Studies have shown that there is substantial comorbidity between mental illness and diabetes

(3,

4), and a growing body of literature is focused on the link between the two. The use of antipsychotics

(5,

6) and antidepressants

(7) as well as higher rates of obesity, poor diet, physical inactivity, and smoking

(8,

9) all serve to increase the risk of diabetes among the mentally ill. In addition, higher mortality due to diabetes has been observed among mentally ill individuals than in the general population

(10,

11).

Many of the complications of diabetes—such as foot ulcers, amputations, neuropathy, and blindness—are largely preventable, and groups such as the American Diabetes Association have issued clinical guidelines and standards for the management of patients with diabetes

(17). Given that persons with mental disorders are at a greater risk for diabetes-related morbidity and mortality and that they represent a population that is potentially vulnerable to poorer quality of medical care

(18–

21), it is important to focus attention on the quality of diabetes care received by such patients.

To date, we are aware of no empirical studies that have examined the association between mental illness and quality of diabetes care. In the present study, we examined this relationship in a national sample of veterans with diabetes. We hypothesized that patients with mental disorders receive poorer quality of care than do those with no mental disorder, as determined by five chart-based quality indicators (chart documentation of foot inspection, pedal pulses examination, foot sensory examination, retina examination, and glycated hemoglobin determination in the past year), with control for demographic characteristics, health status, use of medical services, and hospital-level characteristics.

Results

The study sample included 38,020 patients with diabetes from 146 VA medical centers. Overall, more than a quarter of the sample had a diagnosed mental disorder (23.7% [N=9,025] with psychiatric disorder only, 1.3% [N=505] with substance use disorder only, and 2.6% [N=987] with a dual diagnosis). The prevalence of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder was 4.3% (N=1,616); major affective disorder, 7.7% (N=2,931); and PTSD, 5.3% (N=2,023).

