During the last several decades, evidence has accumulated that schizophrenia is associated with significant impairment in cognitive functioning. Specifically, deficits in attention, memory, and executive function have been consistently reported in patients with schizophrenia

(1–

3). In contrast, formal assessment of perceptual processes and basic language function does not show gross impairment

(3). Memory has been regarded as one of the major areas of cognitive deficit in schizophrenia

(4). Although the pioneers of schizophrenia research, Kraepelin

(5) and Bleuler

(6), considered memory functions to be relatively preserved in schizophrenia, numerous studies conducted in the second half of this century have shown that patients with schizophrenia perform poorly on a wide range of memory tasks

(3,

7,

8). Studies indicate memory impairment in schizophrenia to be common and disproportionate to the overall level of intellectual impairment

(9,

10). McKenna and colleagues

(11) have even suggested existence of a schizophrenic amnesia.

However, other authors consider the memory impairment to be relatively small in magnitude or secondary to attentional dysfunction

(12–

15). In addition, the specificity of memory impairment in schizophrenia is unclear. It has been suggested that, in schizophrenia, some aspects of memory may be affected to a greater extent than others. This would be the case, for example, in active retrieval (free recall) of declarative information from long-term memory, which would be significantly more impaired in individuals with schizophrenia than retrieval from short-term memory—e.g., digit span

(16). Also, some authors have proposed that encoding of information may be more affected than memory processes such as retrieval and recognition

(17,

18). In contrast, other studies report that the memory deficit in schizophrenia encompasses a broad range of memory processes, as evidenced by poor scores in multiple task paradigms

(7,

10,

19,

20).

Other important issues regarding schizophrenia and memory performance that remain unclear are whether memory functioning in schizophrenia is stable over time, whether chronic patients with schizophrenia exhibit greater memory impairment than acutely ill patients, and whether the effects of medication may account for a significant portion of the observed memory impairment.

Meta-analysis represents a type of review that applies a quantitative approach with statistical standards comparable to primary data analysis. A meta-analytical approach has several advantages above traditional narrative methods of review. By quantitatively combining the results of a number of studies, the power of the statistical test is increased substantially. Also, studies are differentially weighted with varying group size. Finally, by extracting information quantitatively from existing studies, meta-analysis allows one to examine more precisely the influence of potential moderators of effect size.

The aim of the present study was twofold. The first goal was to determine the magnitude, extent, and pattern of memory impairment in schizophrenia by meta-analytically synthesizing the data from studies published during the past two decades. The second purpose was to examine the effect of potential moderator variables, such as clinical variables (e.g., age, patient status, and medication) and study characteristics (e.g., matching of comparison subjects and year of publication), on the association between schizophrenia and memory impairment.

METHOD

Literature Search

Articles for consideration were identified through an extensive literature search in PsycLIT and MEDLINE from 1975 through July 1998. The key words were “memory” and “schizophrenia.” The search produced over 750 unique studies. Titles and abstracts of the articles were examined for possible inclusion in our analysis. Additional titles were obtained from the bibliographies of these articles and from a journal-by-journal search for all of 1997 and the first half of 1998 for journals that we suspected most frequently publish articles in the targeted domain. This strategy was adopted to minimize the possibility of overlooking studies that may not yet have been included in computerized databases. The journals included the following: American Journal of Psychiatry, Archives of General Psychiatry, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Psychological Medicine, Schizophrenia Bulletin, and Schizophrenia Research.

The identified studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria. First, each study had to include valid measures of explicit memory performance. We included the following paradigms: digit span (forward and backward), cued and free list recall and word list recognition, paired-associate recall, prose recall, and nonverbal (visual pattern) recall and recognition. Second, studies had to compare the performance of healthy normal comparison subjects with the performance of patients with schizophrenia. Studies with a comparison group consisting of nonpsychotic subjects with a higher risk for schizophrenia (e.g., first-degree relatives or subjects with schizotypal traits) were not included in the analyses. Finally, studies had to include sufficient data for the computation of a d value, which implies that means and standard deviations, exact p values, t values, or exact F values and relevant means should be reported. We obtained the results of 70 studies

(9,

10,

15,

16,

19–

84) that met the criteria for inclusion in our meta-analysis.

