Previous research has suggested that childhood adversities may contribute to the development of eating disorders. Individuals with eating disorders are more likely than those without eating disorders to report a history of childhood maltreatment

(1–

3), other chronic or episodic childhood adversities

(4–

7), and problematic relationships with their parents

(1,

8–13). These findings have enabled researchers to generate hypotheses about the role of childhood adversities in the development of eating disorders

(14). However, nearly all of the studies that have examined the association between childhood adversities and eating disorders have been cross-sectional case-control investigations. It is problematic to make inferences about risks associated with the onset of eating disorders among individuals in the general population on the basis of cross-sectional studies of patients with eating disorders.

To investigate potential risk factors that may contribute to the development of eating disorders, prospective longitudinal research with a sizable community-based sample is necessary. Potential risk factors must be assessed before the development of the eating disorders. Covariates such as childhood eating problems and childhood temperament that may account for the association between the risk factors and the eating disorders must be controlled statistically. Our review of the literature indicates that no investigation of the association between a wide range of childhood adversities and offspring risk for the development of eating disorders that we located met all of these methodological criteria.

In the study reported here, data from the Children in the Community Study, a prospective longitudinal investigation, were used to examine whether maladaptive parental behavior, childhood abuse and neglect, other childhood adversities, and socioeconomic variables were associated with elevated risk for the development of problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood. Statistical procedures were used to control for the effects of offspring age, childhood temperament, childhood eating problems, parental psychopathology, and co-occurring childhood adversities.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The current analyses were conducted with data from 782 families for whom information was available on childhood adversities and problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood. These families are a subset of 976 randomly sampled families from two upstate New York counties. The mothers were interviewed in 1975, 1983, 1985–1986, and 1991–1993

(15,

16). One randomly selected child from each family was interviewed in 1983, 1985–1986, and 1991–1993. The sample was generally representative of families in the northeastern United States with regard to socioeconomic status and most demographic variables; the sample reflected the region in having high proportions of Catholic (54%) and white (91%) participants

(16). The mean age of the 397 male and 385 female offspring in the sample was 6 years (SD=3) in 1975, 14 years (SD=3) in 1983, 16 years (SD=3) in 1985–1986, and 22 years (SD=3) in 1991–1993. Study procedures were approved according to appropriate institutional guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained after the interview procedures were fully explained. The youths and their mothers were interviewed separately, and both interviewers were blind to the responses of the other informant. Additional methodological information is available from previous reports

(15,

16).

Assessment

Offspring psychiatric disorders and childhood temperament

The parent and youth versions of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children

(17) were administered in 1983, 1985–1986, and 1991–1993 to assess offspring psychiatric disorders. Both the parents and the youths were interviewed because the use of multiple informants tends to increase the reliability and validity of psychiatric diagnoses

(18,

19). A symptom was considered present if it was reported by either informant. Previous research has indicated that the reliability and validity of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children as employed in the present study are comparable to those of other structured interviews

(20).

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children items assessed the diagnostic criteria for eating disorders, as well as a wide range of specific eating and weight problems. Computer algorithms were subsequently developed to determine whether individuals met the DSM-IV criteria for eating disorders. A diagnosis of eating disorder not otherwise specified (e.g., anorexia without amenorrhea, binge eating disorder) was made if clinically significant eating disorder symptoms were present but the full criteria for anorexia nervosa, binge eating disorder, or bulimia nervosa were not met. Participants were defined as obese if their weight was ≥150% of normal body weight and ≥2 standard deviations above the sample mean. Participants were defined as having low body weight if their weight was ≤90% of normal body weight and ≥2 standard deviations below the sample mean. Neither obesity nor low body weight was considered an eating disorder unless the individual had symptoms that met the DSM-IV criteria for an eating disorder. Additional data were drawn from the interviewer’s observations of the child’s behavior during the interview.

