No single treatment is a panacea for major depressive disorder. A wide variety of treatments are available, but many patients do not achieve a satisfactory outcome with an adequate implementation of their initial treatment, and a subsequent treatment is required. Second-step treatments take the form of either an augmentation strategy, in which a second treatment is added to the initial treatment, or a switch strategy, in which the initial treatment is discontinued and a different treatment is initiated. Various treatment guidelines

(1) and algorithms

(2,

3) have been formulated to assist clinicians in selecting, implementing, and changing

(4) treatments. In addition, the relationship between patients’ treatment preferences and retention and symptomatic outcome has been studied

(5), but little is known about what factors are associated with patients’ willingness to accept a given second-step treatment strategy for depression. The purpose of this study was to determine which sociodemographic and first-step treatment-related factors are associated with patients’ acceptance of second-step treatments for major depressive disorder.

This study was conducted as part of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial

(6,

7) . STAR*D was designed to define prospectively which of several treatments are most effective for participants with major depressive disorder who had an unsatisfactory clinical outcome after an initial treatment and, if necessary, subsequent treatments. The study used an equipoise-stratified randomized design

(8) that allowed participants (with input from their clinicians) to select randomized assignment to any treatment within the following strategies for their second-step treatment: an augmentation strategy only (with or without cognitive therapy), a switch strategy only (with or without cognitive therapy), both augmentation and switch strategies (with or without cognitive therapy), or cognitive therapy only (including both switch and augmentation strategies).

Because STAR*D’s design incorporated participant choice, the trial offered a unique opportunity to identify factors associated with participants’ selections of second-step treatment. In this study, we addressed the following questions:

1. Do patients who are willing to receive cognitive therapy (as either a switch or augmentation treatment) differ from those who are not in terms of baseline clinical and demographic features, symptomatic response to citalopram in initial treatment, or side effect experience with citalopram?

2. Do those who will accept only a switch strategy (three medication treatment options or cognitive therapy) differ from those who will accept only an augmentation strategy (two medication treatment options or cognitive therapy) in terms of the same parameters?

3. Do those who will accept only a medication switch (three medication options) differ from those who will accept only a medication augmentation (two medication options) in terms of the same parameters?

Method

The rationale and design of STAR*D have been detailed elsewhere

(6,

7) . A summary of the methods is presented below.

Study Participants

From July 2001 to April 2004, STAR*D enrolled outpatients 18 to 75 years of age from 18 primary care and 21 psychiatric care practice settings across the United States. All enrollees had previously received a clinical diagnosis of nonpsychotic major depressive disorder, which was verified by a checklist based on DSM-IV criteria. Advertising for participants was proscribed to ensure that recruitment would produce a sample representative of patients seen in typical clinical practice. Written informed consent was obtained at study entry and again at enrollment in the second-step treatments.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

STAR*D used broad inclusion and minimal exclusion criteria

(7) to ensure enrollment of a representative study sample. Inclusion criteria included a score ≥14 on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D)

(9,

10) . Patients with suicidal ideation were eligible if the treating clinicians deemed outpatient treatment to be safe for them. Patients with substance dependence were eligible if inpatient detoxification was not required. Exclusion criteria included a well-documented history of nonresponse to, or clear intolerance (in the current depressive episode) of, any of the treatments in the first two protocol treatment steps; a lifetime history of any bipolar or psychotic disorder; a primary diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive or eating disorder; or the presence of a general medical condition that contraindicated one or more protocol treatments. Women who were breastfeeding, pregnant, or intending to conceive in the 9 months following study entry were excluded, as were participants taking concomitant nonpsychotropic medications that contraindicated one or more protocol treatments and participants receiving targeted psychotherapy aimed at their depression

(6,

7) .

Measures of Level 2 Baseline Characteristics

Baseline measures were collected by clinical research coordinators, by research outcome assessors through telephone interviews and by an interactive voice response system. Clinical research coordinators collected standard sociodemographic information, self-reported psychiatric history (including an assessment of suicidality), medical comorbidity as assessed with the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale

(11,

12), and depressive symptom severity as assessed with the HAM-D, the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Clinician Rating (QIDS-C)

(13 –

15), and the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Clinician Rating

(16 –

18) . The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire

(19) was used to assess for the presence of 11 concurrent psychiatric disorders.

