The behavioral and pharmacological effects of the noncompetitive

N-methyl-

d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist ketamine have been used to study important aspects of psychotomimetic action in humans

(1). Several lines of evidence support the use of ketamine as a pharmacological model of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia patients administered subanesthetic doses of ketamine experience a brief exacerbation of positive, cognitive, and possibly negative symptoms

(2,

3). Ketamine also appears to provoke psychotic symptoms specific to a patient’s disease history

(2). Imaging studies

(4–

8) have shown that ketamine changes the neuronal activity in areas thought to be involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, including the medial frontal and anterior cingulate cortex, the hippocampus, and the cerebellum. Other studies have shown that ketamine causes schizophrenia-like positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms in normal healthy volunteers

(9–

14), including deficits in sensory processing

(15) and eye-tracking performance

(16,

17). Together, these data suggest that glutamatergic neurotransmission mediated by the NMDA receptor is involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia

(18).

The presence of eye-tracking abnormalities among schizophrenia patients and their biological relatives has been reported by numerous investigators examining smooth-pursuit and saccadic eye-movement measures, as well as measures of motion perception (e.g., references

19–23). An association between eye-tracking abnormalities and NMDA receptor antagonism is important because it suggests what neurophysiological mechanisms are related to eye-tracking abnormalities. Despite numerous studies of eye tracking in patients with schizophrenia, it remains unclear what brain regions and receptor systems are involved. There is strong evidence that eye-tracking abnormalities are related to genetic risk for schizophrenia

(24,

25); thus, a relationship between eye tracking and NMDA antagonism may also help us understand the biological underpinnings of disease vulnerability.

Many of the eye-tracking studies of schizophrenia patients have used global performance measures, such as root mean square error or pursuit gain. Although important in establishing the presence of disease-related abnormalities, these measures have been less informative with regard to the specific nature and neuronal localization of the deficit(s)

(26). Several investigators have attempted to measure specific components of the smooth-pursuit response with encouraging results. Thaker et al.

(22,

27) used target masking, a procedure in which gain is measured during brief periods of target extinction, to assess the extraretinal component of the smooth-pursuit response. On the basis of these experiments, they argued that poor eye tracking may be explained in part by an inability to use previous target motion information to produce predictive eye movements during pursuit. A predictive pursuit deficit would implicate several brain regions, including the medial-superior-temporal and posterior-parietal cortex and frontal eye fields

(28–

30).

Another specific aspect of the smooth-pursuit response that has received recent attention involves the appearance of disruptive rapid eye movements ahead of the target. Large-amplitude (>4°) eye movements of this type are called “anticipatory saccades.” Several investigators have found that patients produce more anticipatory saccades during pursuit than healthy comparison subjects

(31–

33). Studies by Ross et al.

(21,

34–36) and others

(37) have suggested that the presence of anticipatory saccadic eye movements is related to schizophrenia vulnerability. Patient and family differences appear particularly robust when small-amplitude (<4°) anticipatory saccades (also called leading saccades) are included

(38). For example, Ross et al.

(21) reported that the combined presence of anticipatory and leading saccades was the only eye-tracking measure to discriminate likely genetic carriers from familial and nonfamilial healthy comparison subjects. Abnormalities in leading-saccadic eye movements implicate a neuronal pathway from frontal eye fields to the cerebellum

(21,

39–41). Of interest, both predictive pursuit and leading-saccade measures appear to improve the identification of likely genetic carriers compared with global measures

(37).

The role of NMDA receptors in producing eye-tracking abnormalities is not well understood. However, many of the brain regions implicated in these abnormalities show changes in regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) during ketamine administration. Radant et al.

(16) found that ketamine decreased closed-loop pursuit gain and increased the number of catch-up saccades in normal healthy volunteers. Weiler et al.

(17) found that ketamine decreased eye-movement acceleration during the initiation of smooth pursuit and decreased closed-loop pursuit gain. Of interest, ketamine did not affect predictive pursuit gain during target masking.

The effects of ketamine on anticipatory/leading saccades have not been examined. In light of recent reports suggesting that leading-saccade measures mark disease risk, we reanalyzed the data from Weiler et al.

