Our historical review suggests that the status of atypical depression is problematic. The distinct reference to personality style and anxiety in early descriptions, and the demonstration of MAOI benefits in certain anxiety disorders and in possibly modulating “hysteroid dysphoria,” suggest alternate hypotheses. We used an existing patient database to analyze properties of the DSM-IV criteria set, and we propose an alternate model in which atypical depression is shaped by personality style and/or expressions of anxiety.

Is the DSM-IV Definition Valid?

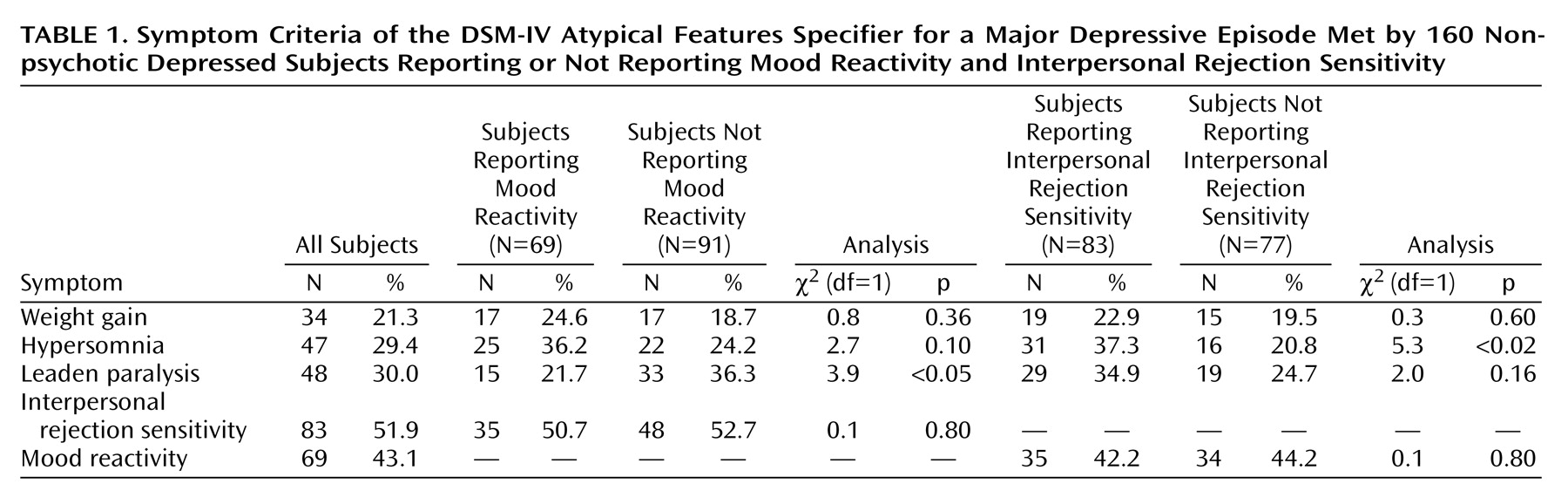

If the DSM-IV criteria for the atypical features specifier provide a valid definition of atypical depression, then accessory features should be overrepresented in depressed patients who have a reactive mood but do not have psychotic or melancholic depression. However, as

Table 1 shows, none of the DSM-IV criterion B features were significantly overrepresented in the nonmelancholic subjects who reported a reactive mood. The only significant finding was, paradoxically, that leaden paralysis was

less common. Nonsignificant findings could theoretically reflect insufficient power. The size of the study group, however, had sufficient power (80%) to detect differences of 20% versus 42% (or larger) and thus of an order appropriate for diagnostic significance.

It is possible that mood reactivity lost its relevance as a criterion by excluding those with psychotic or melancholic depression. Thus, chi-square analyses were repeated by using data from the overall study group of 270 patients, of whom 111 had mood reactivity and 159 did not. The distribution of associated features (respectively) for those with and without mood reactivity was 22.5% versus 18.5% (χ2=0.8, df=1, p=0.39) for weight gain, 30.6% versus 22.6% (χ2=2.2, df=1, p=0.14) for hypersomnia, 25.2% versus 34.6% (χ2=2.7, df=1, p=0.10) for leaden paralysis, and 42.3% versus 37.7% (χ2=0.6, df=1, p=0.45) for interpersonal rejection sensitivity.