Research outcome assessors administered the HAM-D and the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology. Anxious depression was defined on the basis of the anxiety/somatization factor of the HAM-D

(20), and items from the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology were used to establish the presence or absence of atypical features

(21) . The interactive voice response system was used to administer the self-report version of the QIDS (QIDS-SR)

(13 –

15) .

Treatment With Citalopram (Level 1)

Citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), was used as the first treatment for all participants in Level 1 of STAR*D. The dosage was started at 20 mg/day for the first 4 weeks, raised to 40 mg/day for weeks 5–6, and raised to 60 mg/day for weeks 7–12. The protocol recommended that medication treatment visits be conducted at weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 for all STAR*D medication treatments, although the visit schedule was flexible and extra visits could occur if clinically indicated. If participants had a response (defined as a reduction of ≥50% in baseline QIDS-C score) without remission (defined as a QIDS-C score ≤5) at week 12, they could continue treatment for an additional 2 weeks to determine whether that status was sustained. Symptom severity was assessed at each treatment visit with the QIDS-C and the QIDS-SR. The frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects were monitored with a scale developed for the STAR*D study

(22) .

Moving to Level 2 or to Follow-Up

After Level 1 treatment, participants could decide to move to Level 2 (a randomized clinical trial comparing up to seven different treatments) or to the 12-month naturalistic follow-up phase. This decision was made by clinicians and participants on the basis of clinical judgment informed by side effect status and QIDS-C scores, which were obtained at treatment visits by researchers who did not have any knowledge of the primary research outcome measure (HAM-D score). Participants who did not achieve remission with citalopram or had a clear intolerance to the drug were encouraged to move to Level 2. Those who were in remission were enrolled in the follow-up phase. Those whose symptoms responded to treatment but without remitting were strongly encouraged to proceed to Level 2, although they could elect instead to enter the follow-up phase. Switching to another treatment required neither a tapering of citalopram nor a washout period.

Level 2 Treatments

Level 2 treatments included four switch options (sustained-release bupropion, sertraline, extended-release venlafaxine, and cognitive therapy) and three augmentation options (citalopram plus sustained-release bupropion, buspirone, and cognitive therapy).

Acceptability of Level 2 Treatments

An equipoise-stratified design

(8) was used to approximate typical clinical decision making while retaining randomized comparisons. This design enhanced both study feasibility and generalizability by allowing participants to accept or reject certain treatment strategies, such as by specifying whether either or both the switch and augmentation strategies were acceptable, declining or accepting cognitive therapy within the strategies accepted, and declining all second-step medication changes to guarantee treatment with cognitive therapy either alone or as an augmentation to citalopram. Participants were eligible for inclusion in the instances where multiple treatment strategies were acceptable or a single treatment strategy with multiple treatment options (e.g., medication switch) was acceptable. For example, participants could decline all switch options and be randomly assigned to one of the three available augmentation options. However, participants could not select a specific medication. If participants accepted only one treatment option (e.g., only a switch to cognitive therapy), they exited the study because random assignment was not possible.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses of the acceptability of cognitive therapy included all 1,439 participants who enrolled in Level 2. Analyses of the acceptability of either a switch strategy or an augmentation strategy included 1,273 participants after exclusion of the 166 participants willing to accept both strategies. Analyses of the acceptability of either a medication switch or an augmentation strategy included 1,013 participants after exclusion of the 259 participants willing to accept cognitive therapy as a switch or as an augmentation and the 166 participants willing to accept both an augmentation and a switch strategy.

For each subsample, a variety of sociodemographic and clinical factors were assessed for associations with acceptance of second-step treatment strategies. Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, insurance status, education, income, and number of people in household. Clinical variables included clinical setting (primary care or psychiatric practice), family history of depression or bipolar disorder, history of suicide attempt, atypical depression, anxious depression, age at onset of first major depressive episode, number of major depressive episodes, chronicity of depression, time since onset of first depressive episode, presence of comorbid general medical disorders, presence and number of comorbid psychiatric disorders (obsessive-compulsive, panic, social phobia, posttraumatic stress, alcohol abuse/dependence, drug abuse/dependence, somatoform, and generalized anxiety disorders, hypochondriasis, agoraphobia, and bulimia), and features of Level 1 citalopram treatment (side effect burden, duration of treatment, symptom severity, and percentage change in symptom severity after treatment).