Ten dimensions of difficult childhood temperament were assessed by using the Disorganizing Poverty Interview (15) during the 1975 maternal interviews: 1) clumsiness-distractibility, 2) nonpersistence-noncompliance, 3) anger, 4) aggression to peers, 5) problem behavior, 6) temper tantrums, 7) hyperactivity, 8) crying-demanding, 9) fearful withdrawal, and 10) moodiness. Children with severe problems in one or more of these domains were identified as having a difficult temperament. Previous research has supported the reliability and validity of these 10 indices of childhood temperament

(21).

Parental psychiatric symptoms

Interview items used to assess maternal psychiatric symptoms in 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986 were obtained from the Disorganizing Poverty Interview, the California Psychological Inventory

(22), the Hopkins Symptom Checklist

(23), and instruments that assessed maternal alienation

(24), rebelliousness

(25), and other maladaptive traits

(26,

27). Paternal alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and antisocial behavior were assessed during the 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986 interviews by using the Disorganizing Poverty Interview. In addition, lifetime histories of parental anxiety, depressive, disruptive, and substance use disorders were assessed during the 1991–1993 maternal interview by using items adapted from the New York High Risk Study Family Interview

(28). Additional data were provided by the interviewer’s observations of the mother’s behavior during the interview. Parental eating disorders were not assessed. Data regarding age at onset permitted identification of maternal and paternal psychiatric disorders that were evident by 1985–1986. Computerized diagnostic algorithms were developed by using the items from these instruments to assess the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for maternal personality disorders, paternal antisocial personality disorder, and maternal and paternal anxiety, depressive, disruptive, and substance use disorders.

Maladaptive parental behavior

The Disorganizing Poverty Interview and the measures of parental child-rearing attitudes and behaviors that were administered during the maternal interviews were used to assess maternal enforcement of rules, the presence of loud arguments between the parents, maternal educational aspirations for the child, maternal possessiveness, maternal use of guilt to control the child, maternal difficulty controlling anger toward the child, parental cigarette smoking, paternal assistance to the child’s mother, paternal role fulfillment, and maternal verbal abuse

(15,

29–31). Measures that assessed parental affection toward the child, time spent with the child, and communication with the child were administered in the maternal and offspring interviews in 1983 and 1985–1986

(15,

29,

30). Interview items used to assess maternal punishment and offspring identification with the parents were administered during the maternal and offspring interviews in 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986

(29,

30). Parental home maintenance and maternal behavior during the interview were assessed on the basis of interviewers’ observations. Previous research has supported the construct validity of the measures that were used to assess parental behavior

(15,

16,

29–35). The scales and items assessing each type of parental behavior across the three interviews (1975, 1983, and 1985–1986) were dichotomized empirically at the maladaptive end of the scale to identify statistically deviant parental behaviors. To ensure adequate statistical power, parental behavior was defined as deviant if such behavior was at least one standard deviation from the sample mean.

Childhood maltreatment

Youths who had been referred to state agencies, investigated by childhood protective service agencies, and confirmed as being abused or neglected were identified from a central registry. Information about these individuals was abstracted from the registry by a member of the study team. Self-reports of childhood maltreatment were obtained from the offspring in 1991–1993. Official and self-reports were not available for offspring who were under age 18 in 1991–1993 or who had moved out of the state. Maternal interview items that were used to assess childhood neglect were obtained from the Disorganizing Poverty Interview on the basis of correspondence with the items in the cognitive, emotional, physical, and supervision neglect subscales of the Neglect Scale

(36). Childhood neglect was considered present if scores were ≥2 standard deviations above the sample mean and if there was clear evidence of parental neglect (e.g., failure to vaccinate the child).

Other childhood adversities and socioeconomic variables

The Disorganizing Poverty Interview was used to assess the following childhood adversities in 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986: death of a parent, disabling parental accident or illness, living in an unsafe neighborhood, low level of parental education, parental separation or divorce, peer aggression, low family income, school violence, the presence of a crime victim in the household, and upbringing by a single parent. Family income was transformed to percentage of the current U.S. poverty levels in 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986. Poverty was defined as mean income below 100% of the U.S. poverty levels. Low level of parental education was defined as less than a high school education for one or both parents. Adversities were considered present if reported at any of the three assessments. Numerous studies have supported the reliability and validity of the Disorganizing Poverty Interview

(15,

16).