Although associations between mood reactivity and individual criterion B accessory symptoms were weak, we nevertheless examined for associations between mood reactivity and salient covariates (i.e., gender, bipolar status, trichotomized age, Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton depression scale scores) in a group of 151 subjects after excluding all subjects with missing data. Logistic regression analyses examined the impact of each covariate alone on mood reactivity, with the only significant predictors being depression severity measures. Thus, with a Hamilton depression scale score of 17 or less as the reference category, those scoring 18 to 24 were less likely to report mood reactivity (odds ratio=0.31, Wald χ2=8.6, df=1, p=0.003), as were those scoring 25 or more (odds ratio=0.20, Wald χ2=11.3, df=1, p=0.001). Second, with a Beck Depression Inventory score of 21 or less as the reference category, those scoring 22 to 40 were less likely to report mood reactivity (odds ratio=0.42, Wald χ2=4.5, df=1, p=0.03), as were those scoring more than 40 (odds ratio=0.35, Wald χ2=3.5, df=1, p=0.06). When all five covariates were included, there was a significant overall improvement in prediction (change in χ2=20.2, df=8, p=0.01), but only the difference in Hamilton depression scale scores was significant (for Hamilton depression scale scores of 18–24: odds ratio=0.29, Wald χ2=7.7, df=1, p=0.005; for Hamilton depression scale scores of 25 or more: odds ratio=0.19, Wald χ2=9.4, df=1, p=0.002). Clearly, the more severe the depression the less likely it was for patients to report criterion A and thus be eligible for the diagnosis.

We then used Poisson regression to examine the effect of the five covariates and criterion A on the number of reported criterion B symptoms, which is critical to the diagnosis. All six analyses showed nonsignificant effects as did the multivariate regression analysis (χ2=9.8, df=9, p=0.37). Thus, the number of criterion B symptoms was largely unrelated to the covariates (including depression severity) or, and more importantly, to criterion A. These several analyses argued against the intrinsic validity of the DSM-IV decision rules, perhaps because the mandatory criterion of reactive mood is nondiscriminatory and is more a marker of depression severity.

If atypical depression is a spectrum disorder

(38,

39), then a personality style of interpersonal rejection sensitivity might determine overrepresented depressive symptoms. We thus compared data on the remaining atypical symptoms for subjects classified as either positive or negative for interpersonal rejection sensitivity (

Table 1). Those with interpersonal rejection sensitivity were significantly more likely to report hypersomnia and nonsignificantly more likely to report leaden paralysis, but rates of weight gain and mood reactivity were similar in the two groups.