Logistic regression models were used to estimate the association of these factors with willingness to accept cognitive therapy, independent of the effect of regional center, and odds ratios were generated. Logistic regression models were also used to estimate the magnitude of the association of these factors with willingness to accept a treatment switch (versus a treatment augmentation) and willingness to accept a medication switch (versus a medication augmentation), independent of the effects of side effect burden, relative improvement in symptom severity in Level 1 (as defined by the percentage reduction in QIDS-SR score), and regional center, and odds ratios were generated.

For the sake of brevity, we report only those characteristics that were statistically significant (p<0.05) in the adjusted analyses. Descriptive statistics for these characteristics, in the form of means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for discrete variables, are presented separately for each subsample.

Results

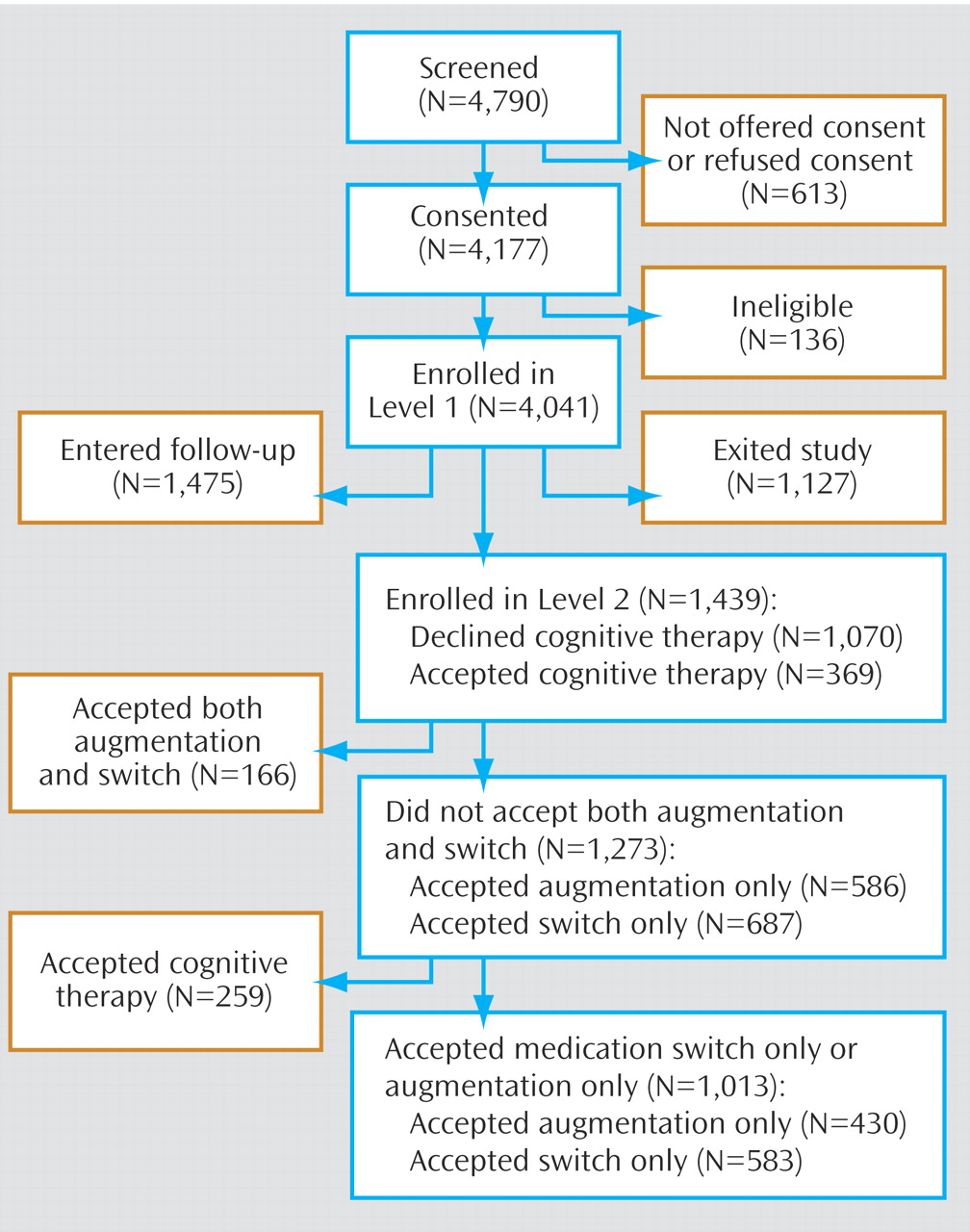

Of the 4,041 depressed outpatients who enrolled in STAR*D, 1,439 enrolled in Level 2 (

Figure 1 ).

