Compulsive buying is characterized by inappropriate shopping and spending behavior that leads to impairment manifested through personal distress; social, marital, or occupational dysfunction; or financial or legal problems (

1). Compulsive buying is classified in DSM-IV as an impulse control disorder not otherwise specified; it is unclear whether compulsive buying is related to mood disorders, substance use disorders, or impulse control disorders or whether it falls within an obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) spectrum. Regardless of how it is classified, the disorder has an estimated prevalence of between 2% and 8% and is associated with substantial axis I psychiatric comorbidity, particularly mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders (

1–

5). Schlosser et al. (

3) have reported a high frequency of axis II disorders in compulsive buyers.

Apart from consumer behavior research (

4,

5), most work with compulsive buyers has focused on illness description and assessment of symptoms and psychiatric comorbidity (

6,

7). Treatment studies have only recently begun, and family history data are scanty. McElroy and colleagues (

8) reported family history data on 18 compulsive buyers; 17 had one or more first-degree relatives with a mood disorder, 11 with alcohol or substance abuse, and three with an anxiety disorder; three had relatives who were compulsive buyers. As these data suggest, compulsive buying itself may run in families. We have seen, for example, compulsive buyers who report that the disorder affects three generations, usually following the maternal lineage.

We now extend the literature on psychiatric comorbidity and family history by presenting the findings in a group of 33 compulsive buyers who volunteered for treatment trials. Data were systematically collected and are contrasted with findings from a comparison group.

METHOD

Compulsive buyers were recruited by word of mouth and through newspaper advertisements reading: “We are inviting persons 18 and older who have a compulsive buying problem to participate in a treatment study. Compulsive buying creates a strong urge to buy which cannot be controlled.” Thirty-three persons were enrolled for participation in medication treatment trials between February 1994 and September 1997. Subjects were eligible if they were at least 18 years old, met the criteria of McElroy et al. (

1) for compulsive buying, had been compulsively buying and spending for over 1 year, and scored two standard deviations or more above the mean on the Compulsive Buying Scale (

9). We required that compulsive buying be the predominant problem and excluded persons with a diagnosis of lifetime bipolar disorder (since bipolar disorder may lead to inappropriate buying and spending) and those in whom compulsive buying was felt to be secondary to OCD. Other reasons for exclusion were current (but not lifetime) major depression, current substance use (past 6 months), a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and the presence of a severe personality disorder or suicidal behavior, since these conditions could have interfered with participation in the clinical trial.

Twenty-two comparison subjects were recruited through a hospital newsletter in the course of a family study of OCD. The advertisement read as follows: “Persons with at least one child between ages 7 and 18 are invited to participate in a health care survey.” Subjects were screened with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (

10). They could not be psychotic, have current substance abuse (past 6 months), be suicidal, have a primary neurologic condition, or be mentally retarded, since these conditions could have interfered with data collection. Lifetime OCD was also a reason for exclusion, although no subjects were actually excluded for this reason. Buying behavior was not assessed.

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, in accordance with procedures approved by our institutional review board. After giving informed consent, both compulsive buyers and comparison subjects were evaluated by a trained rater (J.G.) who was not blind to proband group assignment (

11). Social and demographic data were collected on all probands. Subjects were given the SCID in order to assess the presence of axis I disorders (

10). The Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria were used to collect information about psychiatric disorders in first-degree relatives.

We used a two-tailed Fisher's exact test for categorical comparisons, which provide exact probabilities, not approximations like the chi-square test. Continuous data were analyzed by using Student's t test. We did not correct for the number of comparisons for two reasons. First, all comparisons were preplanned. Second, the Bonferroni correction assumes that all tests are independent, not true of diagnostic comparisons for comorbidity or family history. In each case, the disorders are diagnosed with the same instrument, leading to several dependent comparisons. Thus, a Bonferroni correction would be overly strict.

Family history data were also tested with the nonparametric Mantel chi-square extension test with one degree of freedom; ranks were used for scores, since the family was treated as the unit of analysis (

12).

