It has long been recognized that the clinical manifestation of acute mania is characterized by more than pure manic features such as euphoria, grandiosity, flight of ideas, and increased drive. Atypical manic features such as depression, anxiety, irritable aggression, and psychosis have sometimes been described as occurring with pure manic features and are prominent in some patients with mania. Robertson

(1) proposed two varieties of acute mania: hilarious mania and furious or raging mania. Kraepelin

(2) described six mixed states: depressive or anxious mania, excited depression, mania with poverty of thought, manic stupor, depression with flight of ideas, and inhibited mania. Some of Kraepelin’s mixed states could be diagnosed as mania even according to current international diagnostic criteria such as DSM-IV or ICD-10.

Several empirical studies attempted to address such atypical manic features. On the basis of a factor analysis of manic symptoms in 12 (and later 30) manic patients, Beigel and Murphy

(3,

4) proposed two distinct manic subtypes: the elated-grandiose type, characterized by pure manic manifestations, and the destructive-paranoid type, characterized by atypical features such as aggression, psychosis, and dysphoria. Another factor analysis provided some evidence supporting this typology in 81 manic patients

(5). Although the typology has been accepted by consensus among psychiatric researchers for a long time, the small study group and the relatively narrow range of psychiatric symptoms included limit the validity of both factor analyses

(6). In fact, many studies reported findings contradictory to the typology.

Several authors found that atypical manic features could coexist (or be significantly correlated) in some patients with mania, particularly those experiencing a severely manic phase

(7–

9). However, these studies also provided evidence that depression was not always linked to aggression or psychosis in the longitudinal course of a manic episode

(8,

9). Some studies reported that manic patients with depressive symptoms (mixed manic states) did not have a higher incidence of psychosis than patients with pure mania

(10–

12).

Two studies

(6,

13) conducted factor analyses for manic symptoms including a broader range of atypical features. Dilsaver et al.

(13) analyzed 30 psychiatric symptoms of 105 manic patients. Although the number of subjects in the study was not so large as usually required for a reliable factor analysis

(14), the study found four independent factors: depression, sleep disturbance, mania, and irritability (aggression) with psychosis. Cassidy et al.

(6) described the first factor analysis with a sufficiently large study group in this field. This study extracted five uncorrelated factors: dysphoria (depression), psychomotor acceleration, psychosis, increased hedonic function, and irritable aggression. Both studies indicated that atypical manic features such as depression, aggression, and psychosis are composed of several independent syndromes.

In the present study we conducted a factor analysis of 37 psychiatric symptoms systematically assessed among 576 inpatients with acute mania. The large study group allowed for including a broad range of psychiatric symptoms for the analysis. To our knowledge, this analysis is the first to include symptoms representative of depressive inhibition. Kraepelin

(2) suggested several mixed manic states with psychomotor or thought inhibition—inhibited mania, mania with poverty of thought, and manic stupor. Depressive inhibition, however, has rarely been well examined in empirical studies exploring atypical manic features.

Method

Patients

All patients who were hospitalized for any affective disorder at the Psychiatric Hospital of the Ludwig-Maximilian University in Munich during the period 1980 to 1997 were considered as subjects in this study. Routine clinical diagnoses of these patients were made according to ICD-9 or ICD-10, and a broad range of 196 psychiatric and related somatic symptoms were systematically evaluated for all patients at both admission and discharge as part of the routine documentation at the hospital. These symptoms were assessed by using a standardized instrument that allowed for precise diagnoses of DSM-IV manic episodes, nonmixed and mixed.

The following inclusion criteria were used: 1) patients had to be diagnosed according to the ICD system as currently having a manic or mixed episode (ICD-9 diagnoses 296.0, 296.2, or 296.4 or ICD-10 diagnoses F30, F31.0, F31.1, F31.2, F31.6, or F38.00); 2) patients had to be younger than 70 years; and 3) patients had to meet DSM-IV criteria for a manic episode, nonmixed or mixed. If a patient experienced more than one hospitalization during the study period, only data for the last admission were included.