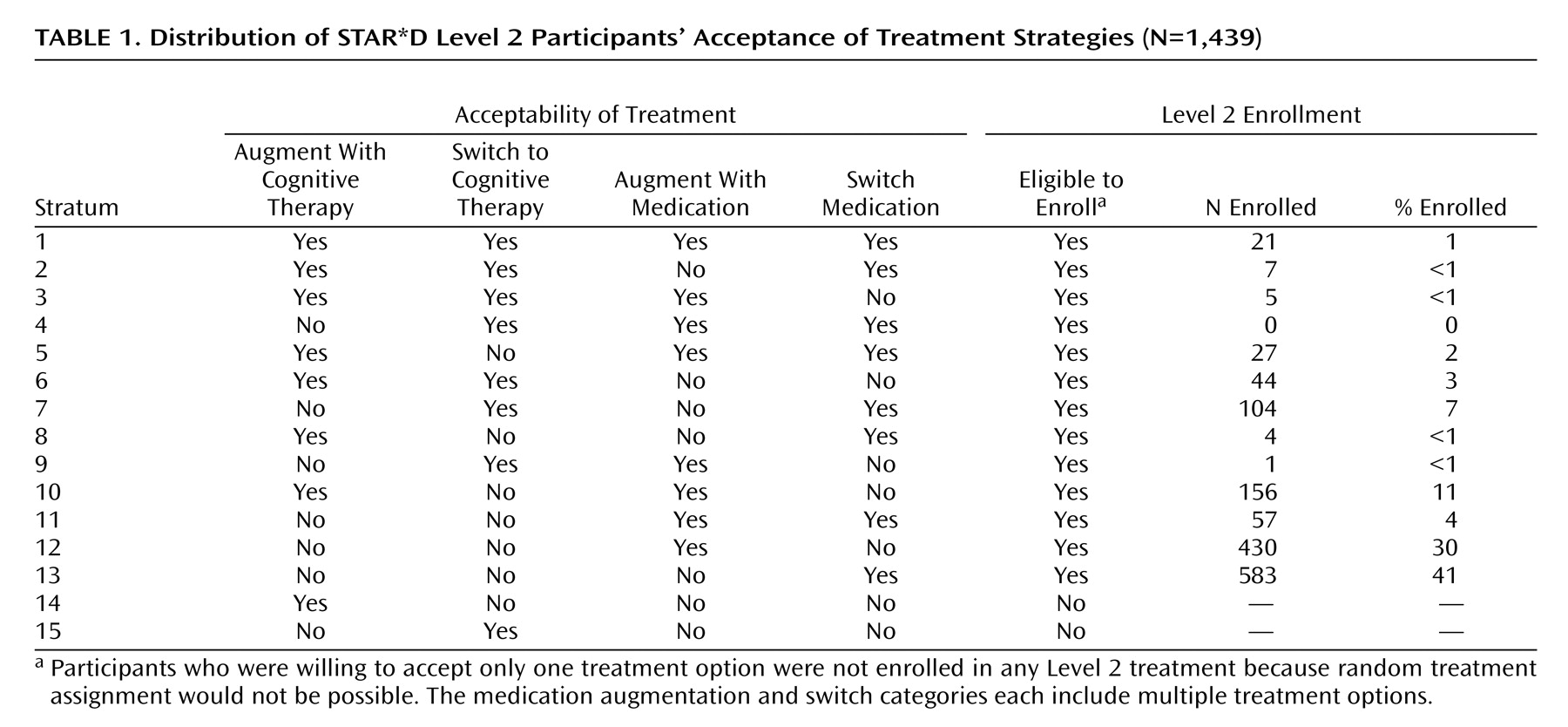

Table 1 summarizes participants’ selections of treatments they would accept. Only 1% of participants (N=21) accepted all seven second-step treatments (stratum 1). Only 3% (N=44) ensured that they would receive cognitive therapy by excluding the medication treatment strategies (stratum 6), and 26% (N=369) were willing (and 74% not