The risk of relapse in mood disorders is 50% in the year after an index episode

(1). In research settings, mood stabilizers significantly reduce this rate

(2). However, there is a significant efficacy-effectiveness gap

(3). Medication nonadherence and subtherapeutic plasma levels are associated with poorer clinical outcome.

Subtherapeutic plasma levels are not always a result of medication nonadherence but may reflect clinician and patient preference

(4) or physiological variability

(1,

4). Individuals may adhere poorly to a regimen of mood stabilizers but still have plasma levels within the therapeutic range. The possible independent contribution to outcome of nonadherence has not been explored, although Irvine et al.

(5) found that individuals who were adherent to placebo treatment after myocardial infarction had a significantly better prognosis than those who were poorly adherent to active treatments. The current study prospectively monitored psychiatric hospital admissions in groups of patients with varying levels of adherence to treatment with mood stabilizers and plasma levels.

Method

With the approval of the ethics committee, we identified 146 individuals who were 18 years old or older, met DSM-IV criteria for a unipolar or bipolar mood disorder, were in contact with psychiatric outpatient services, and had at least one recorded plasma level of mood stabilizer (lithium, carbamazepine, and sodium valproate) within the last 3 months. All patients included in the study provided written informed consent.

Patients participated in a semistructured interview

(6), which yielded demographic data, DSM-IV diagnosis, and illness and treatment details. Patients also completed the Tablet Routines Questionnaire

(7), which assessed self-reported medication adherence. Partial adherence was defined as missing 30% or more of prescribed mood stabilizers in the last month

(6,

8).

Data on plasma levels from the assays undertaken in the 3 months before the interview were reviewed to classify patients into those with mean plasma levels within or below the normal range for the laboratory. The normal ranges were 0.4–1.0 mmol/liter for lithium, 6–10 μg/ml for carbamazepine, and 50–100 μg/ml for sodium valproate. Psychiatric admissions over the 18 months following the interview were noted for each patient.

