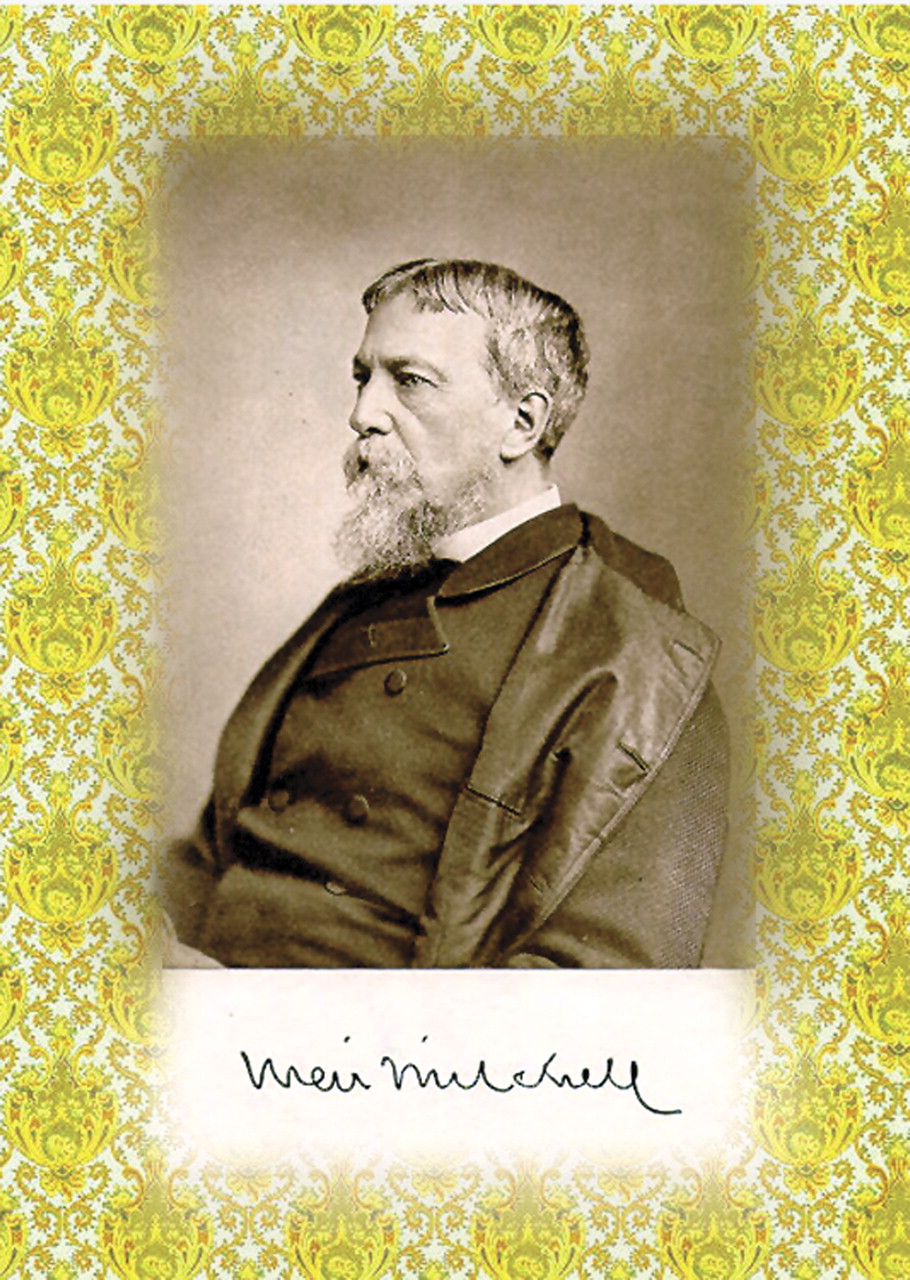

To understand the struggle between the two extraordinary personalities of

S. Weir Mitchell and Charlotte Perkins Gilman, it is necessary to understand the radical nature of the rest cure itself.

Mitchell’s treatment was designed for neurasthenics, whom he described as “nervous women, who, as a rule, are thin and lack blood” (

1, p. 9). At the time, “neurasthenia” was a catch-all diagnosis for the host of nonpsychotic emotional disorders that were not understood and not responsive to medical therapies. The number of textbooks describing the rest cure after

Fat and Blood was published makes clear how eagerly the medical establishment embraced the new therapy.

