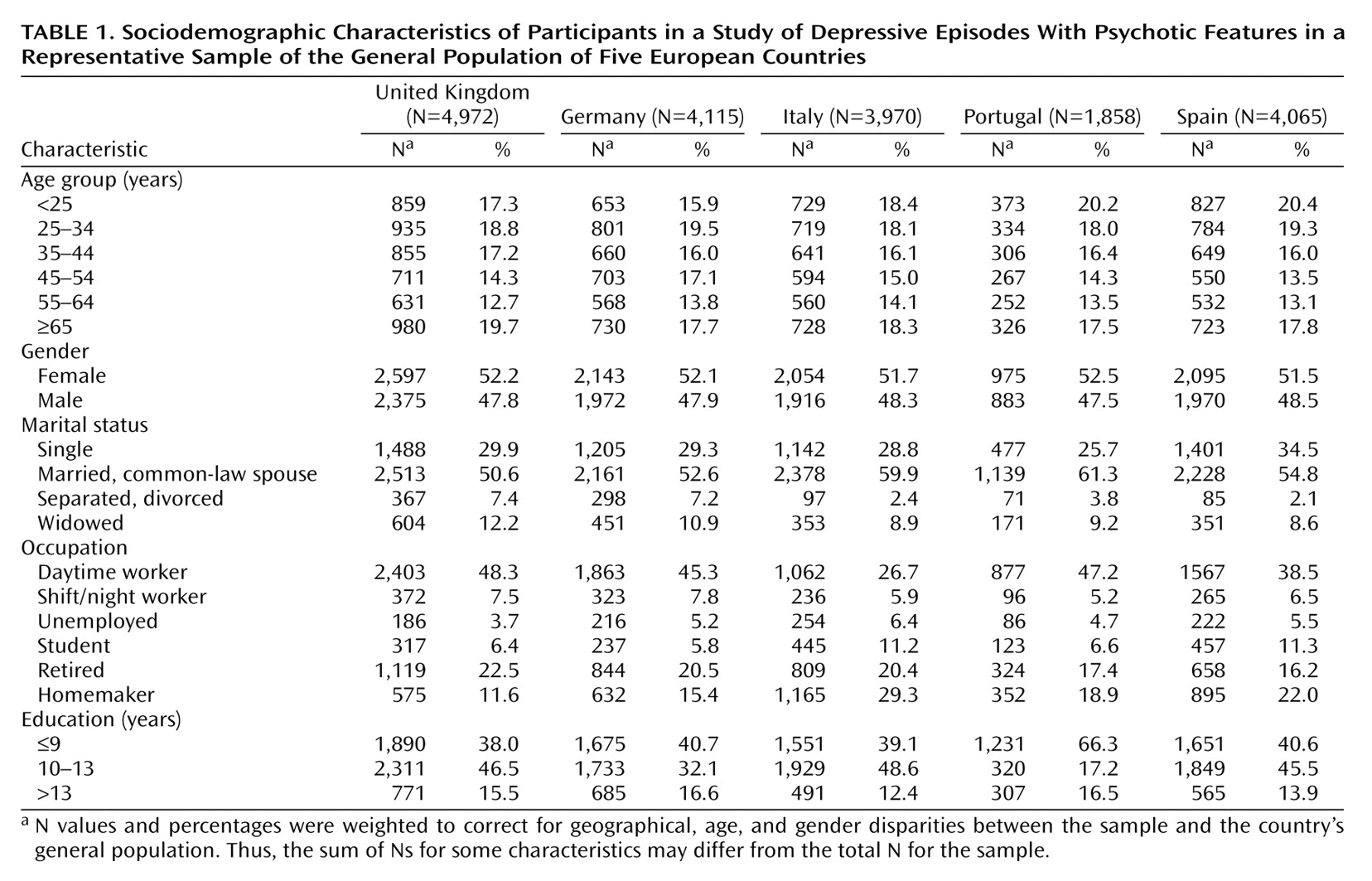

The sample included 18,980 subjects between 15 and 100 years old. Subjects from the United Kingdom represented 26.2% of the sample; German subjects, 21.7%; Spanish subjects, 21.4%; Italian subjects, 20.9%; and Portuguese subjects, 9.8%.

Some disparities in occupation between the countries were found. The percentage of participants who were working was lower in Italy and Spain than in the United Kingdom, Germany, and Portugal because there were more homemakers and students in Italy and Spain than in the other three European countries.

The level of education was translated into years of schooling to facilitate comparisons between the countries. In the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and Spain, basic education ends when the individual is 16 years old, while in Portugal an individual finishes basic education at age 15. Consequently, there were more participants with 9 years or less of schooling in Portugal than in the other countries.

