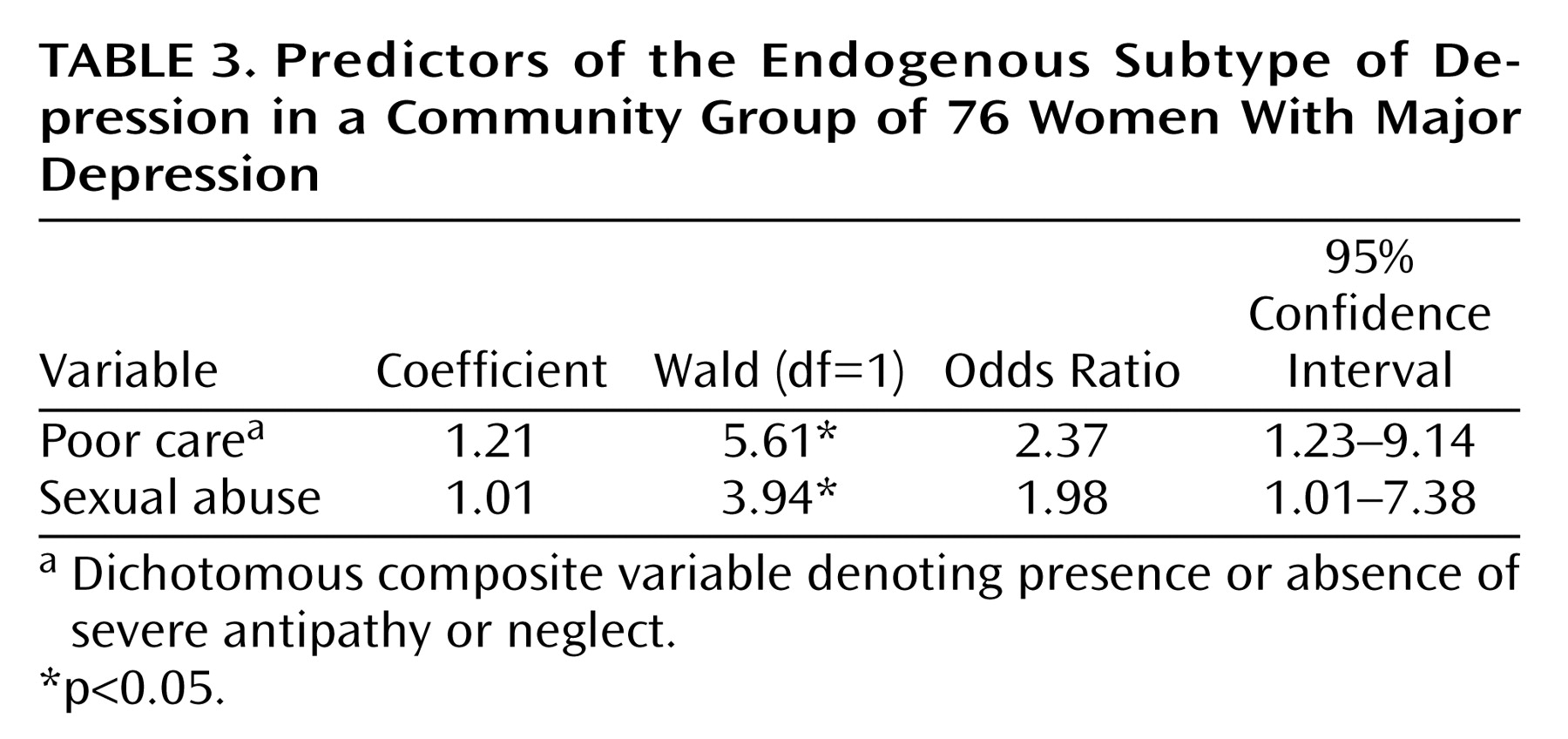

Kraepelin originally characterized endogenous depression by 1) a distinct pattern of symptoms (e.g., anhedonia, morning worsening, psychomotor disturbance), 2) a presumed biogenetic etiology, and 3) an absence of precipitating stressors

(4,

5). By contrast, the more loosely defined nonendogenous subtype was traditionally conceptualized as a reaction to environmental adversity. Many studies have failed to find consistent support for a preferential relationship of recent precipitating stressors to nonendogenous depression (see reference

6). However, only recently have studies begun investigating the role of childhood adversity in validating this subtype distinction.