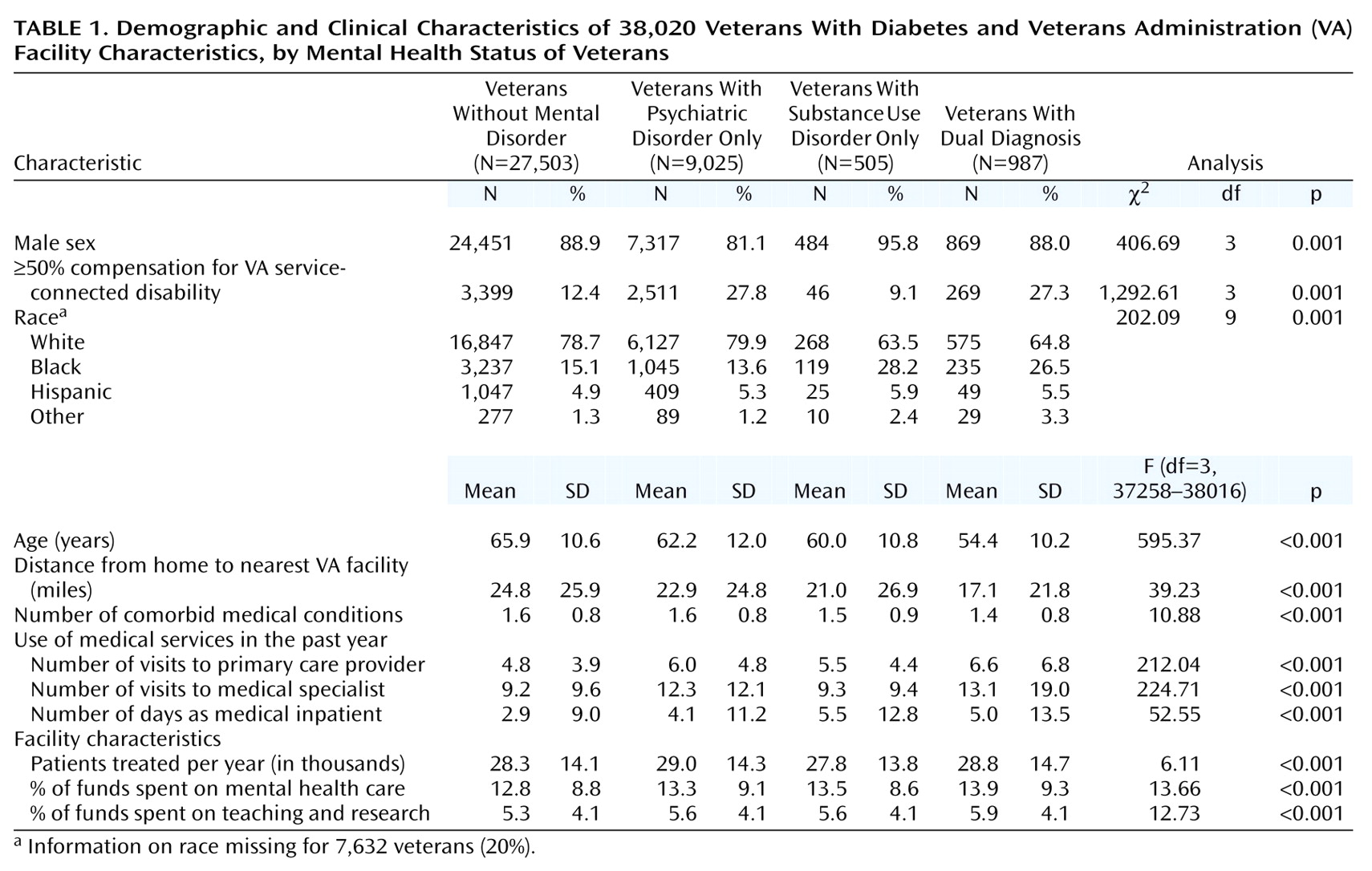

Table 1 presents a description of the sample. In general, compared with patients without mental disorders, mentally ill patients were more likely to be younger, female (except those with a substance use disorder only), and nonwhite. Persons with a psychiatric disorder or dual diagnosis were more than twice as likely as those without mental disorders to receive VA compensation for a ≥50% service-connected disability; patients with a substance use disorder only were the least likely to have a service-connected disability. On average, patients with a mental disorder lived closer to a VA medical center, had fewer comorbid medical conditions, and used more outpatient and inpatient medical services in the previous year than patients without a mental disorder. In addition, those with a mental disorder were more likely to be treated at VA facilities that spend a greater proportion of funds on teaching and research, are larger in terms of annual patient volume, and spend a greater proportion on mental health versus general health care.

