Mood disorders, substance use disorders, and their comorbidity increase the risk for suicide attempts

(1–

3). Although not all attempters complete suicide, attempts increase the risk for completed suicide

(4). Understanding predictors of suicidal behavior, therefore, is important for clinical practice.

Many individuals with a substance use disorder also meet criteria for major depression

(5,

6). Research on comorbid substance dependence and major depression was facilitated with the DSM-IV definitions of primary or independent disorders and substance-induced disorders, distinctions based largely on timing. Substance-induced depression is defined as occurring during periods of substance use but exceeding the expected effects of intoxication or withdrawal from the substances used. Primary or independent major depression is defined as either predating substance use entirely or occurring during periods of sustained abstinence.

Defined this way, the timing of major depression among substance abusers and whether this affects the risk for suicidal behavior has not been extensively studied. In one study

(7), alcoholics with independent major depression were found to be more likely to attempt suicide than those with substance-induced depression. However, major depression that occurs before the onset of a substance-related disorder may relate differently to suicidal behavior than major depression that occurs during periods of sustained abstinence. The latter are more likely to occur while patients are in treatment. In this article, we investigate the effects on suicidal behavior of major depression and its timing relative to substance use in a diverse sample of patients who were dependent on drugs or alcohol. Specifically, we determined whether these patients had made any suicide attempts, the severity of intent at its worst, and the number of suicide attempts.

Method

As described elsewhere

(8), sequentially admitted patients 18 years old or older were recruited from dual-diagnosis inpatient, methadone maintenance, and outpatient drug counseling facilities. Inclusion criteria required alcohol, cocaine, or heroin use within 30 days of the interview (outpatients) or hospitalization (inpatients). Severely psychotic, medically ill, or homeless patients were excluded. Of eligible patients, 662 (92%) participated (information on the patients who refused to participate in the study is not available). After giving written informed consent and, if applicable, finishing withdrawal, patients were interviewed by experienced interviewers.

Lifetime major depression was assessed with the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders, a highly reliable interview for major depression among substance abusers

(9). Patients with primary or independent major depression were separated into two groups: those who experienced major depression before the onset of substance dependence (N=137) and those who experienced major depression during a period of abstinence (N=115). The third group of patients, those with major depression analogous to DSM-IV substance-induced depression (N=127), were diagnosed with more structure to improve reliability. Patients who met the definition of having major depression during substance use met full symptom and duration criteria for major depression as well as the requirement that the severity of any depressive symptoms accompanying depressed mood (e.g., insomnia) exceeded the severity of any depressive symptoms reported when using substances but not depressed. Major depression under these three circumstances defined mutually exclusive and hierarchical types: previous-onset depression took precedence over abstinence depression, which took precedence over substance-induced depression.

To measure suicide attempts, subjects were asked if they ever tried to kill themselves or started to do something like that even if they stopped (or were stopped). Attempters were asked the seriousness of their suicidal intent at its worst and the number of attempts. Seriousness was rated from 1 (no intent, manipulative gesture) to 6 (careful planning, death fully expected).

Logistic regression (controlling for demographic characteristics and type of substance dependence [alcohol, cocaine, or heroin]) was used to examine the relationship of type of major depression to dichotomous outcomes. The outcomes included any attempts versus none and no or mild suicidal intent versus moderate or extreme intent. Suicidal intent was dichotomized because severity was ranked rather than linearly increased, as assumed in linear regression. Adjusted odds ratios derived from these models are presented. Linear regression using the same controls was used to examine the relationship between depression type and number of attempts. Patients who planned suicide but never made attempts were excluded for later study (N=60). All tests were two-tailed.

Results

Of the 602 patients, 205 (34.1%) made a suicide attempt at least once. Among those who ever attempted suicide, 68 (33.2%) had previous-onset major depression, 51 (24.9%) had major depression during abstinence, and 52 (25.4%) had substance-induced major depression.