Parker and colleagues

(7,

8) found that poor parental care and high parental control (“affectionless control”), as measured by the Parental Bonding Instrument

(9), were preferentially associated with nonendogenous depression. Other adverse childhood experiences were also associated with nonendogenous depression in these studies (e.g., dysfunctional parental marriage, emotional abuse, and rejection

[9], but not childhood physical or sexual abuse

[10]). This research provides important support for the distinction between nonendogenous and endogenous depression and suggests that nonendogenous depression may be more strongly influenced by the effects of childhood adversity than endogenous depression.

Second, previous studies have examined only the univariate associations among particular adverse childhood experiences and depression onset or depression subtype. However, it is unclear which specific experiences emerge as most strongly associated with these outcomes in multivariate models. For example, is childhood neglect more strongly associated with nonendogenous depression than childhood physical or sexual abuse? Therefore, the second goal of the present study was to examine the relative contributions of different types of childhood adversity to depression subtypes.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

In order to identify covariates to be included in the primary analyses, preliminary chi-square tests and independent-sample t tests were performed to examine the basic associations of the diagnostic groups and the adversity variables with age, marital status, education, occupation, number of previous episodes, and treatment status. Only the relationship between age and sexual abuse was significant: subjects with a history of sexual abuse were significantly younger (mean=33.95, SD=10.04) than those without such a history (mean=41.03, SD=11.20) (t=2.90, df=74, p<0.005). Results of the primary analyses including age as a covariate did not differ from the uncontrolled analyses, so only the uncontrolled results are presented.

On the Hamilton depression scale, those with endogenous depression scored significantly higher (mean=21.74, SD=4.22) than did those with nonendogenous depression (mean=15.87, SD=4.60) (t=5.66, df=74, p<0.0001). Those with histories of sexual abuse also scored significantly higher on the Hamilton depression scale (mean=20.15, SD=4.49) than did those without such a history (mean=16.17, SD=5.18) (t=3.52, df=74, p<0.01). Finally, Hamilton depression scale scores were related to supervision (F=3.11, df=2, 73, p<0.05). Post hoc tests revealed that those with lax supervision scored significantly higher (mean=19.96, SD=5.23) than did those with moderate supervision (mean=16.66, SD=5.20) (p<0.05).