Data Collection and Analysis

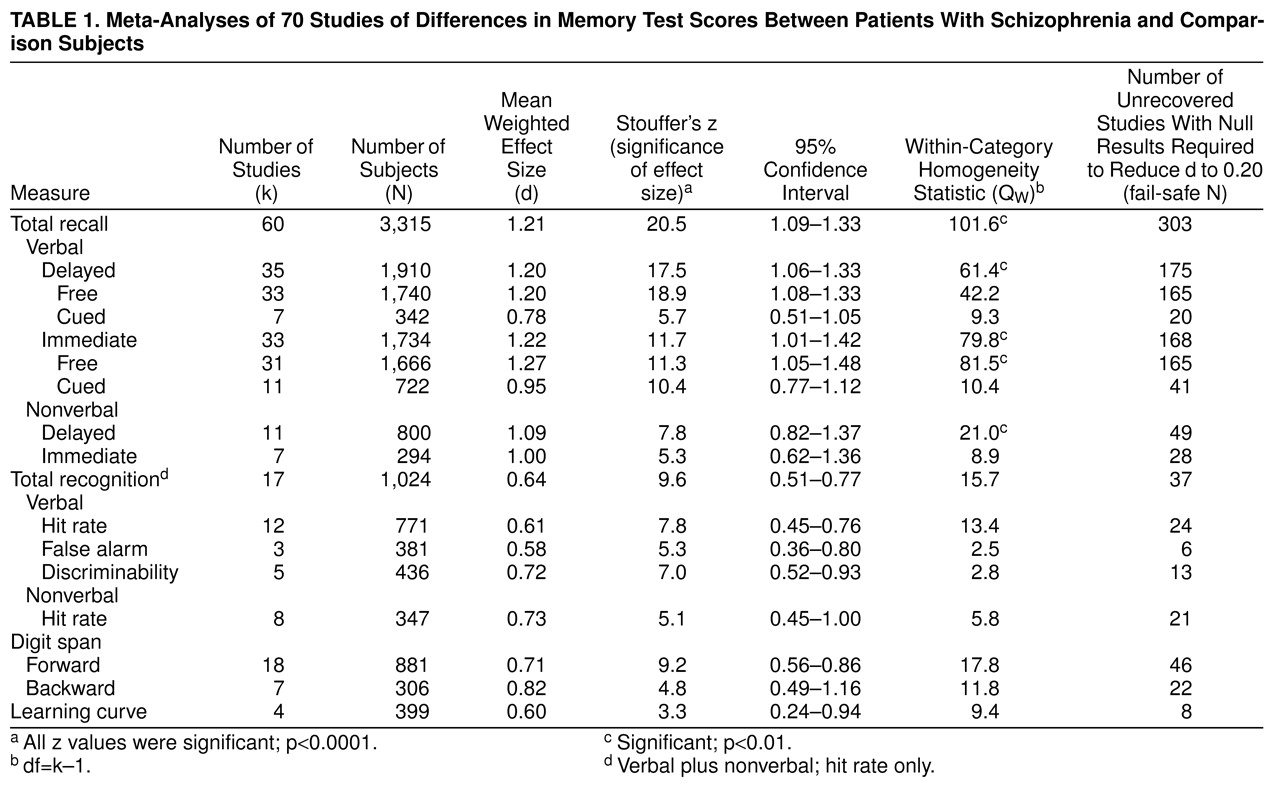

By comparing measures of free recall, cued recall, and recognition, we examined the effect of retrieval support on memory performance between patients with schizophrenia and normal comparison subjects. In free recall measures, retention is measured in the absence of any cues, whereas in cued recall tests, a portion of the encoding context is presented at the time of retrieval. In recognition, the target material is presented along with distracters, and the subject is required to differentiate between target material and distracters. The learning curve refers to the increase in recall of information with different learning trials. Furthermore, we investigated the influence of the nature of the stimuli used in the memory tasks (verbal versus nonverbal). Finally, we evaluated the role of the retention interval, which could be assessed immediately after presentation of the to-be-learned material or after a delay.

From the data reported in each study, we calculated effect sizes for the difference in memory performance between patients with schizophrenia and comparison subjects. The effect size estimate used was Hedges’s g

(85), the difference between the means of the schizophrenic group and the comparison group, divided by the pooled standard deviation. From these g values, an unbiased estimation, d, was calculated to correct for upwardly biased estimation of the effect in small group sizes

(85,

86). The direction of the effect size was positive if the performance of the patients with schizophrenia on memory measures was worse than that of the comparison subjects.