(17) to obtain leading-saccade data. On the basis of overlapping patterns of neuronal activation (e.g., in the cerebellum and prefrontal areas) observed during ketamine infusion

(5–

7) and during eye-tracking imaging

(39), we hypothesized that ketamine would increase the frequency of leading saccades. Ketamine-induced changes would suggest a possible link between NMDA receptor functioning, neurophysiological deficit, and disease vulnerability.

Method

Clinical Assessments

Participants were recruited from the community through newspaper advertisements. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with guidelines from the institutional review board of the University of Maryland. Participants were screened for axis I and axis II disorders by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders

(42), and the Chapman Scales for Perceptual Aberration

(43) with previously published methods

(17,

22). Subjects underwent a medical history, a physical examination, and laboratory tests, including a drug screen. Participants with current or lifetime axis I or II disorders (including substance abuse), neurological disorders, a positive drug screen, or medical conditions that would render ketamine infusion unsafe were excluded from the study. Subjects were taking no medications at the time of testing.

The study participants were 10 men and two women. Their mean age was 34 years (SD=7). The relationship between age and eye-tracking performance is nonlinear, with significant deterioration appearing only after the age of about 50

(44). Mean socioeconomic status, measured with the Hollingshead-Redlich Scale

(45), was 2.7 (range=1–5; higher values indicate lower socioeconomic status). All participants had previous exposure to ketamine in a laboratory setting. The average number of days between ketamine infusions was 159 (range=42–410). No adverse reactions to ketamine were observed, and all participants were able to complete the study protocol.

Laboratory Procedures

The ramp-mask-ramp task used in the present experiment has been described previously

(17,

22). A foveal-petal step ramp was presented, followed by target motion in a horizontal plane, back and forth, at a constant velocity. After approximately two to three sweeps across the monitor, the target was unpredictably masked for 500 msec. Analysis of eye movements during the mask had been reported previously

(17). Here, we focused on the anticipatory/leading-saccadic eye movements occurring during visible target motion. Target presentations were performed in blocks of 12 trials (six at 9.4°/second and six at 18.7°/second). Each trial consisted of four to five sweeps and one mask. The order of the trials within each block was randomly chosen. Each block of trials lasted approximately 3.5 minutes.

On each of 2 study days, the subjects had an intravenous catheter placed with a saline drip. Pulse rate and oxygen saturation were continuously monitored. After several baseline eye-tracking blocks, participants were given a ketamine (0.1 mg/kg) or placebo bolus injection over 1 minute in a double-blind fashion. Subjects were then tested on the remaining blocks. After the task, symptoms were assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Participants were randomly chosen such that six received ketamine and six received placebo on the first study day.

The dose of 0.1 mg/kg was chosen on the basis of previous dose-ranging studies. At this dose, ketamine induces mild psychotic symptoms (e.g., visual and bodily distortions), a mild blunting of affect, and greater emotional withdrawal

(14). No significant blood pressure or pulse changes are noted, and no optical nystagmus is observed. Peak behavioral effects at this dose occur approximately 3 minutes after injection and last approximately 10–20 minutes. Although blood plasma levels were not obtained, previous analyses have shown that levels remain high up to 10 minutes postinfusion. Lahti et al.

(14) reported mean ketamine serum levels of 110.1 ng/ml (SD=21.4) after 10 minutes and 72.5 ng/ml (SD=21.4) after 20 minutes at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg. In order to ensure that eye-tracking performance was assessed during the period of peak behavioral effects, the eye-tracking block performed immediately after the bolus injection was analyzed.

Oculomotor Data Acquisition

Eye-movement data were obtained by using infrared oculography (with a 333-Hz sampling rate and a 4-msec time constant). Data were digitized with a 16-bit analogue-to-digital converter. Digital data were filtered offline with a low-pass filter (cutoff level=75 Hz). Eye movements were analyzed with investigators blind to drug condition with interactive software. Saccades were identified by computer algorithm on the basis of velocity (>35°/second) and acceleration (>600°/second2) criteria and verified by visual inspection. Eye blinks were identified on the basis of characteristic morphology and removed (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] reliabilities were above 0.95).

Saccades were identified with computer algorithm and verified by visual inspection (ICC=0.95). Calkins et al.

