The ability of customers to take business elsewhere is essential for the effective functioning of a free market. However, as first described by economist Albert O. Hirschman, consumer “exit” involves cost

(4). For a health care consumer, switching plans may require changing providers and learning to negotiate an unfamiliar system of care. We propose that depressive syndromes may raise the exit costs involved in disenrollment through two mechanisms. First, individuals with depressive symptoms are more likely than the general population to use, or expect to use, specialty mental health care. This multiplies the potential uncertainty and complexity involved in changing plans or providers. Second, the dependency, negative expectations, and “paralysis of the will” seen in depressive syndromes

(5) might make switching plans particularly difficult for depressed individuals. In either case, the higher cost of switching plans could reduce its effectiveness in ensuring quality of care.

This study used a national employee survey to explore the association between depressive symptoms, dissatisfaction, and plan switching. We tested the hypothesis that individuals with the highest levels of depressive symptoms are less satisfied with their care but are also less likely to switch plans when they perceive problems with their treatment.

METHOD

The data from this study come from the Employee Health Care Value Survey, fielded in 1993 by researchers from the New England Medical Center for a consortium of three major U.S. corporations

(6,

7). The sampling frame was constructed from lists of active employees provided by each corporation at the end of August 1993. These employees were enrolled in 46 health care plans located primarily in six geographic regions (New York City; Massachusetts/New Hampshire; Rochester, N.Y.; California; Tampa, Fla.; and Dallas/Houston). A random sample of those employees was mailed a 154-item survey containing questions about health status and satisfaction. The survey had been extensively pretested in a previous project

(8).

An established five-step, mail-out, mail-back procedure was used

(9), yielding a final mail survey completion rate of 63.5%. A comparison of responders to nonresponders indicated no statistically significant differences in income or race and minimal differences in age and gender. The final sample used in this study (