The combined d value is an indication of the magnitude of associations across all studies. In addition to d, we calculated another statistic, Stouffer’s z, weighted by group size, with a corresponding probability level

(86). This statistic provided an indication of the significance of the difference between memory performance in the schizophrenic group and the comparison group and thus indicated whether the results could have arisen by chance. We also calculated a chi-square statistic, Q, indicating the homogeneity of results across studies

(87). The significance of the Q statistic pointed to the heterogeneity of the set of studies, in which case a further search of moderator variables was needed. In the moderator analyses, Q

W denoted the heterogeneity of studies within categories. The Q

B statistic refers to a test of differences between categories. This between-group homogeneity statistic is analogous to the F statistic. All analyses were performed with the statistical package META

(88).

When more than one dependent measure was used as an indication of memory performance, a pooled effect size was computed to prevent data from one study from dominating the outcome of the overall meta-analysis. For example, in studies reporting data on free and cued recall of verbal and nonverbal stimuli, for each study, a combined d was calculated for inclusion in the overall analysis. However, in subsequent analyses, we included only the data pertaining to the specific category of our aim. Thus, for example, in the meta-analysis of differences between patients with schizophrenia and comparison subjects in cued recall performance, only data of cued recall measures were included in the analysis. Similarly, when a study reported data for subgroups such as patients with first-episode schizophrenia versus patients with chronic schizophrenia, in the overall analysis, the d values were pooled, but in the moderator analysis of duration of illness, the d values were included separately in the analysis.

In the case of twin studies (e.g., Goldberg et al.

[48]), the patients were compared with normal twins. Thus, the unaffected siblings of identical twins discordant for schizophrenia were not included in the analyses. Furthermore, in studies in which data were reported for different subgroups (e.g., men/women, paranoia/nonparanoia), data were pooled across subgroups, which were then compared as one group with the performance of the comparison group.

When we encountered different studies in which data concerning the same group of subjects were reported, only one of the studies was included in the analysis to avoid the problem of dependent data (i.e., to prevent one group from dominating the outcome). For example, the subjects of the 1990 study by Goldberg et al.

(89) were included in their 1993 study

(48) as well. We included only the 1993 study

(48) in the analysis because the group in that study contained more subjects than the group in the 1990 study

(89).