RESULTS

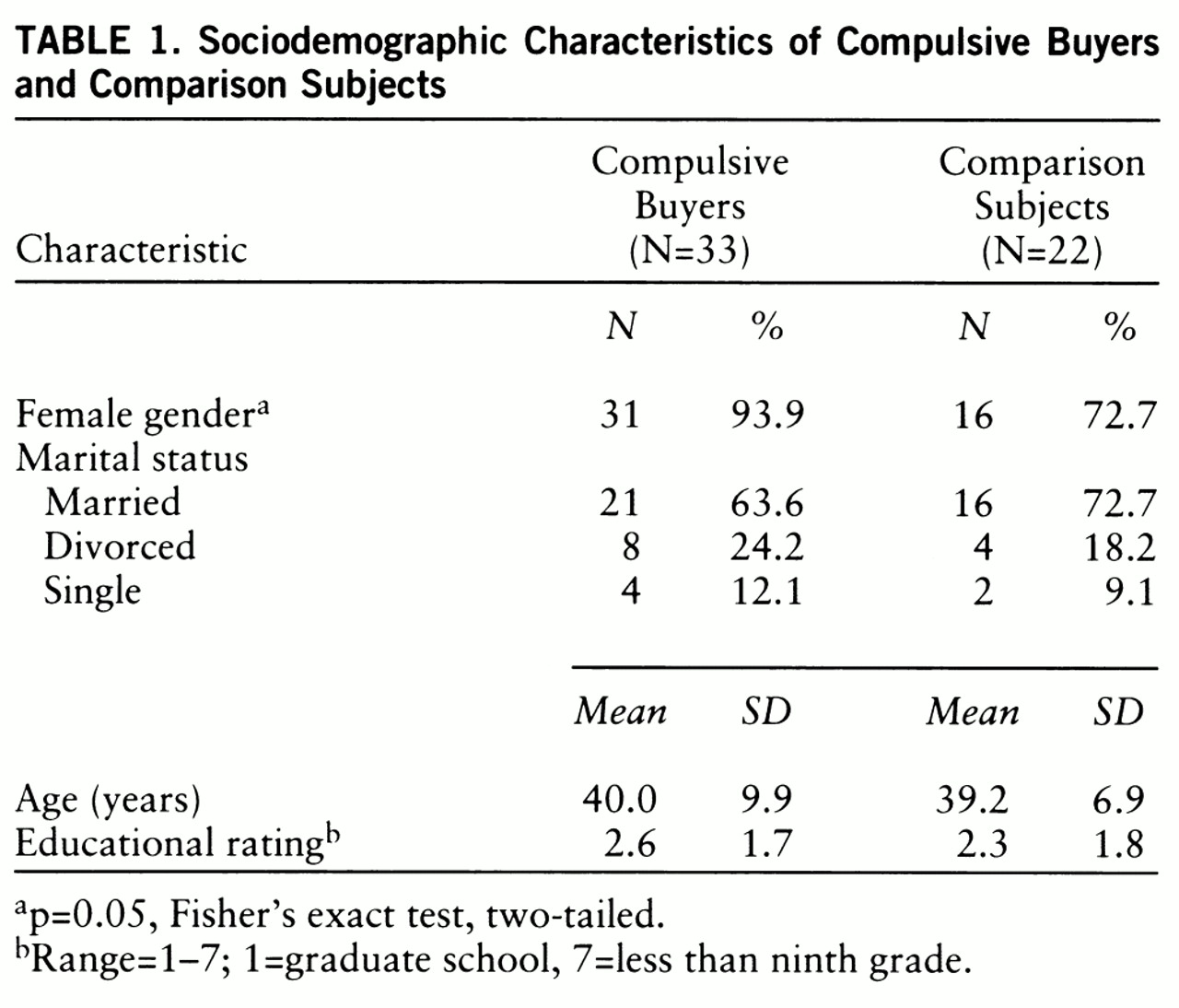

The sociodemographic profile of compulsive buyers and comparison subjects is presented in

table 1. The two groups differed in gender distribution but not in age, marital status, or educational achievement.

