A call to focus on health-related quality of life in the assessment and management of geriatric psychiatric syndromes in the oldest old is unfortunately necessary. In a hurried clinical world characterized by managed care and fragmented delivery of health services, psychiatrists have withdrawn in part from such practice. For example, in four well-known geriatric psychiatry textbooks published in the United States

(47–

50) (one co-edited by me), only one chapter appears on comprehensive assessment as a strategy for patient care, and no studies are cited that report the efficacy of comprehensive assessment compared with usual assessment. (Prominent chapters on comprehensive geriatric assessment in textbooks of geriatric medicine are replete with recommendations based on empirical studies.)

The syndrome of depression is useful as an example of this approach. Many other syndromes could just as easily be used as examples, such as late-onset schizophrenia with suspiciousness and agitation, memory loss secondary to Alzheimer’s disease, and delirium. I have chosen to focus on depression as an example because of the frequency of the problem, the tendency to treat the problem in the oldest old with medications alone, and the potential for reversing the downward spiral to frailty with appropriate treatment.

Screening for Depression in the Oldest Old

Depressive symptoms are more frequent among the oldest old than in the young old living in the community (over 20% compared with less than 10%), but the higher frequency is explained completely by factors associated with aging, such as a higher proportion of women, more physical disability, more cognitive impairment, and lower socioeconomic status

(51). When these factors are controlled for, there is no relationship between depressive symptoms and age

(52). The rate of major depression in the oldest old is lower than for persons in midlife but may be somewhat higher than for the young old, usually estimated at 2%–5%. (Good estimates from community samples are difficult to obtain because the oldest old are underrepresented in these samples [

52,

53].) The 1-year incidence of clinically significant depressive symptoms is high in the oldest old, reaching 13% in those 85 years old or older; the incidence of major depression is around 1.5%, similar to the rate in younger age groups

(54–

56).

Depression has been associated with disability among the oldest old in a number of studies

(32,

57,

58), illustrating the link between depression and frailty. This association is not limited to major depression alone but to a range of depressive symptoms. Therefore, most people with clinically significant depressive symptoms among the oldest old do not meet criteria for a diagnosis of major depression but experience comorbid physical and/or cognitive impairment and are at risk for a decline in functional status.

Screening for depression in hospital settings and primary care practices as well as in institutions is the critical first step in comprehensive geriatric assessment. Among the self-administered screening instruments available, the Geriatric Depression Scale

(59,

60) and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

(61) are the most frequently used. If the patient cannot participate in a self-report assessment, interviewer-rated scales, such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

(62), can be administered by the nurse practitioner/physician assistant trained in its use. Screening, however, is not directed to making a diagnosis of major depression but, rather, to documenting moderate to severe symptoms of depression regardless of the cause.

Comprehensive Assessment of Depression

If the patient screens positive for moderate to severe depressive symptoms, comprehensive assessment should be undertaken in most cases with the oldest old. Many will view this recommendation as excessive, especially in the era of managed care and managed Medicare. Nevertheless, effectiveness as well as cost effectiveness should be paramount if we are to advance our care of the oldest old and reduce the risk of frailty and failure to thrive. Comprehensive assessment is time intensive but not procedure intensive. The assessment should, if possible, take place in a setting devoted to such assessments—such as a geriatric psychiatry or geriatric medicine clinic. For the remainder of this article, I will describe an approach to assessment management in a geriatric psychiatric clinic staffed by a psychiatrist and nurse practitioner/physician assistant with ready access to a geriatrician and social worker (