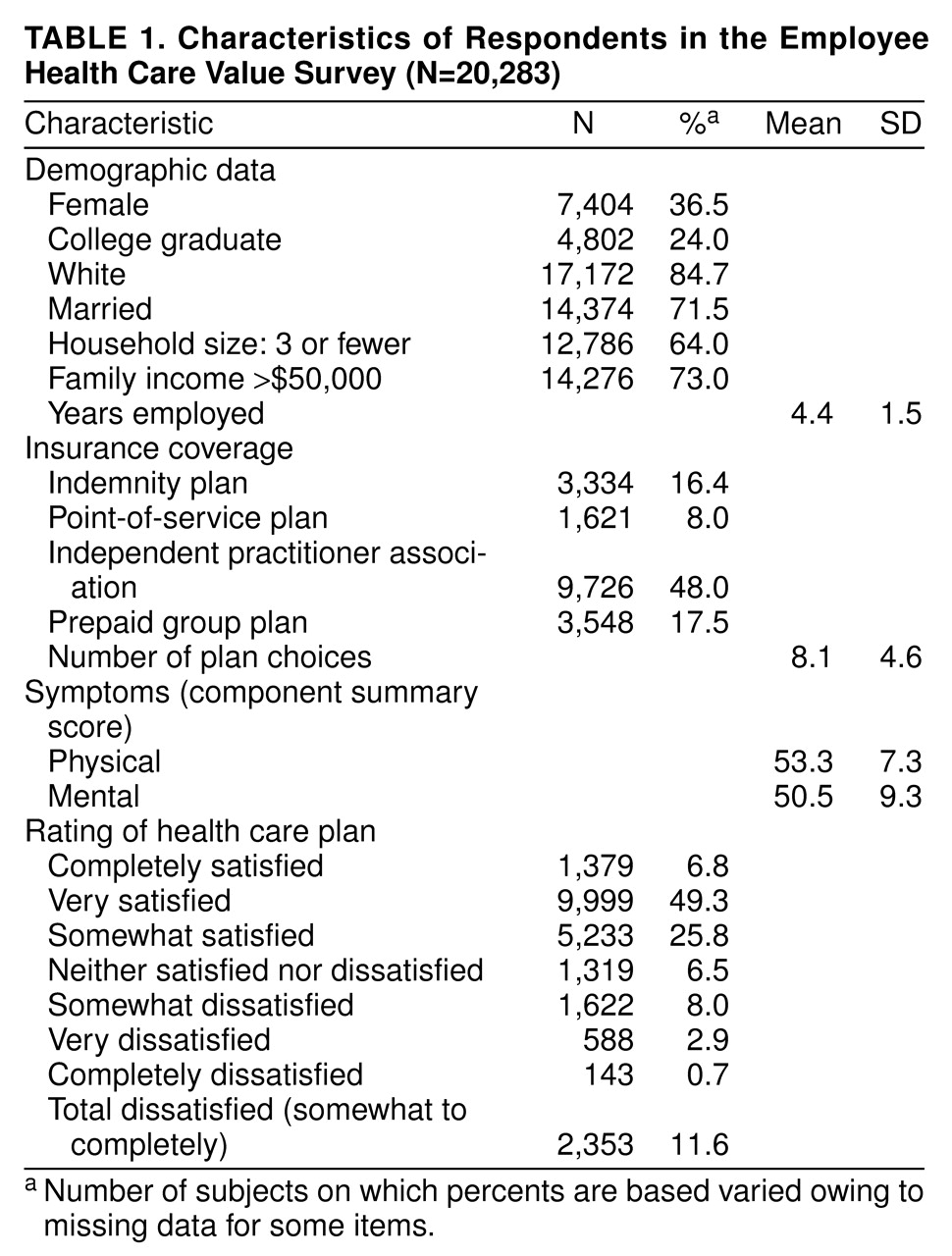

table 1) included all respondents to the mailed survey (N=20,283).

The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) is a health status measure constructed for use in the Medical Outcomes Study

(10). In using SF-36, studies have documented strong construct, convergent, and discriminant validity in distinguishing physical from mental disorders, as well as in differentiating milder from severe clinical depressive syndromes

(11).