willing) to receive cognitive therapy as part of a switch and/or augmentation strategy (strata 1–10). Most participants accepted only a switch strategy (N=687; 48%) (strata 7 and 13) or an augmentation strategy (N=586; 41%) (strata 10 and 12).

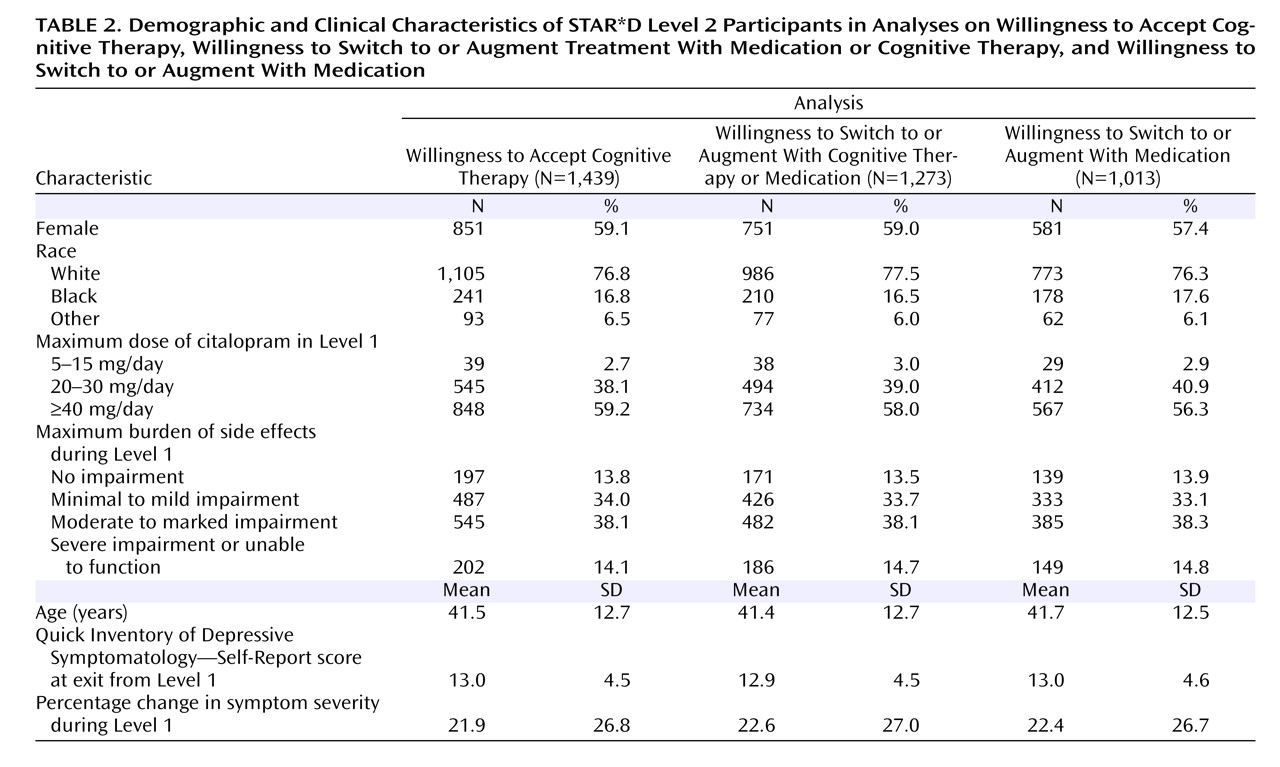

Table 2 summarizes participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics.