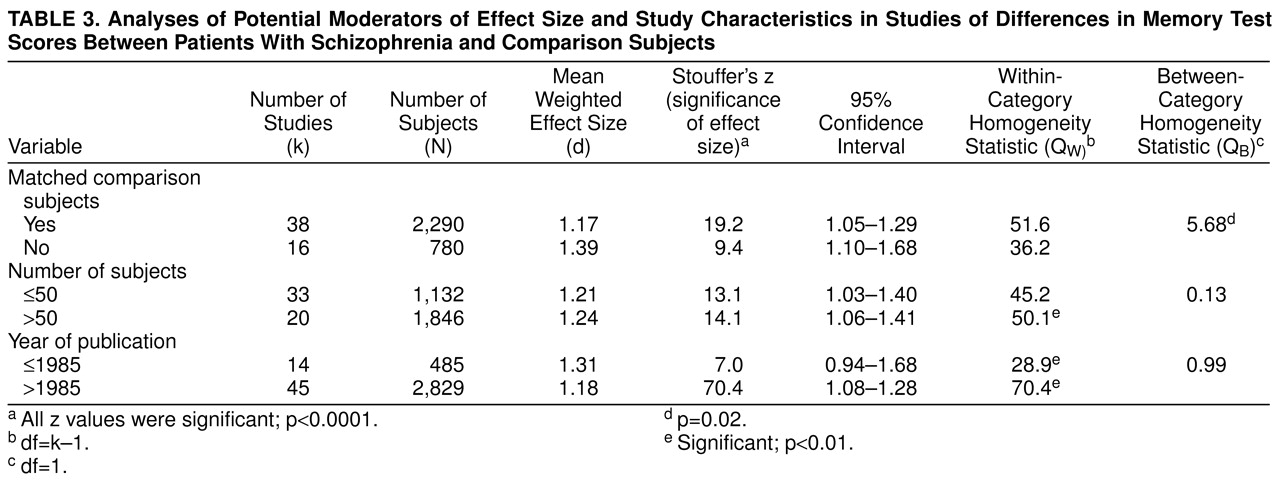

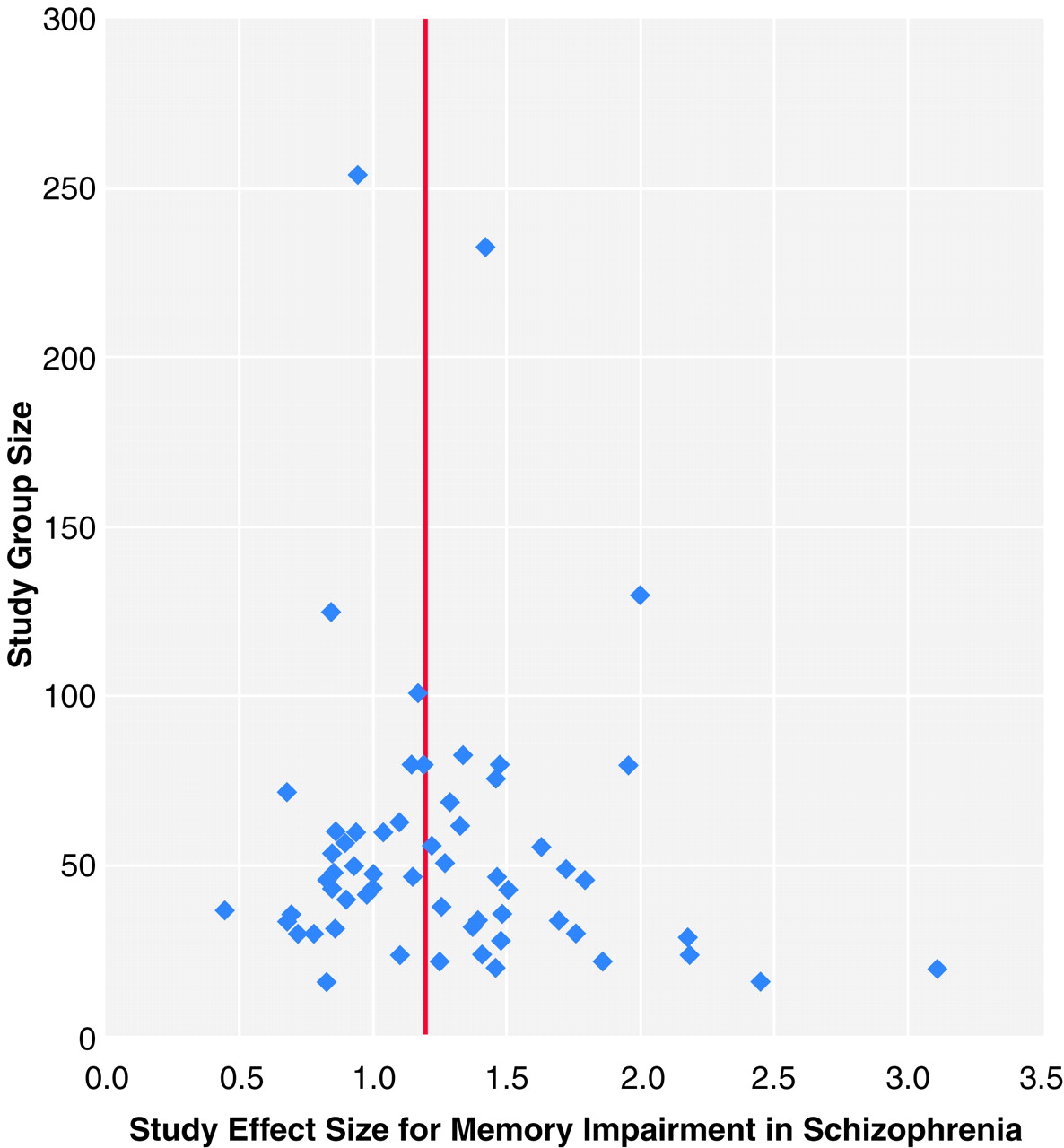

Publication Bias

To examine the possibility of publication bias, we computed a fail-safe number of studies

(86,

90). Publication bias implies that studies with no effect may not be published and may remain in file drawers, posing a threat to the stability of the obtained effect size. The fail-safe number of studies statistic indicates the number of studies with null effects that must reside in file drawers before the results of the obtained effect sizes are reduced to a negligible level (which we set at 0.2). Publication bias can also be inspected graphically in a funnel plot

(91). The total group size of each study is plotted with its effect size. Because larger studies have more influence on the population effect size, small studies should be randomly scattered about the central effect size of larger studies. Thus, scatter will increase when study size decreases, which gives rise to an inverted funnel appearance. When the portion of the funnel near effect size 0.0 is not present, it may be an indication of publication bias because studies with nonsignificant effects and small group sizes remain unpublished.