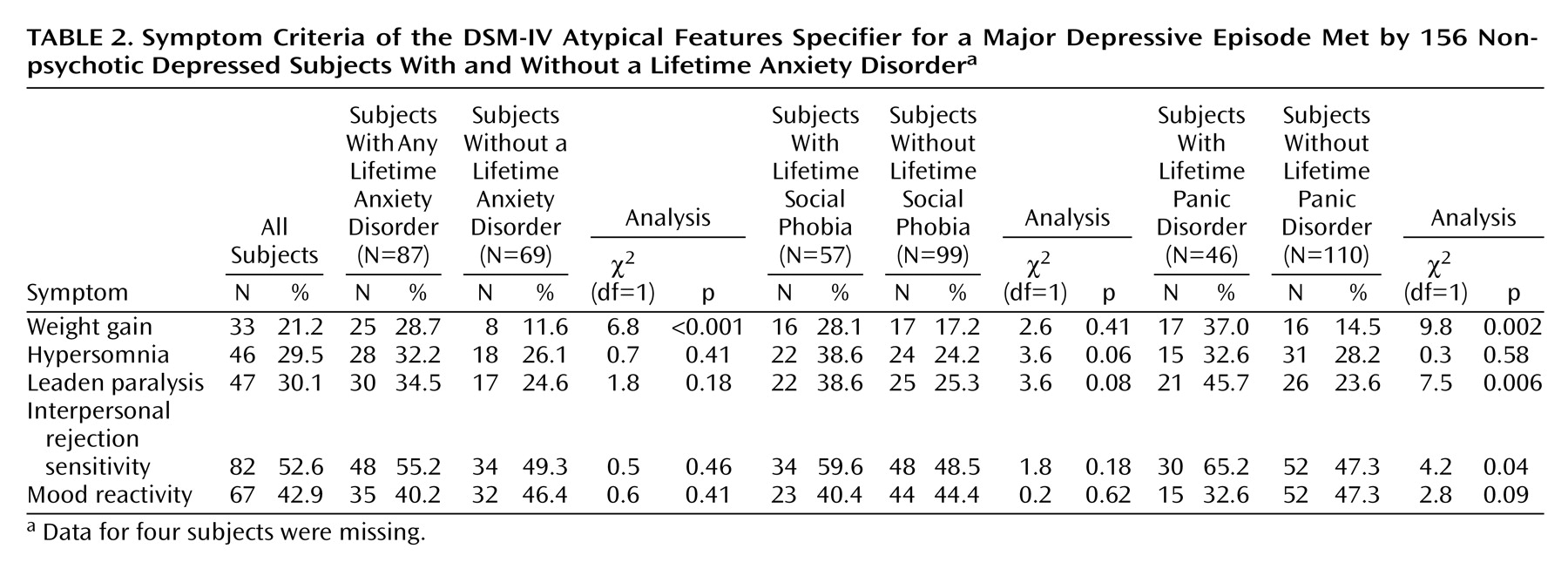

Respecting historical links between atypical features and anxiety disorders, we examined the extent to which the presence of a lifetime anxiety disorder (assessed by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview) increased the probability of DSM-IV features. Lifetime anxiety disorder included panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, agoraphobia, and social phobia, with prevalence estimates of 29%, 11%, 11%, 8%, and 36%, respectively.

Table 2 shows that those experiencing any lifetime anxiety disorder differed only in being more likely to report weight gain. A separate examination of the two most prevalent anxiety disorders (panic disorder and social phobia) identified several differences. Those meeting criteria for lifetime social phobia tended to be more likely to report hypersomnia and leaden paralysis, although the differences did not reach significance. Those meeting lifetime criteria for panic disorder were significantly more likely to report weight gain, leaden paralysis, and interpersonal rejection sensitivity.

Log linear analyses examined the effects of lifetime anxiety disorder diagnosis, gender, and their interaction on the reporting of atypical depressive symptoms. For panic disorder, there were significant main effects for diagnosis on weight gain (z=2.16, p=0.03, N=156), leaden paralysis (z=2.06, p=0.04, N=156), and interpersonal rejection sensitivity rejection (z=2.68, p<0.01, N=156), indicating increased symptom rates for those with panic disorder. An effect of gender was only significant for interpersonal rejection sensitivity (z=2.49, p<0.05, N=156), which was reported by 79.3% of the female subjects and 41.2% of the male subjects. There were no significant diagnosis-by-gender interactions. For social phobia, there was a significant main effect for leaden paralysis, both for diagnosis (z=2.56, p<0.05, N=156) and for gender (z=2.65, p<0.01, N=156). Leaden paralysis was reported by 52.8% of female subjects and 14.3% of male subjects.

