A problematic characteristic of unipolar major depressive disorder is the tendency for major depressive episodes to recur and the course to become chronic. Residual depression during recovery from major depressive episodes has been associated with a significantly more frequent relapse of depression

(1). We recently reported that patients with residual subthreshold depressive symptoms during recovery relapsed more than five times faster to depressive episodes than patients with asymptomatic recovery (median weeks well=33 versus 184, respectively)

(2). This study was designed to extend this finding by investigating the long-term course associated with complete versus incomplete recovery from a first lifetime major depressive episode.

Method

The patients studied were enrolled in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression (Collaborative Depression Study), an ongoing, prospective, naturalistic longitudinal investigation of mood disorders in which treatment was recorded but not controlled

(3). Of 431 patients with unipolar major depression in the Collaborative Depression Study, 122 were experiencing their first lifetime major depressive episode without ongoing dysthymia (“double depression”), with no evidence at intake or follow-up of bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophrenia. Patients were diagnosed by means of the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC), based on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS)

(4). Subjects were white, spoke English, had an IQ greater than 70, and had no evidence of organic mental disorder or terminal medical illness.

Trained raters interviewed the patients every 6 months for the first 5 years and annually thereafter, using variations of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation instrument

(5), to obtain weekly symptom severity ratings for each mental disorder covered by the RDC.

The RDC defines recovery from a major depressive episode as 8 consecutive weeks with either full asymptomatic recovery or with one or more depressive symptoms beneath the diagnostic threshold for major depressive episode, minor depression, or dysthymia. Of 122 patients with unipolar disorder entering the Collaborative Depression Study during their first lifetime major depressive episode, 26 had residual subthreshold depressive symptoms throughout their first well interval. These were contrasted with 70 patients who achieved symptom-free recovery for 80% or more of the weeks during the well interval.

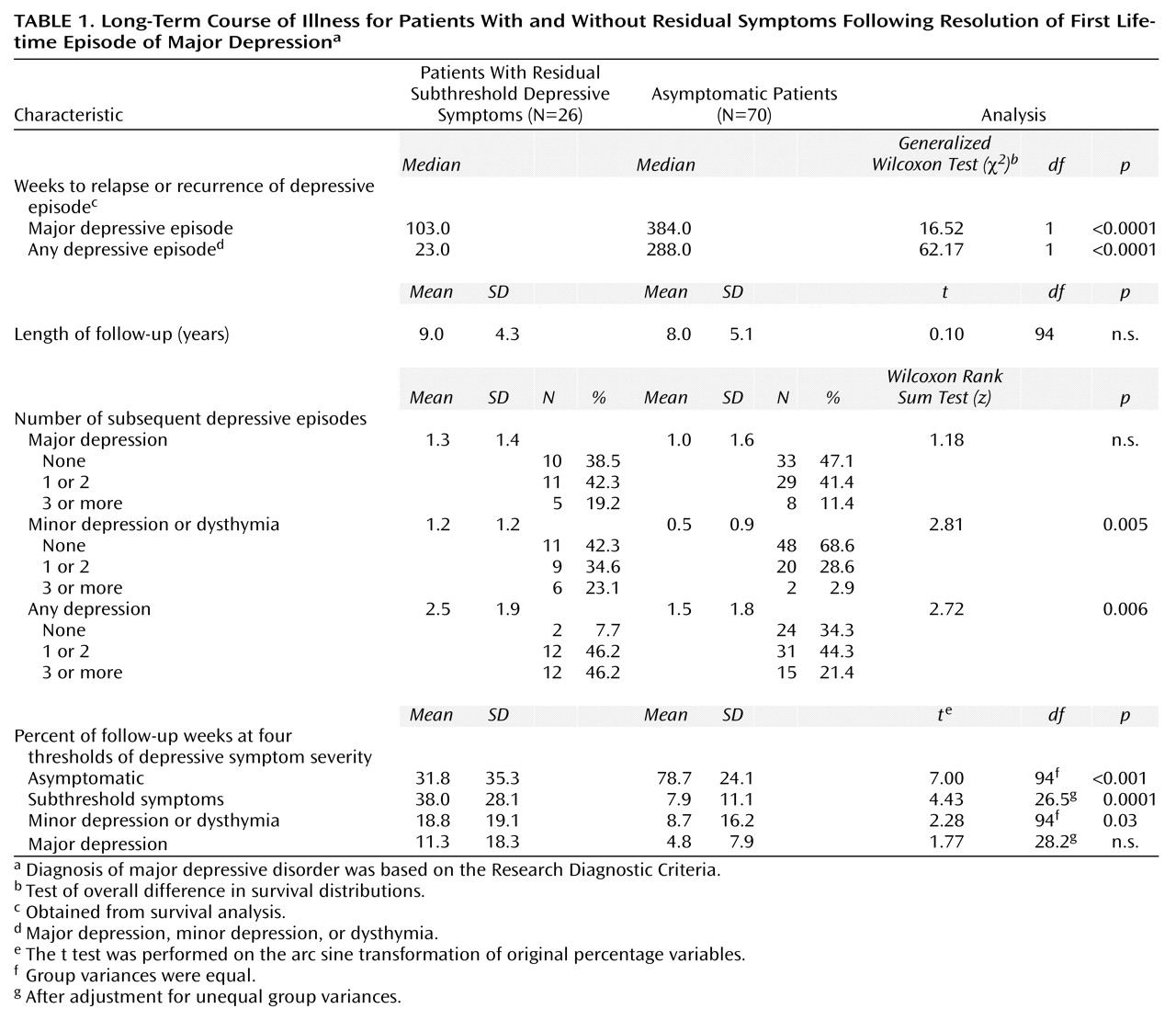

After recovery from the major depressive episode at intake, patients were followed an average of 490.2 weeks (SD=240.8, range=20–780), or 9.4 years. The two recovery groups were compared on demographic and clinical characteristics and long-term outcome. A two-tailed alpha of p=0.05 was used to determine significance. Key results are contained in

Table 1.

