Adoption studies

The three adoption studies of major depression that we are aware of

(55–

57) did not meet our inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis, for the following reasons.

The study by von Knorring et al.

(55) did not find evidence for a genetic influence on major depression. However, the diagnoses of major depression in that study were based on indirect sources (i.e., sick leave registrations and evidence of clinical treatment) that may underestimate the true lifetime prevalence of major depression, as only a subset of those with major depression seek treatment

(58,

59). The odds ratio from this matched design was 0.71 (95% CI=0.16–2.94)

(35, pp. 209–211).

The study by Cadoret et al.

(56) had markedly limited data on biological parents and limited statistical power. This study is widely regarded as not supporting the hypothesis of genetic influences on major depression because the results were nonsignificant when they were analyzed separately by gender. However, the trend-level relationship evident in both genders became significant when the data were combined (χ

2=3.87, df=1, p=0.05; odds ratio=2.54, 95% CI=1.00–6.47, calculations ours).

The large study by Wender et al.

(57) found evidence for a genetic effect on the transmission of major depression (χ

2=4.73, df=1, p=0.03; odds ratio=7.24, 95% CI=1.21–43.20). However, the diagnoses of major depression in that study were based on indirect sources rather than personal interviews.

In summary, two of these three adoption studies provided qualitative evidence consistent with the existence of significant genetic factors in the etiology of major depression.