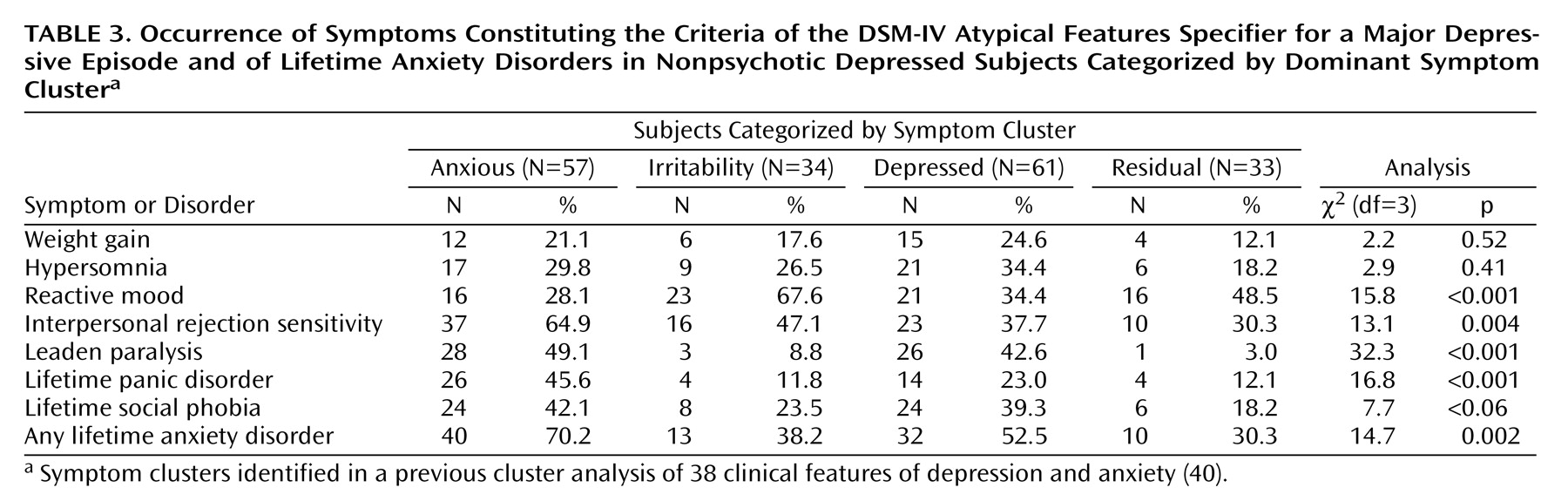

In a previous study

(40) we refined a set of 61 clinical features of anxiety and depression to form a group of 38 clinical features (21 depression features and 17 anxiety features) and conducted cluster analyses to identify a four-cluster solution with clusters labeled anxiety, irritability, depressed mood, and residual. Here we examine the prevalence of the symptoms that constitute the DSM-IV criteria for the atypical features specifier and the prevalence of relevant lifetime anxiety disorders across the four clusters (

Table 3). As might be anticipated, lifetime anxiety disorder as well as lifetime panic disorder (separately) loaded highest on the anxiety cluster, together with two of the associated atypical symptoms (interpersonal sensitivity rejection and leaden paralysis). Mood reactivity rates differed significantly across the clusters, having the lowest prevalence in the anxiety cluster and the highest in the irritability cluster. Weight gain and hypersomnia rates did not differ significantly across clusters. The analysis suggests differing levels of specificity in the phenomenological roots of the atypical features.

Poisson regression analyses were undertaken for the three anxiety disorder variables listed in

Table 3 to examine the effect when the variable was entered alone and then after all other covariates. The data set comprised 147 subjects to ensure that there were no missing data. The effect of any lifetime anxiety disorder (when entered alone) corresponded to having 1.32 as many symptoms, a nonsignificant effect (χ

2=3.63, df=1, p=0.06), which remained nonsignificant (p=0.08) when the variable was entered last. When lifetime panic disorder was entered alone, the effect was equal to 1.57 times as many symptoms and was significant (χ

2=8.72, df=1, p=0.003). Panic disorder remained significant when added last, and the effect was equal to 1.60 times as many symptoms (χ

2=8.50, df=1, p=0.004). For social phobia entered alone, the effect was significant and corresponded to 1.47 times as many symptoms (χ

2=7.06, df=1, p=0.008); adding social phobia last gave a significant effect equal to 1.41 times as many symptoms (χ

2=5.21, df=1, p=0.02). These analyses indicate that elements of panic disorder/social phobia make up the key driver of the number of criterion B symptoms, which determines whether the DSM-IV atypical features specifier can be applied for depressed individuals who meet criterion A.