Results

The two recovery groups were not significantly different regarding age, sex, educational status, marital status, age at first lifetime major depressive episode, extracted score on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, endogenous depression rating, duration of major depressive episode at intake, worst global assessment of severity score (Global Assessment Scale)

(6) during the major depressive episode at intake, or mean length of follow-up. Significantly more subjects in the recovery group with subthreshold depressive symptoms than in the asymptomatic group were inpatients at intake (84.6% versus 57.1%, respectively) (χ

2=6.26, df=1, p=0.01), but this did not account for difference in outcomes. Of 13 SADS item scores, only the score for suicidal ideation and behavior was significantly higher for the recovery group with residual subthreshold depressive symptoms than for the asymptomatic group (mean=7.2, SD=5.6, versus mean=5.0, SD=4.2, respectively) (z=2.09, p=0.04, Wilcoxon rank sum test). The recovery groups were not significantly different in the prevalence of 12 comorbid mental and/or substance abuse disorders before intake, at intake, or during the first well interval. They also did not differ on mean composite antidepressant treatment scores

(7) during the major depressive episode at intake, although the patients with subthreshold depressive symptoms received significantly higher levels of weekly antidepressant medication during their first well interval (t=2.67, df=94, p=0.009).

Survival analysis showed a relapse or recurrence of the next major depressive episode occurred more than three times faster for patients with subthreshold depressive symptoms than for asymptomatic patients (

Table 1). First relapse or recurrence of any depressive episode (major depressive episode, minor depression, or dysthymia) occurred more than 12 times faster for patients with subthreshold depressive symptoms than for asymptomatic patients. Overall, patients with subthreshold depressive symptoms had a 2.35 times higher odds of relapse to any type of depressive episode during any given week of follow-up.

After recovery from their major depressive episode at intake, 34.3% (N=24) of the asymptomatic patients remained free of any depressive episode during the remainder of follow-up, compared to only 7.7% (N=2) of the patients with subthreshold depressive symptoms (χ2=6.70, df=1, p<0.01). The recovery group with subthreshold depressive symptoms had significantly more subsequent depressive episodes of any type than the asymptomatic group, including more episodes of minor depression or dysthymia but not major depression. They had more chronic major depressive episodes (lasting more than 2 years) (z=2.24 p=0.25, Wilcoxon rank sum test) but not more dysthymic (chronic minor depressive) episodes. Median duration of interepisode well intervals was seven times shorter for the recovery group with subthreshold depressive symptoms than for the asymptomatic group (22 weeks versus 154 weeks, respectively) (z=6.11, p=0.0001, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

From resolution of the major depressive episode at intake until the end of follow-up, patients with asymptomatic recovery spent a much higher percentage of weeks free of depressive symptoms than the patients with subthreshold depressive symptoms. Patients with residual subthreshold depressive symptoms spent significantly more time than asymptomatic patients with symptoms at the subthreshold depressive symptom and minor depression or dysthymia levels.

Discussion

This is the first study we are aware of that documents that incomplete recovery from a first lifetime major depressive episode influences long-term outcome. We confirmed that “recovery” with residual subthreshold depressive symptoms is a strong, reliable clinical marker of rapid and frequent relapse to depressive episodes, as has been reported

(1,

2). More remarkable, we found that patients with residual subthreshold depressive symptoms had a significantly more severe and chronic course of illness, as evidenced by significantly more depressive episodes, more chronic major depressive episodes (more than 2 years), shorter well intervals, and far fewer weeks free of depressive symptoms. Thus, the early relapse or recurrence of depressive episodes associated with recovery with residual subthreshold depressive symptoms appears to lead to a more severe relapsing and chronic course.

Definitions of remission or recovery from an episode of major depressive disorder that include subthreshold depressive symptoms (e.g., Hamilton depression scale score of 7 or less

[8]) are not supported by these and other data

(1,

2,

7,

9). We submit that true remission or recovery from a major depressive episode occurs only with abatement of all ongoing residual symptoms, a conclusion supported by Fava et al.

(9), who showed the key factor in the delay of episode relapse was abatement of residual symptoms.

The presence of psychotic symptoms, lower antidepressant drug doses, and comorbidity of mental and substance use disorders did not account for long-term negative outcome. The finding that future chronicity was powerfully and prospectively predicted on the basis of residual subthreshold depressive symptoms after the first lifetime major depressive episode dictates that clinical and public health strategies should emphasize complete abatement of symptoms, even of the first lifetime major depressive episode.

Acknowledgment

This manuscript was reviewed by the Publications Committee of the NIMH Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression and has its endorsement. This study was conducted with the participation of the following investigators: W. Coryell, M.D. (Co-Chairperson, Iowa City); P.W. Lavori, Ph.D., M.T. Shea, Ph.D. (Providence, R.I.); J. Fawcett, M.D., W.A. Scheftner, M.D. (Chicago); J. Haley (Iowa City); J. Loth, M.S.W. (New York); J. Rice, Ph.D., and T. Reich, M.D. (St. Louis). Other contributors included N.C. Andreasen, M.D., Ph.D., P.J. Clayton, M.D., J. Croughan, M.D., G. L. Klerman, M.D. (deceased), R.M. Hirschfeld, M.D., M.M. Katz, Ph.D., E. Robins, M.D., R.W. Shapiro, M.D., R.L. Spitzer, M.D., G. Winokur, M.D. (deceased), and M.A. Young, Ph.D.