(46) have shown that eye blinks can be misidentified as anticipatory saccades when infrared oculography is used. However, they suggested that the identification of anticipatory saccades of 1°–4° in amplitude is less vulnerable to misclassification. In the present study, no amplitude criteria were employed in classifying anticipatory/leading saccades. Hereafter, we refer to both types of saccades as “leading.” Saccades were classified as “leading” if they 1) occurred in the direction of target motion, 2) either began and ended ahead of the target or if they began behind the target and jumped to a position ahead of the target, resulting in a position error equal to or greater than the original position error, or 3) were followed by at least a 50-msec period of eye velocity at 50% of target velocity for the 18.7°/second targets and 75% of target velocity for the 9.4°/second targets. Study criteria, based on amplitude, position error, and postsaccadic slowing, came from Ross et al.

(44) and others

(32,

39,

47). Across all conditions, a total of 730 leading saccades were identified, with a mean amplitude of 2.01° (SD=1.4). This falls within the amplitude range shown by Ross et al.

(44) to maximally discriminate patients from healthy comparison subjects and the range suggested by Calkins et al.

(46) to be less vulnerable to misclassification.

Three saccadic measures were assessed as follows: 1) The number of leading saccades occurring during 9.4°/second and 18.7°/second target trials were totaled for each block. 2) The ratio of time spent in leading saccades to the time spent in pursuit of the target was calculated. This is similar to the percentage of total distance owing to leading saccades, used by Ross et al.

(38), and is designed to assess what percentage of visual tracking is accomplished through leading-saccadic eye movements. 3) The ratio of time spent in leading saccades to the time spent in all saccades was calculated. The ratio of time in leading to total saccades was used to evaluate the change in leading saccades relative to changes in saccadic eye movements in general. This measure is particularly important for providing evidence that leading-saccadic eye movements represent a biologically distinct schizophrenia marker.

Statistical Analyses

Preliminary analyses showed no effects of treatment order or gender. Therefore, the data were collapsed across these factors. For each participant, data were collapsed across trials to obtain mean values. The age of the subjects was not correlated with leading-saccade values or changes in leading-saccade values across treatment, phase, or target velocity conditions. The distributions for each leading-saccade measure across treatment and target velocity conditions were examined. The data approximated a normal distribution (skewness/standard error ≥2.00). Separate repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed for 9.4°/second-target and 18.7°/second-target velocities. Phase (baseline or peak [i.e., the block immediately following the infusion]) and treatment (placebo or ketamine) were entered as within-subjects factors. Analyses of simple effects were used to probe significant interactions

