Introduction

The hypothetical case introduces the complex ethical and legal implications of physicians as mandatory reporters when treating patients with mental illness. When a patient with reality challenges (e.g., psychosis, mania, or delirium) endorses having sexual contact with minors, how rooted in reality are these statements? Some providers may prefer erring on the side of caution by automatically reporting these statements to child protective services. However, reporting the patient on the basis of statements that may not be true may cause significant harm by violating the patient’s autonomy and damaging the physician-patient relationship. Further complicating this situation are laws that punish providers who fail to report child abuse. Here, we summarize mandatory reporting laws and provide considerations to help health care providers make informed decisions of whether to report. Finally, we offer policy proposals to address this complex issue.

Mandatory Reporting Laws

All states have mandatory reporting laws, which typically include professions such as physicians. In 45 states, “reasonable” belief of abuse is the standard required to trigger mandatory reporting (

1). State-specific examples are cited below, chosen because we identified pertinent case law from those jurisdictions.

California, for example, defines “reasonable suspicion” as “objectively reasonable for a person to entertain a suspicion, based upon facts that could cause a reasonable person in a like position, drawing, when appropriate, on the person’s training and experience, to suspect child abuse or neglect” (

2). This “does not require certainty,” and there does not need to be a specific medical sign of abuse (

2).

Failure to report child abuse can be punishable under criminal law. In Illinois, violations of the mandatory reporting statute can be punished as a class A misdemeanor (

3), which can include incarceration of up to a year, probation up to 2 years, and a fine up to $2,500 (

4).

On top of criminal liability, there can also be civil liability in the form of a lawsuit (

5). Moreover, failure to report child abuse can have consequences such as suspension of a professional license (

6).

Between the ambiguous language defining reasonable belief and the consequences of failing to report (civil and criminal liability and professional licensure), reporters such as physicians may have a low threshold for reporting to err on the side of safety to protect the investment in their careers.

Assessing Reasonable Belief That Abuse Occurred

That said, courts have provided some guidance in weighing suspicions of abuse. Cases reviewed indicate that reporting need not be automatic (i.e., on the basis of any suspicion) but may depend on professional judgment.

For example, in

Meier v. Salem-Keizer School District, the appellate court upheld a finding that a school counselor did not have to report potential child abuse. The case involved a 17-year-old student with low IQ who was brought before a school counselor after saying she was “molested” by her younger brother. In light of the counselor’s “familiarity with the child, and her experience and training,” the counselor believed that the student did not behave in a way that was expected of a child who had experienced sexual trauma. Further discussion with the child clarified that the contact was likely not sexual but rather “horseplay,” and the counselor did not make a report (

7).

Other cases support the notion that mandatory reporters have some discretion in whether to report. In

Turner v. Nelson, the Kentucky Supreme Court adjudicated the case of a teacher being sued because of alleged sexual abuse between two kindergarten students. The appellate court approvingly cited the lower court’s decision that the reporting law required the teacher to “make reasonable inquiry into the facts, weighing the credibility of each child” and use “her judgment and experience of a teacher of kindergarten level students” to decide whether to report. The court held that the teacher’s decision not to report was “discretionary” (

8).

The Illinois Appellate Court went through an apparent evolution on the issue of mandatory reporting. In 2003, the court wrote that when reporters “suspect or should suspect that a child may be sexually abused, they are divested of any discretion to determine what constitutes ‘reasonable cause to believe’” (

9). However, in 2021, the same court wrote that “a mandated reporter must use his or her discretion to determine whether a report of abuse is credible” (

10).

Conversely, at first glance, California law appears less flexible. An appellate court wrote that the reporting obligation is not on the basis of the “mandated reporter’s personal assessment . . . but on the basis of what a reasonable person would suspect.” (

11) Nonetheless, even this objective standard accounts for “the person’s training and experience, to suspect child abuse or neglect” (

2), building a certain level of subjectivity into the law.