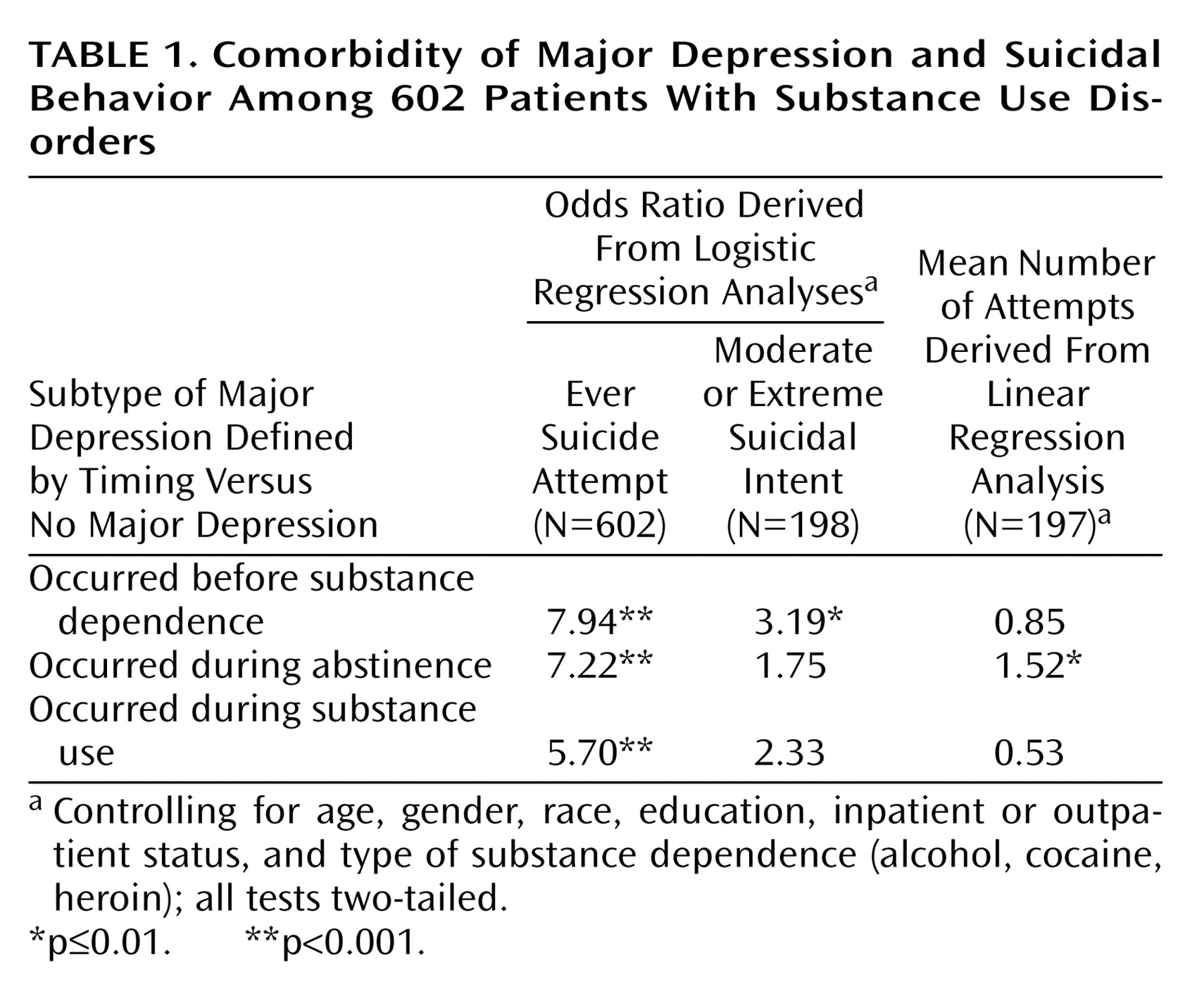

Table 1 shows the relationship between depression types and suicidal behaviors. All three types of major depression increased the odds of making an attempt. A post hoc test showed no difference in the effects of the three types (likelihood ratio test χ

2=1.35, df=2, p=0.49). Among subjects who had made any attempt, the mean rating of severity of intent was 3.7 (SD=1.4), reflecting at least moderate severity. Major depression that occurred before any substance dependence was significantly associated with at least moderately severe suicidal intent when nondepressed patients were used as the reference group. Among patients who had made any attempt, the mean number of attempts was 2.6 (SD=2.3, range=1–18), indicating that multiple attempts were a clinical issue in this group of patients. Major depression during abstinence significantly predicted a larger number of attempts.

Discussion

These results suggest the importance of assessing the timing of depression among substance-dependent patients along the lines suggested by DSM-IV. All three subtypes of major depression defined according to timing (previous to dependence, during abstinence, and during substance use) predicted occurrence of any suicide attempts, and this particularly supports the assertion of DSM-IV that substance-induced depression has clinical significance and should not be dismissed. That major depression with onset before substance dependence predicts severity of suicidal intent and major depression during abstinence predicts number of attempts supports the validity of DSM-IV primary depression as having serious prognostic implications. The findings also suggest the importance of distinguishing depression during abstinence as a risk period for suicide attempts. Clearly, remission of substance use is a welcome sign of clinical progress. However, special care may be needed to prevent suicide attempts in such patients, including careful review of the history of suicidal behavior and other risk factors for suicide as well as treatment of depression.

Limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of the data, the concentration of patients in only one metropolitan area, and reliance on patients’ self-reports. However, strengths include the large number of subjects and the use of clear interviewer guidelines for differentiating between types of depression. Furthermore, the study expands research on suicide attempts to patients abusing a wide range of substances, reflecting the heterogeneity clinicians commonly encounter in practice. Future research should focus on prospective evaluation of the effects of subtypes of DSM-IV depression and suicidal behavior among substance abusers.