The present study involved 347 patients with major affective disorders, psychoses (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophreniform psychosis), or personality disorders. Our goal was to determine the generalizability and relative importance of risk factors for suicidal acts across diagnostic boundaries. Structured clinical interviews generated axis I and axis II diagnoses, and we measured key personality characteristics such as aggression and impulsivity, recent life events, and a variety of clinical and demographic variables. The goal of this study was to develop a hypothetical, explanatory, and predictive model of suicidal behavior that can subsequently be tested in a prospective study.

RESULTS

Patients who had attempted suicide recently or in the past did not significantly differ from nonattempters in age (mean=32.0, SD=9.5, versus mean=32.7, SD=11.1) (t=–0.65, df=321.1, p=0.52), percentage of males (51% versus 52%), percentage married (14% versus 17%) (χ2=0.40, df=1, p=0.53), percentage Caucasian (66% versus 71%) (χ2=0.71, df=1, p=0.40), height (mean=67.3 cm, SD=4.2, versus mean=67.2 cm, SD=4.1), or number of children (mean=1.2, SD=1.5, versus mean=1.4, SD=1.7) (t=–0.67, df=264, p=0.50). Attempters had significantly fewer years of education (mean=12.7, SD=2.6, versus mean=14.0, SD=3.0) (t=–3.93, df=317, p=0.0001). However, this difference was not substantial enough to be clinically significant. The median personal income in the previous year was low in both groups, but for attempters it was 25% lower than for nonattempters ($6,000 versus $8,000) (χ2=8.03, df=1, p=0.005). Fewer attempters were Catholic (27% versus 41%) (χ2=6.6, df=1, p=0.01).