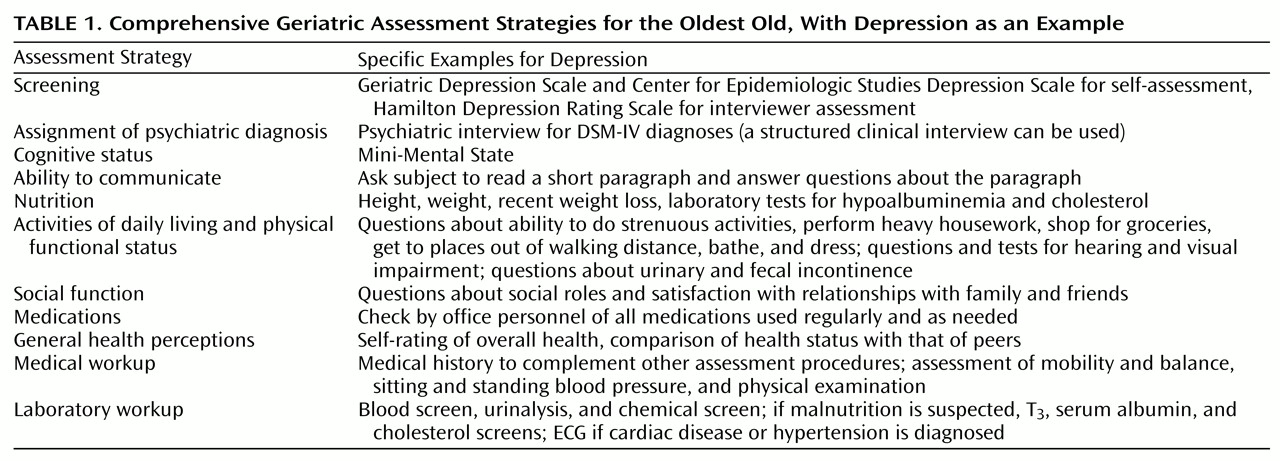

Table 1).

Once the medical and psychiatric histories are obtained, the focus of the assessment should be on health-related quality of life, and much of the assessment can be done by the nurse practitioner/physician assistant. A number of standardized scales are available to assess functional status from self-report (and reports from family members)

(63–

65). The use of standardized assessment tools provides the metrics for monitoring the progress of therapeutic intervention. Some examples will suffice. The nurse practitioner/physician assistant can assess the severity of depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment using standard screening scales

(9,

62). The patient’s ability to communicate should be documented

(66). Physical function can be assessed directly by asking the patient to stand and sit, reach above her or his head, walk across the room, perform fine motor movements such as writing a sentence, etc. The activity should be timed, and the elder’s ability to perform the activity should be determined. The patient can also be asked about his or her ability to perform routine activities of daily living

(43) (

Table 1).

Social function can be assessed by determining the limitations in usual roles and satisfaction with the support network

(8,

11). The perception by the elder of poor social support has been found to be a powerful predictor of poor health and mental health outcomes

(67). General health perceptions are also central to the assessment of health-related quality of life. The perception of poor physical health, even when objective measures of health are controlled for, is a strong predictor of poor health and mental health outcomes

(68).

Following a physical examination, the psychiatrist usually determines that a blood screen and chemical screen will be sufficient laboratory examination. Brain imaging and psychological testing are rarely necessary during the initial comprehensive geriatric assessment of the acutely depressed elder, but they should be ordered if specifically indicated. Findings from such assessments will alter the approach to management. For example, if the depressive symptoms are complicated by memory loss and hypertension (suggestive of vascular dementia), then magnetic resonance imaging is indicated. During the midst of a moderate to severe depression, psychological testing is rarely indicated. In other words, a comprehensive assessment that focuses on health-related quality of life is not procedure intensive; therefore, costs primarily reflect time spent with the elder and his or her family.

Management of Depression in the Oldest Old

Therapy must proceed across multiple domains simultaneously. Management of the depressed oldest old frequently begins with securing the social support necessary to maintain the elder in the community. Referral to a social worker, optimally one who works closely with the clinic, is not as critical for the depressed patient as it is for the patient with memory loss. Nevertheless, short-term caretaking may not be easily arranged during the acute stage of the depression, and the social worker can inform and connect the family with short-term services. Not infrequently, however, depression is in part a symptom of frailty that has gone undetected and untreated. In such cases, families almost always will require outside services over a longer period of time if the elder is to remain in the home (most elders and their families desire initially to reestablish independent living in the home by a transition through in-home care). Managing in-home care is difficult at best for families, even those families with the financial resources to purchase such care. The social worker can provide a much-needed reality check for patients and their families so that the services needed by the depressed elder are implemented and continue without interruption.