Data Analytic Procedure

Analyses of contingency tables were conducted to investigate the associations between childhood adversities and eating or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood. An alpha level of 0.01 was adopted to reduce the likelihood of type I error. Logistic and multiple regression analyses were conducted to investigate whether these associations remained significant after the effects of age, difficult childhood temperament, eating problems during childhood, parental psychopathology, and co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate whether overall levels of maladaptive maternal and paternal behavior were associated with eating disorders in offspring during adolescence or early adulthood after the effects of co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to investigate whether the overall levels of maladaptive maternal and paternal behavior were associated with the total number of offspring problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood after the effects of co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

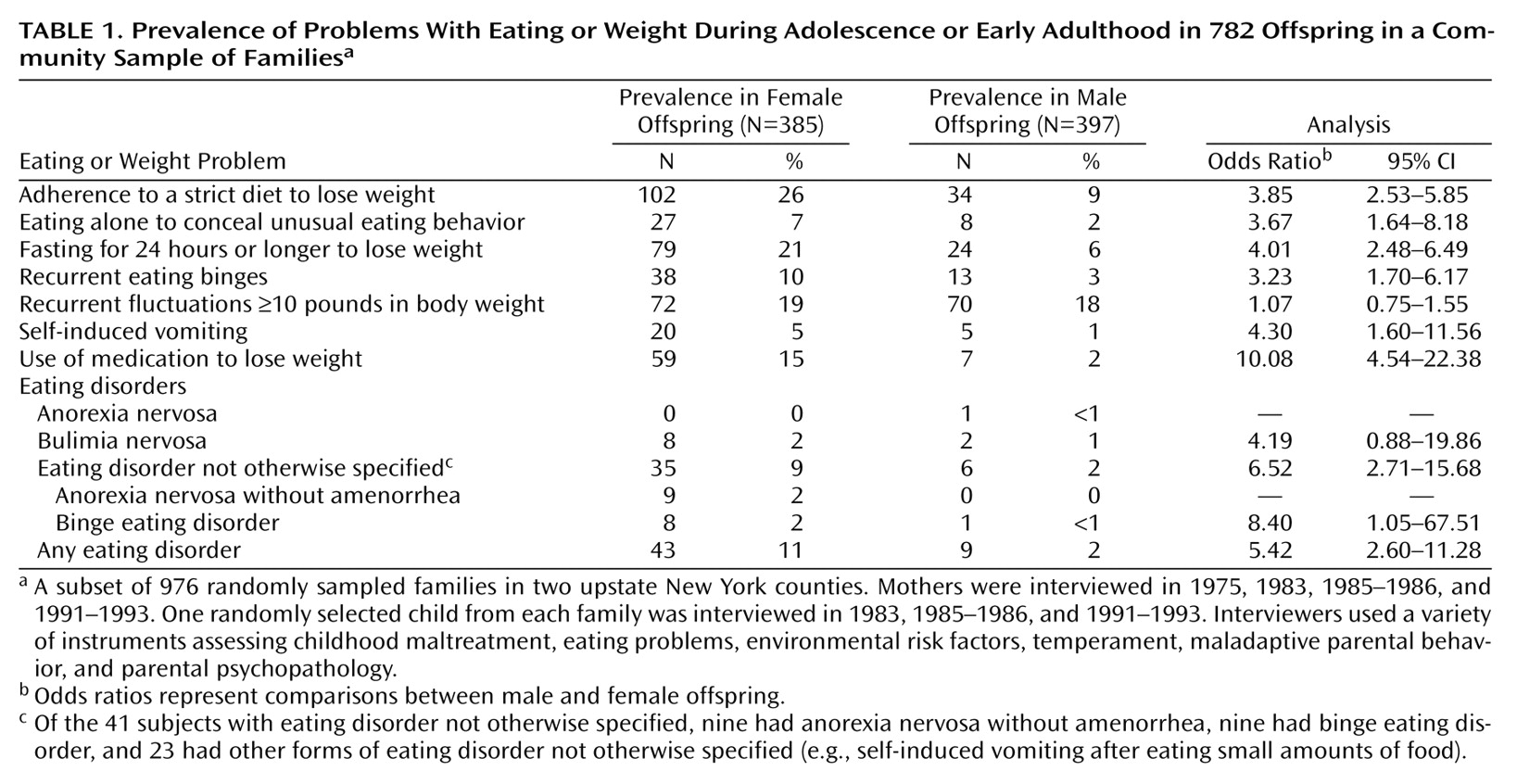

Fifty-two youths (6.6%) received a diagnosis of an eating disorder during adolescence or early adulthood. The frequencies of specific problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood are presented in