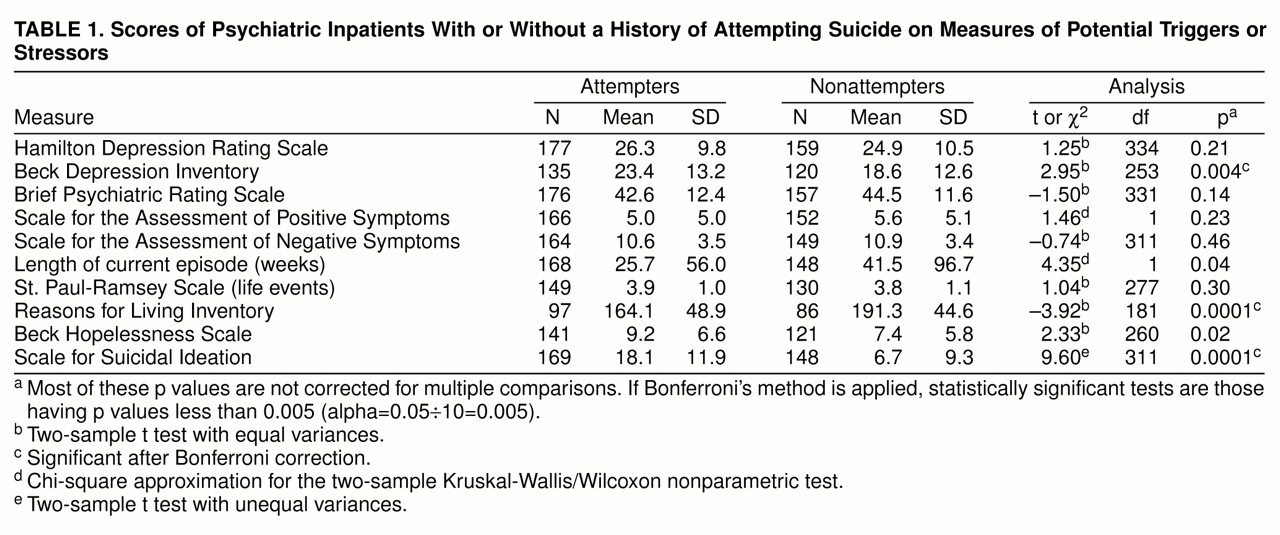

Table 1 shows that attempters and nonattempters did not differ significantly on objective severity measures of acute psychopathology, such as major depression (Hamilton depression scale), psychosis (SAPS and SANS), and general psychopathology (BPRS), In contrast, subjective ratings of depression (Beck Depression Inventory), hopelessness (Beck Hopelessness Scale), and severity of suicidal ideation were all significantly greater in suicide attempters. Duration of current episode, another measure of severity of depression, was longer in nonattempters, indicating that attempters had shorter exposure to depression during the current episode. Attempters had more lifetime episodes of major depression or psychosis (median=3 in attempters versus 2 in nonattempters) (χ

2=4.18, df=1, p=0.04) and a younger age at onset of illness (median=23 years in attempters versus 27 years in nonattempters) (χ

2=13.8, df=1, p=0.0002). Although the level of stress associated with life events (St. Paul-Ramsey Scale) did not appear to differ significantly between the two groups, the suicide attempters reported significantly fewer reasons for living (

table 1).

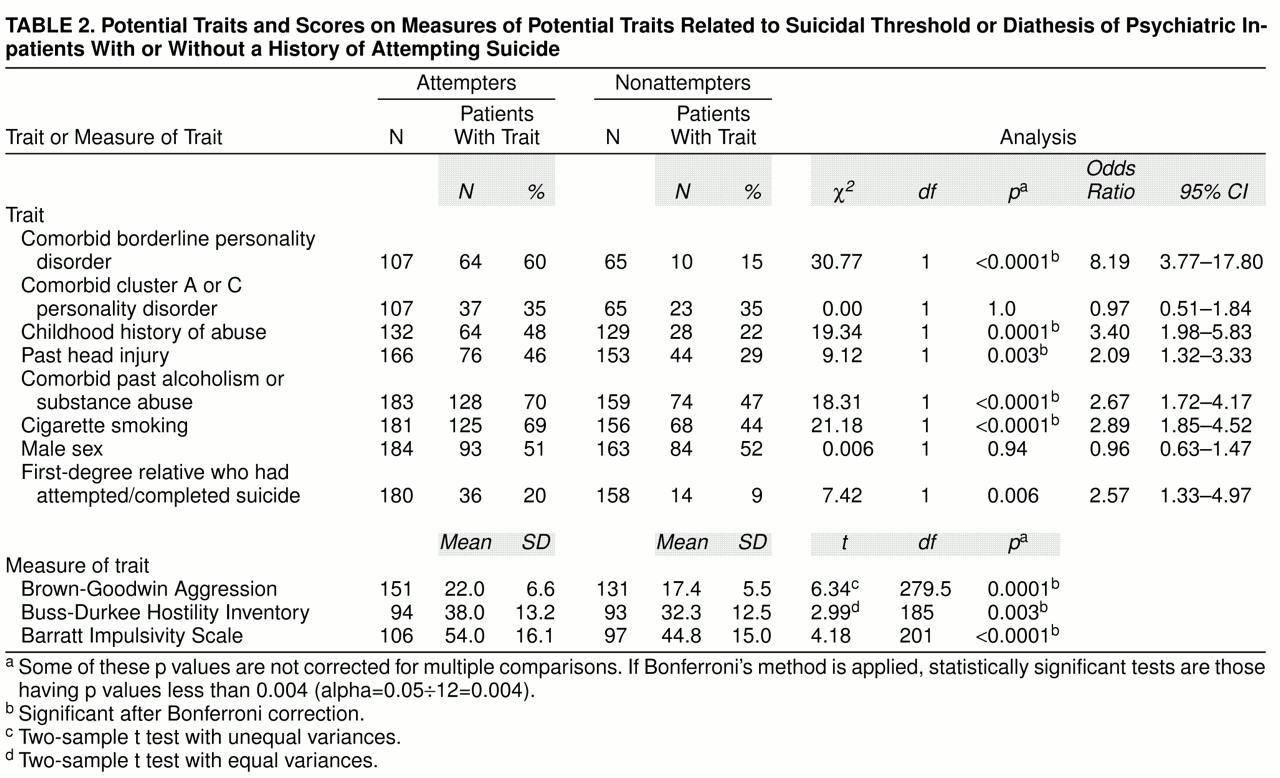

Table 2 addresses traits or stable characteristics and chronic conditions that have been implicated in suicidal behavior. In contrast to the findings in

