The debate about optimal dosing of antipsychotic medication is still a lively one. Haase

(1) introduced the concept “neuroleptic threshold dose”: a dose at which patients develop minimal extrapyramidal side effects. Exceeding this dose resulted in more extrapyramidal side effects but not in a better response

(2). The concept of a “therapeutic window” emerged

(3). Since the 1980s, the occupancy of striatal dopamine D

2 receptors and, consequently, the “neuroleptic threshold dose” or “therapeutic window” has been assessed in vivo with scintigraphic techniques

(4–

6). It has been suggested that a D

2 receptor occupancy threshold in the range of 60%–70% is needed to obtain satisfactory antipsychotic response

(7–

9). A stepped increase in response was found beyond 65% D

2 receptor occupancy; prolactin elevation became prominent beyond 72%, while extrapyramidal side effects were evident beyond 78%

(10).

We hypothesized that there would also be a “window” for the influence of antipsychotic medication on the subjective experience of patients. In an earlier study, we found that levels of D

2 occupancy lower than those that cause extrapyramidal side effects may be related to negative subjective experience

(12). The “subjective side effect window” in dosing antipsychotic drugs may be small. We hypothesized that “optimal occupancy of D

2 receptors” would lie between 60% and 70%. We proposed that D

2 binding should not exceed 70% to avoid excessive inhibition of dopamine neurotransmission, resulting in a negative impact on subjective experience. On the other hand, D

2 occupancy below 60% leaves a patient in a psychotic state (too high a functional level of the dopamine system) accompanied by negative subjective well-being. This line of thought can be compared to the hypothesis about an optimal range in which D

2 receptor stimulation by drugs of abuse can be perceived as reinforcing: too little may not be sufficient, but too much may have an aversive effect

(16).

The development of a new generation of antipsychotic medications could be important in this respect. Olanzapine has been found to be associated with a better subjective experience than typical antipsychotic drugs

(21,

22). However, different levels of D

2 occupancy have confounded previous comparisons of antipsychotic drugs

(23). If the severity of negative subjective experience is related to D

2 receptor occupancy, then the new antipsychotic medications might not be more beneficial for subjective experience than typical antipsychotic drugs in doses with comparable D

2 receptor occupancy. Therefore, another strategy to improve the subjective experience might be treatment with low-dose typical antipsychotic drugs.

Limitations of earlier studies on subjective experience with typical and atypical antipsychotic medications were the noncomparative dosing and the lack of a randomized double-blind design. We therefore conducted a 6-week, randomized, double-blind study of fixed low-dose olanzapine or haloperidol in young patients with recent-onset schizophrenia. To study the relation between subjective experience and D2 receptor occupancy by these drugs, we assessed in vivo striatal dopamine D2 receptor occupancy with [123I]iodobenzamide ([123I]IBZM) single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