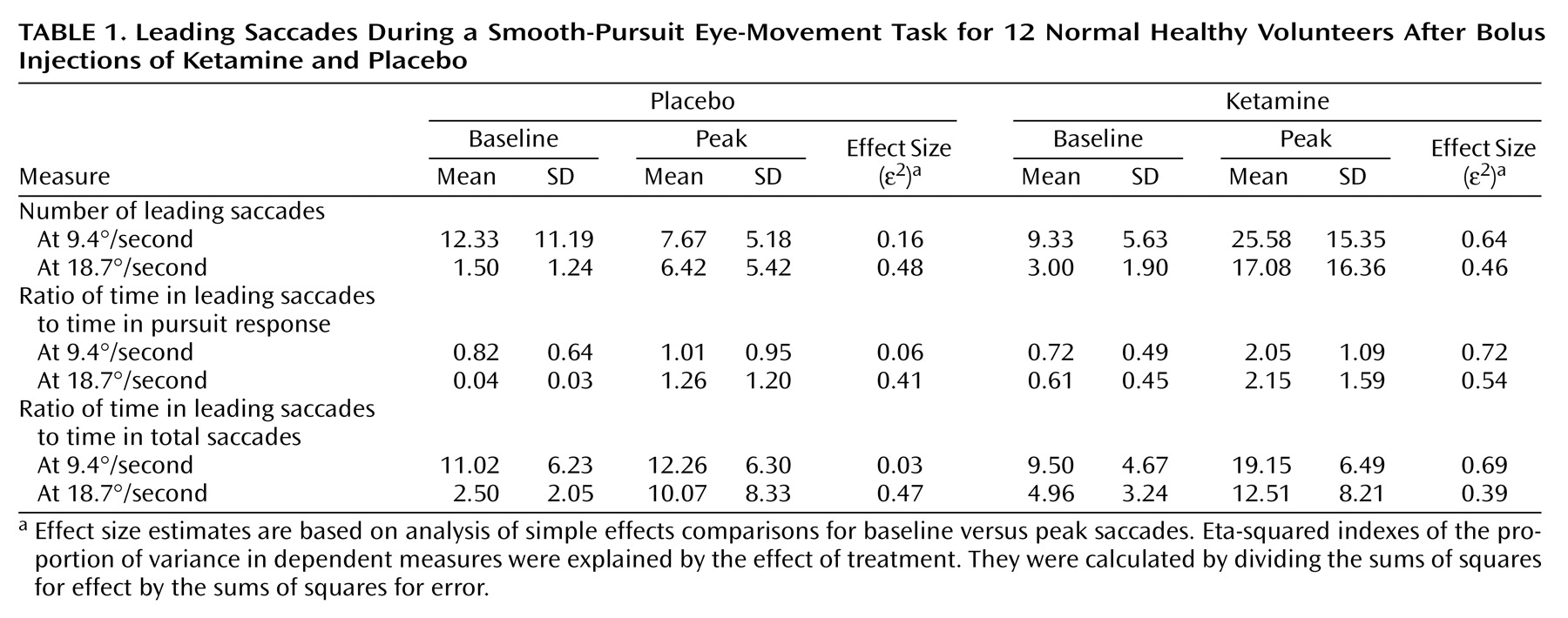

(48). Means, standard deviations, and effect sizes are presented in

Table 1.

Results

ANOVAs yielded statistically significant phase-by-treatment interactions for the number of leading saccades (F=16.54, df=1, 11, p=0.002), the ratio of time in leading saccades to time in pursuit (F=10.70, df=1, 11, p=0.007), and the ratio of time in leading saccades to time in total saccades (F=7.27, df=1, 11, p=0.02) for 9.4°/second target presentations. Simple-effects analyses showed significant increases in these measures from baseline to peak in the ketamine condition (p<0.001)—indicating an increase in the time spent off target. No significant changes occurred during the placebo condition on any measure.

The phase-by-treatment interaction for the number of leading saccades in the 18.7°/second condition was nearly significant (F=4.13, df=1, 11, p<0.07). The pattern of differences was similar, although less dramatic, in comparison to that reported for the slower target velocity. Analysis of simple effects showed that there was a significant increase from baseline to peak values for patients receiving ketamine (p=0.01); however, baseline to peak changes in patients receiving placebo were also significant (p<0.01). Phase-by-treatment interactions for the ratio of time in leading saccades to time in pursuit and the ratio of time in leading saccades to time in total saccades were not statistically significant at the 18.7°/second velocity (F=1.74, df=1, 11, p=0.21; F<1.00, df=1, 11, p=0.99, respectively). Both measures were significantly higher at peak compared to their values at baseline (i.e., main effects of phase collapsed across treatment conditions: F=17.04, df=1, 11, p=0.002; F=12.07, df=1, 11, p=0.005, respectively). The ratio of time in leading saccades to time in pursuit was nearly significant in patients receiving ketamine than in patients receiving placebo (i.e., main effect of treatment condition collapsed across phase: F=3.88, df=1, 11, p<0.08).

As reported previously

(17), total BPRS scores showed a modest increase from baseline (mean=18.36, SD=0.50) to ketamine infusion (mean=20.00, SD=2.46), reflecting mild increases in score on the withdrawal and thought disorder subscales. No significant correlations were found between ketamine-induced changes in BPRS score and leading-saccade measures (correlations ranged from –0.01 to 0.46; most were <0.25). This is consistent with what we observed for patient BPRS scores and leading-saccade measures (unpublished data).

