Nearly 20% of patients with psychiatric disorders have a comorbid substance use disorder (

1). Stereotyped beliefs of only oral, intravenous, and intranasal use of substances are antiquated. Creativity and innovation abound in the techniques and routes chosen to abuse substances. Most substances of abuse can be consumed via two or more routes of administration (

2). The acute and chronic physiological effects of substance abuse vary based on the type of substance abused and the route of administration utilized. Each of the various routes of administration carries unique and acute medical risks (

3). Clinicians should be prepared to educate patients about the acute and long-term risks associated with routes of administration.

The objective of the present study was to assess practitioner attitudes and practices with regard to collecting data on the routes of administration of substances of abuse, as well as to provide information on current APA guidelines regarding practitioner evaluation of patients' use of illicit substances.

Method

A survey was distributed via Qualtrics Survey Software (

https://qualtrics.com) to 63 members of the faculty and academic residency program in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine at East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C. The survey was also sent to 13 third-year medical students rotating with the department. The design of the survey was aimed to characterize practices in substance abuse history taking in the clinical setting, specifically relating to inquiry about the routes of administration of substances of abuse. The study was exempt from institutional review board inspection.

In addition to medical students, the targeted participants included therapists, psychologists, residents, fellows, and attending physicians treating both adults and adolescents in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Various demographic characteristics with respect to age and level of expertise were included in the survey. Initial distribution of the survey took place on May 9, 2017, and was available for 1 month, with three weekly reminders. Responses were completely anonymous, with no Internet protocol addresses or identifiers collected. Data were gathered and further analyzed with Qualtrics. The response rate was 54%. All participants answered the same number of questions. Complete confidentiality was maintained in the survey, and the surveyors remained blinded.

Rectal Administration

Literature on substance abuse involving the rectum as a route of administration is sparse. Slang terms for this practice include "boofing" (

4) and, if alcohol is involved, "butt chugging" (

5). Dissolved substances are inserted into the rectum, and fabric or tampons are inserted to prevent leakage (

6). The rich vasculature in the rectum leads to rapid onset of euphoria. There are several acute risk factors associated with "boofing." The substances most commonly used during "boofing" (stimulants and psychoactive synthetic drugs) can be potent vasoconstrictors of rectal and colonic vasculature. Vasoconstriction can trigger mesenteric ischemia. Nontreatment of mesenteric ischemia can lead to tissue necrosis, necessitation of colostomy, or death. Possible mucosal damage caused by "boofing" can increase the risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections. Because the bioavailability of illicit substances in the rectal vasculature is unknown, there is no well-defined dosage to recommend to avoid overdosing (

7). Nontherapeutic placement of substances in the rectum may also cause hematochezia, tenesmus, colonic perforation, and fecal incontinence (