The final study group included in the analyses consisted of 576 consecutive inpatients with DSM-IV manic episode, nonmixed or mixed. Of these subjects, 292 (51%) were women and 284 (49%) were men. Their mean age was 38.6 years (SD=12.6). Their mean age at onset of first affective episode was 28.9 years (SD=10.7). Fifty-eight patients (10%) (38 women and 20 men) met criteria for DSM-IV manic episode, mixed. The patients were treated with medications as clinically appropriate during their hospital stay.

Clinical Assessments

The Association for Methodology and Documentation in Psychiatry system

(15) was used to assess psychiatric symptoms. This system consists of a comprehensive rating instrument developed on the basis of German traditional descriptive psychopathology of functional psychoses and is used in most psychiatric institutes in German-speaking countries. Each psychiatric symptom of the Association for Methodology and Documentation in Psychiatry system is scored from 0 (absent) to 3 (severe) with defined anchor statements by administration of a semistructured interview. Several studies indicated moderate to high interrater agreements for most of the symptoms included in the system

(16). The Global Assessment of Functioning scale (in DSM-R-III) was also administered to all subjects at discharge. All subjects gave written informed consent to being assessed with the instruments.

Trained ward-attending psychiatrists administered the two instruments. The assessments at admission were made during the first 1 to 5 days of the hospital stay, and the discharge assessment was done on the day of discharge. Among the psychiatric symptoms assessed, 37 symptoms were selected because they were judged related to manic manifestations on the basis of a careful review of the literature. Some symptoms representative of depressive thought and psychomotor inhibition (retarded thought, inhibited thought, psychomotor inhibition, and inhibited drive) were included because Kraepelin

(2) described several mixed subtypes in which psychomotor or thought inhibition coexists with manic euphoria.

Interrater reliability was explored for the 37 symptoms by having three raters using the Association for Methodology and Documentation in Psychiatry system independently assess 28 patients with mania of differing severity. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) intraclass correlation coefficients

(17) were equal to or higher than 0.61 for the majority of the symptoms and lower than 0.61 for motor restlessness (0.58), impatience (0.56), and distractibility (0.55), indicating substantial or moderate interrater reliability of the symptoms included.

The patients’ scores for the 37 symptoms at admission were used in the following factor analysis. The number of symptoms that were still scored higher than 1 at discharge was calculated to construct an outcome measure (number of residual symptoms at discharge). Suicidality at admission was defined in this study as a score on the Association for Methodology and Documentation in Psychiatry suicide item higher than 1 (mild: “the patient repeatedly expresses the feeling that her/his life has no meaning”).

Statistical Analyses

A principal-component analysis followed by varimax rotation was conducted for the 37 psychiatric symptoms at admission. Distributions of standardized factor scores were tested for normality by using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis, with each factor considered orthogonal, was used to estimate the overall model fit and the stability of the obtained factor structure across several subject groups. Several fit indexes such as the goodness-of-fit index, the adjusted goodness-of-fit index, and the root mean square error of approximation were applied. The goodness-of-fit index ranges from 0 to unity, and a value greater than 0.9 indicates a good fit

(18). The adjusted goodness-of-fit index ranges from 0 to unity, and a value greater than 0.8 indicates an acceptable fit

(19,

20). An root mean square error of approximation value smaller than 0.05 is generally considered a good fit

(21).

The computed factor scores were then analyzed by cluster analysis, with the squared Euclidean method for calculating proximities and Ward’s method for agglomeration, in order to ascertain several phenomenological subtypes. The obtained subtypes were compared in terms of mean factor scores as well as several demographic and clinical variables. Overall multivariate comparisons of these variables among the subgroups were made by using a multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) for the factor scores and a multivariate linear discriminant function analysis for the demographic and clinical variables.

Post hoc univariate tests were performed with chi-square tests for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis tests or ANOVA for continuous variables according to whether the statistical assumptions required for ANOVA were violated. The significance level for each univariate test was adjusted by using Bonferroni’s method. Significant differences produced by chi-square test and Kruskal-Wallis test were followed by Dunn’s test

(22), and significant differences produced by ANOVA were followed by Scheffé’s test. Probability statements are two-tailed. Statistical analyses were conducted by using Amos 3.6

(23) and SPSS 7.0

(24).