table 1, many differences were found between attempters and nonattempters. Attempters had significantly higher scores for lifetime aggression and impulsivity as well as higher rates of comorbid cluster B personality disorders, comorbid past alcoholism or substance abuse or dependence, smoking, head injury, and a family history of a first-degree relative who had attempted or completed suicide. Most of these differences were highly significant, even when Bonferroni’s method for multiple comparisons was applied (

table 2).

Detailed results of the factor analyses of the state-dependent and trait-dependent psychopathology rating scale scores, including scoring coefficients that indicate how the factor scores were computed from the rating scales, are available on request. Two state factors (total variance explained: 75%) and one trait factor (total variance explained: 64%) were generated. We called the state factors the psychosis factor (derived from BPRS, SAPS, and SANS) and the depression factor (derived from the Hamilton depression scale, Beck Depression Inventory, and Beck Hopelessness Scale) because of correlations with state-dependent measures of these components of psychopathology. We called the trait factor the aggression/impulsivity factor (derived from Brown-Goodwin, Buss-Durkee, and Barratt scales).

A logistic regression model in which suicide attempter status was the dependent variable and the three factors were the independent variables indicated that only the aggression/impulsivity factor was strongly associated with lifetime suicide attempt (odds ratio=3.30, 95% confidence interval=1.99–5.47, p=0.0001). The psychosis factor (odds ratio=1.17, 95% confidence interval=0.78–1.75, p=0.45) and the depression factor (odds ratio=0.98, 95% confidence interval=0.66–1.46, p=0.94) were not significant predictors.

The addition of other independent variables, such as comorbid borderline personality disorder, past head injury, abuse in childhood, and a positive family history for suicidal behavior, did not alter the finding that the two state factors did not appear to predict attempter status. The addition of the score for severity of suicidal ideation to the logistic regression with the three factors did not alter the finding that the aggression/impulsivity factor is an important predictor of attempter status (odds ratio=3.10, 95% confidence interval=1.73–5.57, p=0.0001 for the factor versus odds ratio=1.10, 95% confidence interval=1.05–1.16, p=0.0001 for suicidal ideation).

Because about 41% of attempters had attempted suicide within 30 days of hospitalization, we also ran the logistic regression model including only these recent attempters to address the possibility that, since the psychosis and depression factors reflected current acute state, they were more likely to be associated with suicidal behavior that occurred more recently. The results were unchanged. The aggression/impulsivity factor was a significant predictor of recent attempter status. Suicidal ideation is also an important predictor (according to the logistic regression described earlier) and is correlated with the aggression/impulsivity factor (r=0.28, N=137, p=0.001).

Missing data did not explain the findings of the logistic regression model with the three factors (complete data were required for all items of all nine rating scales for each subject included). We compared subjects included in the multivariate analysis (N=126) with those who were dropped (N=221). No significant differences were found in any demographic or clinical variable except for slightly higher personal income, higher percentage Caucasian (78% versus 62%), and more lethal lifetime suicide attempts (3.8 versus 3.1) (t=2.44, df=181, p=0.02) in the group included in the logistic regression models with the three factors.