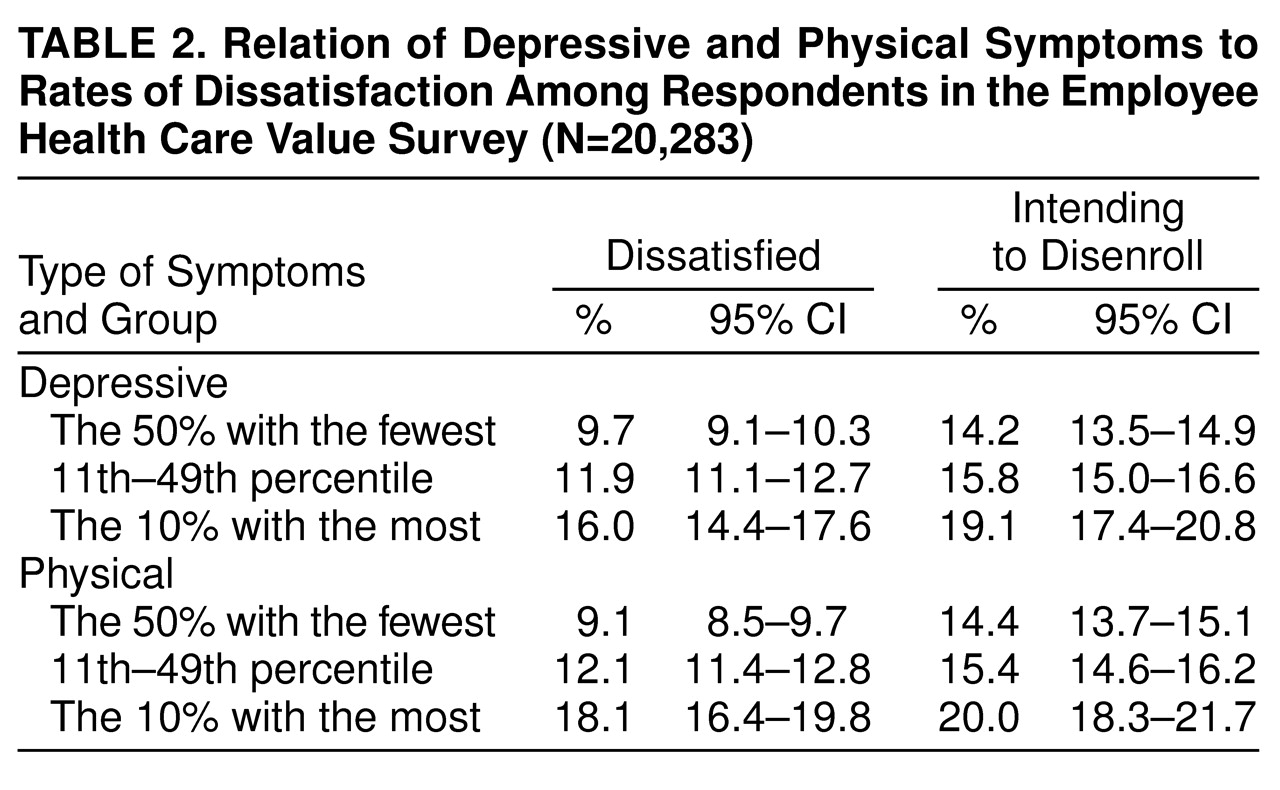

In order to assess the effect of differing levels of depressive symptoms on dissatisfaction and disenrollment, analyses compared individuals with the highest decile of symptoms on the mental component summary of the SF-36 (mental component summary score less than 37) to a “healthy” comparison group of the 50% with the fewest symptoms (mental component summary score greater than 53). For the physical component summary, the most symptomatic decile scored less than 44, and the “healthy” comparison group scored greater than 55.

The Employee Health Care Value Survey contained questions addressing overall satisfaction and 13 domains of satisfaction—six domains pertaining to provision of health care and seven related to plan administration. The number of items in each domain ranged from two to 11; all subscales had appropriate psychometric properties

(12).