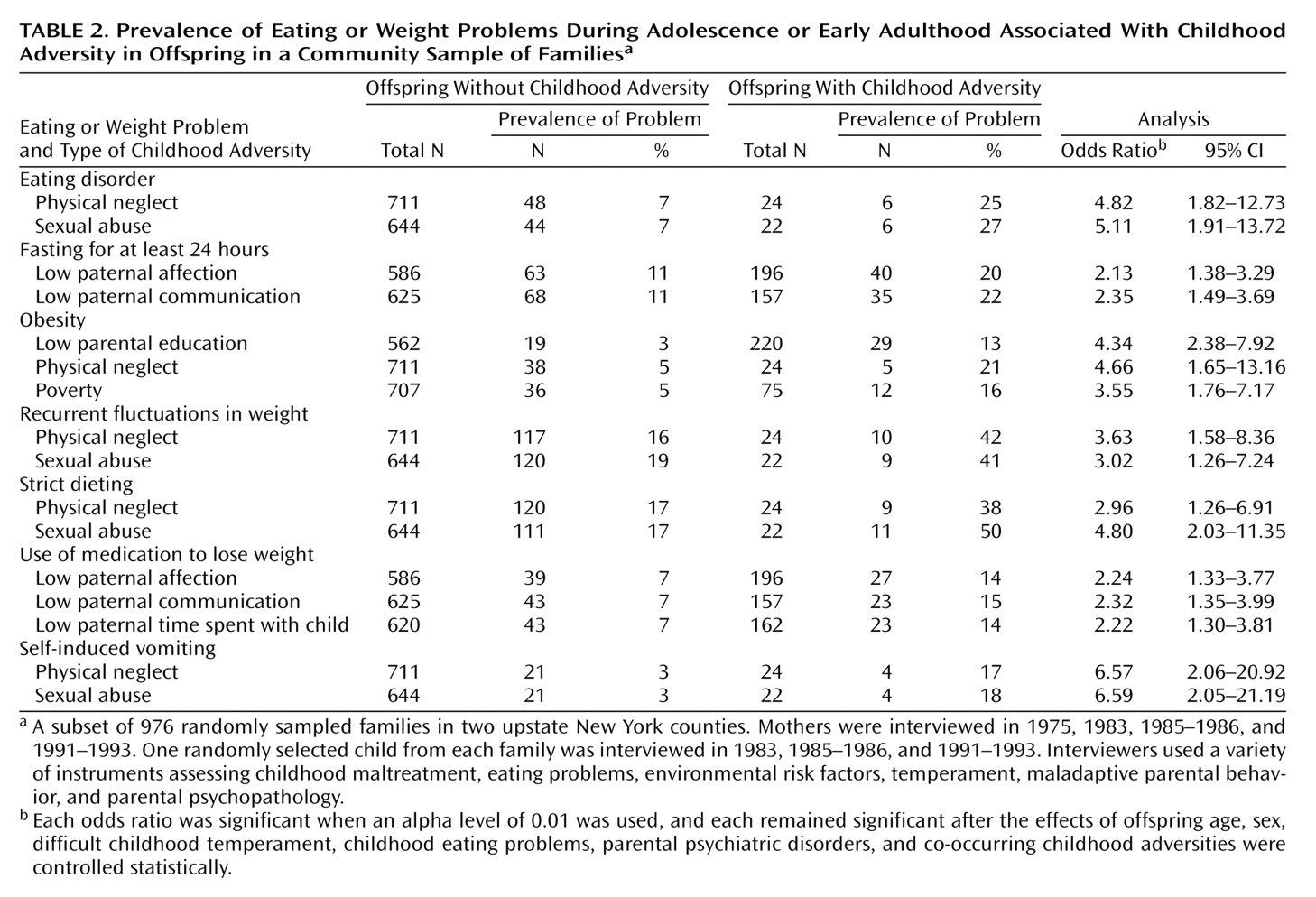

Table 1. The frequencies of childhood adversities that were uniquely associated with eating or weight problems are presented in