DISCUSSION

A trait factor, aggression/impulsivity, assessing lifetime externally directed aggression and impulsivity, was highly significant in distinguishing past suicide attempters from nonattempters. Individuals with a past history of attempting suicide exhibited greater lifetime aggression and impulsivity than nonattempters with the same psychiatric illness. Hostility in association with major depression and other psychiatric conditions has been reported to be linked to suicidal behavior (

28,

79) but not defined on the basis of lifetime behavior or stable trait-like features. A more pronounced impulsive-aggressive trait characterizes individuals at risk for suicide attempts regardless of psychiatric diagnosis. Most previous studies could not specifically address this point because they either examined one diagnostic group (

8,

11,

20–25,

27,

28,

55– 57,

80,

81), had too few cases to separate diagnostic groups (

79), or did not specify diagnoses (

15,

16,

54).

Externally directed aggression, suicidal acts, and other manifestations of impulsivity are all highly related (

79,

82,

83). Our scales cannot separate impulsivity from its manifestations, such as aggression or borderline personality disorder. For example, the aggression/impulsivity factor comprises scores from the aggression and impulsivity scales, features also found in borderline personality disorder. A diagnosis of borderline personality disorder and the aggression/impulsivity factor were both robust predictors of attempter status but were strongly interdependent. Patients with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder scored much higher on the aggression/impulsivity factor than those without borderline personality disorder (0.54 versus –0.16) (t=3.09, df=83, p=0.003). The component of borderline personality disorder that best correlated with suicidal behavior was impulsivity, highlighting the importance of impulsivity in determining risk of suicidal acts (

64). Greater impulsivity or impaired decision making may underlie a generalized propensity to suicidal and aggressive acts. Impulsivity is measurable by neuropsychological tests that ultimately may prove to be more sensitive than a clinical history.

Clinicians intuitively rely on objective measures of severity of psychiatric illness as a guide to the risk for suicidal acts. Our findings and those of others indicate that objective severity of illness does not distinguish patients with a history of suicide attempts (

47, 83– 85). Given the cumulative evidence that a history of suicide attempt elevates the risk for future suicidal acts (

13), objective severity of illness is also unlikely to predict future suicide attempts. This observation emphasizes the importance of the diathesis or trait-like predisposition, relative to severity of the illness, in predicting suicidal acts.

Patients with recurrent major depression or schizophrenia, who have a history of suicide attempt(s), make the attempt(s) relatively early in the course of illness (

10,

83). In our study, the attempters had made an average of 2.5 lifetime suicide attempts, evidence that suicide attempters have a predisposition to suicidal acts. The predisposition to suicidal acts appears to be part of a more fundamental predisposition to both externally and self-directed aggression.