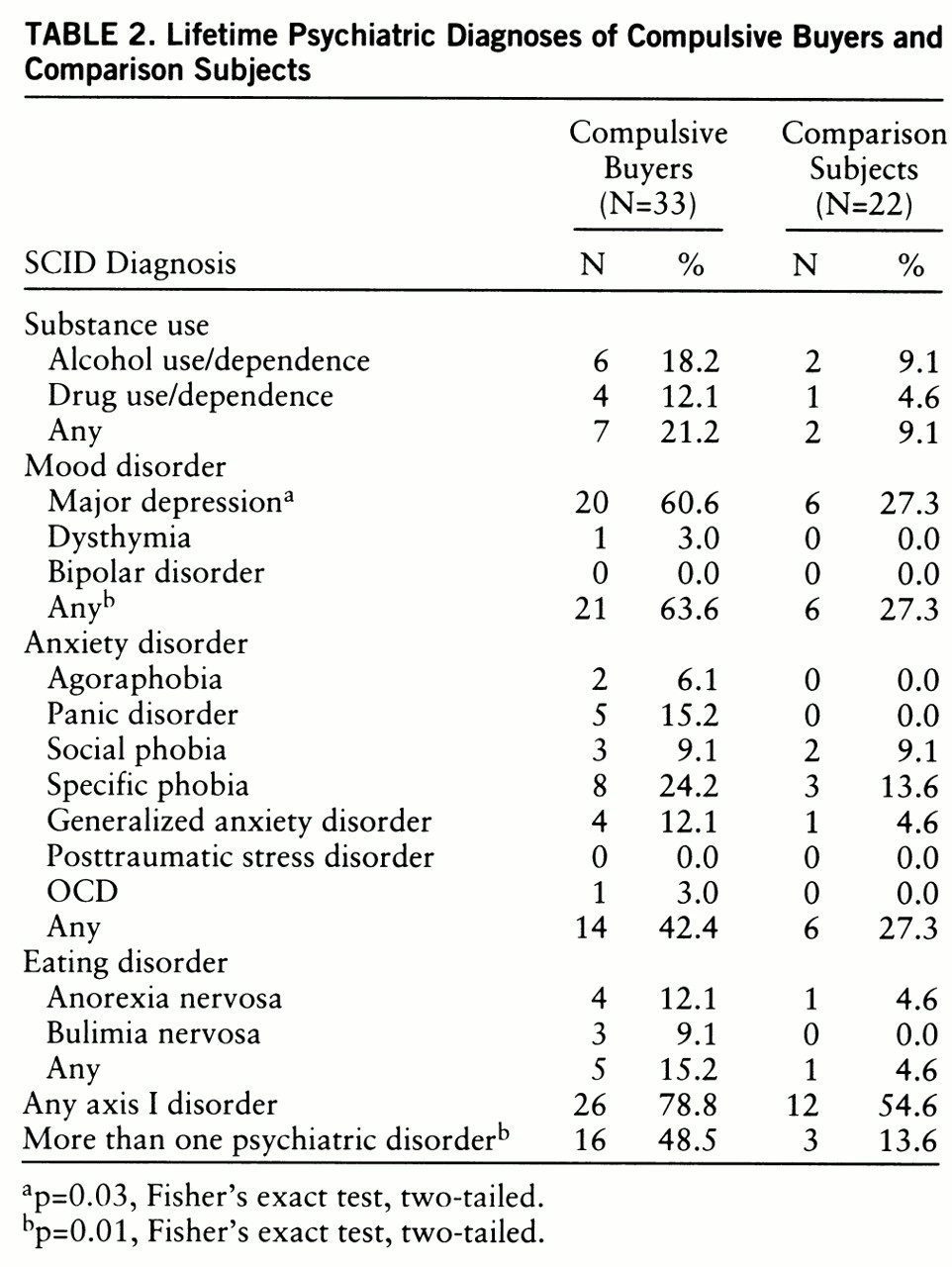

Table 2 presents data on psychiatric comorbidity assessed with the SCID. Compulsive buyers were significantly more likely than comparison subjects to have major depression, any mood disorder, and more than one psychiatric disorder.