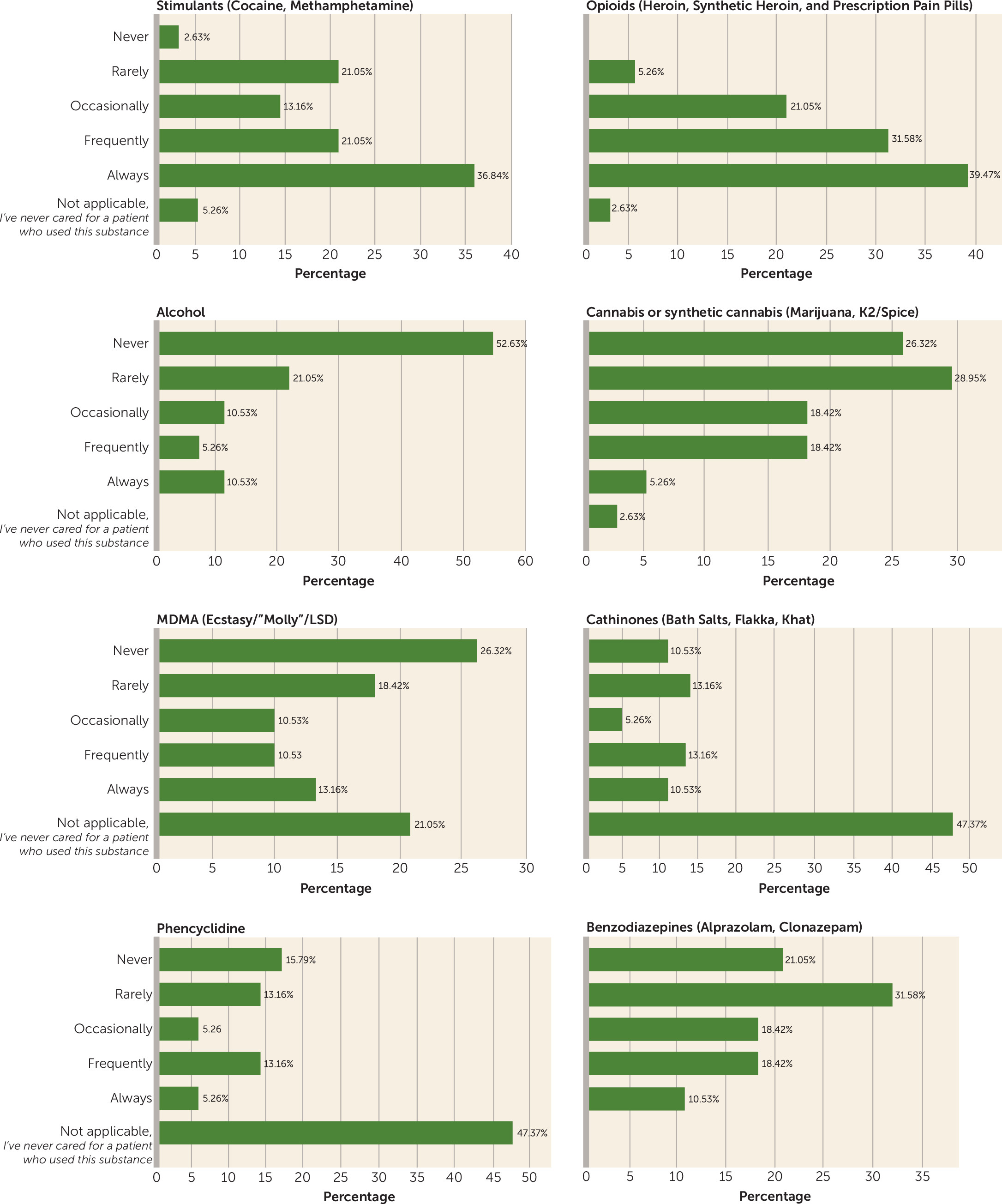

8). For survey results pertaining to practitioner knowledge of substances abused rectally, see

Figure 1.

Skin Popping

Another method used is "skin popping," which involves the user pulling the skin upward then injecting the drug subcutaneously or intradermally, usually in the arms or legs (

9). Water-soluble substances can be injected through skin popping. Common drugs abused using this method are opiates, cocaine, and barbiturates. Individuals who use drugs intravenously often choose this alternative method of administration after their veins become damaged from repeated intravenous drug use (

10). Psychiatrists should caution patients that skin abscesses are a common complication of skin popping. Skin abscesses can result from any combination of factors, including needle-induced local trauma, infectious contaminants, or lack of sterile technique. Abscesses usually contain Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Clostridium botulinum, or tetanus (

11). Early-stage treatment for skin abscesses involves antibiotics. Treatment escalation requires surgical incision and drainage. Untreated abscesses evolve to bacteremia or osteomyelitis (

12).

Insufflation

Prescription-stimulant medication abuse is not limited to the oral route. Insufflation as a route of administration is rising in popularity. Insufflation, colloquially referred to as "snorting," is the act of inhaling either a gas, powder, or vapor into the nostrils (

13). When stimulants are snorted, the vascular-rich areas of the intranasal cavity and pulmonary network become dilated, thus increasing the absorptive surface area and allowing for more rapid entry of the drug into the bloodstream. Potential acute medical complications after insufflating stimulants include local tissue damage to the nostrils, acute hypertensive crisis, myocardial infarction, and ischemic or hemorrhagic cerebrovascular accidents (

14).