Moderator Variables

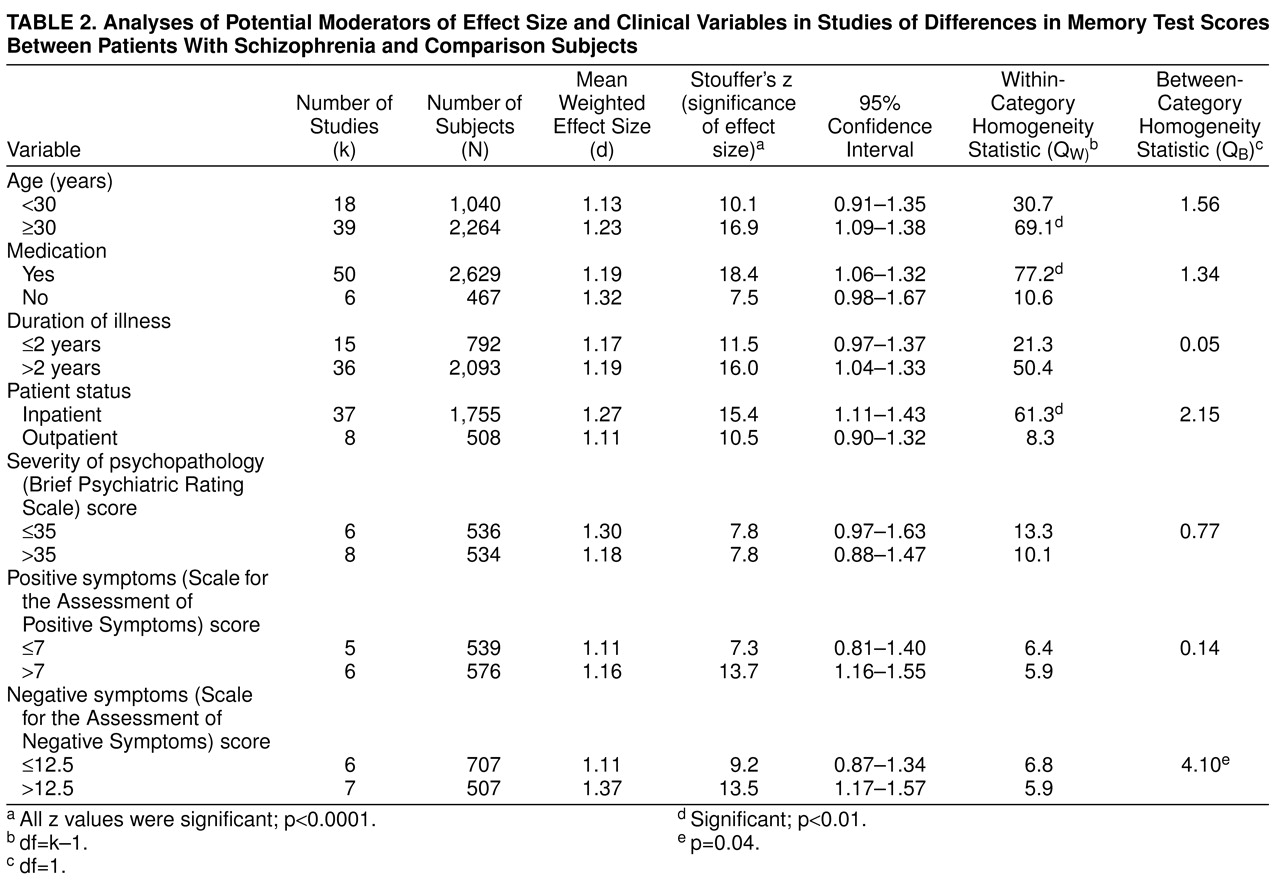

The literature suggests a number of variables that may affect the memory performance of patients with schizophrenia. We evaluated the potential influence on effect size of several such factors, using categorical models. The moderator variables we studied can be divided into two groups: clinical variables and study characteristics. The clinical variables included age of subjects, patient status (inpatient or outpatient), medication status, duration of illness, severity of psychopathology, and the influence of positive and negative symptoms. For the analysis of severity of psychopathology, we included only studies reporting Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores. Other psychopathology measures, such as the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale, were not included because of a lack of studies. For positive and negative symptoms, the scales included in the analysis were the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms and the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms. The groups were divided by means of a median split.