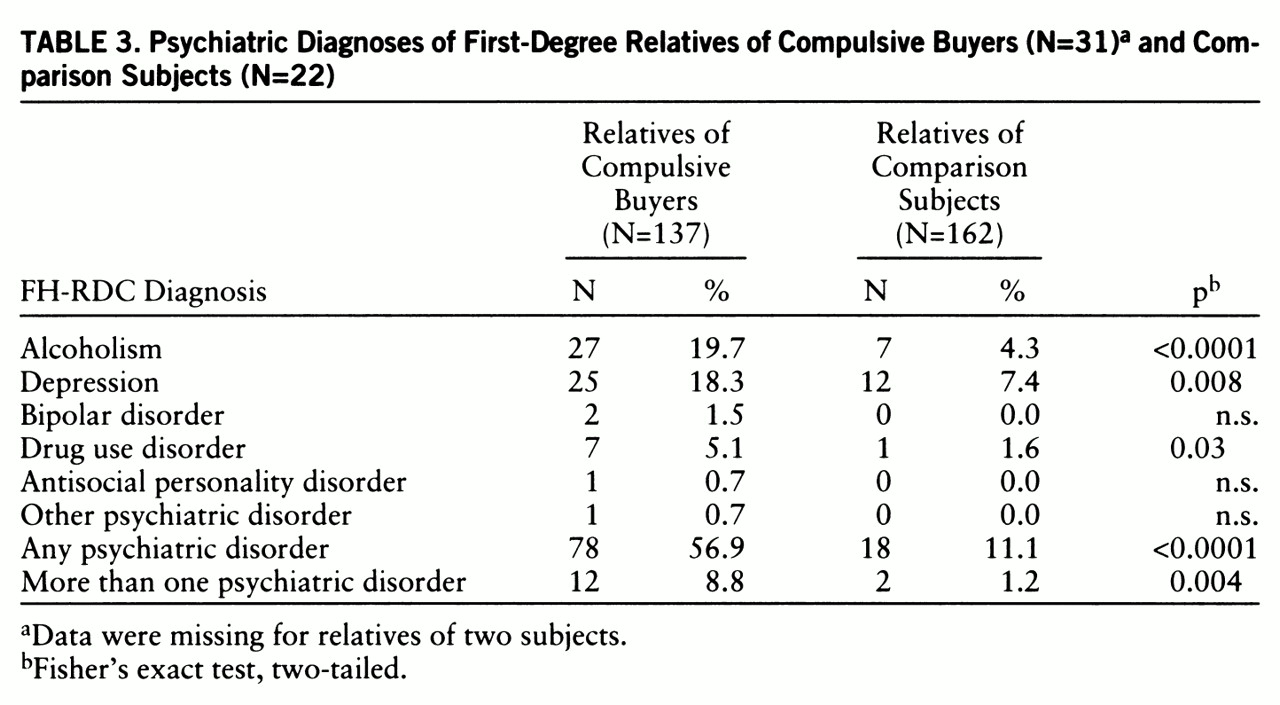

The frequency of psychiatric disorders among first-degree relatives of compulsive buyers and comparison subjects is presented in

table 3. Significantly more relatives of compulsive buyers had depression, alcoholism, or drug abuse and were also more likely to have any, or more than one, psychiatric disorder. Compulsive buying was identified in 13 (9.5%) of the first-degree relatives of compulsive buyers but was not assessed in the comparison relatives. For the purpose of this study, our definition of compulsive buying in relatives required that they be described as compulsive buyers or spenders and that the behavior had led to distress and interpersonal, legal, or financial difficulties.

The data in

table 3 were also analyzed by using the family as the unit of interest. Relatives of compulsive buyers were more likely than comparison relatives to have alcoholism (χ

2=4.19, df=1, p=0.04) and any psychiatric disorder (χ

2=5.39, df=1, p=0.02).

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that persons reporting compulsive buying behavior who volunteered for medication trials are more likely than comparison subjects to suffer lifetime mood disorders (especially major depression) and to suffer more psychiatric disorders in general. This finding is partially consistent with reports in which comorbidity was assessed (

1–

3). A review of three reports confirmed high rates of mood, anxiety, substance use, eating, and impulse control disorders (

6). Although only one of the three reports had a comparison group (

2), the figures cited for axis I disorders were all higher than those of epidemiologic samples (

13,

14). In the report by Christenson et al. (

2), compulsive buyers were found to have more mood, anxiety, eating, impulse control, and substance use disorders than “normal” buyers. In other studies, compulsive buyers have scored high on dimensional measures of depression, anxiety, and obsessionality and low on measures of self-esteem (

4,

5).

The study results also indicate that first-degree relatives of probands with compulsive buying are significantly more likely than relatives of comparison subjects to have a mental disorder, particularly depression, alcoholism, and drug use disorders. There was also a higher rate of general psychopathology among the relatives of compulsive buyers. While the family dynamics of compulsive buyers have not been systematically studied, several reports suggest that they are chaotic and disturbed, findings that could be partially explained by these data (

15,

16). Although no investigators have systematically addressed the issue of family psychiatric history in compulsive buying, McElroy and colleagues (

8) reported uncontrolled findings suggesting higher rates of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Our results also suggest that compulsive buying itself may run in families, since 9.5% of compulsive buyers' relatives had the disorder. No comparison data are available, but the reported prevalence is less (

9).

The study provides another confirmation that persons reporting compulsive buying behavior suffer from an excess of mental disorders, as do their first-degree relatives. Given these results, it remains unclear whether compulsive buying is related to mood, anxiety, or impulse control disorders; however, the data argue against its inclusion in the OCD spectrum, since neither subjects nor their first-degree relatives suffered an excess of OCD.

The limitations of the study need to be addressed. First, the group was relatively small, and data collection was incomplete. A larger group size would have provided greater statistical power to help determine differences between study subjects and comparison subjects. The compulsive buyers were predominantly white women who presented for treatment trials, and they therefore may not be representative of compulsive buyers in general or of those who present in other clinical settings. Furthermore, subjects used for the comparison were not specifically matched with the characteristics of the compulsive buyers. Although a greater percentage of compulsive buyers were women, other group characteristics were similar. Among compulsive buyers, certain disorders (including OCD) were reason for exclusion. This suggests that rates of psychiatric comorbidity among compulsive buyers may actually be higher than what we reported. However, no compulsive buyers or comparison subjects were excluded because of the presence of OCD. Last, the results are based on family history data obtained from probands, a method less desirable than the direct interview of relatives because probands may not be familiar with or able to describe a relative's psychiatric symptoms.

Nonetheless, the data are helpful in furthering our understanding of a heretofore ignored group of individuals. Additional work is needed to confirm and extend these findings in other settings and with larger groups. In particular, more work is needed to help explain the relationship of compulsive buying to a family history of mood and substance use disorders.