Twin studies

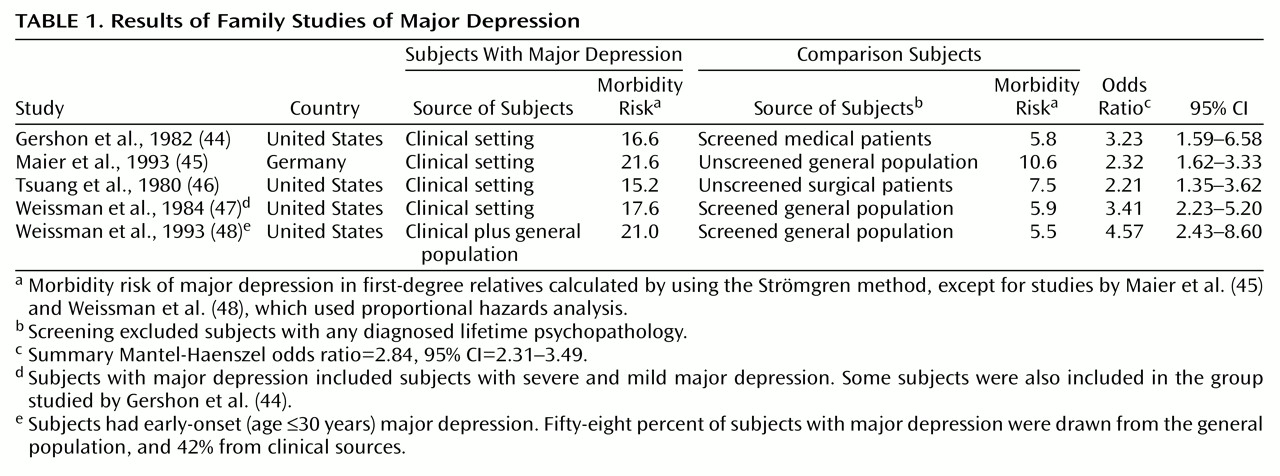

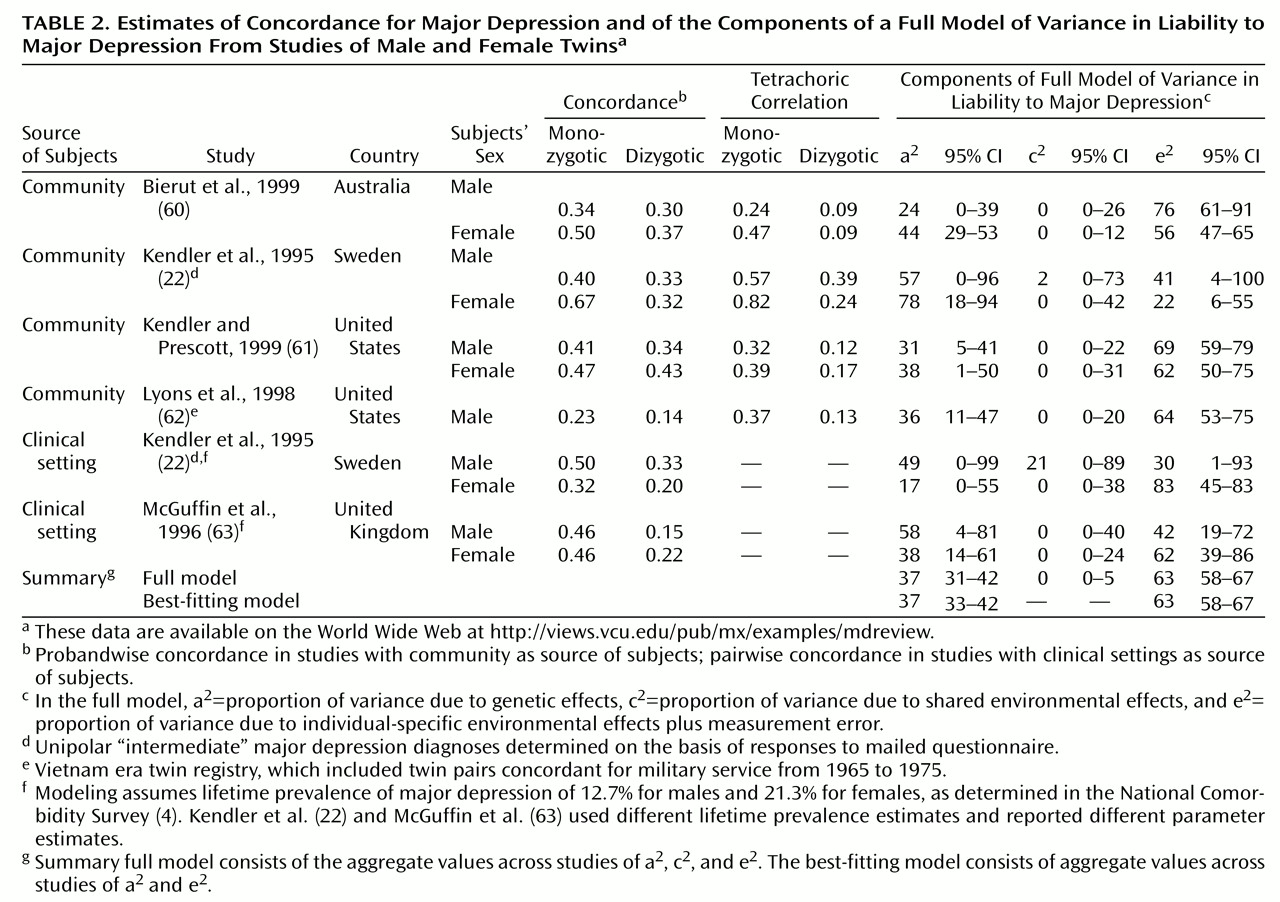

The data from the twin studies of major depression that met our inclusion criteria are summarized in

Table 2. At the time of this writing, the twin data and the principal Mx script are available on the World Wide Web at http://views.vcu.edu/pub/mx/examples/mdreview. More than 21,000 individuals have been included in these studies, and, notably, all of the studies used the DSM-III-R criteria for major depression. Four studies included community samples

(22,

60–

62), and two included clinical samples

(22,

63). The original paper by Kendler and Prescott

(61) has been amended

(64), and the amended rather than the original data were analyzed for this report. Two published reports are not shown in

Table 2. The limited data presented in one of those reports, by Andrews et al.

(65), precluded critical evaluation of the claim that there were no important genetic effects for major depression. In addition, their sample partially overlapped with the larger sample studied by Bierut et al.

(60). We present the most recent data from the longitudinal cohort first reported by Kendler et al.

(3).