Results

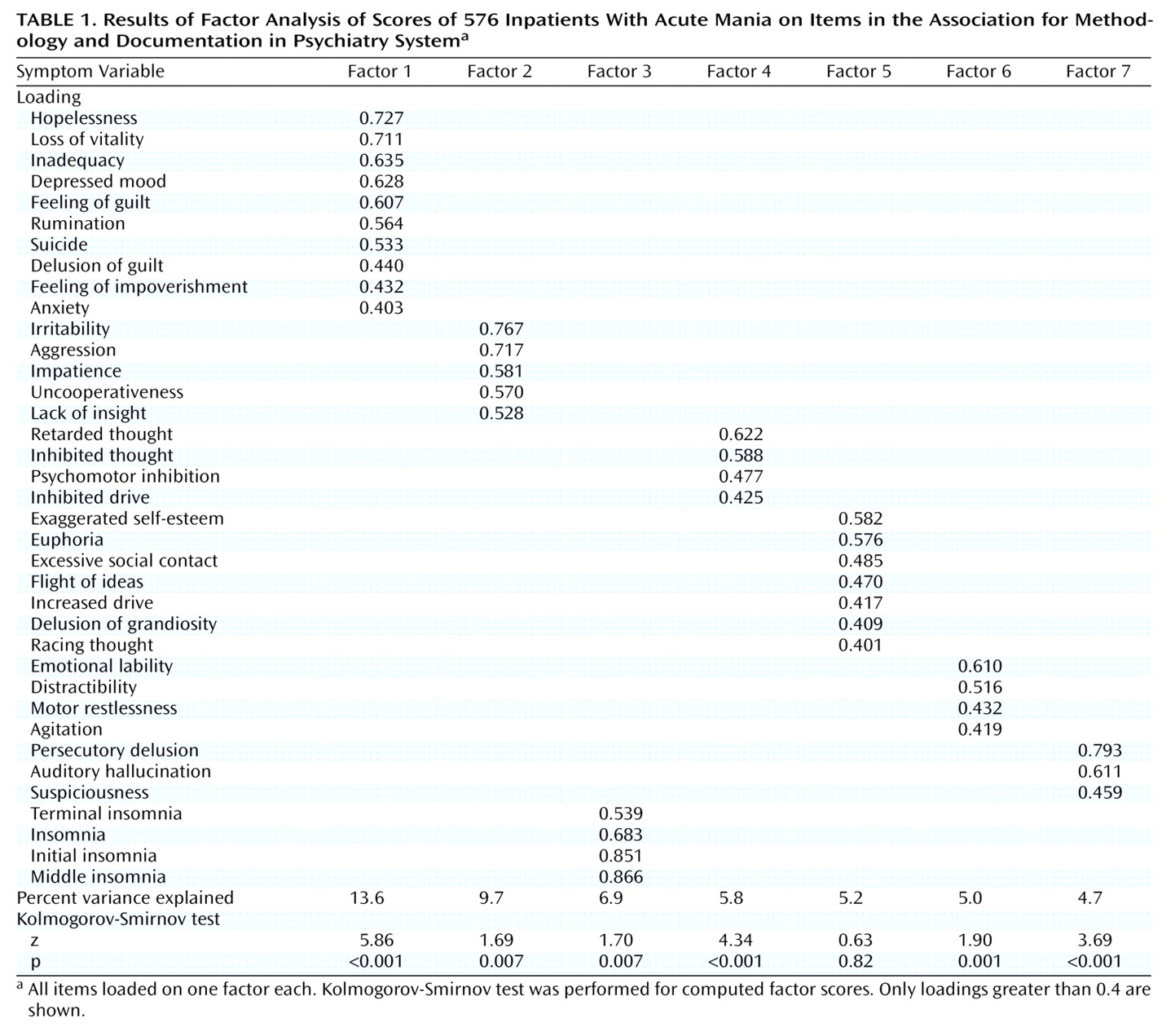

The principal-component analysis produced 10 eigenvalues greater than unity. However, scree-test and parallel analysis

(25) indicated that a seven-factor solution was more appropriate to extract interpretable factors; therefore, we chose a seven-factor solution. The seven factors explained 50.9% of the total variance. Rotated factor loadings greater than 0.4 and percent variance explained by each extracted factor are shown in

Table 1. All symptoms loaded on only one factor each.

