They say a picture is worth a thousand words. In Being There: Medical Student Morgue Volunteers Following 9-11, Dr. Barry Goldstein provides powerful evidence of this. As a visiting professor at New York University Medical School, Dr. Goldstein, physician and photographer, used his insight and skills to record the stories of 16 medical students who volunteered at the morgue immediately following the attacks on September 11, 2001. His photographs and interviews were done 9 months after the events but still convey the depth of impact that this service had on these young medical professionals.

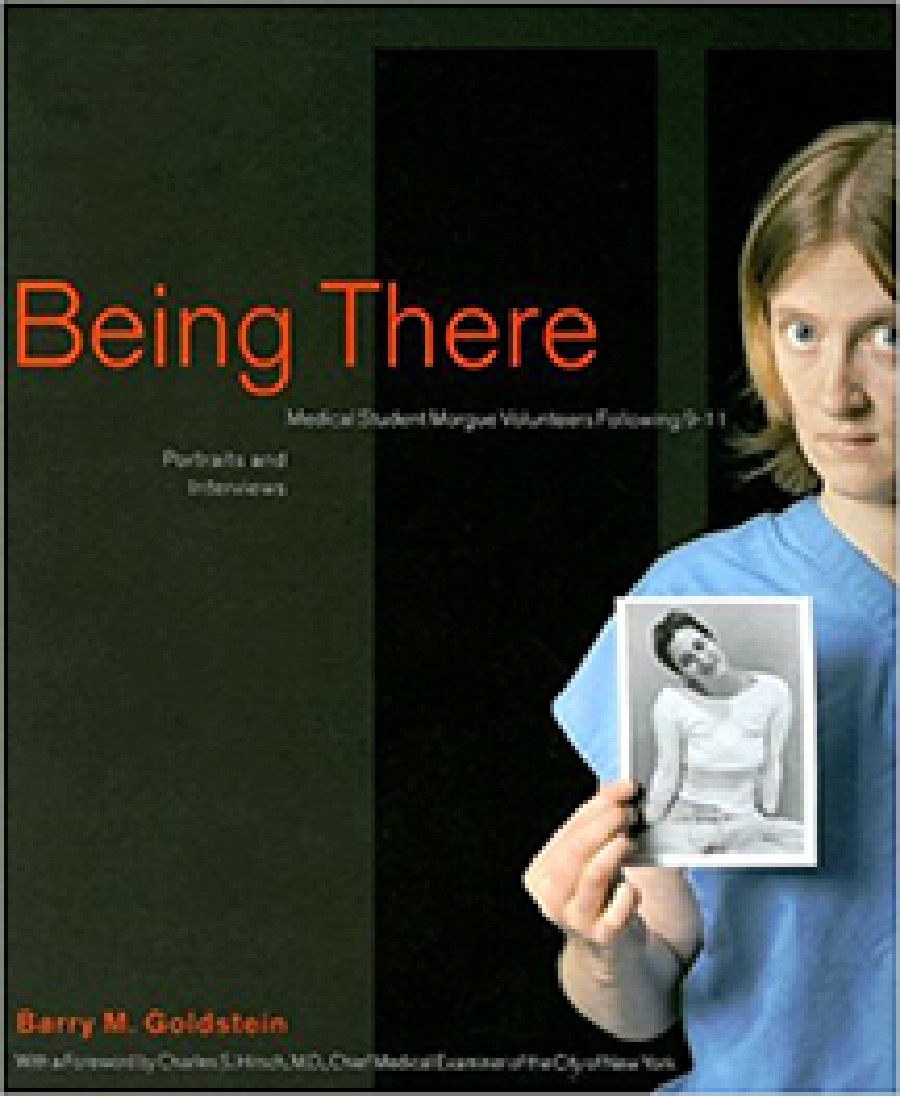

The book provides glimpses of these students’ lives, experiences, and coping mechanisms. Dr. Goldstein photographed them in the scrubs they wore while working at the morgue, with items or people that helped them deal with the strains of the work.

The first theme that arises is the sense of helplessness experienced after the attacks that drove many of the students to find a way to help at the morgue, which had expanded into the street using tents to deal with the sheer volume of work that needed to be done to identify the victims.

The DSM-5 expanded criterion A for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to include “experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s) (e.g., first responders collecting human remains)” (

1). Herein, we find the second theme, finding that many of the students describe not just this type of exposure but symptoms of PTSD, namely nightmares and intrusive images and thoughts related to their work. This is not to say one can diagnose them based on their narrative in the book, but it does show how providing forensic medical services had a lasting impact on these students.

Finally, the way the students found ways to cope with what they were going through gives a glimpse into the other side of the traumatic experience. One student talks about his “rehumanization” through writing (pp. 58–59). This points to the experience of removing oneself from a traumatic situation in order to get through it, a process described by several of the students. How then does one get back in touch with oneself? Each found their own way of processing: talking to friends and family, interpreting their experience through faith, just crying in the days and weeks that followed not just the attacks, but in the months some spent working in the morgue.

As the attacks of September 11, 2001, become part of history, this book reminds us of the humanity of it. A profound and reflective collection of stories and photographs, the one drawback of this book is the abrupt ending. It left this reader with feelings of shock and sadness, appropriate, yet unfulfilling. The last interview ends with a discussion of a loss of faith and conveys a sense of hopelessness. After skillfully weaving in the complex narratives and photographs to recreate a perspective of the fallout from the 9/11 attacks, Dr. Goldstein leaves us questioning what to believe in the face of what happened.