Results

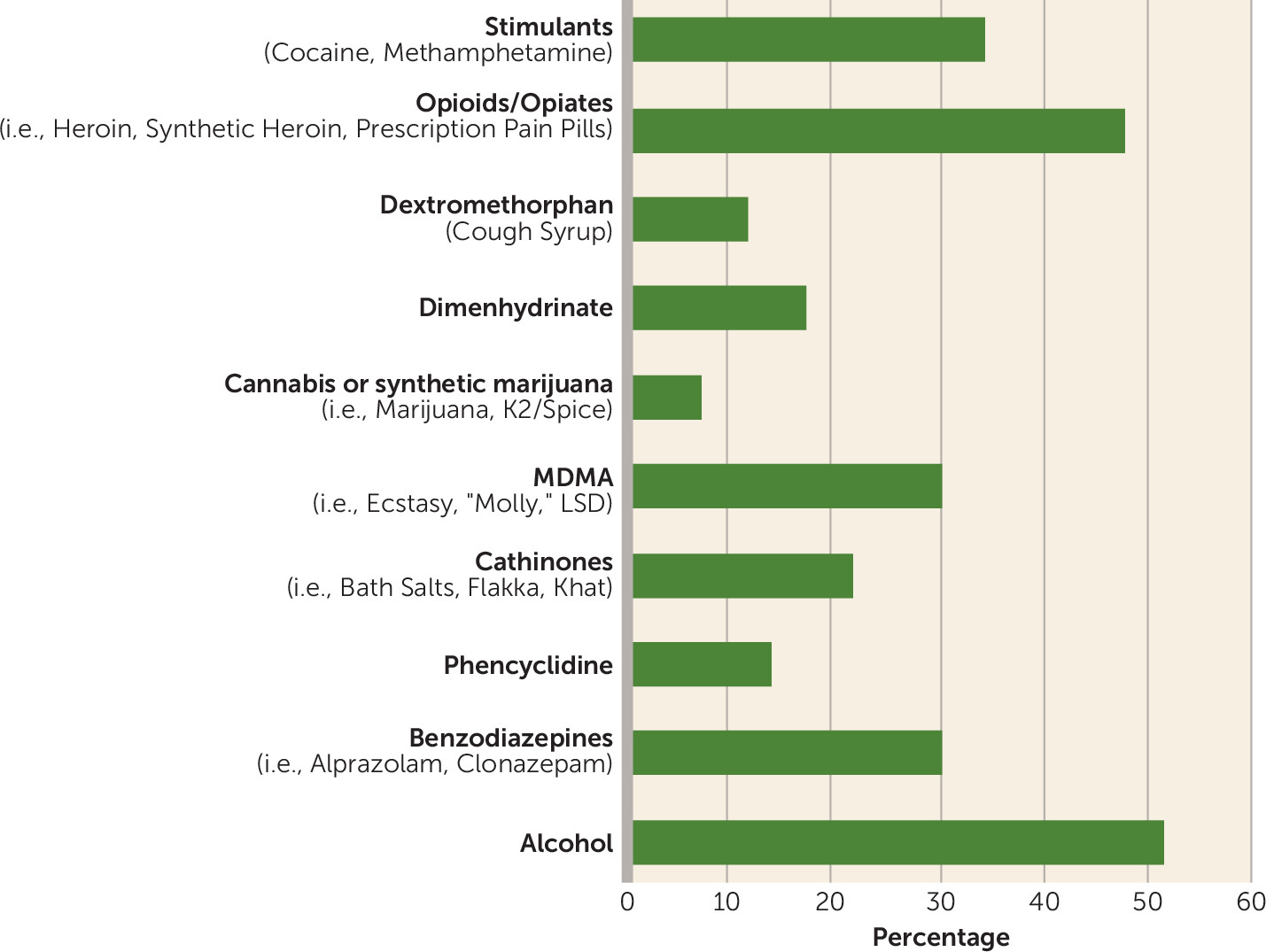

Conducting an assessment of the routes of administration of drugs of abuse allows for practitioners to apply a more effectively tailored treatment plan and better patient education. The interpretation of our results suggests that current substance abuse education within medical training is highly variable and, as it applies to routes of administration, largely insufficient. Stimulants (50%), opioids (75%), and benzodiazepines (37.5%) were the only substance of abuse categories for which more than 25% of respondents reported receiving education (