Primary Analyses: Childhood Adversity and Depression Subtype

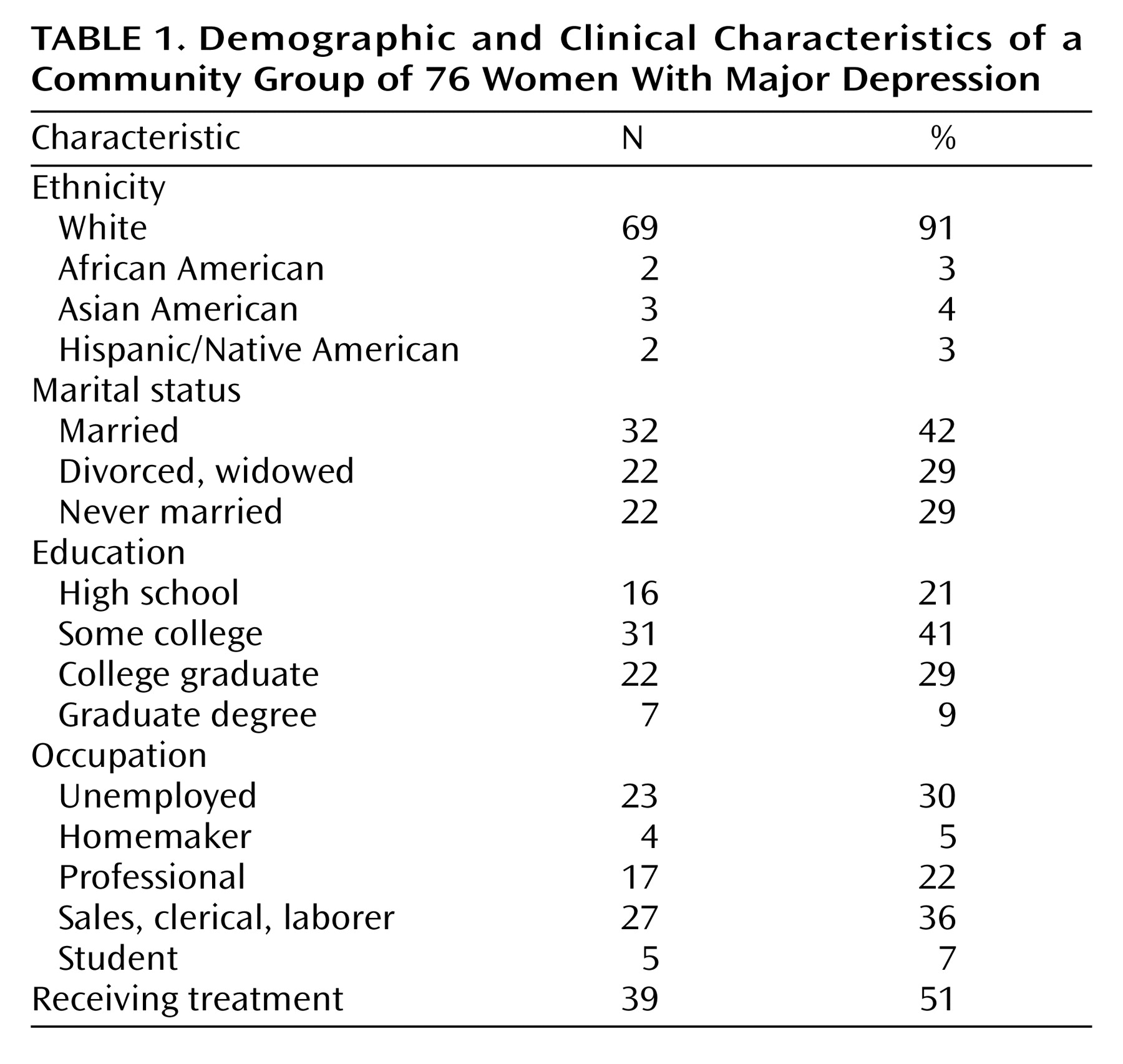

The prevalence and severity of the eight adversity variables among the 76 depressed women are presented in

Table 2. Additional descriptive characteristics for physical and sexual abuse are as follows. The mean age at onset of sexual abuse was 9.62 years (SD=5.33), and the mean age at onset of physical abuse was 4.12 years (SD=4.62). Fifty-five percent (N=22) of those with sexual abuse experienced only one incident, while the rest experienced abuse ranging in duration from 3 to 207 months (median=30). The mean duration for physical abuse was 118.86 months (SD=59.78). Twenty-eight percent of sexual abuse cases (N=11) were perpetrated by a close relative, 50% (N=20) were perpetrated by a nonrelative or stranger, and 23% (N=9) experienced sexual abuse by multiple perpetrators, both relatives and nonrelatives. Physical abuse was perpetrated by parents in all cases.

Because of low numbers in some cells, and in order to simplify interpretation, three adversity variables (antipathy, neglect, and discord) were collapsed into nonsevere (ratings of some or little) and severe (ratings of moderate or marked) groups. A series of two-tailed two-by-two and two-by-three Pearson chi-square analyses were conducted to test the univariate associations among depression subtype and the adversity variables. Fisher’s exact test of significance was applied to the two-by-two chi-square analyses. The likelihood ratio test was applied to the sexual abuse analysis because of small expected frequencies.

In direct contrast to previous findings, endogenous depression was approximately twice as likely to be diagnosed in those with severe levels of physical abuse (χ2=7.00, df=2, p<0.05), sexual abuse (χ2=5.92, df=2, p<0.05), antipathy (χ2=5.69, df=1, p<0.05), and neglect (χ2=4.68, df=1, p<0.05) than in those with nonsevere adversity. In addition, while the relationship between subtype and discord was not significant, those with marked levels of discord were more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with endogenous depression (65%) than those with moderate (32%), some (33%), or little/no discord (36%). Furthermore, endogenous depression was more than twice as likely to be diagnosed in those with lax and high levels of supervision (χ2=8.40, df=2, p<0.05) and discipline (χ2=7.47, df=2, p<0.05) than in those with moderate levels of these variables.

Multivariate Analyses

In order to examine the relative contributions of the aforementioned significant childhood adversity variables to endogenous versus nonendogenous depression, a forward stepwise logistic regression was performed. A stepwise model was chosen instead of a theoretically driven entry model because we had no a priori hypotheses regarding the relative importance or temporal ordering of childhood adversity variables to the model.

To avoid problems with multicollinearity, two composite variables were created because of the high intercorrelations between antipathy and neglect (r=0.74, df=74, p<0.001) and between supervision and discipline (r=0.54, df=74, p<0.001). The dichotomous composite variable “poor care” denoted the presence or absence of severe antipathy or neglect. The composite variable “control” had three levels: 0=moderate supervision and discipline; 1=high supervision or discipline; 2=lax supervision or discipline. Therefore, the predictors included in the stepwise procedure were physical abuse, sexual abuse, poor care, and control.