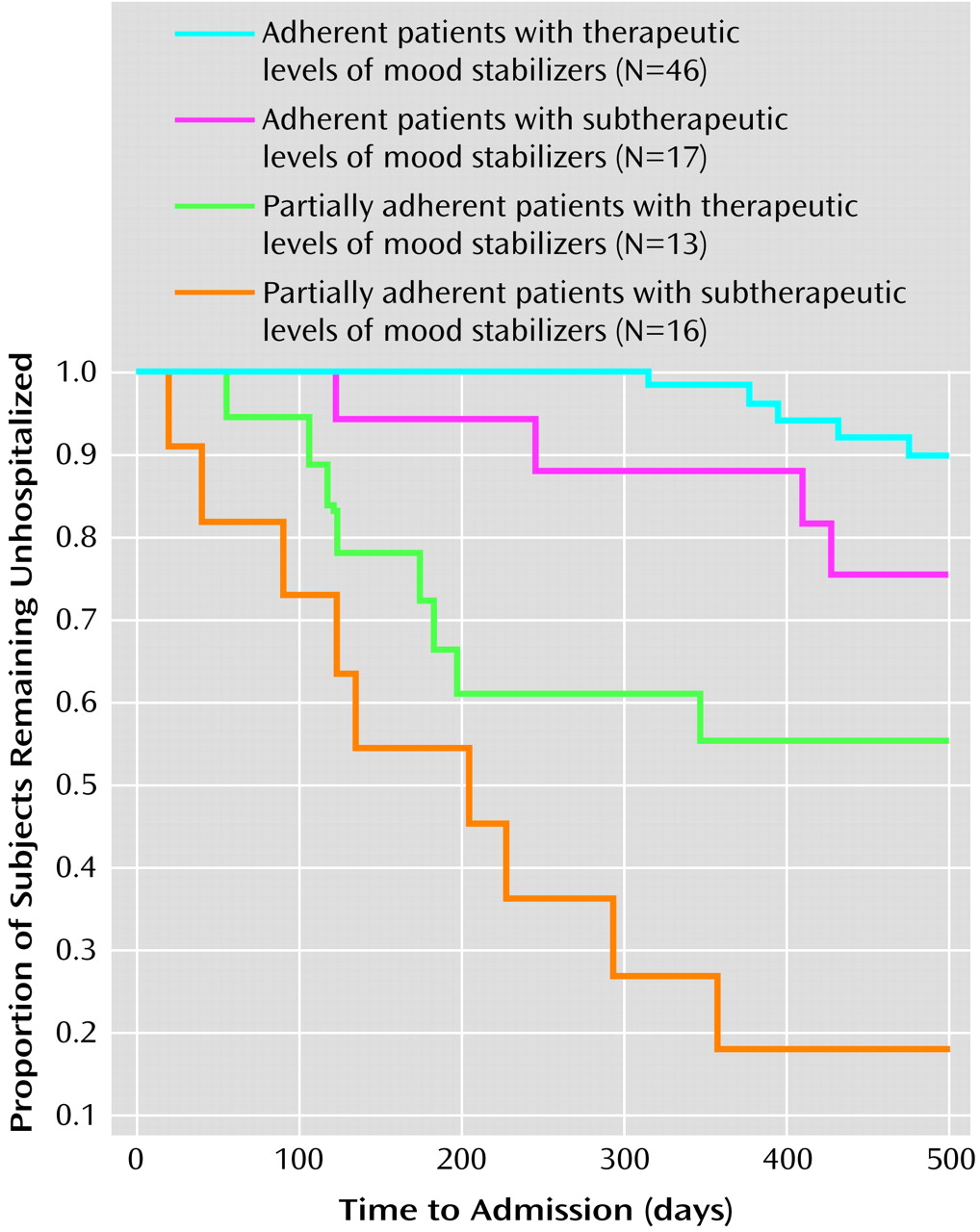

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was undertaken to depict the cumulative probability of admission in four groups: adherent patients with therapeutic levels of mood stabilizers, adherent patients with subtherapeutic levels of mood stabilizers, partially adherent patients with therapeutic levels of mood stabilizers, and partially adherent patients with subtherapeutic levels of mood stabilizers. Cox regression analysis was undertaken to explore demographic and clinical predictors of outcome. (When the analyses were repeated for patients receiving lithium only and for patients with bipolar disorders only, the pattern of results remained the same.)

Results

Of 146 potential participants, 48 did not take part. The final study group comprised 20 individuals with unipolar disorder and 78 with bipolar disorders (68 of these had bipolar I disorder). Their mean age was 43.4 years (range=18–71), and 57 were women. The mean age of the patients at first episode of mood disorder was about 26 years (range=14–56); the median number of episodes was 5 (range=1–14); 89% had a history of psychiatric hospitalization. Patients had been prescribed prophylactic medication for 2.0–17.5 years (mean=5.9 years, SD=4.3). Seventy-two patients were being prescribed lithium, either alone or in combination with other mood stabilizers.

Six patients were not classified as to medication adherence or plasma level. Twenty-nine (32%) of the remaining patients met criteria for partial adherence. The index plasma level was below the recommended therapeutic range in 33 patients (36%). When groups were defined by adherence status and index plasma level, 46 patients were classified as adherent with plasma levels in the therapeutic range, 17 as adherent with subtherapeutic levels, 13 as partially adherent with levels in the therapeutic range, and 16 patients as partially adherent with subtherapeutic levels of mood stabilizer.

Over 18 months, 27 out of the 92 patients experienced at least one hospital admission (range=1–5). The cumulative probability for admission was 29%. Survival analysis revealed significant differences in admissions among groups (log rank test=42.6, df=3, p=0.001). As shown in

Figure 1, the probability of admission in the adherent patients with therapeutic (four of 46) or subtherapeutic (four of 17) levels of mood stabilizers and the partially adherent patients with therapeutic (six of 13) or subtherapeutic (13 of 16) levels of mood stabilizers was 9%, 24%, 46%, and 81%, respectively. Cox regression analysis demonstrated that group was the most important predictor of hospital admission (χ

2=39.6, df=8, p=0.001). The effect of male gender (p=0.06) just failed to reach statistical significance; younger age (p=0.10) showed a similar trend. The mean number of admissions was 0.21 (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.01–0.42) in the group of adherent patients with therapeutic levels of mood stabilizers, 0.31 (95% CI=0.08–0.63) in the group of adherent patients with subtherapeutic levels of mood stabilizers, 0.72 (95% CI=0.22–1.23) in the group of partially adherent patients with therapeutic levels of mood stabilizers, and 1.45 (95% CI=0.76–2.15) in the group of partially adherent patients with subtherapeutic levels of mood stabilizers. These group differences remained significant even when we controlled for demographic and illness factors (F=7.96, df=8, 83, p=0.01).

Discussion

The study has methodological flaws. First, participants represented only 67% (98 of 146) of the potential study group. We do not know whether nonparticipants were less medication adherent or had therapeutic plasma levels. Second, we did not assess comorbidity, which may adversely affect adherence and prognosis

(9). Third, the plasma levels we considered therapeutic will not be regarded as optimal by other centers. Fourth, we used psychiatric hospital admission rather than relapse as the primary outcome measure. Although this represents the worst clinical and economic outcome, it ignores other aspects of clinical or social functioning.

We found that one in three patients omitted 30% or more of their medication. This rate is comparable to that reported in previous studies of mood disorders and chronic nonpsychiatric medical disorders

(3,

5,

8,

9). The finding that 33 out of 92 patients had suboptimal serum plasma levels of mood stabilizers is also comparable to findings of other studies

(1,

3,

10). However, groups defined by partial adherence or suboptimal plasma levels were not contiguous.

The cumulative probability of admission in this group of patients was about 30% and is equal to or better than that reported previously

(1–

4,

10) This overall good outcome was mainly a function of the very low admission rate (<10%) in patients who were highly adherent to their medication and had therapeutic plasma levels. Interestingly, the subgroup of patients reporting partial adherence and therapeutic serum plasma levels demonstrated significantly worse outcome than adherent patients with subtherapeutic plasma levels. It is possible that the partially adherent patients with therapeutic levels of mood stabilizers engaged in erratic cycles of adherence, took “loading” doses of mood stabilizers before plasma checks, or had higher than expected plasma levels for physiological reasons. Likewise, the group of adherent patients with subtherapeutic levels of mood stabilizers may be individuals who fail to acknowledge nonadherence, who have lower plasma levels by preference, or who have physiologically induced variability. Such problems cannot be detected by the methodology employed. Nevertheless, this study suggests that level of adherence may have an independent effect on prognosis in mood disorders. In nonpsychiatric medicine, self-reported adherence status is viewed as a useful “proxy” measure of the likelihood that an individual will engage in other healthy behaviors and demonstrate an adaptive style of coping with the disorder

(5). If our findings are replicated, this notion may be equally applicable to psychiatry.