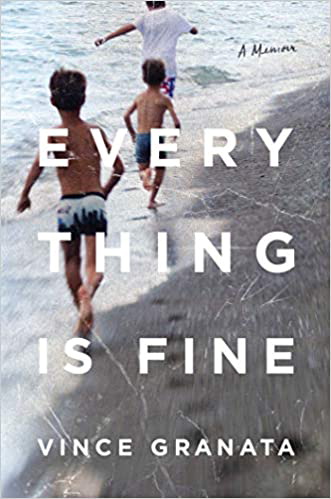

In Everything Is Fine: A Memoir, published in April 2021, Vince Granata opens with a written reenactment of his family’s foundational trauma—his mother’s killing in 2015 at the hands of his brother Tim, who was in the throes of psychosis caused by schizophrenia. Granata then rewinds the story, discussing his earliest memories of Tim in the second chapter, before organizing the story chronologically thereafter. Roughly half the following chapters detail events preceding his mother’s death, such as the onset of his brother’s schizophrenia and its progression, and the other half discuss the subsequent fallout within the family.

Writing with a unique authorial lens, drawing from his background in creative writing and teaching as well as his experiences as a brother and son, Granata utilizes his intimate knowledge of his family to provide an additional layer of emotional depth to an already emotionally fraught narrative. The descriptions are almost theatrical at times, and Granata makes clear that his memoir is not intended to be an objective, detached summary of “events,” a style he notably detests in medical notes, forensic reports, and other records. Instead, in telling his story, Granata writes sections in a stream-of-consciousness format. The resulting accumulation of memories and emotions prevails in key moments, such as a court scene where he watches police footage and describes how Tim “stepped out from behind the dark curtain of [anosognosia],” pleading “destroy me” while sobbing “harder than when I hit him with a plastic brick in second grade, harder than when a sharp reed impaled his palm one Cape Cod summer, harder than on the phone, three years earlier, when he felt alone, like an imposter on his college campus.”

However, this style also limits understanding from other perspectives. Aside from including some passing remarks, Granata sidesteps the perspectives of his family members, with such statements as, “I don’t know if my parents relayed these threats [of suicide being preferable to readmission] to Dr. Robertson,” and “Lizzie and I have never spoken about ... when she found our mother’s body.” This stylistic choice often leaves unanswered questions in the reader’s mind.

Readers may also find themselves looking for more nuance regarding Granata’s own views. For instance, he often references his former naiveté but seldom brings the reader along on the journey of his evolution. Similarly, he mentions several familial idiosyncrasies, but he doesn’t explore their potential relevance. For example, Granata discloses that both his parents are physicians, but he doesn’t explore whether their partial psychiatric knowledge contributed to their belief in “the lie we told each other [that Everything is Fine ].” Moreover, Granata seems to pull punches, avoiding challenges to his personal narrative—most notably in admitting that the sentence “I know that there are ways my mother failed” took him 3 years to write, but then he backtracks and rationalizes, acknowledging that “I’ll never know.... I never asked her.”

Despite these limitations, the memoir delivers an exceptional meditation on grief, as Granata not only laments the death of his mother but also explores the tainting of his childhood memories, the fracturing of his remaining family, and how his imagined future goes unrealized. The book also details numerous expressions of this grief, including depictions of his initial shock, misplaced anger, “inevitable” guilt, struggle to find meaning, and use of alcohol to numb his emotions—vividly displaying many of the Kübler-Ross stages (

1). Granata’s descriptions throughout also exemplify the wavelike nature of grief, which may be elicited equally by major events, like Mother’s Day, and day-to-day reminders, such as a stack of pancakes, a Chopin nocturne, or a Dr. Seuss book (

2).

I would recommend Everything Is Fine to readers whose work involves forensic psychiatry or serious mental illness, because it provides a unique view on topics such as anosognosia, involuntary treatment, and competency restoration from the perspective of a family member of an individual who, as a result of severe mental illness, committed matricide. Additionally, this memoir distinctively details the harmful spillover events of severe mental illness on families, thereby aiding mental health professionals in caring for family members of individuals with mental illness who may experience similarly unspeakable despair and grief.

More generally, I would also recommend that all psychiatric providers consider reading this book, because it provides both a thought-provoking reading experience and exceptional insight into the experiences of our patients’ family members. While reading it, I often found myself frustrated at the seemingly inefficient structure, and I had to restrain myself from reading ahead, past ostensibly unimportant details—the literary equivalent to interrupting an interviewee. In the end, though, these details proved important, providing a level of emotional nuance that deepened understanding in key moments. By the time Granata finds himself worried for the first time about whether his brother will become violent, psychiatrically minded readers may find themselves considering whether witnessing small details and subtle shifts in a person’s behavior, in a more phenomenologically oriented approach, might help them recognize opportunities for intervention. Overall, Everything Is Fine provides a humbling reminder of the limitations of psychiatric evaluations, compared with the lived experiences of patients and family members.