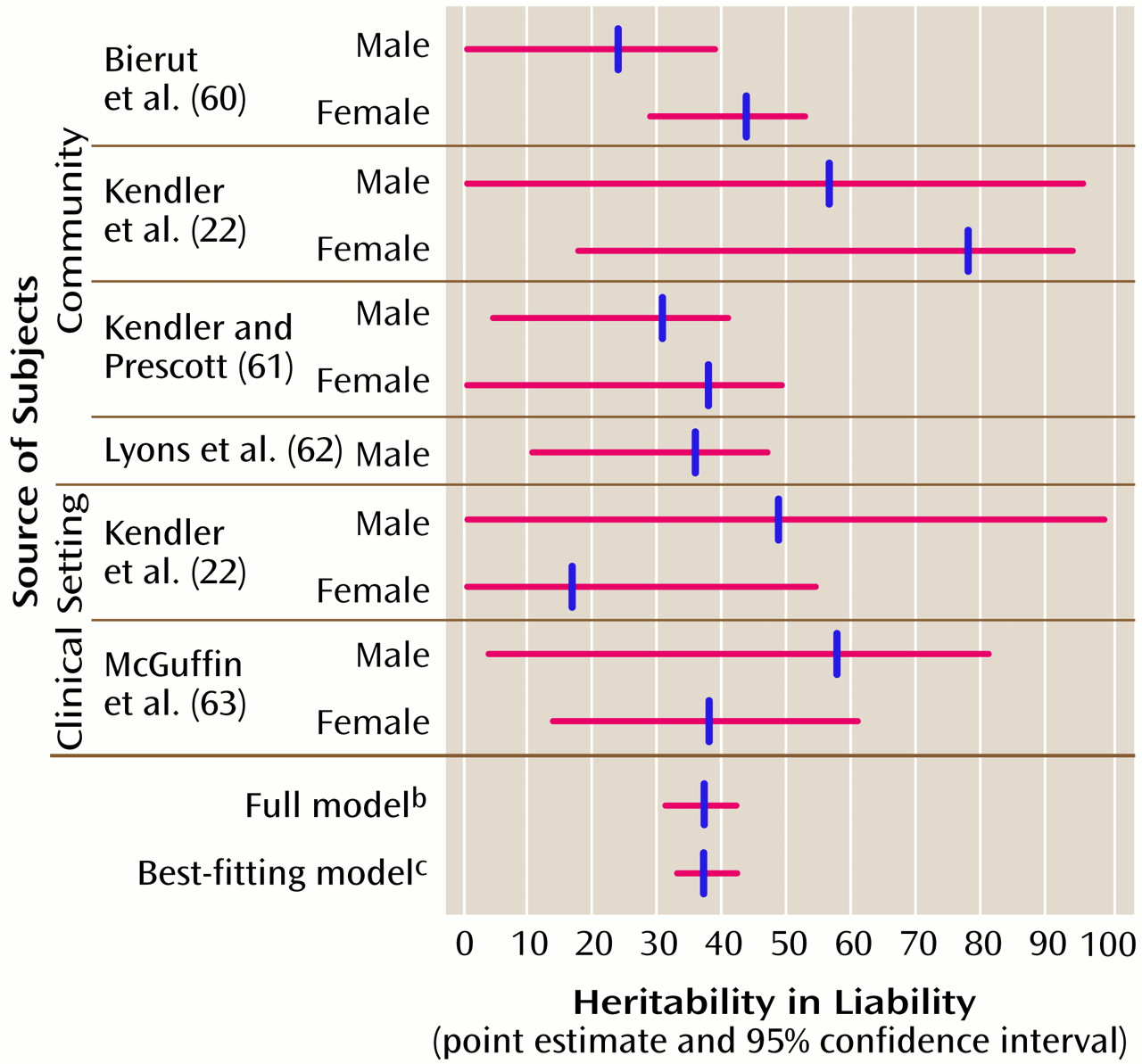

The results from the community and clinical studies summarized in

Table 2 (also depicted in

Figure 1) broadly support five conclusions. First, consistent with theoretical work on the statistical power of the classic twin study for discrete traits like major depression

(66), the 95% CIs for the parameter estimates from these twin studies were fairly broad. One key purpose of a meta-analysis is to combine data across studies in an attempt to narrow the CIs on a parameter and thereby to increase precision. Second, the CIs for a

2 (heritability in liability) did not include 0 for seven of 11 of these studies, suggesting that the aggregate value of a

2 across the studies would be nonzero. Third, the 95% CIs for c

2 (proportion of trait variance due to shared environmental factors) included 0 in all of the twin studies, indicating that environmental influences shared by members of a twin pair are unlikely to have substantial impact on the liability to major depression. Fourth, heritability point estimates from community and clinically ascertained samples were not markedly discrepant. Finally, there were no consistent gender differences across the twin studies.