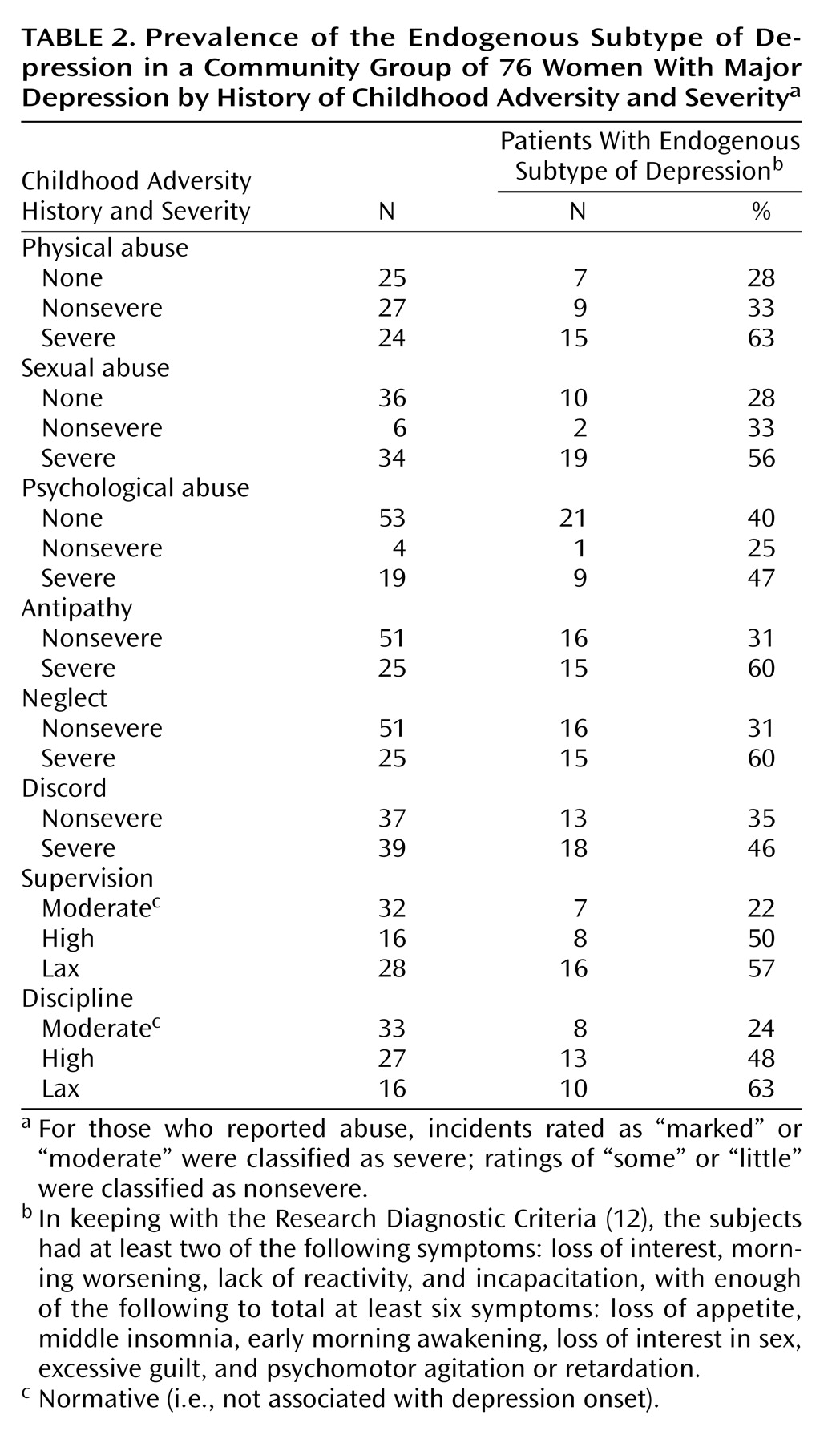

As seen in

Table 3, the forward stepwise model identified poor care and sexual abuse as significant predictors (χ

2=11.62, df=2, p<0.005), with 68% of participants correctly classified to endogenous versus nonendogenous groups. The odds ratios indicated that women with poor care were almost two and a half times as likely to be diagnosed with endogenous depression than those without. Similarly, those with severe sexual abuse were almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with endogenous depression than those without. Physical abuse and control, despite displaying univariate relationships with endogenous depression, were no longer significant when poor care and sexual abuse were included in the model.