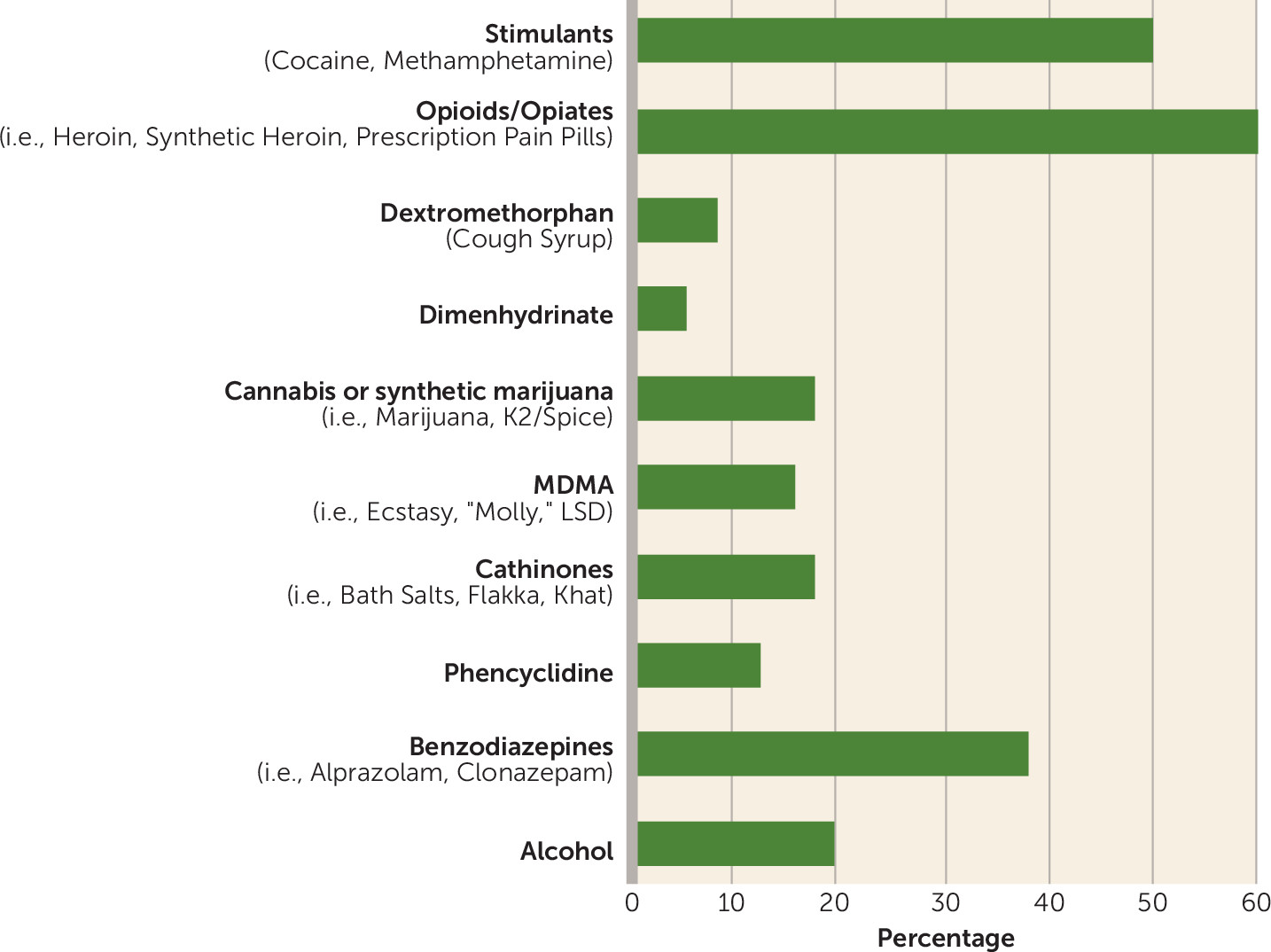

Figure 2). Respondents inquired more about routes of administration for substances they had received education about during some point in their training. Participants frequently or always inquired about the route of administration for two substance classes: stimulants (57%) and opiates (71%) (