The first factor, depressed mood, isolated 10 depressive symptoms other than psychomotor or thought inhibition. The second factor, irritable aggression, had high loadings of irritability, aggression, impatience, uncooperativeness, and lack of insight. On the third factor, sleep disturbance, symptoms related to insomnia had high loadings. The fourth factor, psychomotor/thought inhibition, isolated four symptoms related to depressive inhibition. For the fifth factor, mania, seven manic symptoms (exaggerated self-esteem, euphoria, excessive social contact, flight of ideas, increased drive, delusion of grandiosity, racing thoughts) had high loadings. The sixth factor was emotional lability/agitation, and the seventh, psychosis, had high loadings for psychotic symptoms. No standardized factor score showed a bimodal distribution. Only the score on factor 5 had normal distribution according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (

Table 1).

The model fit of the factor structure was estimated by using confirmatory factor analysis for all patients (N=576) and for patients with DSM-IV nonmixed manic episode only (N=518). The hypothesis that the factor structure is invariant across female and male subjects and across younger (younger than 40 years: N=333) and older (40 years or older: N=243) subjects was also tested. The fit indexes for the factor structure were in a range suggestive of an acceptable or good fit for all subjects (goodness-of-fit index=0.880, adjusted goodness-of-fit index=0.861, and root mean square error of approximation=0.048) and for subjects with DSM-IV nonmixed manic episode only (goodness-of-fit index=0.877, adjusted goodness-of-fit index=0.858, and root mean square error of approximation=0.047). The fit indexes for the hypothesis of invariance of the factor structure across female and male subjects (goodness-of-fit index=0.831, adjusted goodness-of-fit index=0.813, and root mean square error of approximation=0.039) and across younger and older subjects (goodness-of-fit index=0.829, adjusted goodness-of-fit index=0.811, and root mean square error of approximation=0.039) also remained in a similar range, indicating that the hypothesis was statistically supported.

The cluster analysis used the seven standardized factor scores computed by the factor analysis. Coefficients for each step of agglomeration indicated that a four-group solution was most appropriate when using the elbow criteria

(26) (i.e., plotted coefficients by number of clusters were making a turn at number of clusters=4).