DSM-IV Major Depressive Episode and Psychotic Features

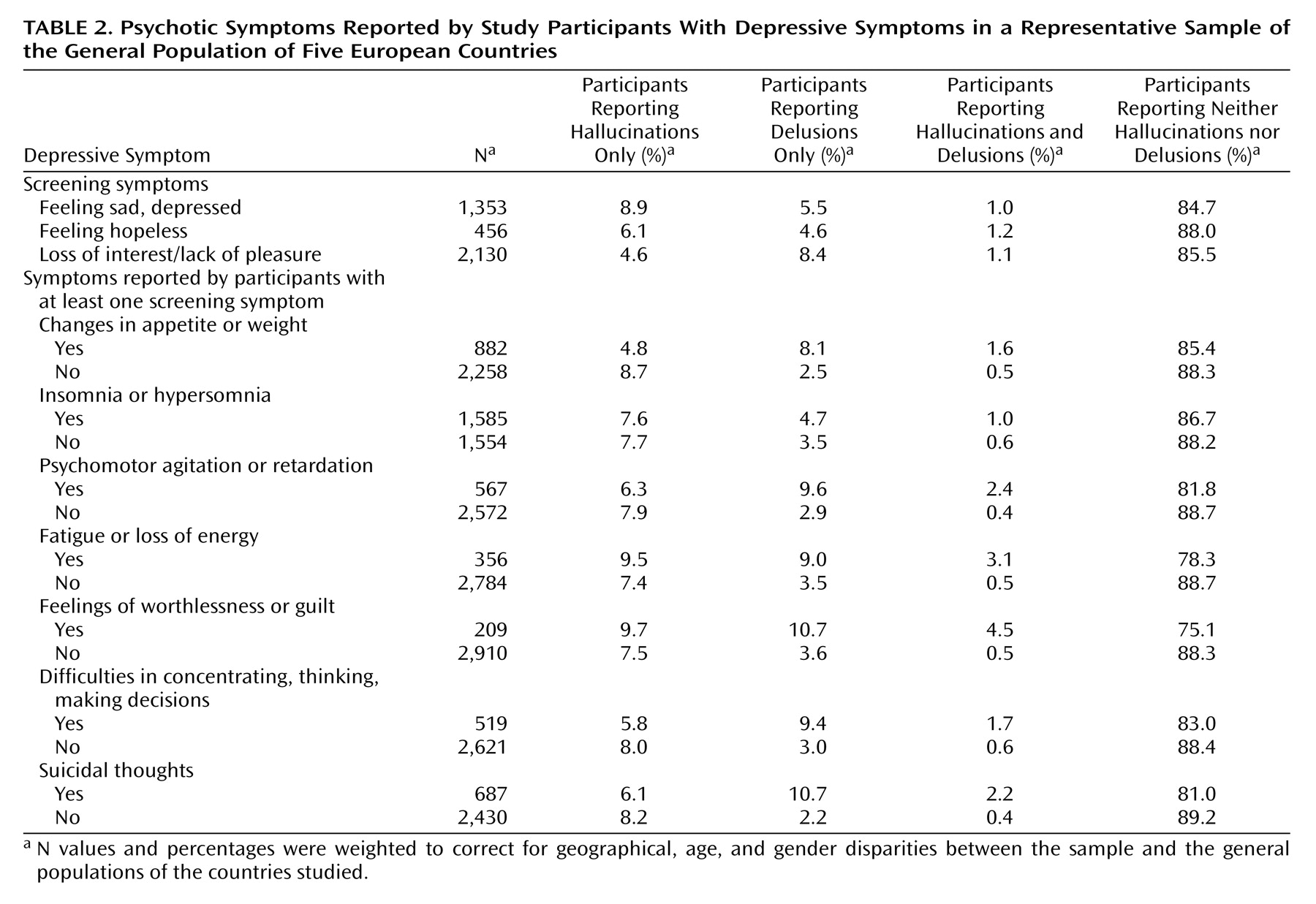

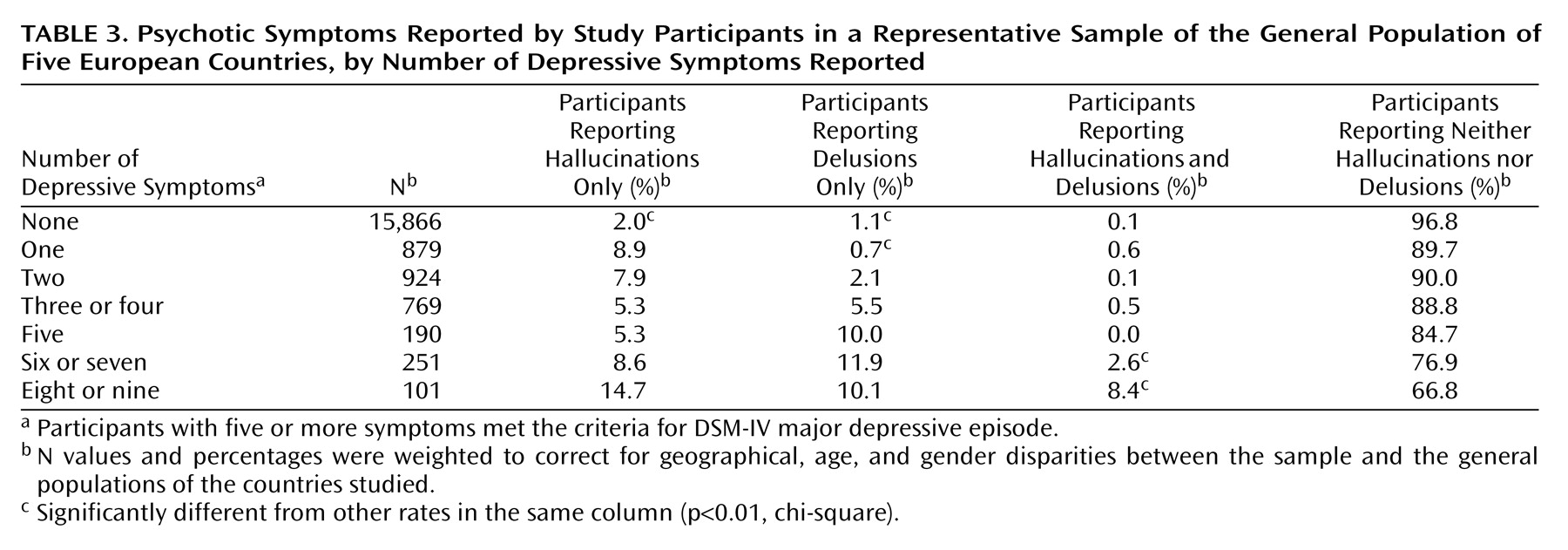

Overall, 454 subjects met all the criteria of a DSM-IV major depressive episode. Eighty-eight subjects with at least five of the nine depressive symptoms were eliminated in the differential diagnosis process. Overall, 10.6% of subjects with a major depressive episode had only delusions, 6.8% had only hallucinations, and 1.2% had both delusions and hallucinations. Therefore, subjects with a major depressive episode were nine times more likely to have delusions than subjects without a major depressive episode (odds ratio=8.9, 95% CI=6.4–12.3). The likelihood of having hallucinations was nearly three times higher in subjects with a major depressive episode than in those without (odds ratio=2.8, 95% CI=1.9–4.1). Finally, the likelihood of having both hallucinations and delusions was nine times higher in subjects with a major depressive episode than in those without (odds ratio=8.7, 95% CI=3.4–22.1).