Discussion

Our results support the hypothesis that ketamine increases leading-saccadic eye movements during smooth pursuit. Because leading saccades move the eyes away from the target at a point in which initial position error is small, their presence is considered disruptive and indicative of poor performance. All three measures used in this study were significantly greater with use of ketamine in the 9.4°/second target condition. Only the number of leading saccades showed a similar but nonsignificant interaction in the 18.7°/second target condition. The ratio of time in leading saccades to time in pursuit and the ratio of time in leading saccades to total time in saccades showed a main effect of phase; the ratio of time in leading saccades to time in pursuit showed a nearly significant effect of ketamine. The effect of phase, in the absence of significant phase-by-treatment interactions, suggests that at higher target speeds, the difficulty of the task (a function of the target speed) may interact with fatigue (a function of repeated target presentations) to mask specific ketamine effects.

A robust effect of ketamine was observed in the slower target condition. This effect was not caused by an overall increase in saccadic frequency, since changes in the ratio of time in leading saccades to total time in saccades reflect a change in leading saccades above and beyond changes in overall saccadic output. The specificity of this pharmacological effect suggests that leading-saccadic eye movements are a specific marker of schizophrenia risk and supports the conclusions of Ross et al.

(21,

34,

35). These results contrast with those of Radant et al.

(16), who found no effect of ketamine on anticipatory saccades. Several factors may account for this discrepancy. 1) Radant et al. administered a dose sufficient to cause nystagmus, which makes the identification of leading saccades more difficult. 2) Consistent with the definitional criteria of leading saccades used by Ross et al., we included small (<4°) leading saccades. Traditionally, only saccades larger than 5° have been considered relevant. 3) Radant et al. included 20°/second targets. On the basis of our data, the inclusion of the higher target velocity may have masked the effects of ketamine.

Evidence from neuroimaging

(39) and microstimulation studies

(41,

49) suggests that cerebellar circuitry is involved in integrating and coordinating smooth-pursuit and saccadic eye-movement information from the frontal cortex

(40,

50) via a frontal-thalamic-cerebellar circuit. Ross et al.

(21) argued that abnormalities in this circuit may underlie schizophrenia-related eye-tracking abnormalities. NMDA receptors are present on cells throughout the cortex, including the frontal/prefrontal cortex and the cerebellum

(18,

51,

52), where they could play a functional role in eye-tracking abnormalities. Ketamine is a noncompetitive antagonist of the NMDA receptor in these regions; thus, data from the present study are consistent with a model of eye-tracking abnormality mediated, in part, by NMDA receptor functioning within the frontal-thalamic-cerebellar circuit.

Where in this putative circuit an NMDA-induced abnormality might exist is difficult to infer. However, the absence of ketamine effects on predictive pursuit

(17) suggests that the processing of extraretinal motion signals by superior mediotemporal and posterior-parietal cortical regions is spared. Similarly, frontal eye fields are likely unaffected because they mediate integration of extraretinal motion information into an ocular motor command. Also, greater rCBF in frontal areas observed during ketamine positron emission tomography imaging is more prominent in medial-frontal anterior cingulate areas than in the lateral frontal areas that include the frontal eye fields

(8). In contrast, NMDA antagonism by ketamine is known to potently decrease neuronal activity in the cerebellum

(8,

53), an action that can explain the observed deficits in pursuit initiation

(17) and pursuit maintenance

(16,

17), as well as increases in disruptive leading saccades during smooth pursuit

(54–

56). Several investigators have noted functional cerebellar abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia

(57–

59). Thus, it is possible that some of the eye-tracking deficits associated with schizophrenia risk and seen during ketamine challenge are mediated by shared cerebellar pathophysiology. This conclusion must be tempered by the possibility that changes in eye-tracking performance may be mediated through other receptor and neurotransmitter systems known to be effected by ketamine

(1,

60,

61).

Given the ability of leading-saccade measures to identify schizophrenic patients and their relatives

