He [a discharged inpatient] has left over 200 messages on my voice mail.

He has followed me home and threatened to kill me.

He has been stalking my children.

I have received multiple “Tarasoff warnings” in the last week.

Nothing I do makes him stop.

—Adapted from notes of hospital staff members

One of the concerns of mental health clinicians is that they may be the target of violence. According to APA's Task Force on Clinician Safety (

1), approximately 40% of psychiatrists, and an even higher percentage of psychiatric nurses, have been assaulted by patients. The most common contexts for such violence are settings such as inpatient units and psychiatric emergency rooms, where the most acutely ill individuals are generally treated.

Unfortunately, some patients continue to focus their aggressive behavior on hospital treatment staff even after discharge (

2). Although previous research with people in jails or prisons has identified attributes of stalkers or “obsessional followers” (

3,

4), no systematic research has been done on psychiatric inpatients who stalk, threaten, or harass hospital staff after discharge. To our knowledge, this study is the first to compare the characteristics of these patients to those of other patients treated in the same setting.

METHOD

The study was conducted on a university-based short-term psychiatric inpatient unit. As a security measure in this setting, patients who stalk, threaten, or harass staff members are described in an “on call” book, and they are also discussed in meetings of a hospital safety and security subcommittee. The types of behavior that are reportable include oral and written threats of harm, harassing telephone calls, unwanted approaches and following, and unspecified stalking behavior.

The study involved retrospective review of hospital records to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of 17 patients who had been identified over 6 years as having stalked, threatened, or harassed staff after discharge from the hospital. To place the attributes of these 17 patients in context, we compared them to typical inpatients in our hospital, using demographic and clinical information that had been collected on 326 other inpatients in an unrelated previous study (

5).

Violent behavior that occurred before hospital admission was rated by using an adaptation (

6) of the coding system developed by Lagos et al. (

7), which classifies patients as having shown no violence, fear-inducing behavior (attacks on objects, threats to attack persons, or verbal attacks on persons), or physical attacks on persons. Violence during hospitalization was rated by nursing staff at the end of each 8-hour shift with the Overt Aggression Scale (

8), a widely used index of inpatient aggression with documented reliability and validity (

9). Ratings on the Overt Aggression Scale were summarized by classifying each patient as having shown no violence, fear-inducing behavior, or physical attacks on persons during hospitalization.

Differences between the 17 patients who stalked, threatened, or harassed staff after discharge and the comparison group were evaluated by using chi-square analyses (corrected for continuity where appropriate) for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Because of the constraints on statistical power associated with the small size of our study group and because this is the first study of this topic of which we are aware, nominal p values are presented to facilitate interpretation of the results and generation of hypotheses.

RESULTS

Of the 17 inpatients who stalked, threatened, or harassed hospital staff after discharge, two (12%) targeted attending psychiatrists, six (35%) targeted psychiatric residents, six (35%) targeted nurses, and three (18%) targeted unspecified staff members. One patient (6%) engaged in stalking behavior that was so disruptive to staff that criminal charges under an antistalking statute were filed against the patient. Four of the patients (24%) approached staff in a threatening or harassing manner, 10 (59%) made oral or written threats of harm or unwanted telephone calls without physically approaching staff, and two (12%) engaged in unspecified stalking behavior. None of the patients physically attacked staff after discharge, and the duration of the behavior was generally only a few weeks.