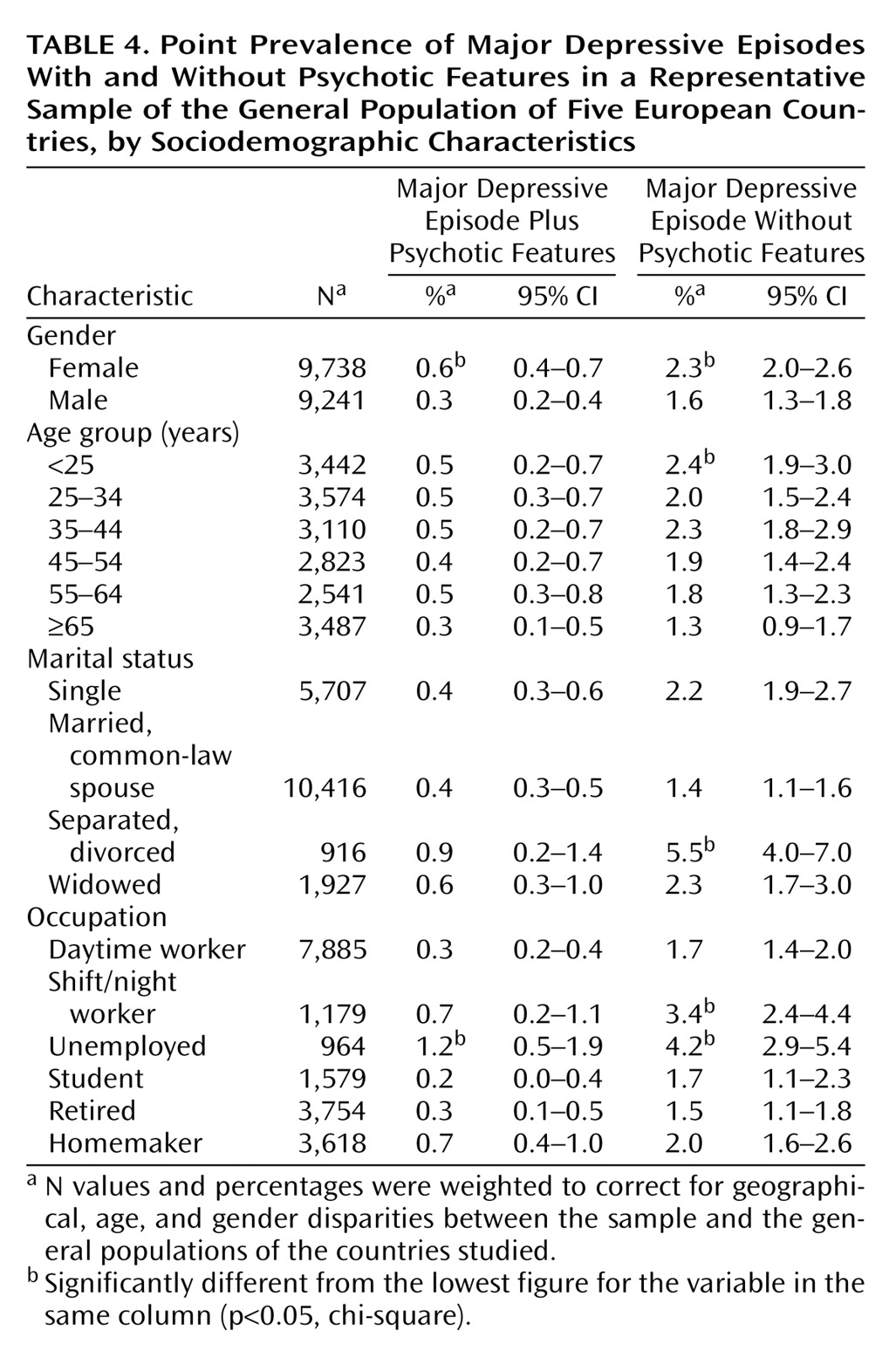

The point prevalence of a DSM-IV major depressive episode with or without psychotic features was 2.4% (95% CI=2.2%–2.6%). A major depressive episode with psychotic features had a prevalence of 0.4% (95% CI=0.35%–0.54%), and a major depressive episode without psychotic features had a prevalence of 2.0% (95% CI=1.9%–2.1%).

There was no significant difference between the countries for the point prevalence of a DSM-IV major depressive episode with psychotic features. The point prevalences were 0.5% (95% CI=0.3%–0.7%) in the United Kingdom, 0.4% (95% CI=0.2%–0.6%) in Germany, 0.2% (95% CI=0.1%–0.3%) in Italy, 0.5% (95% CI=0.2%–0.8%) in Portugal, and 0.2% (95% CI=0.1%–0.3%) in Spain.

Major depressive episodes with or without psychotic features both were more prevalent in women than in men. A major depressive episode without psychotic features was less prevalent in subjects age 65 years or older (

Table 4). Divorced or separated individuals were more likely to have a major depressive episode without psychotic features than were married subjects (

Table 4). Shift or night workers and unemployed subjects were more likely to have a major depressive episode with or without psychotic features than were daytime workers, students, or retired individuals (

Table 4). More specifically, unemployed men were six times more likely to have a major depressive episode with psychotic features (odds ratio=5.8, p<0.0001) and two times more likely to have a major depressive episode without psychotic features (odds ratio=2.2, p<0.05) than daytime workers. Male shift or night workers were more likely to have a major depressive episode without psychotic features (odds ratio=2.0, p<0.01) than were male daytime workers.

Among women, unemployed participants were three times more likely (odds ratio=2.9, p<0.01) to have a major depressive episode with psychotic features and two times more likely (odds ratio=2.5, p<0.001) to have a major depressive episode without psychotic features than those who were employed. Shift or night workers were also three times more likely (odds ratio=2.7, p<0.05) to have a major depressive episode with psychotic features and two times more likely (odds ratio=2.1, p<0.01) to have a major depressive episode without psychotic features than were daytime workers.

It is interesting to note that the frequency of some depressive symptoms changed with the occupation status. For example, more than 40% of depressed male shift or night workers reported changes in appetite or weight; this proportion was at least two times higher than in other occupation categories. This was not the case with depressed women. Suicidal thoughts were at least two times more frequent in unemployed depressed men (25%), followed by depressed male shift or night workers (21%), compared with other occupation categories. This pattern was also observed in unemployed women.

Finally, subjects with a major depressive episode with psychotic features were twice as likely to have consulted a health professional for treatment of depression in the past than were subjects with a major depressive episode without psychotic features (28.0% versus 18.3%) (χ2=4.03, df=1, p<0.05). The duration of the current episode was also longer in subjects with a major depressive episode with psychotic features than in those without psychotic features, but the difference was not significant (mean duration in months=20.0 versus 15.6) (F=2.35, df=1, 331, p=0.13).