Results

Subjects

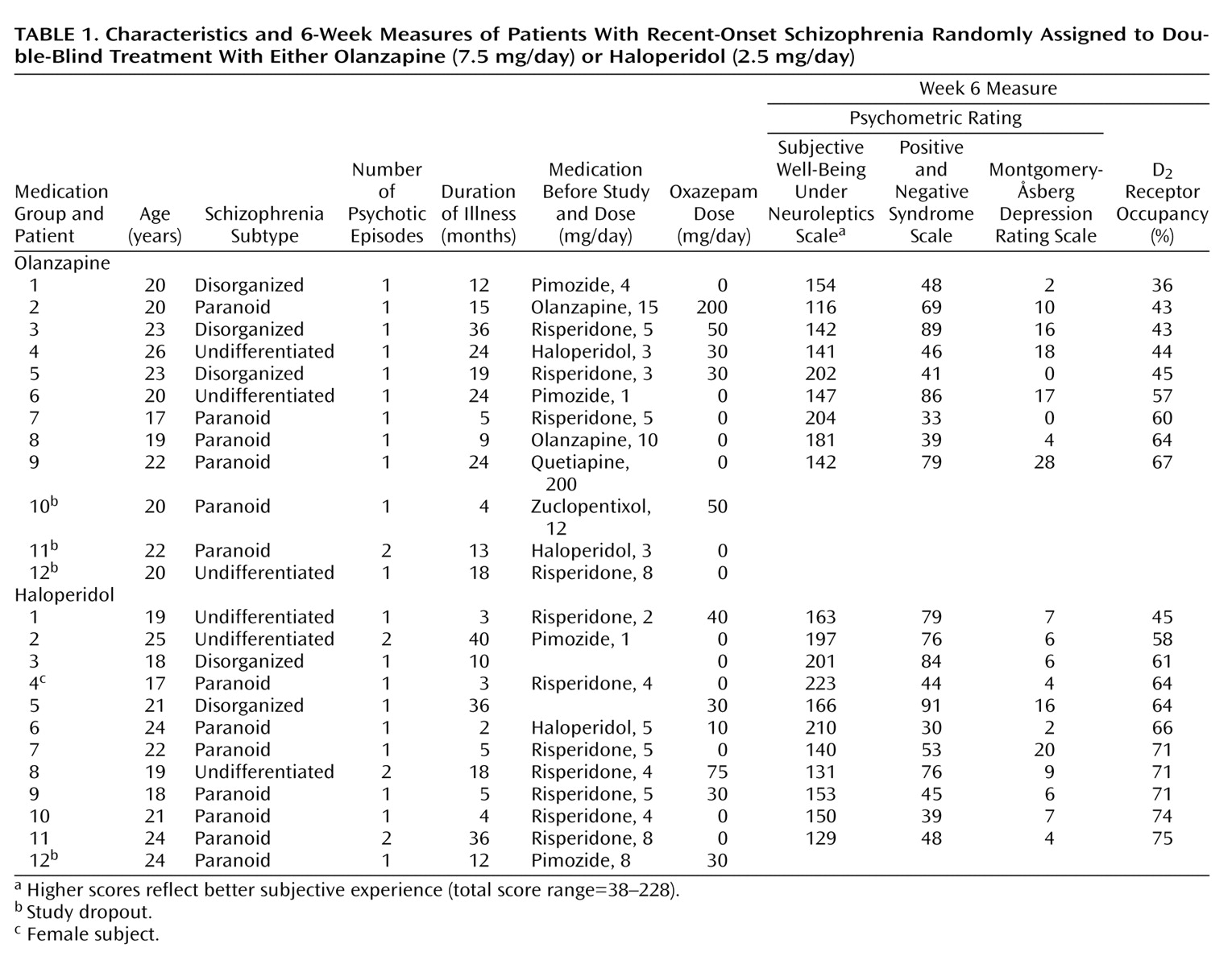

Twenty-four patients with schizophrenia according to DSM-IV criteria were included. Subjects’ characteristics, including characteristics of the illness and Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptics Scale total score, psychopathology ratings, and percentage of D

2 receptor occupancy at endpoint, are shown in

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants (sex, diagnosis, number of episodes, duration of psychosis, and prior treatment) treated with olanzapine did not significantly differ at baseline from the characteristics of participants treated with haloperidol.

Three patients treated with olanzapine and one patient treated with haloperidol dropped out. Reasons for dropping out were patient decision (N=2, both olanzapine) and increase of psychosis (N=2, one patient treated with haloperidol, one patient treated with olanzapine). There were no significant differences between patients who dropped out and study completers with respect to diagnosis, number of psychotic episodes, duration of psychotic symptoms, psychopathology, or subjective experience ratings.

Mean absolute difference between the positively and the comparative negatively formulated items of the Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptics Scale was 0.58 (SD=0.34). Only one patient (haloperidol group) had a mean absolute difference of 2 or higher (2.9). This assessment was considered to be not consistent and was excluded from analysis relating to subjective experience.