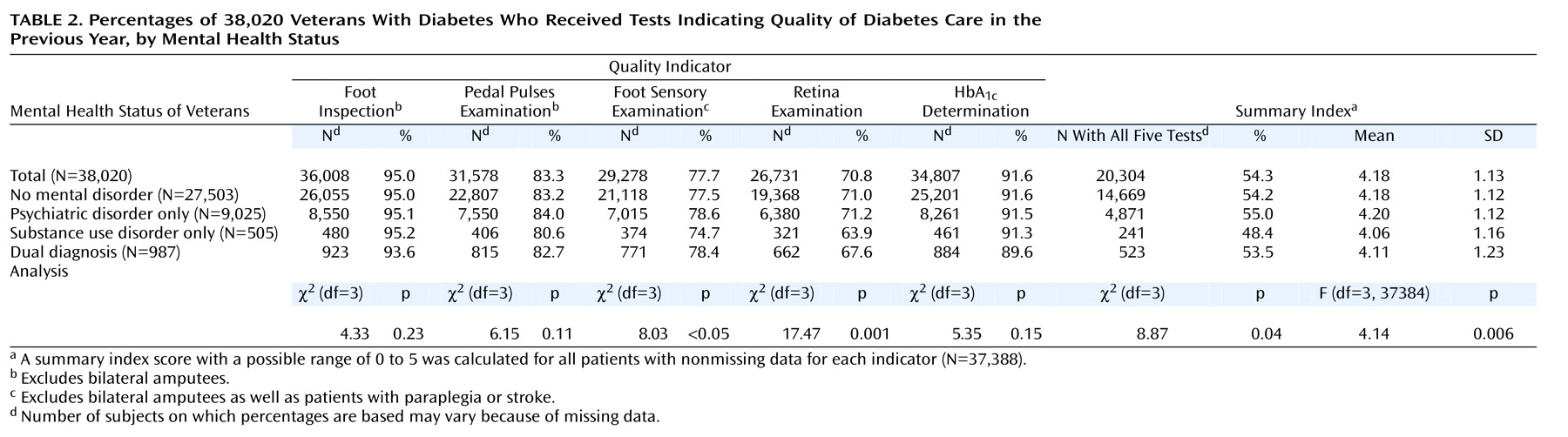

Table 2 presents the percentage of patients with chart-documented receipt of the diabetes quality indicators. Overall rates for the individual indicators were high, ranging from 70.8% for retina examination to 95.0% for foot inspection; however, only 54.3% of the sample received all five medical interventions in the past year. On average, patients received 4.18 interventions.

In unadjusted analyses, rates for two of the five quality indicators—retina examination and foot sensory examination—differed significantly by mental health status, primarily because of lower rates among those with a substance use disorder only (

Table 2). In these data, we did not find consistent evidence that patients with a serious psychiatric illness (namely, major affective disorder, psychotic disorders, or PTSD) or patients who had had a mental health inpatient stay were at any greater risk for poorer quality of diabetes care (data not shown). The observed associations between substance use disorder and quality of care remained significant after control for potential confounders and did not significantly change over the study period as overall quality improved (data not shown).