Before summary estimates of these twin data could be generated, it was necessary to test a number of critical hypotheses and assumptions under which the data might be combined. First, it was necessary to allow the individual studies to have different major depression liability thresholds (i.e., prevalences) because equating the thresholds across studies led to an enormous worsening of the fit of the statistical model (χ

2=739.5, df=10, p≈0). Possible explanations for these differences include cross-cultural differences in major depression prevalence

(67), age cohort effects

(2), and differences in diagnostic approaches. Second, unexpectedly, it was necessary to allow same-sex dizygotic twins to have higher liability thresholds for major depression than same-sex monozygotic twins because equating the thresholds led to a worsening of the fit of the statistical model (χ

2=31.96, df=7, p=0.00004). Slight monozygotic-dizygotic differences have been observed for a number of traits; speculations about these findings generally focus on differential recruitment bias or a subtle protective effect of being a particular type of twin. Third, given the higher prevalence of major depression in women than in men, equating the thresholds for opposite-sex dizygotic pairs led to a considerable further worsening of fit (χ

2=47.13, df=2, p<0.0001). Fourth, when we tested whether the a

2, c

2, and e

2 parameters could be equated versus whether it was necessary for them to be free to vary across studies, we found that it was reasonable to equate the parameters (χ

2=7.86, df=8, p=0.45). This was a critical step in the goal of aggregating data from the published twin studies of major depression. Fifth, we also found that it was reasonable to equate the a

2, c

2, and e

2 parameters for studies from clinical and community sources (χ

2=5.10, df=4, p=0.28). Sixth and finally, it was reasonable to equate the a

2, c

2, and e

2 parameters across gender (χ

2=3.23, df=2, p=0.20).

Although the principal reason for these comparisons was to establish the validity of our meta-analytic procedure, they also allow a substantiative conclusion that is important to our understanding of major depression. Despite the many differences across these twin studies in the prevalence of major depression, ascertainment, methods, ethnicity, and geographic location, the fundamental genetic architecture of major depression appears homogeneous across samples and across gender.

The next step was to generate the 95% CIs of the parameter estimates of the full model (bottom of

Table 2 and

Figure 1). These CIs suggest that the variance in liability to major depression is mostly due to individual-specific environmental effects (58%–67%) and additive genetic effects (31%–42%), with a negligible contribution by environmental effects shared by siblings (0%–5%). It is critical to note that the individual-specific environment includes the effects of measurement error and gene-environment interactions. As this meta-analysis had particular power to detect common environmental effects, it is notable that these effects accounted for a small proportion of variance.

In addition to estimating parameters under a full model, it is useful to investigate whether simpler models offer a more parsimonious explanation of the data

(37). Fitting submodels reduces the number of parameters and leads to narrower CIs. As might be predicted from the summary results in

Table 2, the best-fitting and most parsimonious submodel contained only additive genetic (a

2=37%, 95% CI 33%–42%) and individual-specific environmental effects (e

2=63%, 95% CI=58%–67%).

We investigated the heritability of major depression in community and clinical studies separately because of suggestions that clinically ascertained major depression might be “more genetic.” Estimates of heritability were similar in subjects ascertained from community (a2=37%, 95% CI=28%–42%) and clinical (a2=43%, 95% CI=21%–58%) sources.

Assumptions

There are several potential threats to the interpretation of these studies. First, the critical equal-environment assumption posits that monozygotic and dizygotic twins are equally correlated in their exposure to environmental events of etiologic relevance to major depression. If this were not true, the greater similarity between monozygotic versus dizygotic twins for major depression could result from environmental and not genetic factors. The equal-environment assumption has been examined repeatedly, and there is considerable evidence supporting its validity for major depression

(73,

74). Second, conclusions about major depression from twins may not generalize to singletons if there are protective or risk factors specifically associated with twins. Moreover, twins are distinctive from singletons in a number of potentially important ways

(75); however, the incidence of treated major depression is similar in singletons, monozygotic twins, and dizygotic twins (see reference

76 for review), as are the mean levels of current depressive symptoms

(77).

Finally, some unknown or poorly measured bias may be responsible for the results from twin studies. Estimates of heritability in liability from an alternative design can provide an important cross-check of this possibility. We computed tetrachoric correlations from the results of the controlled family studies of major depression in

Table 1 (38). If a set of fairly restrictive assumptions are met, these tetrachoric correlations multiplied by 2 estimate heritability in liability to major depression

(78). These assumptions are distinct from those of twin studies’ design, and convergent results from different methodological approaches suggest that the assumptions of both methods are problematic or, more parsimoniously, that the results reflect the fundamental nature of major depression. From the family studies summarized in

Table 1, the weighted mean heritability in liability to major depression was 58% (95% CI=42%–74%). Given that probands in all family studies were clinically ascertained, this result is in reasonable agreement with the heritability in liability from clinically ascertained twin studies (a

2=43%, 95% CI=21%–58%).

Without recourse to a more formal experimental design, it is not possible to prove that the results from twin studies are uncontaminated by all conceivable biases and violations of critical assumptions. However, given the available data, there is no reason at present to question the validity of the conclusions about major depression from twin studies.