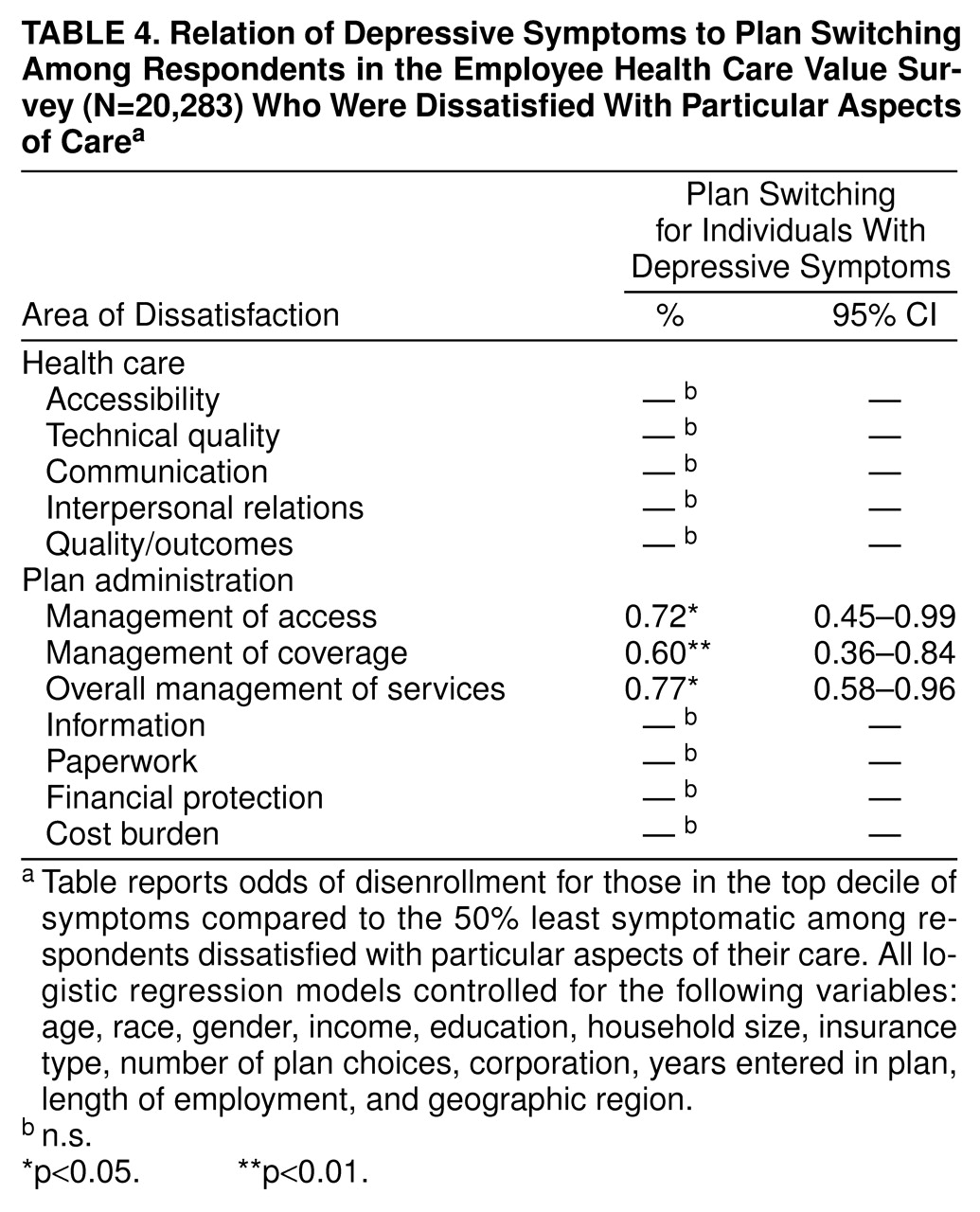

The measure of overall satisfaction asked respondents how satisfied they were with their plans on a 7-point scale, ranging from “completely satisfied” to “completely dissatisfied.” In addition to the global satisfaction question, respondents also were asked about 13 domains of satisfaction across two larger categories: health care delivery and plan administration. Health care delivery items included accessibility, technical quality, communication, choice and continuity, interpersonal care, and quality/outcome of care. Plan administration items included management of access (e.g., gatekeeping arrangements, delays in treatment approvals), management of coverage (e.g., utilization review), overall management of services, information, paperwork, financial protection (insurance coverage for medical expenses), and cost burden (out-of-pocket expenses).

Each scale was converted into a dichotomous measure that compared the individuals who reported dissatisfaction to the remainder of the sample. A total of 11.6% of the sample reported being somewhat, very, or completely dissatisfied with their overall care; 10%–20% of the sample reported dissatisfaction with each of the domains of care.

Respondents were also asked, on a 4-point scale, whether they intended to disenroll from their plans (“definitely does not intend” to “definitely does intend” to switch plans). This result was converted to a dichotomous variable for the purposes of the study (“intends to disenroll” or “does not intend to disenroll”). Actual disenrollment in the year after the survey was administered was obtained from administrative data.

In order to understand the relationship between symptoms, satisfaction, and plan switching, it was essential to control for other factors that could influence either enrollee satisfaction or plan selection. Research has demonstrated that reported levels of satisfaction are associated with a variety of sociodemographic characteristics

(13–

15). Therefore, models controlled for age, gender, educational attainment, marital status, and the size and income level of the respondent’s household. We included length of enrollment in the current health plan in models because enrollees who have been affiliated with a plan longer have been found to report higher levels of satisfaction with that plan

(16). Finally, because satisfaction with managed care has been shown to be substantially higher for enrollees who have had a choice among plans

(17), we included a proxy measure for plan choice by counting the number of plans chosen by enrollees for any given corporation in any given region.

A first set of analyses examined the rates of dissatisfaction and intent to disenroll for individuals in each group of depressive and physical symptoms.