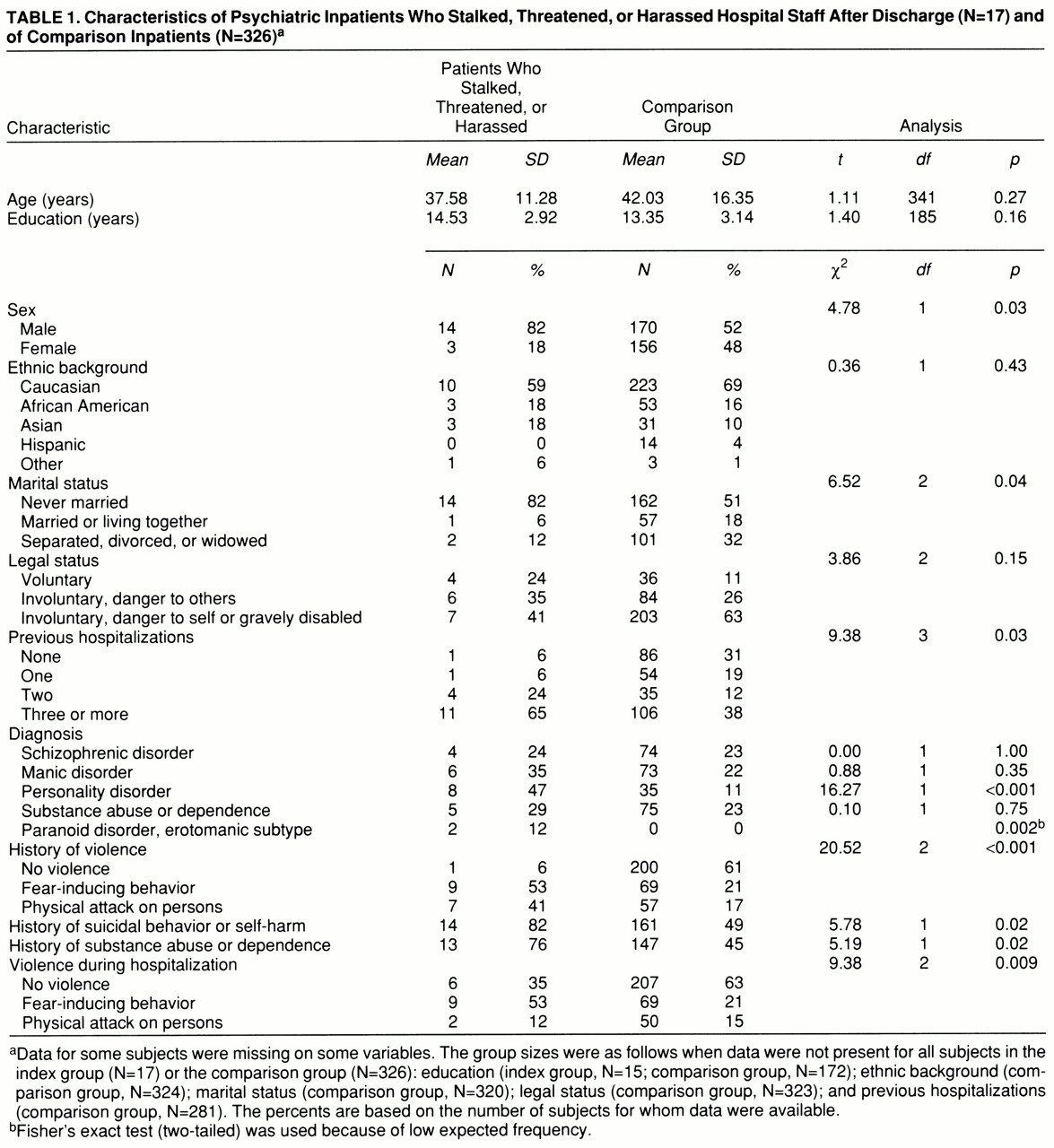

As shown in

table 1, the patients who stalked, threatened, or harassed staff after discharge were significantly more likely than the comparison patients to have a diagnosis of a personality disorder or paranoid disorder, erotomanic subtype, and they were more likely to have a preadmission history of fear-inducing or physically assaultive behavior (94% and 38%, respectively). The data suggest that these patients were more likely than the comparison patients to be male, to have never been married, and to have histories of multiple hospitalizations (88% and 50%, respectively), suicidal or self-injurious behavior, substance abuse or dependence, and fear-inducing or physically assaultive behavior during hospitalization (65% and 36%, respectively).

The study and comparison groups did not differ significantly in terms of age, education, ethnic background, or legal status. The patients in both groups tended to be Caucasian and to have at least a high school education, and the two groups combined had a mean age of 41.81 years (SD=16.15). Most patients in both groups had been involuntarily admitted to the hospital.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically compare the characteristics of psychiatric inpatients who stalk, threaten, or harass hospital staff after discharge with features of other patients treated in the same setting. Our study group differed from previous groups of stalkers and “obsessional followers” in two important ways. First, our subjects were civilly committed psychiatric inpatients, not incarcerated individuals facing criminal charges. Second, all of our subjects targeted hospital staff, as opposed to strangers, acquaintances, domestic partners, or celebrities. Despite these differences, our findings are similar to data obtained in forensic settings (

10). As is the case for forensic subjects, the former inpatients in our study who stalked, threatened, or harassed staff tended to be more likely than comparison patients to be male and to have had an extensive history of prior psychiatric treatment. In addition, there was a striking overrepresentation of patients with characterological features in our study group. Traditionally described as having “attachment pathology” or “distorted object relations,” these individuals have serious, long-standing interpersonal difficulties associated with the way they perceive, relate to, and think about the environment and themselves (DSM-IV). Our group of stalking, threatening, and harassing patients also contained proportionately more patients with paranoid disorder, erotomanic subtype (two of 17) than the comparison group (none of 326). This result is consistent with descriptions of forensic subjects, although replication with larger groups is needed to further evaluate this preliminary finding.

The small number of patients who stalked, threatened, or harassed staff after hospital discharge limits the sensitivity of our study to detect differences between these patients and the comparison group. Nevertheless, the patterns that were apparent are consistent with what would be expected on the basis of prior research and suggest fruitful avenues for further investigation of this topic. The association that was found between a history of aggressive behavior and stalking, threatening, or harassing staff is consistent with prior research showing that the best predictor of future aggression is a history of past aggression (

6,

11). Similarly, the association between substance abuse or dependence and this type of behavior is consistent with research demonstrating that substance-related disorders are linked to aggressive behavior by mentally ill persons in the community (

12,

13).

In this study we relied on archival sources to identify former inpatients who stalked, threatened, or harassed hospital staff after discharge. It is possible that other patients engaged in this type of behavior that staff did not formally report, as denial and minimization are common reactions to being the target of patients' aggressive behavior. However, it is reasonable to assume that the former inpatients perceived by staff as the greatest threat were identified in the archival sources.

Although the total number of discharged patients who return to stalk, threaten, or harass hospital staff is small, the problem occurs with sufficient frequency to warrant systematic attention in formulating clinical management strategies and hospital policies. It is noteworthy that none of the discharged patients in our study group physically harmed hospital staff, and in most cases the problem behavior was limited to the period shortly after discharge. Nevertheless, their stalking, threatening, and harassing behavior had a disruptive impact on the functioning of the hospital and the perceived safety of the staff. Staff became more vigilant, and some took precautions that disrupted their lifestyles and work habits, such as changing telephone numbers, work schedules, and place of residence.

In summary, the present study identifies variables that are likely to be useful in formulating systematic responses to patients who stalk, threaten, and harass staff after hospital discharge. Future research is needed to empirically demonstrate the efficacy of specific management strategies for this issue.