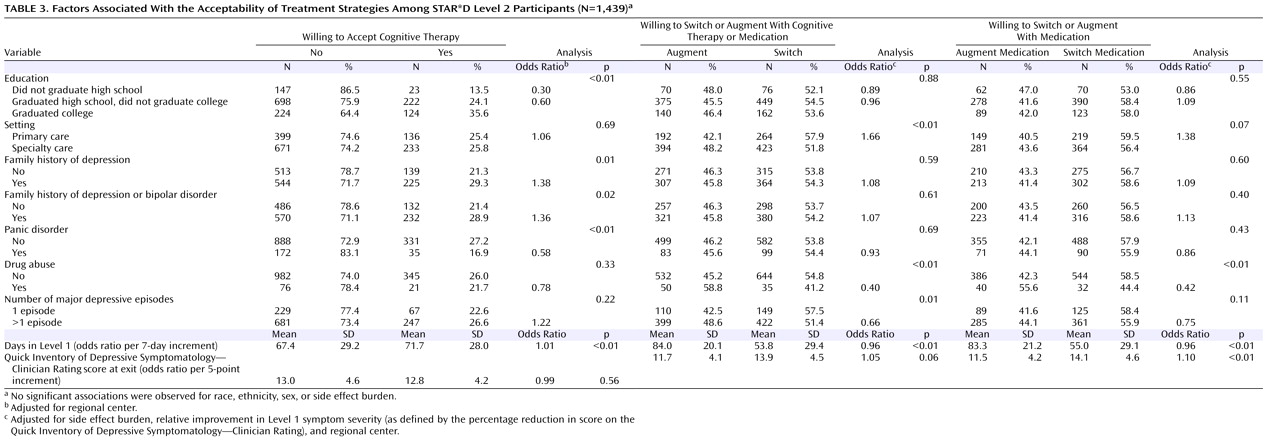

Table 3 presents the analysis of factors associated with the acceptability of treatment strategies.

Willingness to Accept Cognitive Therapy

In this analysis, all Level 2 participants were classified as either willing to accept cognitive therapy (strata 1–10) (N=369) or unwilling (strata 11–13) (N=1,070).