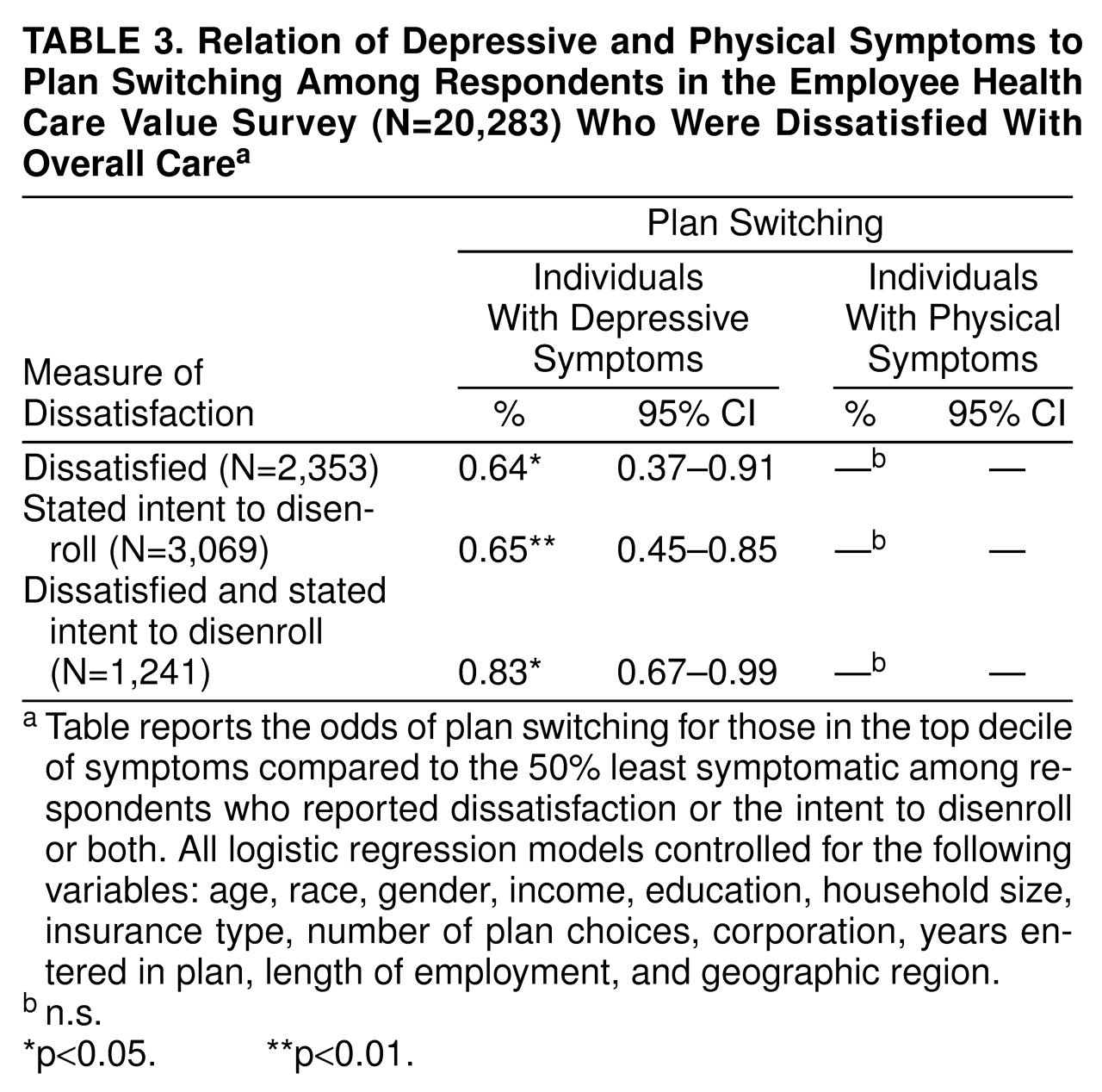

The remainder of the analyses focused on plan switching. These analyses examined only individuals who reported dissatisfaction or the intent to disenroll, since we were interested in studying people who had disenrolled because of problems with their plans, as opposed to those who had changed plans for other reasons (e.g., because they switched jobs). Logistic regression was used to model disenrollment as a function of the presence of high levels of physical or depressive symptoms. Each model included both depressive and physical symptom measures to isolate the effects of each type of symptom while controlling for the other. All models also controlled for age, race, gender, income, household size, insurance type, number of plan choices, corporation, years entered in the plan, length of employment, and geographic region.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study confirm our initial hypothesis that depressive symptoms were associated with dissatisfaction with health care but with a lower likelihood of an enrollee acting on that dissatisfaction by switching plans. We did not find a comparable effect for physical symptoms, although we report elsewhere that serious or debilitating medical conditions may inhibit dissatisfied enrollees’ ability to switch from particular types of health plans

(18).