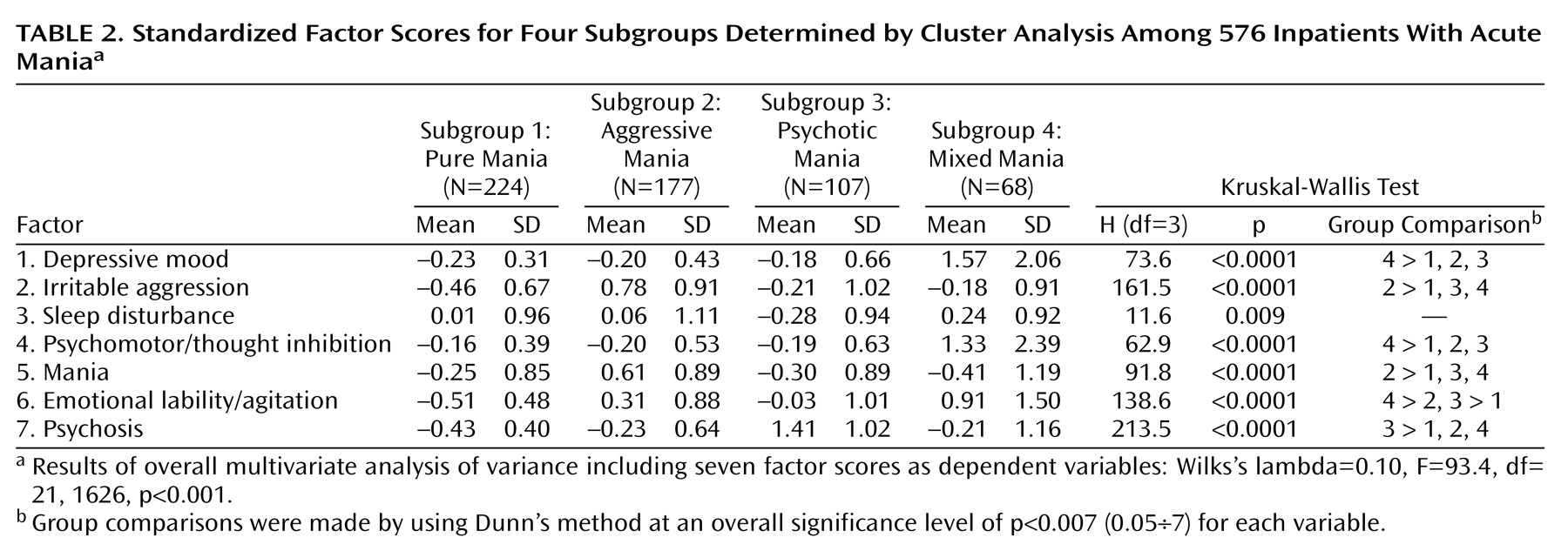

Symptom profiles of the four groups are shown in

Table 2. Overall MANOVA produced a significant F value (

Table 2). Post hoc univariate tests using Kruskal-Wallis test revealed distinct symptomatic features characterizing the identified four groups: irritable aggression and mania were prominent in subgroup 2; psychosis was outstanding in subgroup 3; and depressive mood and psychomotor/thought inhibition characterized subgroup 4. Emotional lability/agitation was significant in the subgroups 2, 3, and 4, particularly in subgroup 4. The data in

Table 2 indicate that subgroups 1, 2, 3, and 4 represented pure mania, aggressive mania, psychotic mania, and depressive (mixed) mania, respectively.