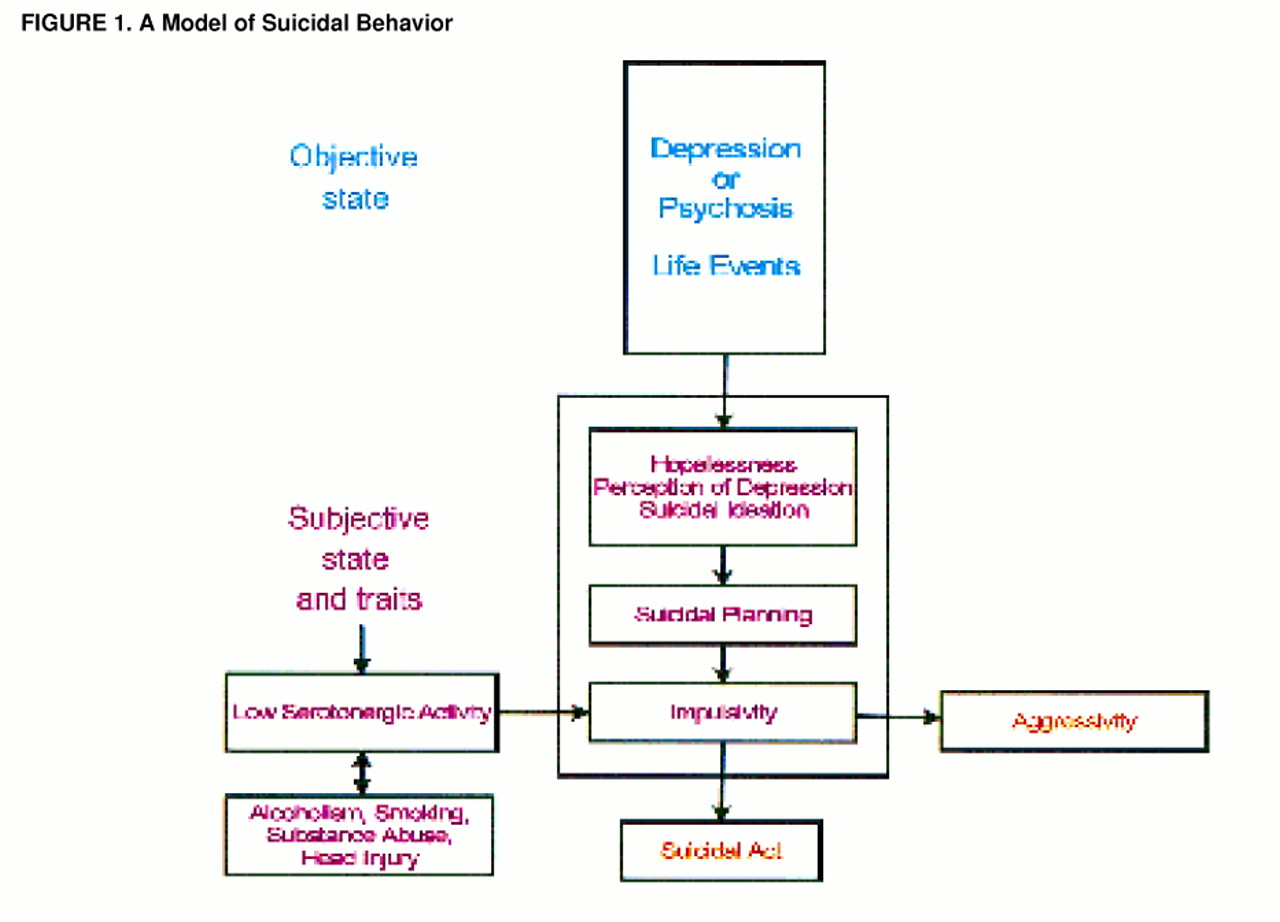

The model shown in

figure 1 summarizes our results. Subjective depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation were greater in suicide attempters than in nonattempters, despite comparable rates of objective severity for depression or psychosis. Conversely, suicide attempters scored lower on the Reasons for Living Inventory—a scale that has been considered to measure the protective effect of having more reasons for living (

75). The Reasons for Living Inventory score correlated negatively with hopelessness, providing further support for the notion that the Reasons for Living Inventory is an index of deterrents to suicide. There was no significant difference in life events between attempters and nonattempters; therefore, life events do not appear to explain the perception of fewer reasons for living. The more pronounced adverse response of suicide attempters to depression or psychosis implies some degree of state-trait interaction (

figure 1). Hopelessness is greater in suicide attempters than in nonattempters during an acute depression (

83), after successful treatment (

86), and intermorbidly (

87). Hopelessness can predict future suicide (

47,

87,

88). These observations suggest that the degree of hopelessness is determined by both state and trait, and it may have predictive properties.

Genetic or familial factors contribute to suicide risk (

51,

52,

89). Aggression, impulsivity, and borderline personality disorder may also be results of genetic factors (

90–

94) or early life experiences, including a history of physical or sexual abuse (

95,

96). A common underlying genetic or familial factor, therefore, may explain the association of suicidal behavior with the aggression/impulsivity factor or borderline personality disorder. An indicator of genetic or familial risk is a history of suicidal behavior in a first-degree relative (

51). As evidence of this association, a higher rate of a positive family history of a suicide attempt or completion was associated with the presence of comorbid cluster B personality disorder (χ

2=5.08, df=1, p=0.02). This hypothesis of familial (perhaps genetic) transmission of a propensity for externally directed aggression and suicidal behavior, independent of transmission of major depression or psychosis, is consistent with evidence that suicidal behavior is transmitted in families independently of psychopathology but not independently of impulsive aggression(

97); it is also consistent with adoption studies reporting that transmission of a genetic risk factor for suicide that is independent of psychopathology (

50).