(21,

35,

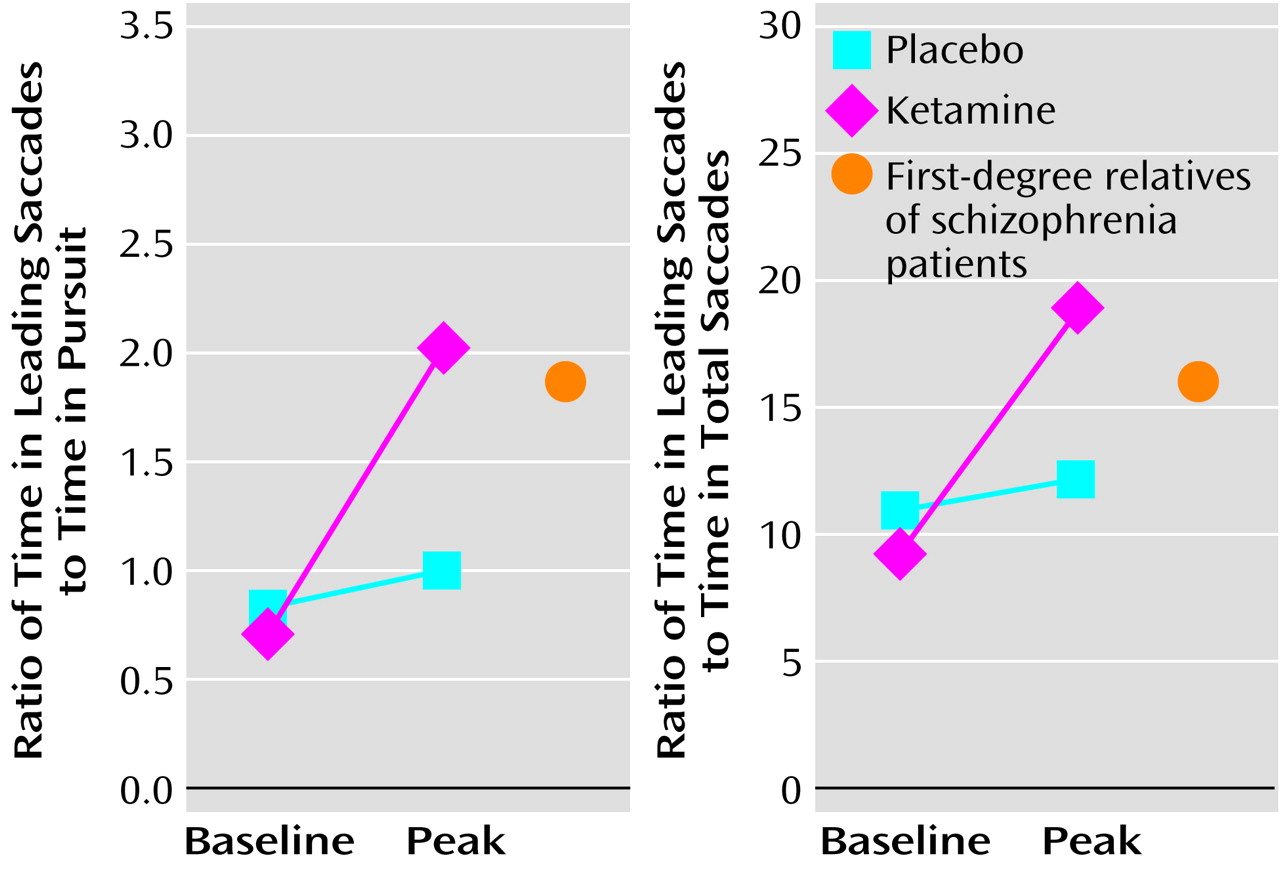

37), ketamine-induced changes in leading saccades may lend insight into the possible neurophysiological underpinnings of disease risk. In this context, it would be informative to compare the eye-tracking performance of normal healthy volunteers during ketamine infusion to that of at-risk relatives of schizophrenia patients in the absence of ketamine. Similar values would suggest that the mechanisms leading to saccadic disturbance in the relatives of schizophrenia patients are similar to those operating in normal comparison subjects under conditions of NMDA antagonism. Some preliminary data are available from our laboratory to explore this question and are presented in

Figure 1. Of interest, the values for the normal healthy volunteers receiving ketamine are similar to those of a group of first-degree relatives with schizophrenia spectrum symptoms, taken from Avila et al.

(37). Interpretation of these data must be tempered by the possibility that normal values would change with different doses of ketamine. Nonetheless, this pattern of results, in conjunction with the neuroanatomical and neurofunctional evidence reviewed previously, raises the possibility that one of the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying genetic risk and marked by saccadic abnormalities involves NMDA-mediated neurotransmission in the cerebellum.