Table 2 and

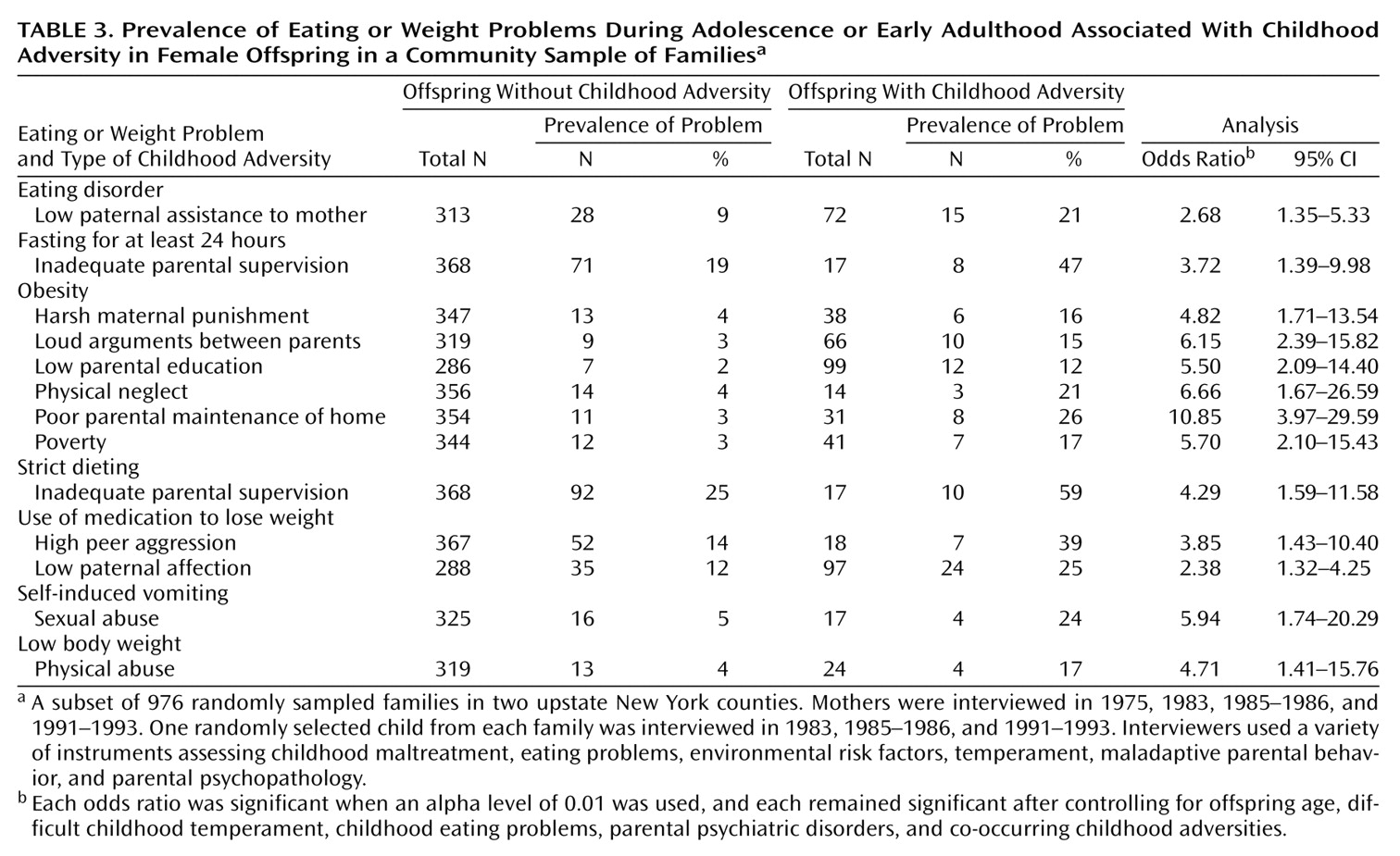

Table 3.

Childhood Adversities and Eating Disorders

Individuals who experienced physical neglect or sexual abuse during childhood were at elevated risk for eating disorders and for several types of eating or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood (

Table 2). Low paternal affection toward the child, low paternal communication with the child, low paternal time spent with the child, poverty, and low parental education were each associated with one or more types of eating or weight problems in the offspring during adolescence or early adulthood. These associations remained significant after the effects of age, difficult temperament, childhood eating problems, and parental psychiatric disorders were controlled statistically.

Because there was some temporal overlap between the assessment of childhood maltreatment and adolescent eating and weight problems, we also investigated the association between childhood adversities and problems with eating or weight during early adulthood. Low paternal time spent with the child (odds ratio=1.55, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.06–2.26), low paternal affection (odds ratio=1.78, 95% CI=1.24–2.53), sexual abuse (odds ratio=3.32, 95% CI=1.40–7.82), and physical neglect (odds ratio=4.58, 95% CI=1.99–10.46) were associated with elevated risk for problems with eating or weight during early adulthood. The index of maladaptive paternal behavior was associated with eating or weight problems during early adulthood (r=0.10, df=781, p=0.004). The index of maladaptive maternal behavior was not associated with eating or weight problems during early adulthood.