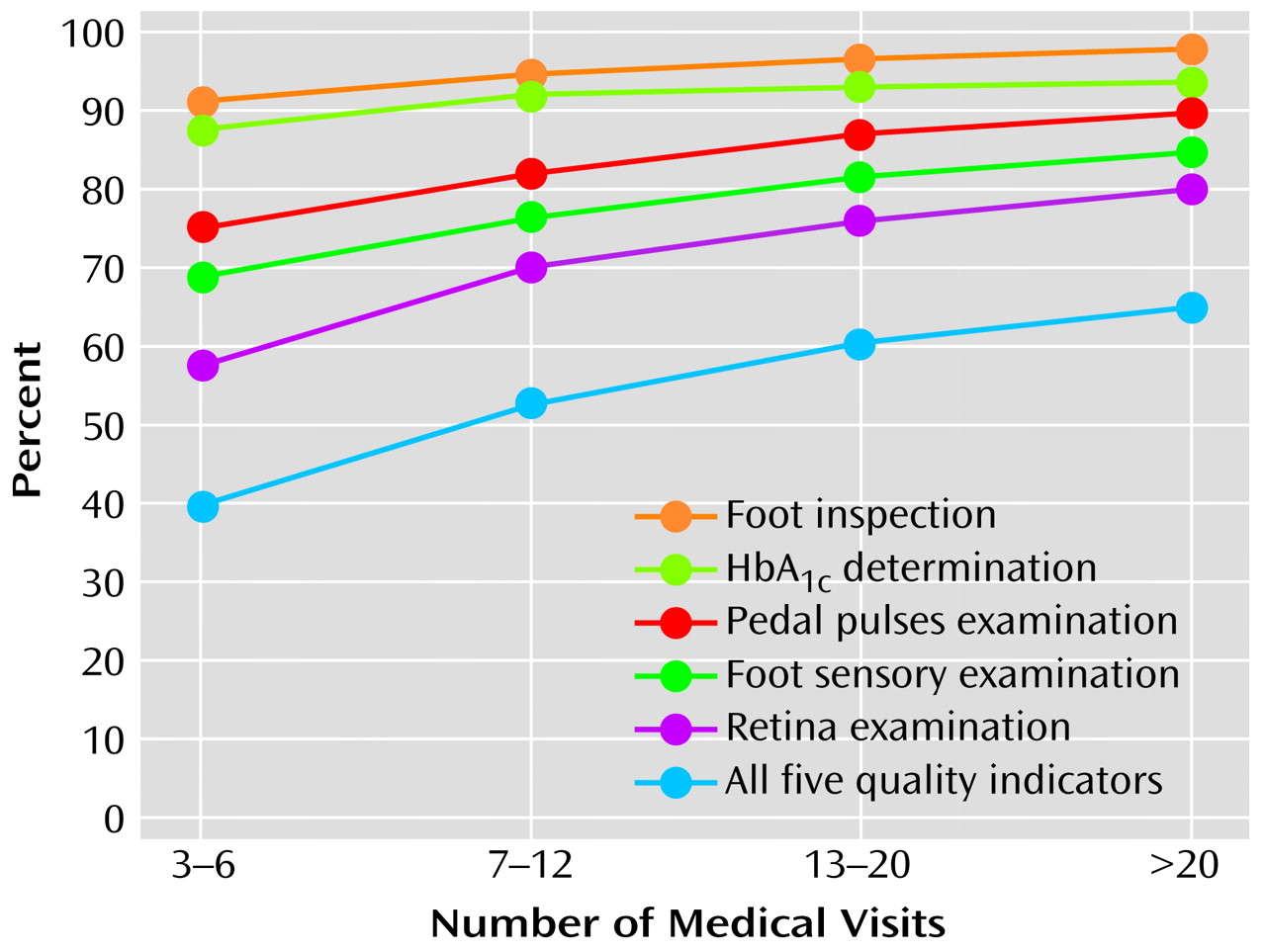

Overall, contrary to our hypothesis, persons with psychiatric disorders did not receive poorer quality of care than those without such disorders (

Table 2). The fact that patients with psychiatric disorders had significantly more medical outpatient visits in the previous year than other patients (

Table 1) and that the number of visits was positively associated with the likelihood of receiving the quality indicators (

Figure 1) suggests that the high quality of care received by persons with a psychiatric disorder might have been, at least in part, attributed to their greater use of medical services and, therefore, more opportunities for receiving the interventions. Indeed, whereas rates for retina examination, for example, were nearly identical among patients with a psychiatric disorder only (71.2%) compared with those without a mental disorder (71.0%) in unadjusted analyses (

Table 2), a significant negative association was found in multivariate analyses with control for medical visits (odds ratio=0.86, p<0.001). A similar relationship was found with respect to HbA

1c determination but not the other quality indicators (data not shown).

In addition to mental health status and the number of medical visits, several other study variables were significantly associated with receipt of the quality indicators (data not shown). Higher quality index scores were found among male, black, and Hispanic patients as well as patients who were at least 50% VA service connected and who had fewer comorbid medical conditions. The number of medical inpatient days was positively associated with foot inspection and pedal pulses examination but negatively associated with retina examination and HbA1c determination. Quality of diabetes care differed little by facility-level characteristics, with the following exceptions: patients who sought care either at larger hospitals or at hospitals that spend a greater proportion of funds on mental health were less likely to have their feet inspected, while patients treated at VA medical centers with a greater academic emphasis were more likely to have their glycated hemoglobin levels checked.

Discussion

In this large national sample of veterans with diabetes, we found remarkably high rates of receipt for five quality-of-care indicators, ranging from 70.8% for retina examination to 95.0% for foot inspection; on average, patients received 4.18 interventions in the previous year. These observed rates for diabetes-related secondary prevention measures exceed national performance standards for managed-care organizations

(30) as well as rates reported in population-based samples

(31–

34). For example, according to data from the 2000 Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set

(30), mean rates for HbA

1c testing and eye examinations were 75.1% and 45.3%, respectively, across health plans. Of note, even the rates we observed among patients with mental disorders exceed these national benchmarks. Caution is warranted, however, when making comparisons across health care systems because of differences in the methods for obtaining these measures

(35). The high rates of compliance with the quality indicators and the modest differences by mental health status may, in part, be attributed to the regular feedback provided by the External Peer Review Program to VA medical center clinical leaders and administrators. In addition, the VA’s use of electronic medical records is likely to promote greater coordination of patient care.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found little difference in quality of diabetes care between patients with and without mental disorders. Rates for two of the five indicators—retina examination and foot sensory examination—differed significantly by mental health status in unadjusted analyses, primarily because of lower rates among the relatively small group of patients with substance use disorders. The associations remained significant even after control for a variety of demographic characteristics, health status, use of medical services, and facility characteristics.