Follow-Up Control Analyses: Sexual Abuse and Depression Severity

As noted in the preliminary analyses, sexual abuse was significantly associated with overall depression severity, as assessed by the Hamilton depression scale. This finding is interesting in and of itself but raises the question of whether depression severity alone can account for the strong relationship between sexual abuse and endogenous depression. That is, do those with severe sexual abuse score higher on a broad, uniformly distributed range of depression symptoms, or is sexual abuse associated with higher scores on only those symptoms that make up the supposedly qualitatively distinct syndrome of endogenous depression? The severity confound is challenging to address statistically, since many Hamilton depression scale symptoms are also symptoms of endogenous depression. Therefore, the Hamilton depression scale and the endogenous depression measure are highly collinear, and covarying Hamilton depression scale scores statistically would partial out most of the variance in the endogenous depression measure.

We chose instead to descriptively examine the univariate correlations among severe sexual abuse and the individual Hamilton depression scale symptoms. We found that severe sexual abuse was associated with higher scores on the endogenous symptoms of guilt (r=0.27, df=74, p<0.05) and psychomotor retardation (r=0.27, df=74, p<0.05). The only nonendogenous symptom to significantly discriminate severe versus nonsevere levels of sexual abuse was suicidal ideation (r=0.23, df=74, p<0.05). These results provide further evidence, to be pursued more rigorously in future research, that severe sexual abuse is significantly and preferentially associated with the qualitatively distinct symptoms of endogenous depression.

Discussion

In the present study, severe physical abuse, sexual abuse, antipathy, and neglect, as well as both high and lax levels of supervision and discipline, were significantly associated with endogenous versus nonendogenous depression. Sexual abuse and poor care, a composite of antipathy and neglect, were most strongly associated with endogenous depression in a multivariate model. Sexual abuse was also associated with more severe depression and higher levels of suicidal ideation, consistent with prior research

(15–

17). Together, these results suggest that severe childhood adversity, particularly sexual abuse, is associated with severe endogenous depression with significant suicidal ideation. This profile is of great concern clinically, since it has been associated with higher rates of relapse and recurrence

(5) as well as with risk for more active suicidal intent.

The present results were inconsistent with previous studies that had demonstrated a preferential association between childhood adversity and nonendogenous depression

(7,

8). There are a number of potential explanations for this discrepancy. First, previous studies relied on mean Parental Bonding Instrument scores and categorizations of abuse as present or absent

(8,

9). By contrast, we examined more fine-grained distinctions in the severity of childhood adversity. We found that while nonsevere levels of childhood adversity were indeed associated with a higher risk of nonendogenous depression, severe childhood adversity was consistently associated with at least double the risk of endogenous depression. Exploiting the richness of the descriptive data provided by the Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse interview, which assigns continuous threat levels, may have allowed this interesting crossover pattern to emerge.

Second, one of the strengths of the study by Parker and colleagues

(7) was its use of several diagnostic systems. However, significant associations only emerged when using a “clinical” definition of subtypes, and no differences were found when subtypes were defined according to DSM-IV, Newcastle

(18), or CORE

(19) criteria. Nonendogenous depression in this “clinical” system was defined, in part, by the presence of “ongoing dysfunctional depressogenic attitudes.” However, a depressogenic cognitive style has been associated with a bias to recall negative information and to magnify the negative aspects of situations

(20). Therefore, individuals in Parker et al.’s nonendogenous group were, by definition, more likely to magnify the negative aspects of their childhood experiences. As a result, it is possible that a depressogenic recall bias may account, in part, for the association between childhood adversity and nonendogenous depression in this previous study. This issue is particularly prominent given Parker et al.’s use of the Parental Bonding Instrument, which does not encourage respondents to support their impressions with behavioral evidence and does not probe for potential positive information.

By contrast, a diagnosis of RDC endogenous depression relies on observable depression symptoms as opposed to inferred personality characteristics. However, the RDC have been criticized for being less stringent than other definitions, such as DSM-IV melancholia

(21). In the present study, only 10 women met criteria for melancholia, thus precluding multivariate analyses. Nevertheless, when we performed univariate chi-square analyses of the relationship between melancholia and the individual Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse scales, we replicated entirely our results obtained by using RDC endogenous depression, thus further strengthening the present findings.