For this population, depressive and physical symptoms had a comparable association with dissatisfaction. Previous literature suggests that dissatisfaction in people with psychological distress does not simply reflect the fact that they are “dissatisfied people”

(19). However, understanding the link between psychiatric morbidity and dissatisfaction can be complex

(20). At least one explanation may be that sicker enrollees have greater exposure to the health care system than healthier enrollees and consequently more knowledge of the ways in which their plan limits access to care. Certainly, enrollees with depression are more likely to be familiar with the mental health services offered by a plan than the general population.

Despite relatively high levels of dissatisfaction, people in the top decile of depressive symptoms were about one-third less likely to disenroll when dissatisfied or when they had expressed an intention to do so as compared to the remainder of the sample. Here, too, there may be some tendency to dismiss the lack of disenrollment among patients with depressive symptoms as evidence that their expressed concerns were not serious. But the differential results among subdomains of satisfaction suggest an alternative explanation. For administrative domains, including utilization review (management of coverage) and the requirement of gatekeeper approval (management of access), people with depressive symptoms appeared to be significantly inhibited from disenrolling. This gap was not evident for either interpersonal or technical aspects of health care. Thus, people with depressive symptoms may be willing to tolerate relatively high levels of dissatisfaction with administrative aspects of their care in order to preserve continuity with providers or because they perceive even greater potential barriers if they were to switch to another plan. For these administrative aspects of care provision, plan switching appears to provide the weakest protection for people with depressive symptoms.

Three solutions have been proposed to address the potential market failure associated with difficulties in plan switching. First, some authors have asserted that the market may be in the process of correcting itself through the increasing use of mental health “carve outs” in both the public and private sectors

(21). By offering specialized managed care networks with expertise in mental disorders, these arrangements may offer some advantages to individuals with mental disorders

(22). However, uncoupling mental health coverage from general health benefits might also exacerbate problems with plan choice for people with mental disorders. Selecting a health plan on the basis of mental health coverage may be confusing when those benefits are carved out, particularly when a plan can switch to another mental health provider with little notice.

The second option for addressing the issue of selective disenrollment is to provide governmental regulation. Congress has passed several bills in the past year that seek to address perceived deficiencies in the health care market for people with chronic illnesses

(23). An amendment supporting parity between mental health and physical benefits became effective in 1998

(24). However, even in a system with parity-of-benefits packages, administrative barriers may still create obstacles to switching plans for people with mental disorders when their care is inadequate

(25).

The third possible solution for addressing the problems underlying selective disenrollment is to strengthen the grievance mechanisms by which dissatisfied enrollees can voice their concerns. Enhancing grievance mechanisms is one of the cornerstones of proposals for a “patient’s bill of rights” for health care

(26). But the same difficulties that inhibit disenrollment among depressed individuals might also impair their ability to effectively express their dissatisfaction through such grievance mechanisms. Further work is needed to understand whether consumer voice can be an effective means of ensuring quality of care for individuals with depressive symptoms.

The Employee Health Care Value Survey poses several limitations for studying the issue of depressive disorders and plan switching. First, we had access to a measure of depressive symptoms rather than a diagnostic assessment for depressive disorders. Further work needs to assess this study’s findings for individuals with clinically diagnosed major depression, as well as for other psychiatric disorders. Second, we did not have information about what types of medical or mental health services these individuals received. A richer understanding of the processes underlying dissatisfaction and plan switching would be provided if it were possible to identify which individuals had actually received mental health services and which types of providers (e.g., generalists, psychiatrists, or other mental health specialists) provided those services. Finally, because this study examined an employed population, its results cannot necessarily be generalized to elderly, poor, or uninsured populations. However, barriers to disenrollment may increasingly become a concern in the public sector as the federal and state governments look to managed care to control the rising costs of Medicare and Medicaid

(27–

29).

This study provides preliminary evidence that individuals with depressive symptoms may be particularly vulnerable to certain forms of market failure under managed care. Further research is needed to confirm this finding in different populations and settings, identify particular groups at risk, and study potential solutions.