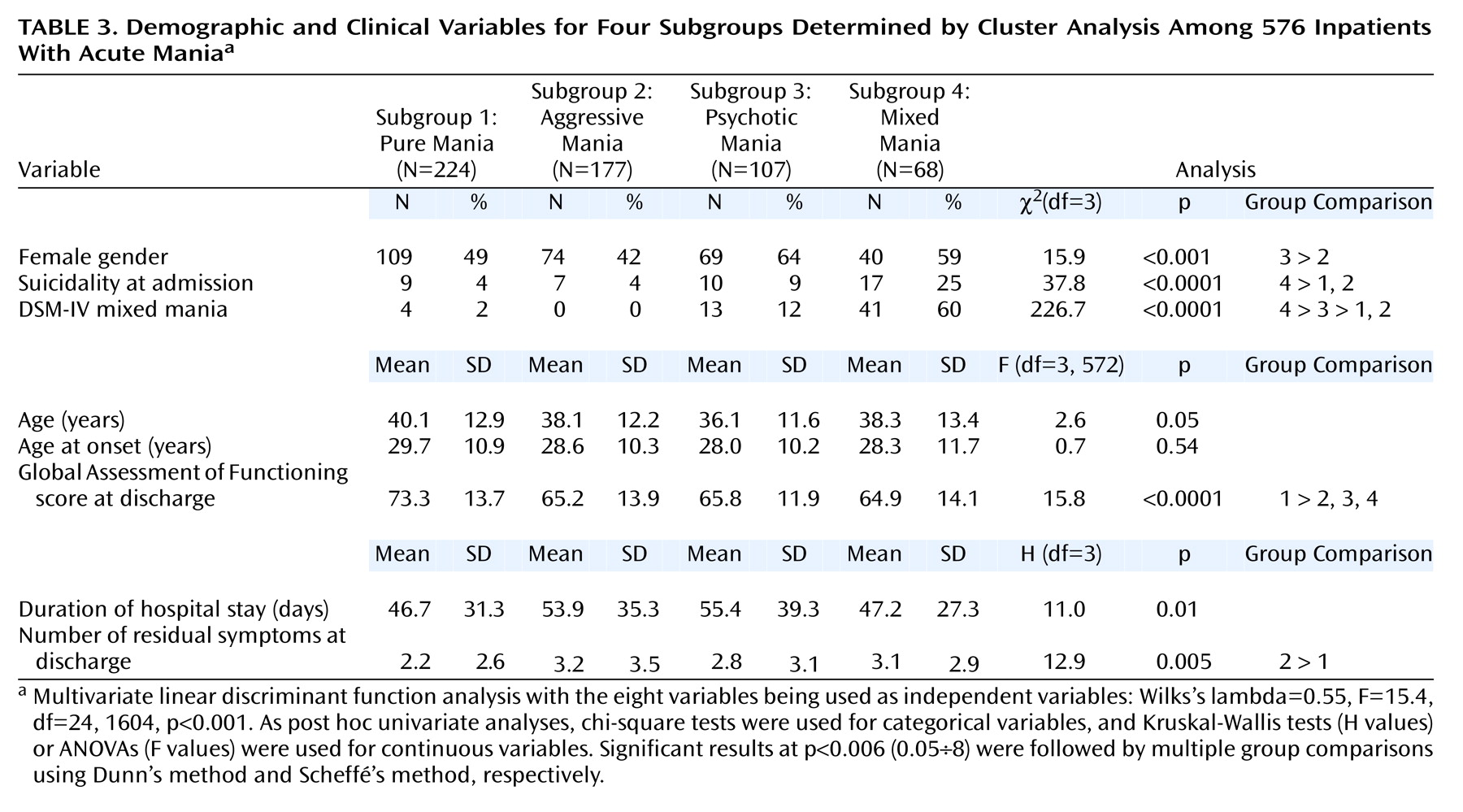

Several demographic and clinical variables were compared among the identified subgroups (

Table 3). An overall group comparison using linear discriminant function analysis produced a significant F value (

Table 3), indicating that the examined variables significantly differed among the four groups. Post hoc univariate tests revealed that the four identified subgroups were significantly distinguishable in terms of gender, suicidality at admission, diagnoses of DSM-IV mixed mania, Global Assessment of Functioning score at discharge, and number of residual symptoms at discharge.

In particular, the mixed mania subgroup appeared to have clinical features similar to those suggested by many previous validation studies

(9–

11,

27–32). The mixed mania subgroup had a significantly higher frequency of suicidality, was more likely to meet criteria for DSM-IV mixed manic episode, and had a worse social adjustment at discharge than the pure mania subgroup.

Gender was not significantly different between the pure mania and the mixed mania subgroups, but there were somewhat more women in the mixed mania subgroup than in the pure and aggressive mania subgroups combined (χ2=3.54 with continuity correction, df=1, p=0.06). The number of residual symptoms tended to be higher in the mixed mania subgroup than in the pure mania subgroup (Mann-Whitney U=6087, z=2.56, p=0.001).

Confidence intervals of differences in mean or proportion, calculated at an adjusted significance level (Bonferroni correction), showed the same results for all individual group comparisons presented in the tables: i.e., all confidence intervals for significant contrasts did not include 0, but all confidence intervals for nonsignificant contrasts included 0. However, some differences in mean or proportion (for example, difference in mean number of residual symptoms) are not large, which would require caution in interpreting clinical significance of these data.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest factor analytic study of manic patients that examined a broad range of 37 psychiatric symptoms. Psychiatric symptoms related to depressive inhibition, which Kraepelin

(2) described as being distinguishing features for several mixed mania subtypes, were included in the analysis, together with other psychiatric features related to different manic manifestations. The analysis isolated seven independent factors that appeared to be relatively stable across several patient groups, as shown by confirmatory factor analyses. These factors were depressive mood, irritable aggression, sleep disturbance, psychomotor/thought inhibition, pure mania, emotional lability/agitation, and psychosis. Consistent with the findings of similar studies

(6,

13), depressive mood was extracted as the first factor, indicating that depressive mood is salient in patients with acute mania.

Symptoms related to depressive inhibition were also identified as an independent factor; this indicates that these symptoms constitute a considerable syndrome among manic patients and that manic patients do not necessarily exhibit hyperactivity, increased drive, or racing thoughts. The factor was isolated separately from depressive mood, suggesting that depressive inhibition and depressive mood occur separately rather than simultaneously with other manic symptoms among these patients. These findings appear to lend some support to Kraepelin’s classification of mixed states on the basis of the permutations of three elements—thought disorder, mood, and psychomotor activity

(2). Although Kraepelin described three mixed subtypes with depressive inhibition, this syndrome appears to have been of little or no interest among researchers examining mixed affective states. Only one previous study

(33) provided evidence that depressive inhibition is not negligible among patients with mixed mania. This study found that the score for this syndrome in patients with mixed mania was as high as it was in patients with agitated depression and significantly higher than it was in patients with pure mania. Our results confirm these observations. Data presented in

Table 2 suggest that depressive inhibition, together with depressive mood and emotional lability/agitation, is one of the salient psychiatric syndromes of mixed mania. The specificity and sensitivity of depressive inhibition in diagnosing mixed affective states should be studied further.