Both patient and provider factors may have contributed to the observed differences in quality of care. With respect to receiving an annual retina examination, for example, patients with substance use disorders may have been less likely, for a variety of reasons, to receive and/or follow-up on ophthalmological referrals. Studies have found that generalists often have difficulty serving the medical needs of patients with substance use disorders

(36). In addition, such patients are often stigmatized by health care providers

(37), which may further serve to interfere with the delivery of appropriate care. Moreover, the cognitive, affective, and behavioral symptoms associated with mental disorders may hinder effective, collaborative patient-physician communication, which has been shown to be important in improving adherence and outcomes for chronic medical conditions

(38–

40).

It is not clear why a more consistent pattern of associations was not found across all of the quality indicators. Although we cannot exclude the role of chance or potential errors in abstracting or coding the data, it is interesting to note that interventions such as the foot inspection and pedal pulses examination, for which no significant difference in quality was observed, are simple procedures performed by a single provider. In contrast, receipt of a retina examination—the intervention for which the greatest disparity was observed—requires a coordinated effort from referral to scheduling an appointment to follow through by the patient. Although it was based on a relatively small number of patients, the finding that persons with substance use disorders were less likely to have had a retina examination in the previous year is important given that diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness among adults in the United States

(41) and can be prevented if detected early.

The findings of this study may not apply to non-VA settings. Indeed, unique aspects of the study population and the Veterans Health Administration system suggest that these findings likely underestimate the difference in diabetes care received by persons with and without mental disorders in other health care settings. First, this was a select sample in that all of the patients had at least three outpatient visits in the past year, suggesting that they were well engaged with the medical system. Second, the Veterans Health Administration is a fully integrated health care system geared toward caring for the mentally ill, with approximately 20% of the general patient population having a mental disorder

(26). Third, unlike those in other settings, patients in the Veterans Health Administration system do not face constraints on health care services use. In other settings, which are more fragmented or which attempt to contain costs by limiting outpatient services, mentally ill patients may be at greater risk for poorer quality of care.

This is underscored by our finding that number of medical visits appeared to be a mediator in this study, such that patients with a psychiatric disorder seemed to receive similar quality of care as those without a mental disorder, in part, as a result of more visits. In other words, we found that vulnerability conferred by mental illness was, to some extent, compensated for by more use of medical services. In national surveys, mentally ill persons have reported worse health insurance coverage

(42) and poorer access to care

(42,

43) than those without a mental disorder; therefore, this compensatory effect of greater use may not operate in other health care settings. Future studies should examine the relationship between mental illness and quality of diabetes care in other patient populations and settings.

Although not a primary focus of this study, several other variables were significantly associated with quality of diabetes care and deserve brief comment. It is not clear why men received better diabetes care than women. While it has been observed that the Veterans Health Administration is a male-dominated system geared to treat a mostly male population and that female veterans underuse VA health services

(44,

45), the association persisted even after control for use of medical services. Moreover, this finding is consistent with a population-based study of persons with diabetes

(31), suggesting that the gender difference in quality is not unique to the VA setting.

It is also not clear why black and Hispanic patients tended to receive better care than others. It may be that they had more severe diabetes or had been living with their disease longer, resulting in greater awareness and recognition of the need for preventive care. Unfortunately, data were not available on factors such as specific disease severity or age at diagnosis. We found that the number of comorbid medical conditions was inversely associated with two of the indicators as well as the summary index. The presence of comorbidities may decrease the time and attention that can be devoted to any given condition

(20).

This study had the following limitations. First, our ability to control for potential confounders, such as race and medical comorbidity, was limited by the quality of the available administrative and chart-review data. Second, we did not have data on health care received outside of the VA system. Given that some veterans likely received additional medical services in non-VA settings, we may have underestimated the percentage of patients who received diabetes care in the past year. This underestimation, however, likely resulted in a bias toward the null, since patients without mental disorders may have been more likely to receive non-VA care, given, in part, their older age and greater Medicare eligibility.

In conclusion, rates for secondary prevention of diabetes were higher at VA medical centers than on national benchmarks; however, patients with substance use disorders were less likely than other patients to receive some of the recommended interventions, placing them at some greater risk for diabetes-related complications and disability as well as high health care costs. Strategies such as case management, extra time for office visits, and other interventions developed for the management of chronic illnesses

(46) may need to be adapted for use in patients with mental disorders. More work is needed to develop and test models for improving care in this vulnerable population.