The treatment of depression in the oldest old is targeted at improving health-related quality of life in which remission of depressive symptoms is key but not sufficient. Medications are a central component of symptom remission. The new-generation antidepressants, especially the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have greatly improved the safety of antidepressant therapy in the oldest old. The advantage may be more apparent than real, however. For example, in a large study of nursing home residents, there was little difference in rate of falls between those treated with tricyclic antidepressants and those treated with SSRIs

(69). Although it is not clear that efficacy is improved, the new-generation medications are more likely to be taken for sufficient duration and in adequate doses.

Overall efficacy of antidepressant therapy in the oldest old appears to be similar to that of the young old, but there are few good studies of the oldest old in terms of treatment response. In a recent article

(70), short-term response to a combination of nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy was good, but the oldest old had more recurrences during the first year of maintenance therapy than the young old. Comorbid illness and other factors that are known to decrease treatment effectiveness, rather than age, probably account for most age differences in treatment response. For example, people with a frontal lobe syndrome, more frequent in the oldest old but not inevitable, respond less well to antidepressant therapy

(71).

Antidepressant therapy should usually be started at a dose about one-half that given to persons in midlife, e.g., fluoxetine 10 mg/day; paroxetine 10 mg/day; sertraline 25 mg/day; nefazodone 100 mg/day; and citalopram 10 mg/day. Ultimate doses will range widely, even in the oldest old. There are few studies that provide clear dose recommendations for the elderly, but the injunction to “begin low and increase slowly” is well taken.

The adverse side effects that are most disturbing to patients throughout the life cycle are the ones most disturbing to the oldest old—agitation, sleep disturbance, sedation, loss of appetite, nausea, and occasional anticholinergic effects. These side effects are more frequent in the oldest old than the young old, yet they remain relatively infrequent (exact comparisons were not found in the literature). Some side effects that are less frequent at younger ages emerge as major concerns with the oldest old. Hyponatremia may occur in 25% of elderly subjects taking SSRIs

(72). The cause may be the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

(73).

Psychotherapy with the oldest old/frail elderly has been investigated even less than antidepressant therapy and not usually by psychiatrists. One group

(74) investigated interpersonal counseling with a group of medically ill depressed elderly patients and demonstrated improvement according to Geriatric Depression Scale scores compared with a control group. The treatment effect did not improve physical or social functioning, however. In another study

(75), cognitive behavior therapy was found to reduce depressive symptoms but not to improve function in a group of hospitalized stroke patients. Despite the value of interpersonal therapy along with antidepressant therapy in the young old

(2), there is little evidence that psychotherapy is of value for improving function in the oldest old, even though mood did improve in the few controlled trials published.

Reports of behavioral interventions focused on improving social interactions and functional status in the frail elderly are rare, yet behavioral interventions should prove the most important adjunct to pharmacological treatment of depression in the frail elderly. Behavioral interventions range from prescribing regular group activities, physical exercise (such as walking), and training for increased independent function (physical and occupational therapists are most valuable for such training). In actuality, reports of comprehensive interventions, mostly from countries other than the United States, by either institution-based or community-based psychogeriatric teams, usually involve combinations of drug therapy, supportive psychotherapy, work with the families of the depressed elders, and a healthy dose of behaviorally oriented interventions.

Although few in number, studies of comprehensive interventions have demonstrated their value. In a meta-analysis of 14 studies of the effectiveness of outreach teams to depressed elderly in the community

(76), the efficacy was comparable to that found in younger adults, but the dropout rates were high. In another study

(77), home care by an interdisciplinary team for depressed and frail elders led to improvement in 58% of the group treated by the interdisciplinary team compared with 25% in a control group. These studies are preliminary and all too few. The yield in terms of reducing the downward spiral of frailty by such a comprehensive approach to the treatment of the depressed oldest old could be enormous, not only in relieving suffering but also in ultimately reducing health care costs.