Maladaptive Maternal and Paternal Behavior

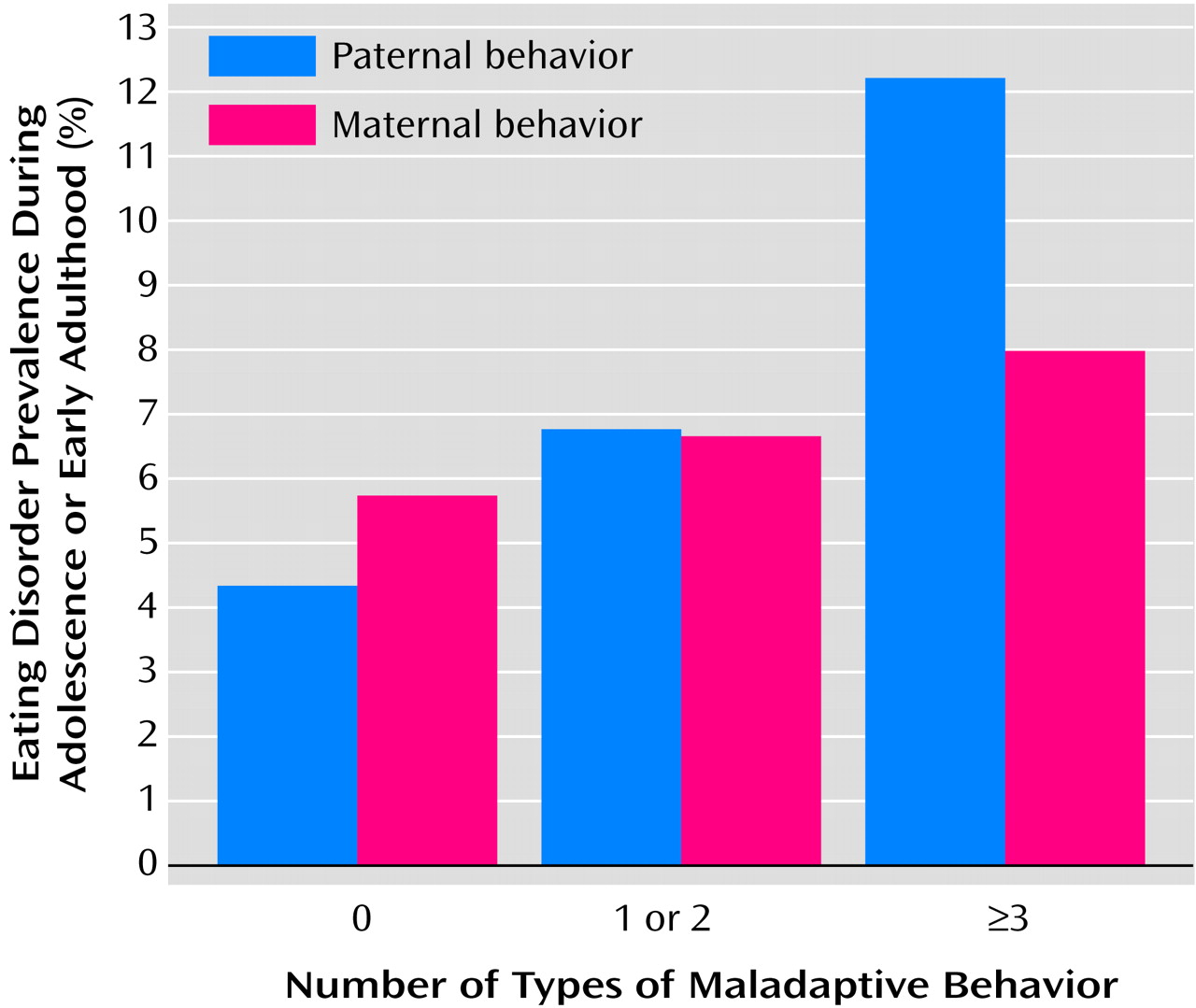

As

Figure 1 shows, youths who experienced three or more kinds of maladaptive paternal behavior were approximately three times as likely as youths who did not experience any maladaptive paternal behaviors to have eating disorders during adolescence or early adulthood (χ

2=9.49, df=2, p=0.009). The overall association between maladaptive maternal behavior and offspring risk for eating disorders was not statistically significant. The continuous index of maladaptive paternal behaviors remained significantly associated with offspring risk for eating disorders after the effects of co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled statistically.

The association between maladaptive paternal behaviors and offspring eating disorders was partly mediated by low offspring identification with the father. Youths who did not identify with their father were at elevated risk for eating disorders after the effect of maladaptive paternal behavior was controlled statistically (adjusted odds ratio=2.70, 95% CI=1.12–6.49). The association between maladaptive paternal behavior and offspring eating disorders did not remain significant after the effect of low offspring identification with the father was controlled statistically.

The index of maladaptive paternal behaviors was significantly correlated with the total number of eating or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood among the male (r=0.12, df=396, p=0.01) and female (r=0.10, df=384, p=0.04) offspring. The index of maladaptive maternal behaviors was not significantly correlated with the total number of eating or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood in either subsample. This pattern of findings was obtained regardless of whether the mother or the youth provided the data regarding parental behavior. Maladaptive paternal behaviors remained significantly associated with the total number of offspring problems with eating or weight after the effects of co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled statistically (t=2.89, df=777, p=0.004).