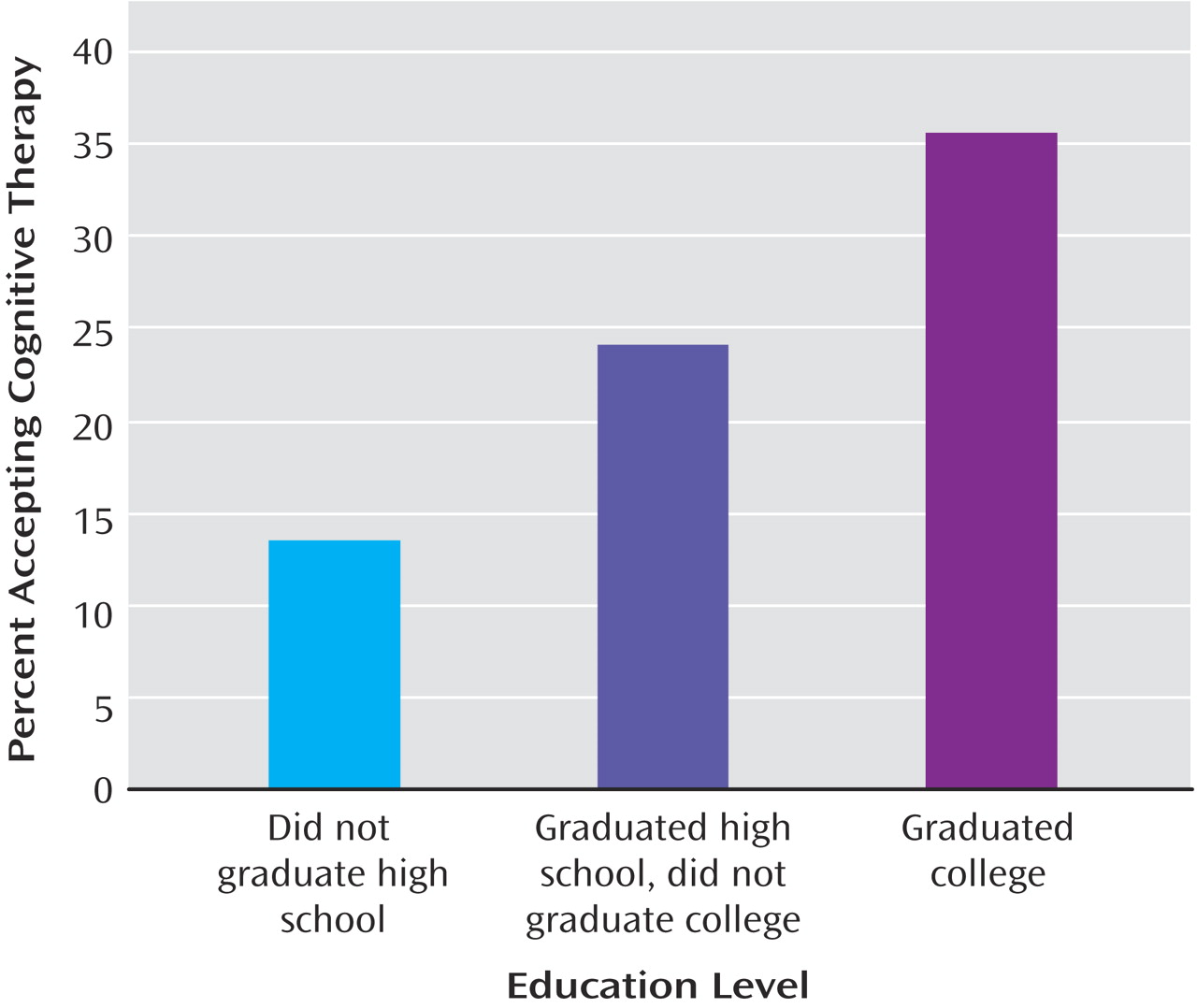

As

Table 3 shows, participants who were significantly more likely to accept cognitive therapy (independent of the effects of regional center) included those with greater education (see

Figure 2 ), a family history of depression, a family history of a depression or bipolar disorder, or a greater amount of time in Level 1 treatment. Participants with panic disorder were significantly less likely to accept cognitive therapy than those without.

Willingness to Accept a Switch Strategy Versus an Augmentation Strategy

Of the 1,439 participants enrolled in Level 2, a total of 1,273 selected either only switch strategies (strata 7 and 13) (N=687) or only augmentation strategies (strata 10 and 12) (N=586). Participants who accepted both switch and augmentation strategies (strata 1–6, 8, 9, and 11) (N=166) were excluded from these analyses. This subsample was similar to the full sample in presenting characteristics (

Table 2 ).

Side effect burden with citalopram at exit from Level 1 treatment (Wald χ 2 =95.1, df=3, p<0.01) and percentage change in depressive symptom severity (Wald χ 2 =70.9, df=1, p<0.01) with citalopram were associated with participants’ acceptance of a switch strategy, independent of the effect of regional center. Participants who experienced greater reductions in symptom severity with citalopram in Level 1 were less likely to accept a switch (odds ratio=0.90 for a 5% increment in symptom severity). The likelihood that participants would accept a switch increased as side effect burden with citalopram at exit from Level 1 increased (minimal or mild side effects versus no side effects, odds ratio=1.51; moderate to marked side effects versus no side effects, odds ratio=3.36; severe side effects to inability to function because of side effects versus no side effects, odds ratio=8.69).

After controlling for the effects of side effect burden, relative change in symptom severity during Level 1, and regional center, participants with concurrent drug abuse were less likely to accept a switch in treatment (odds ratio=0.40, p<0.01), as were those with recurrent major depressive disorder (odds ratio=0.66, p=0.01) or a greater amount of time in Level 1 treatment (odds ratio=0.96, p<0.01). Participants who were treated in a primary care setting were more likely to select switch strategies (odds ratio=1.66, p<0.01) (

Table 3 ).

Willingness to Accept a Medication Switch Versus a Medication Augmentation

Of the 1,273 participants who elected to receive switch or augmentation strategies, 1,013 were willing to receive only a medication switch strategy (stratum 13) (N=583) or only a medication augmentation strategy (stratum 12) (N=430). The 260 participants who were excluded were willing to accept either all augmentation therapies (including cognitive therapy [stratum 10]) (N=156) or all switch therapies (including cognitive therapy [stratum 7]) (N=104) (

Table 2 ).