Since the many diagnostic systems that exist for endogenous depression are each made up of slightly different criteria, each system diagnoses slightly different groups of patients. Such discrepancies in the definition of endogenous depression across studies make comparison of results difficult and limit research investigating the predictive validity of the endogenous depression syndrome. Therefore, we urge researchers in this area to examine the individual symptom profiles of those with different types of childhood adversity. For example, the present results indicate that severe sexual abuse was associated with suicidal ideation along with traditional endogenous symptoms. Future research along these lines may suggest that the criteria for endogenous depression need to be revised for those with childhood adversity.

Finally, the present study group included women only. While Parker and colleagues

(7) did not report any sex differences in the relationship between childhood adversity and depression subtype in their patient group, this is still an important methodological difference between the two reports that may help to account for the discrepant findings. It is of interest that the relationship of sexual abuse to severe depression in the present study is consistent with the findings of Gladstone et al.

(10), who also used a female patient group. To our knowledge, there have been no systematic attempts to chart sex differences in the relationship of childhood adversity to endogenous versus nonendogenous depression, and we suggest this as an area of future research.

Future studies are required to elucidate potential mediators or moderators of the relationship between childhood adversity and endogenous depression. For example, one might wonder how recent stressful life events or depression recurrence contribute to this model. In preliminary analyses not included in the present results, we examined life events with the Life Events and Difficulties Schedule

(22), a rigorous contextual interview and rating system. Neither “severe” events (i.e., events rated as marked or moderate on a 4-point index of threat and believed to be most etiologically central in depression) nor total number of events of any threat level were related to depression subtype. This was the case when recent events were examined as mediators, moderators, or as independent predictors of subtype. In addition, we did not find evidence for an association between childhood adversity and first-onset versus recurrent depression, nor did depression recurrence mediate or moderate the relationship between childhood adversity and depression subtype. Speculation regarding the reasons for these null results is outside of the main focus of the present study, and we urge researchers to pursue these associations more directly.

Endogenous depression has traditionally been associated with a neurobiological etiology, and it is compelling to find it here preceded by severe environmental adversity. However, a large body of research suggests that severe, prolonged, and uncontrollable stress, such as that inherent in severe sexual abuse and poor parental care, has enduring effects on developing brain networks

(23–

25). Furthermore, prolonged and uncontrollable stress has been proposed as an animal model of anhedonia, provoking behavioral signs analogous to the symptoms of endogenous depression

(26). While the present results clearly require replication before undertaking detailed investigations into mediating mechanisms, one intriguing possibility is that severe childhood adversity may have neuropathological consequences that mediate the development of endogenous depression in adulthood. Additional and complementary mediating mechanisms are also possible, and multivariate models are needed to examine the respective contributions of many different variables (e.g., family history, childhood adversity, recent life events, and neuropathological mechanisms) to the development of endogenous versus nonendogenous depression.

As with all retrospective studies, biases are possible in the recall of childhood experiences, especially since all participants were currently depressed. The Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse interview addresses this concern in a more rigorous fashion than that provided by self-report questionnaires, since respondents are probed during the interview about potentially neglected positive information. Furthermore, ratings of childhood adversity are made by judges who are blind to diagnostic subtype. Another limitation of the present design is that it was based on a community group of women, and, therefore, results may not generalize to men or to patient groups. Nevertheless, Hamilton depression scale scores of the present participants were comparable to those reported in most outpatient study groups in the literature. In addition, more than half of the study group was currently receiving outpatient treatment in the community, and no differences were noted on any study variables between this subgroup and those not receiving treatment.

The present study was also limited by its cross-sectional design, which precluded analysis of the relationship between childhood adversity and endogenous depression across repeated episodes. In particular, controversy exists regarding whether endogenous depression is a stable syndrome that expresses itself similarly across recurrent episodes

(27,

28) or whether the phenomenology of depression changes across episodes

(29). Future research investigating the relationship of childhood adversity to the phenomenology of depression across the lifetime course of the disorder is necessary to help resolve this issue.

In summary, severe levels of childhood adversity were significantly associated with severe endogenous depression. These results may enlarge thinking about the traditional etiological distinction between endogenous and nonendogenous depression and are consistent with emerging research outlining the neuropathological consequences of childhood adversity. Such a symptom profile is of great concern clinically, since it is associated with higher rates of relapse and recurrence

(5). Therefore, we suggest that individuals with severe abuse and poor parental care be identified early through regular clinical assessment for childhood adversity and targeted for rigorous acute and maintenance interventions.