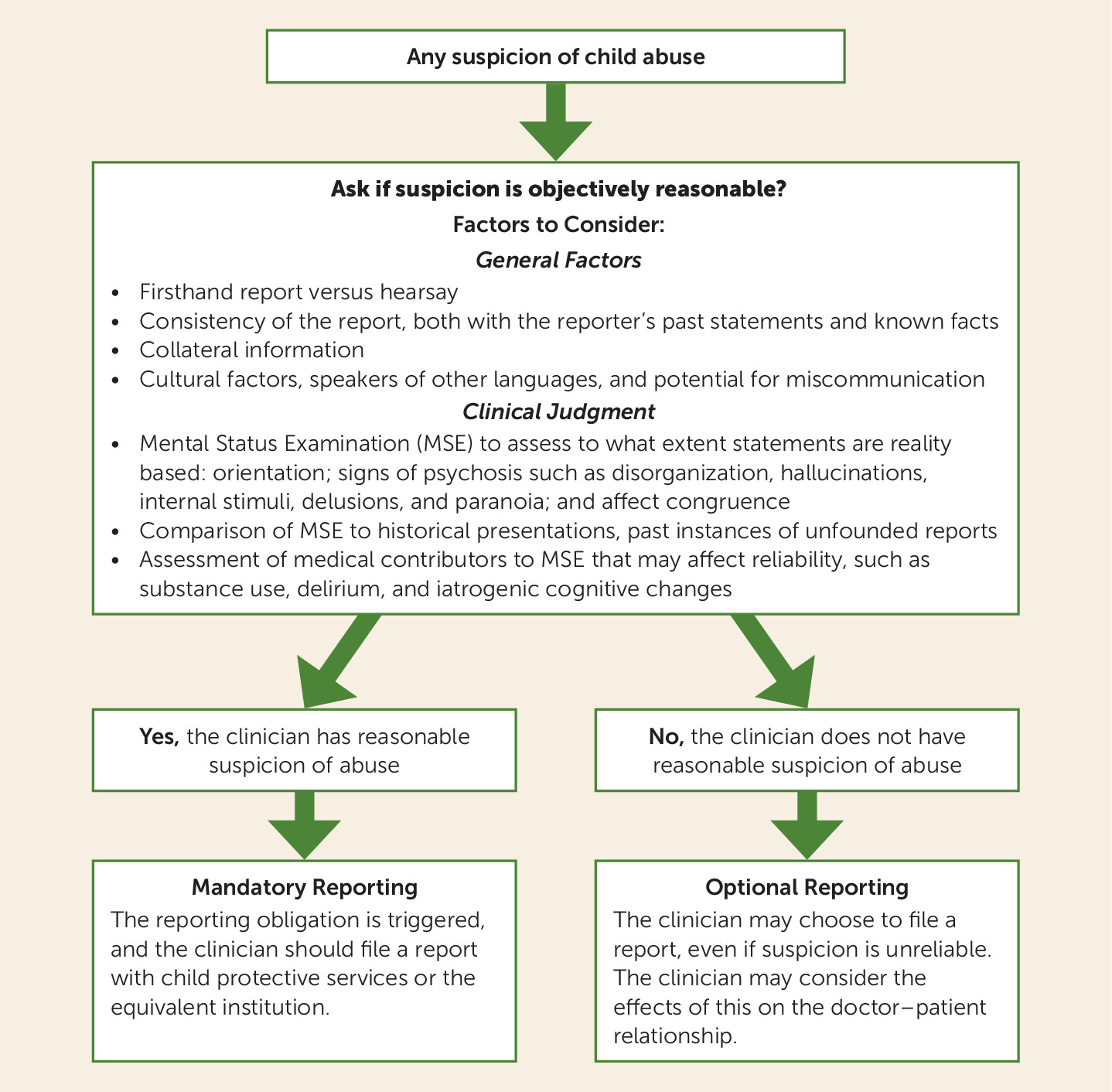

In practice, clinicians should always consult the laws of their jurisdiction when dealing with suspected child abuse. In applying these laws, we offer suggestions to guide clinical judgment, as shown in

Figure 1.

Policy Proposals

We offer several proposals that may help ease the tension between a physician’s duty to a patient, the patient’s autonomy, and the important goal of protecting children. One way to help promote therapeutic rapport with psychiatric patients would be carving out an exemption from mandatory reporting for mental health providers. Indeed, Oregon’s reporting law does this and does not require reporting by a psychiatrist or psychologist (no other professions are mentioned) (

12). Although such an exemption maintains confidentiality in mental health care, it would not cover the above hypothetical case, where a self-incriminating disclosure was made to a surgical team.

Another proposal would analogously draw from criminal law, where self-incriminating statements cannot be used against someone without proper warning under the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution (

13). As seen in the media, police advise suspects of their right to remain silent (

Miranda rights). If mental health providers gave similar warnings, that could benefit patient autonomy by giving advance notice of when confidentiality could be broken and the consequences. Such warnings are especially important in the psychiatric context because the patient’s disclosures and discourse with the provider are part of treatment, and this transparency helps build rapport and trust with the patients.

Although such discussion of confidentiality is common in outpatient mental health practice, medical and surgical teams (such as that in the hypothetical case) would likely not do so. Thus, a policy proposal would be providing confidentiality warnings in all health care encounters.

Darby and Weinstock discussed the ethics of confidentiality warnings in mental health settings, concluding that “fully informed consent on the limits of confidentiality is not in reality advisable.” (

14) They note that doing so would be time consuming and potentially frightening to patients and that most providers could not provide an exhaustive list of circumstances where confidentiality can be broken. In addition to these concerns, requiring more disclosures and paperwork could be an administrative burden to providing care, particularly in a case such as the above hypothetical scenario, where the patient may need care but already harbor paranoia.

A third way to rebalance the equilibrium in favor of patient privacy and the doctor-patient relationship would be to raise the standard of reporting from reasonable suspicion, which is relatively low. A higher standard would be “probable cause,” the next higher level up from reasonable belief in criminal law. This higher standard would trigger reporting only when the evidence is “sufficient to warrant a prudent” person to believe the abuse had happened, as opposed to mere suspicion that something may have happened, which is the current standard (

15).

This would give health care workers more discretion to withhold disclosure, especially in cases similar to our hypothetical scenario where the evidence is ambiguous. Societal interest in child welfare is still protected. At the same time, the patient has greater autonomy to seek confidential care, and the physician has more latitude to provide beneficent care without risking therapeutic rupture. Raising the reporting threshold may be the preferred choice of the three options reported because it finds balance between competing concerns without imposing new burdens on clinicians.