Study characteristics were year of publication (before and after 1986, the median year of the period covered in the literature search), group size, and whether schizophrenic and comparison groups were matched for age and level of education. Unfortunately, sex differences, differential performance of diagnostic subgroups (e.g., paranoia/nonparanoia), task difficulty and reliability, and the moderating effects of attentional dysfunction could not be studied, because of the very small number or total lack of studies reporting exact results for these parameters.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether and to what extent schizophrenia is associated with memory impairment and whether this association is influenced by potential moderator variables. The results of the meta-analysis indicate that schizophrenia and memory dysfunction are significantly associated, as evidenced by moderate to large effect sizes. Our meta-analysis corroborates and extends the findings of a recent meta-analysis (92), in which performance on multiple measures of neurocognitive function was contrasted between patients with schizophrenia and normal comparison subjects. With regard to differences in memory performance, Heinrichs and Zakzanis

(92) also reported moderate to large effect sizes for the memory variables they studied, which included verbal and nonverbal long-term memory.

The d for recall was 1.21, which indicated a large effect size, according to the nomenclature of Cohen

(93). Thus, the performance of patients with schizophrenia was more than 1 standard deviation lower than that of normal comparison subjects on tasks of recall memory. A recent meta-analysis of memory impairment in depression

(94) revealed a d of 0.56 (54 studies) for the recall performance of patients with depression compared with normal subjects. When these results are compared with our present analysis, the memory deficit in schizophrenia appears to be substantially greater than in depression. The d for recognition was 0.64, which can be considered a moderate effect size

(93). The difference in recall versus recognition performance may point to a retrieval deficit, in addition to a less effective consolidation of material. Alternatively, the recall-recognition difference may be an artifact of the differences in difficulty between the recall and recognition tests. However, studies in which tasks were matched for difficulty level also showed greater impairment in recall than recognition

(34,

35). The finding of a considerable memory deficit in schizophrenia supports the view that memory belongs to the cognitive domains, which show major impairment in schizophrenia

(3,

4). However, the lack of difference between immediate and delayed recall does not appear to be in accordance with schizophrenia as an amnesic syndrome

(11). Measures of short-term memory performance showed significant impairment. This result appears to contradict the assertion by Clare et al.

(41) that short-term memory is preserved in schizophrenia. The divergence may result from the fact that Clare et al. based their conclusion on one study only, whereas the present study concerns a quantitative integration of multiple studies. Furthermore, our meta-analysis provides evidence that the learning curve (which reflects explicit encoding of information) is significantly affected in schizophrenia. The large difference between recall of information after a delay (composite delayed recall: d=1.20) and recall in the learning curve (d=0.60) suggests that the memory dysfunction in schizophrenia is not entirely caused by deficient learning processes (as was argued by Heaton et al.

[17]) but that retrieval processes may also be affected. However, caution is needed in interpreting this finding, considering that digit span and learning curve indices may not reflect all encoding processes.

The results failed to reveal a difference in memory impairment between verbal and nonverbal (visual pattern) stimuli. Thus, the memory impairment in schizophrenia does not appear to be modality specific.

The present meta-analysis indicates memory impairment in schizophrenia to be wide ranging and consistent across task variables, such as level of retrieval support (free recall, cued recall, or recognition), stimulus type (verbal versus nonverbal), and retention interval (immediate versus delayed). The extent of the memory impairment may appear to be in accordance with a pattern of generalized dysfunction rather than a differential deficit

(26). However, our study was restricted to memory functions, whereas conclusions regarding the generalized versus differential nature of neurocognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia must also include evaluation of functioning in other cognitive domains. Indeed, the recent meta-analysis by Heinrichs and Zakzanis

(92), in which schizophrenia and comparison group differences were indexed on multiple measures of memory, attention, intelligence, executive function, language, and motor performance, indicated that schizophrenia is characterized by a broadly based cognitive impairment, with varying degrees of deficit in the different ability domains.