The cure, which was prescribed almost exclusively for women, had three core elements: isolation, rest, and feeding, with electrotherapy and massage added to counteract muscle atrophy. While Mitchell outlined his methods in

Fat and Blood, he and many other neurologists refined the details as time went by. The patient was instructed to lie in bed for 24 hours each day, sometimes for months at a time, with a special nurse who would sleep on a cot in the room, feed her, and keep her mind from morbid thoughts by reading aloud or discussing soothing topics. Visits from family and friends were forbidden. The day was punctuated by electrotherapy and massage, sponge baths with a “rough rub” using wet sheets, and frequent feedings. The diet consisted of milk alone for the first week, or, if milk was not tolerated, 18 or more raw eggs per day (

2, p. 49). Detailed dietary instructions were also provided for the obese patient, in those days the exception rather than the rule. The patient would pass into a state of placid contentment, described by several contemporaneous textbooks: “Brain work having ceased, mental expenditure is reduced to a slight play of emotions and an easy drifting of thought” (

2, p. 44). The fat would “roll up in the face, and subsequently over the body” (

3, p. 140). When restlessness set in, exercise would be gradually introduced and the patient would eventually resume communication with her family and return to a healthy lifestyle. For Mitchell, at least, “healthy” for women included strict limits on “brain work,” which he felt imposed nervous strain and might interfere with “womanly duties.”

Psychological manipulation was crucial to the rest cure, as Mitchell was well aware. Indeed, he wrote that his success rested in large part on “the moral methods of obtaining confidence and insuring a childlike acquiescence in every needed measure” (

1, p. 99). Some practitioners differentiated among patients. For example, Charles Dana noted that the “active, keen-witted, intellectual woman…does not do so well under a method which for a time renders them abulic” (

4, p. 594). This kind of psychological nuance is lacking in Mitchell’s writing. In fact, every now and then a note of contempt creeps into his descriptions of his neurasthenic patients: “She was a pallid, feeble creature…and had no more bosom than the average chicken of a boardinghouse table. Nature had wisely prohibited this being from increasing her breed” (

5, p. 132). Perhaps Charlotte Perkins Gilman, despite being vigorous and good-looking, sensed this hostile side of Mitchell, or perhaps her personality triggered it. If so, she was an exception. Most of the time, his “moral methods” were facilitated by his personal charisma. The quantity of mail he received from his adoring female patients attests to the fact that he was “electric with fascination” (

6, pp. 160–161). He was also a domineering personality and could be harsh and unorthodox, for example, “encouraging” exercise by driving one woman far from home so she would be forced to walk back. A frequently repeated anecdote, possibly apocryphal, is that he rousted one patient out of bed by threatening to climb in with her.

Opposed to this brilliant, sometimes arrogant physician was Charlotte Perkins Gilman, a mostly self-educated artist, writer, and reformer, who championed the rights of women to intellectual and economic equality, as well as other reformist causes ranging from socialism to “child culture” to physical education for men and women. All her life she suffered from bouts of “black empty days and staring nights” (

7, p. 104). In an article called “Why I Wrote ‘The Yellow Wallpaper,’” published in 1913, a year before Mitchell’s death, she recounted how she spent 3 months trying to follow his prescription for “a domestic life” and “came so near the borderline of utter mental ruin that I could see over.” She credited her escape partly to freeing herself from her marriage and partly to casting aside Mitchell’s suffocating advice. Indeed, she wrote “The Yellow Wallpaper” to communicate to Mitchell (and perhaps on some level to her husband) how close to the edge of madness she had come because of the prohibition against work. Years later she was gratified to hear, through friends, that the great neurologist had modified his treatment of neurasthenia after reading her story.

Gilman’s short story highlighted the rest cure as a symbol of the paternalistic nature of 19th-century medicine and the suppression of female creativity. Yet reading the careful instructions and closely observed case studies of the physicians using this new therapy, one is touched by their enthusiasm. Finally, they felt, they had something to offer patients whose suffering had seemed incurable. The best practitioners of the cure paid scrupulous attention to every detail of the patient’s comfort, both of mind and body. Still, the implicit prejudices inherent in the rest cure are clear. The patient was to be infantilized and confined for her own good, and the cost, as “The Yellow Wallpaper” shows, could be devastating. In the confrontation between S. Weir Mitchell and Charlotte Perkins Gilman, one can see a 19th-century microcosm of the tension between beneficence and autonomy. This tension persists in psychiatry today.