Several studies conducted a factor analysis for manic symptoms including atypical features

(3–

6,

13). Unfortunately, most of these studies had an insufficient number of subjects compared with the number of symptoms included

(14). The only study free from this limitation is that by Cassidy et al.

(6), who isolated five independent factors for 20 psychiatric symptoms. The similarity in results between our study and the study of Cassidy et al. is that atypical features such as depressive mood, irritable aggression, and psychosis loaded on separate uncorrelated factors. This agreement strongly suggests that these three syndromes are unlikely to coexist but likely to constitute three relatively separate syndromes among manic patients. A notable dissimilarity is that our study identified one factor for pure mania but Cassidy et al.

(6) isolated two factors for similar symptoms. This may be explained by the fact that our study included a broader range of psychiatric symptoms. Symptoms such as depressive inhibition or agitation were not included in their analysis. The dissimilarity may suggest that the possible diversity of pure manic symptoms among manic patients, as shown in their study, is not significant when a broader range of psychiatric symptoms is considered.

The statistical procedure of cluster analysis in the present study also indicated that depressive mood, irritable aggression, and psychosis are not likely to coexist in manic patients. In addition to the pure mania subtype, there appear to be three phenomenological subtypes of acute mania in which depressive mood, irritable aggression, or psychosis is separately prominent. The depressive (mixed) subtype was also characterized by psychomotor/thought inhibition and emotional lability/agitation. The irritable aggressive subtype showed a higher level of pure mania than did the other three subtypes. Emotional lability/agitation was significant in the three subtypes other than pure mania. Of interest, the identified phenomenological subtypes were statistically distinguishable in terms of several demographic and clinical variables, some of which (i.e., gender, suicidality, and outcome of treatments) had been suggested by many previous studies to have the potential to validate manic subtypes

(9–

11,

27–32). This suggests that the identified four subtypes are not merely a phenomenological classification of acute mania but also reflect clinically meaningful subtypes underlying acute mania.

A recent cluster analysis study by Dilsaver et al.

(13) proposed three manic phenomenological presentations (euphoric, dysphoric, and depressive). Their euphoric mania closely resembles our pure mania subtype. Consistent with our results, their study suggested that there are several different manic presentations besides pure mania. The symptom profile of the other two subtypes were, however, greatly different from our subtypes. The major origin of these differences may be that their fourth factor, irritability and paranoia, was split into two factors in our factor analysis. A sufficiently large study group and a broader range of psychiatric symptoms may have resulted in a more precise classification of manic patients in our cluster analysis.

The identified factors and subtypes can be a useful conceptualization of atypical features among patients with acute mania. These features appear to have sometimes been considered as one psychiatric syndrome, which may have led previous researchers into overlooking potentially important findings. The conceptualization provided here may allow for identifying or detecting a finding related to a more rational treatment strategy and a more reasonable conceptualization of biological substrates in manic patients. To determine whether the identified subtypes are really of clinical and theoretical importance, however, further validation studies exploring variables such as specific treatment responses (including responses to currently used and putative antimanic agents, family history, candidate biological substrates, and long-term course) are naturally required, although patients with variously defined mixed states were reported to differ from pure manic patients on some of these variables

(9–

11,

27–

32,

34–42). Using the subjects included in the present study, we are preparing to report differences in several clinically important variables among the identified subtypes.

Several limitations should be noted in interpreting the results of the present study. First, the psychiatric symptoms were assessed when the subjects were hospitalized. Some studies

(7,

8,

43) provided evidence that patients’ symptom profiles change greatly during a manic episode. It is therefore unclear whether the identified factors are constant for the whole period of a manic episode. Further study comparing the symptom factors at several different stages during a manic episode is needed. Second, most of the patients included in the study were referred to our hospital and were not medication-free when they were hospitalized; this may have affected the identified factors and subtypes. It is necessary to confirm the similarity in results between our subjects and medication-free subjects. It is notable, however, that most patients with mania are hospitalized and that hospitalized manic patients are rarely medication free; thus, our data may be useful in the most usual clinical settings for manic patients.