Suicide risk was also related to past head injury, as previously reported by others (

98–

101), and to a history of abuse in childhood (

95,

96) (

table 2). Both head injury and abuse in childhood were independent predictors of suicide status, and both were associated with the aggression/impulsivity factor. Higher scores on the aggression/impulsivity factor were found in patients with a past head injury (0.28 versus –0.19) (t=2.64, df=131, p=0.009) and in those with a history of abuse in childhood (0.33 versus –0.28) (t=3.20, df=106, p=0.002). In terms of causality, aggressive, impulsive children and adults are more likely to sustain a head injury, and head injuries can cause disinhibition and aggressive behavior (see reference

102 for review). Alternatively, mothers of abused children have an elevated suicide attempt rate and may transmit the risk for suicidal behavior both genetically and by upbringing. Aggressive, impulsive children may provoke child abuse in vulnerable parents and thereby create a tendency for self-injurious behavior in adult life (

95,

96).

Alcoholism and substance abuse are associated with suicidal acts and may be causal factors by increasing the probability of a head injury due to acute intoxication. Fifty percent of head injuries, which result in disinhibition and a greater probability of suicidal behavior (

103,

104), are sustained while using alcohol (

105). Alcoholism and substance abuse are related to the aggression/impulsivity factor and comorbid borderline personality disorder (which, in turn, can increase the risk for head injury as well as be aggravated by a head injury). Comorbid past alcoholism or substance abuse are associated with head injury (χ

2=11.96, df=1, p=0.001), with borderline personality disorder (χ

2=7.57, df=1, p=0.006), and with higher scores on the aggression/impulsivity factor (0.26 versus –0.44) (t=4.42, df=141, p<0.0001). This constellation of aggression, alcoholism, substance abuse, and impulsivity resembles a syndrome called “disinhibitory” psychopathology described by Gorenstein and Newman (

106) in a review of relevant clinical and animal studies of brain injury written almost 20 years ago.

Given the evidence linking low serotonergic activity separately to suicidal behavior (

107–

109), aggression, and alcoholism (see reference

82 for a review), it is conceivable that low serotonergic activity may, to some degree, underlie all three problems and that low serotonergic activity may mediate genetic and developmental effects on suicide, aggression, and alcoholism (

110). Reports of increased aggression, impulsivity, and cocaine and alcohol consumption in mutant mice lacking the 5-HT

1B receptor (

111,

112) indicate that a genetically mediated serotonin abnormality can result in increased impulsive aggression as well as alcoholism and substance abuse. Suicidal behavior is never observed in a rodent model, but the other elements of “disinhibitory” psychopathology are observed in this 5-HT

1B knockout mouse model.

Potentially related to the higher rate of substance abuse and alcoholism in the suicide attempters is our observation that cigarette smoking is more common in suicide attempters. Smoking is associated with elevated rates of suicide (

113–

117), and our study demonstrates that the association of smoking and suicidal acts is independent of any association of psychiatric illness with smoking. While this manuscript was under review, another study was published reporting an association of smoking and suicide attempts in patients with a variety of psychiatric diagnoses (

118).

The coexistence of a greater propensity for suicidal ideation and for impulsive behaviors in suicide attempters can partly explain why suicide attempters are prone to attempt suicide. They feel more suicidal and are more likely to act on feelings. These results suggest that clinicians should carefully assess severity of suicidal ideation and lifetime impulsivity or aggression in order to estimate the risk for future suicidal acts. This study, like most previous studies, evaluated associations with past suicidal acts. A prospective study is underway to determine correlates of future suicidal acts in the same patient population as part of an effort to develop a predictive model of suicidal acts.