On the basis of our results, it is not possible to establish the cause or underlying mechanism of the memory impairment in schizophrenia. For example, we were not able to examine the moderating effects of attentional dysfunction. However, given the magnitude and extent of the memory impairment revealed by the meta-analysis, the possibility that the memory impairment may be secondary to attentional dysfunction does not seem very plausible. Moreover, in cases of an important attentional contribution to the memory impairment, one would expect performance on the backward digit span test to show a significantly greater impairment than that on the forward digit span test. This was not the case, however. Our findings are in agreement with those of Kenny and Meltzer

(57), who controlled for the influence of attention by an analysis of covariance. Controlling for attention had very little effect on the differences in performance on long-term memory recall between patients with schizophrenia and comparison subjects.

Although the meta-analysis did not address the relation between memory impairment and brain pathology in schizophrenia, the pattern of impairment may be indicative of specific brain dysfunction. Impairments in encoding and consolidation have been associated with hippocampal and temporal lobe dysfunction

(95,

96). Brain imaging studies have provided evidence for pathology or reduced volume in these structures in schizophrenia

(97). In addition, frontal lobe systems, which may also be affected in schizophrenia, have been shown to be involved in the active retrieval of declarative memories

(98,

99). More research into the relation between brain dysfunction and memory impairment in schizophrenia is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn on this issue.

Of the potential moderator variables, only negative symptoms affected the schizophrenia-memory association. Although this effect was rather small, it was consistent with previous research examining the relation between negative symptoms and cognitive function in schizophrenia

(100,

101). Specifically, negative symptoms have been associated with more pronounced frontal lobe dysfunction, which may account for larger retrieval deficits

(101). No relation was found between age and the magnitude of memory impairment. Unfortunately, because all subjects included in the analyses were less than 45 years old, no conclusions can be made regarding the relation between cognitive aging and memory in schizophrenia.

Clinical variables such as medication, duration of illness, patient status, severity of psychopathology, and positive symptoms did not appear to influence the magnitude of memory impairment. Thus, the memory impairment in schizophrenia is of a considerable robustness and is not readily moderated by variables that may seem relevant. This is an important finding, because a number of authors have emphasized the role of medication, symptom severity, and chronicity in the memory performance of patients with schizophrenia

(8,

27). Frith

(102) even suggested that medication may principally account for the memory deficits observed in schizophrenia. It is instructive to note that our meta-analysis does not address the relation between medication and memory performance directly but compares the performance of unmedicated groups with that of medicated groups. Differences in medication status may be caused by unspecified differences in clinical factors. Our results are consistent, however, with studies examining this relation directly, by experimentally controlling for medication use

(103,

104). It must be emphasized that medication in the studies in our analysis consisted of conventional neuroleptics. Evidence is emerging that novel antipsychotics may have beneficial effects on memory function

(105).

As the present meta-analysis demonstrates, there is no evidence of progressive decline associated with age or duration of illness in schizophrenia. Our failure to find an effect of chronicity on memory impairment is in accordance with the view of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia as a static encephalopathy

(47). The fact that patients with schizophrenia with a long duration of illness do not perform worse than more acutely ill patients on memory tasks implies that the concept of dementia praecox

(5) may not be accurate in the sense of progressive deterioration during the long-term course of the illness. On the other hand, considering the substantial memory deficit in schizophrenia revealed by our analysis, the term “dementia praecox” may be even more appropriate than Kraepelin himself may have anticipated.

The findings of our meta-analysis have important clinical implications. The substantial memory deficit in schizophrenia is likely to have repercussions on therapy and rehabilitation. A thorough understanding of the cognitive deficits in schizophrenia may prevent the failure of future treatments

(106). For example, insight-related or other therapies that require advanced learning and memory functions are almost certain to be ineffective.

The extent and stability of the association between schizophrenia and memory impairment suggest that the memory dysfunction may be a trait rather than a state characteristic. Hypothetically, some degree of memory dysfunction may already be present in subjects at risk for schizophrenia. Future research must concentrate on this issue to explore the possible implications with regard to prescreening for schizophrenia.

There is evidence that verbal memory is a rather strong predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia

(107). Improving memory may be beneficial for everyday functioning. Therefore, given the considerable memory impairment revealed by our meta-analysis, research focusing on pharmacological treatment and rehabilitation strategies to improve memory functioning in patients with schizophrenia is necessary.