Significant associations were observed for relative change in symptom severity with citalopram (Wald χ

2 =57.6, df=3, p<0.01) and side effect burden (Wald χ

2 =61.5, df=1, p<0.01), independent of the effect of regional center. Participants who experienced greater reductions in symptom severity with citalopram treatment in Level 1 were less likely to accept a medication switch (odds ratio=0.89 for a 5% decrement in symptom severity) (

Table 3 ). The likelihood that participants would accept a switch increased as side effect burden with citalopram at exit from Level 1 increased (minimal or mild side effects versus no side effects, odds ratio=1.39; moderate to marked side effects versus no side effects, odds ratio=2.84; severe side effects to inability to function because of side effects versus no side effects, odds ratio=6.32).

After controlling for side effect burden, relative change in symptom severity, and regional center, participants with comorbid drug abuse were less likely to accept a medication switch (odds ratio=0.42, p<0.01), as were those with a greater amount of time in Level 1 treatment (odds ratio=0.96, p<0.01) (

Table 3 ).

Discussion

This study is the first to quantify the association of sociodemographic and clinical factors with the acceptability of second-step treatments for major depressive disorder after an unsuccessful first treatment step. The study design allowed participants to exclude treatment strategies while remaining eligible for the study, so long as random assignment to acceptable treatments was possible.

Several key findings emerged. First, few participants were willing to accept all possible second-step treatments. This result highlights the importance of equipoise-stratified randomization and calls into question the generalizability of findings from randomized clinical trials that use a complete randomization design, especially when the randomly assigned treatments involve radically different forms of treatment, such as pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy.

Second, acceptance of cognitive therapy was associated primarily with sociodemographic characteristics (education level and a family history of mood disorder) and was unrelated to the degree of improvement patients experienced with citalopram or whether they were intolerant to the drug. Thus, participants’ acceptance of cognitive therapy was not related to the course of the first treatment step. No association was observed between acceptance of cognitive therapy and insurance availability and type (i.e., private, public, or none). However, programs were reimbursed for the cost of therapy if patients did not have insurance, which to some extent decoupled acceptability and affordability.

Third, only 29% of participants were willing to accept cognitive therapy as a second-step treatment. This proportion was substantially lower than anticipated, and if it is generalizable to settings outside of those of STAR*D, it may suggest a limited potential utility for psychotherapy as a treatment alternative for patients who do not respond to antidepressants. However, the acceptance rate of cognitive therapy may have been diminished by the study design, which required that participants accept medication as a first-step treatment. In another study, Schatzberg and colleagues

(23) found that nearly 90% of patients who initially consented to random assignment to pharmacotherapy or a form of cognitive behavior therapy, either singly or in combination, were willing to switch from pharmacotherapy to psychotherapy. Logistical issues (e.g., off-site location of therapists and, for patients with insurance, responsibility for copayments) also may have made cognitive therapy less attractive than a second course of pharmacotherapy to some participants.

Fourth, the acceptance of a switch strategy versus an augmentation strategy was primarily driven by participants’ experience in the initial treatment. As one might expect, participants who experienced only a modest reduction in depressive symptoms or a greater side effect burden with the initial treatment were more likely to prefer discontinuing that treatment and switching to a new one. Participants in primary care settings were also more likely to prefer a treatment switch, independent of side effect burden and degree of reduction of depressive symptoms. This finding may be attributable to a preference among primary care physicians for avoiding polypharmacy.

Finally, factors associated with preferring a medication switch to a medication augmentation were consistent with those related to preferences for switching or augmenting when cognitive therapy was among the options. This finding can be attributed to the large overlap in the two cohorts. In some instances, the differences in statistical significance can be attributed to a reduction in sample size.

Despite the utility of STAR*D’s innovative study design, several limitations should be noted. Because the design grouped three medication switch options into one strategy and two medication augmentation options into another, the acceptability of individual treatments could not be assessed. The study also did not assess the processes by which consensus was reached on treatment acceptability within the participant-clinician dyad; the specific preferences of participants and clinicians were not recorded—only the resulting consensus preferences.

Future studies with a similar design using SSRIs other than citalopram as the first-step treatment for major depressive disorder may further enhance our understanding of the factors associated with patients’ preferences in selecting second-step treatment strategies. We might also benefit from research on factors associated with patients’ acceptance of individual second-step treatments.