The indices of maladaptive maternal behaviors, types of childhood maltreatment, and other childhood adversities and socioeconomic variables were not independently associated with offspring risk for eating disorders after the effects of co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled statistically. However, the index of types of childhood maltreatment was independently associated with strict dieting (odds ratio=1.60, 95% CI=1.16–2.20), recurrent fluctuations in weight (odds ratio=1.58, 95% CI=1.15–2.16), and vomiting (odds ratio=1.89, 95% CI=1.08–3.29), and the index of other adversities was independently associated with obesity during adolescence or early adulthood (odds ratio=1.23, 95% CI=1.06–1.43).

Eating Problems Among Male and Female Offspring

Significant associations between childhood adversities and problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood among the female offspring are presented in

Table 3. The effects of the covariates were controlled. In the male subsample, low parental education was associated with elevated risk for obesity (odds ratio=3.60, 95% CI=1.66–7.79), and physical neglect during childhood was associated with elevated risk for use of medication to lose weight (odds ratio=17.50, 95% CI=2.94–104.12) and self-induced vomiting (odds ratio=29.33, 95% CI=4.29–200.39) during adolescence or early adulthood. These associations remained significant after Fisher’s exact tests were conducted and after the effects of the covariates were controlled statistically.

Discussion

The present findings advance our understanding of the association between childhood adversities and risk for eating disorders in several respects. First, our findings indicate that a wide range of childhood adversities tend to be associated with elevated risk for problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood after the effects of childhood eating problems, difficult childhood temperament, parental psychopathology, and co-occurring childhood adversities are controlled statistically. Further, the findings suggest that there may be unique associations between specific childhood adversities and specific problems with eating or weight and that there may be different patterns of association between adversities and problems with eating or weight among males and females in the general population.

The present findings suggest that maladaptive paternal behavior may play a more important role than maladaptive maternal behavior in the development of eating disorders in offspring. Most of the theoretical literature in this area has focused on the mother-child relationship

(37–

41). However, our findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that low paternal affection

(8), care

(9), and empathy

(12) and high paternal control

(8), unfriendliness

(14), overprotectiveness

(11), and seductiveness

(10) are associated with the development of eating disorders in offspring. Although the fathers were not interviewed in the present study, the findings are not likely to be attributable to reporting bias on the part of the informants. First, the overall rate of maladaptive paternal behavior was not higher than that of maladaptive maternal behavior. Second, the same pattern of findings was obtained with data for paternal behavior that were obtained during the maternal and offspring interviews. Third, maladaptive paternal behavior was not more strongly associated with offspring risk for other psychiatric disorders than was maladaptive maternal behavior

(34). Our findings also suggest that low paternal identification may partially mediate the association between maladaptive paternal behavior and eating disorders in offspring. It will be of interest for future research to further investigate the mechanisms that underlie this association.

The present findings are consistent with previous cross-sectional research suggesting that childhood maltreatment

(1–

3) and maladaptive parental behavior

(8–

13,

42) may contribute to the development of eating disorders and that many types of childhood adversities may be associated with risk for problems with eating or weight

(4–

7,

43). Because the present findings are based on prospective longitudinal data, they provide more compelling support for these hypotheses. Moreover, our findings support the hypothesis that the causes of eating disorders tend to be heterogeneous and multifactorial

(44). However, because previous research has provided inconsistent findings about the nature of the association between childhood adversities and the development of weight problems, it will be important for future research to investigate this association more extensively.

The limitations of the present study merit consideration. There were not enough cases to permit analyses of the relationships between childhood adversities and specific eating disorders. Therefore, we have reported associations between childhood adversities and several different types of eating and weight problems. To have enough statistical power to conduct separate analyses with the female and male subsamples, data on eating and weight problems during adolescence and early adulthood were pooled, and there was some overlap in the periods during which some of the risk factors and outcomes were assessed. To address this concern, we have reported associations between childhood adversities and problems with eating or weight during early adulthood. Despite these limitations, the present findings provide a detailed, systematic, and methodologically rigorous contribution to the literature.