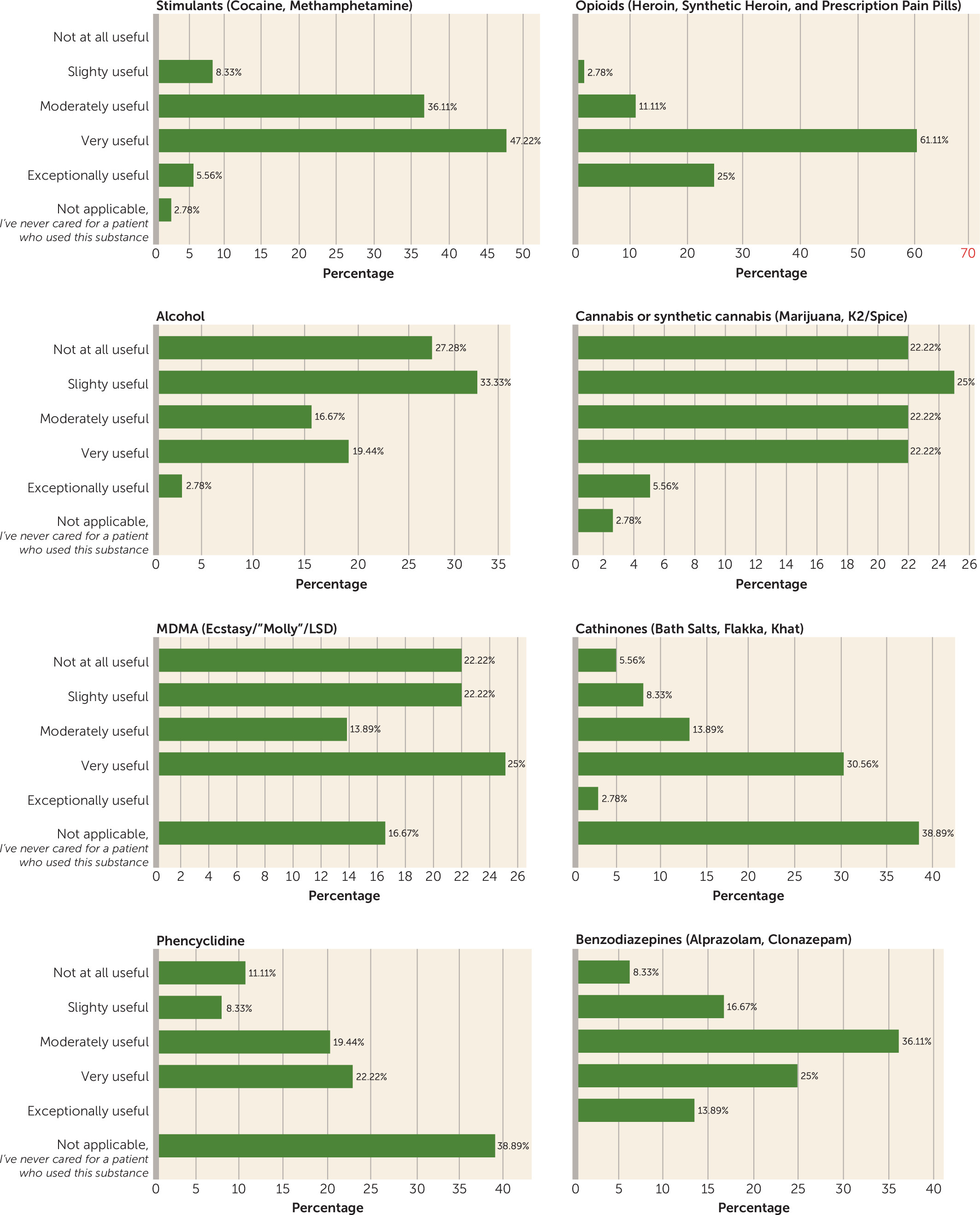

Figure 3). For survey results on practitioner beliefs regarding the importance of screening for the routes of administration of substances of abuse, see

Figure 4.

These results suggest that there would be a potential benefit for a consistent and comprehensive medical curriculum that includes education on the importance of inquiring about the routes of administration of substances of abuse. An established curriculum would enable practitioners to be better equipped to meet the health needs of patients with substance use disorders.

APA Guidelines

Current APA guidelines recommend that the initial psychiatric evaluation include a review of the patient's use of illicit substances, tobacco, and alcohol and misuse of prescription medications. The APA does not delineate which substances for which a route of administration should be investigated but does make clear that the route of administration should be determined for a category of drugs (

15). Treatment planning can be influenced by medical conditions that frequently coincide with substance use. The benefits of conducting a thorough substance-abuse evaluation include lessening the morbidity and mortality associated with drug use (

16).

Discussion

Practitioners should be aware of all routes used for administration of substances of abuse, have a system to gauge which routes of administration patients use, and know the health consequences associated with each route. Stimulants, opiates, synthetic drugs, prescription drugs, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, and phencyclidine are all substances that can be abused by using more than three routes of administration. Although APA guidelines do not delineate which drugs are most important with regard to investigation of routes of administration, we suggest routinely inquiring about the route of administration for patients who abuse any of the aforementioned drugs.

Conclusions

Presently, there is no standardized formulation for conducting the substance abuse portion of a psychiatric evaluation. Furthermore, there is no recommendation for categorizing the severity of abuse using factors that include the route of administration. Future APA guidelines should consider screening questions pertaining to the route of administration of specific illicit substances, as this could potentially affect follow-up and recommended treatment.

Key Points/Clinical Pearls