

The finding that within cohort 3, participation in a partial hospital program had no effect on outcome was surprising. Although patients in the partial hospital program spent fewer days in the hospital, their overall time in intensive treatment tended to be significantly longer than that for patients treated only on the inpatient service—usually 2 to 3 weeks in all. A differential improvement in score on the Hamilton depression scale or Global Assessment of Functioning scale might have been expected during that time. The use of ECT, limited primarily to inpatients, may have attenuated such a difference. In addition, patients referred to the partial program may have been those whose recovery was slowed and who needed additional support and treatment. The small number of subjects in the partial hospital and non-partial hospital groups may have also reduced the likelihood of finding a difference between them.

In summary, these findings suggest a somewhat less sanguine appraisal of shortened hospital stays than do controlled, experimental studies. While it is true that significant improvement can occur during such brief admissions, patients are now more depressed and more globally impaired when they leave the hospital. This degree of symptoms and impairment may adversely affect their ability to function in the first weeks after discharge.