Subjective Experience and D2 Receptor Occupancy

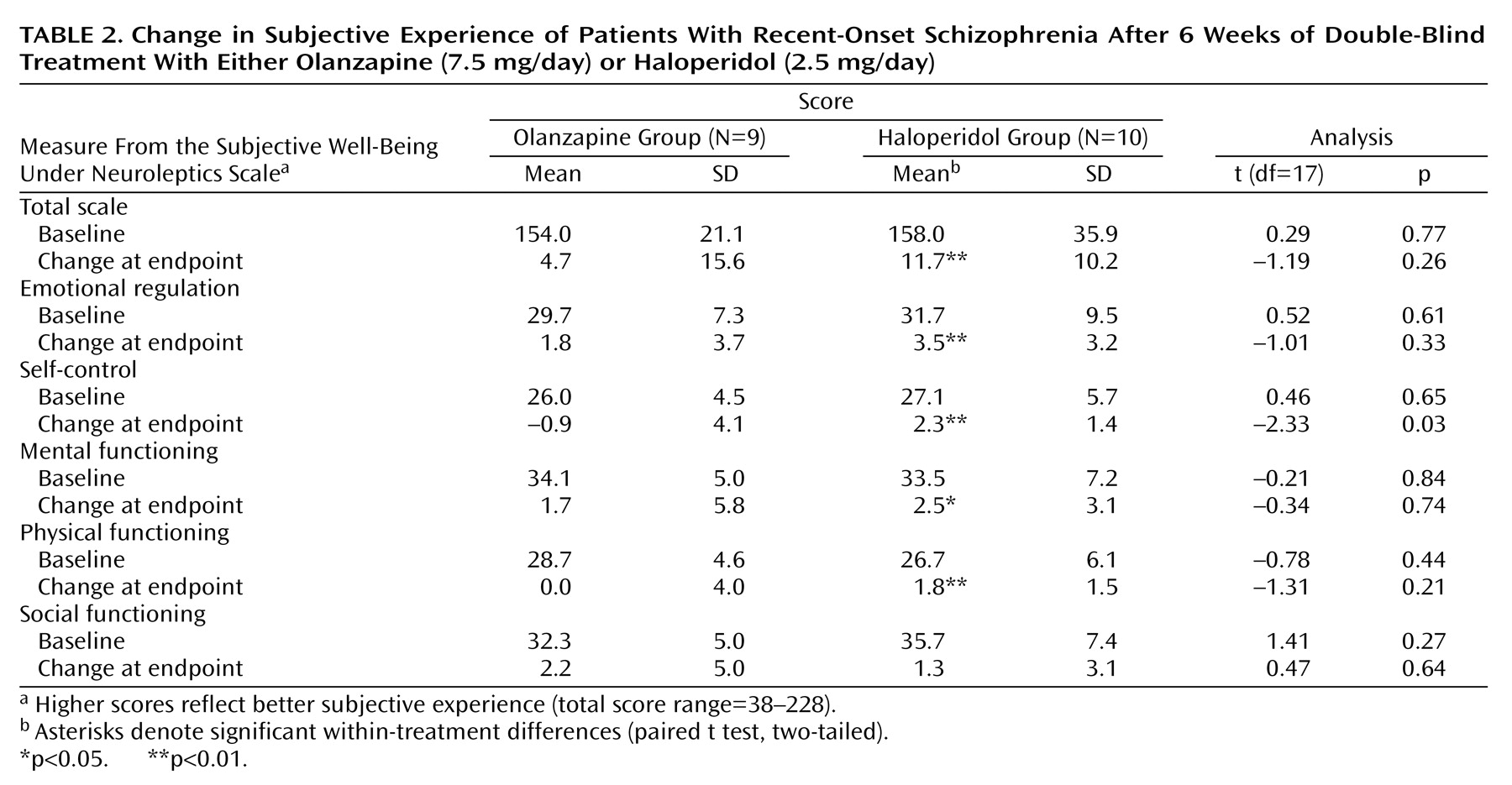

Mean baseline and change at endpoint scores for measures of the Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptics Scale did not differ significantly between participants treated with haloperidol or olanzapine except for a significant difference in the change at endpoint score for the self-control subscale in favor of haloperidol. Total score and four of the five subscale scores of the Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptics Scale improved significantly from baseline to endpoint in the patients treated with haloperidol (

Table 2).

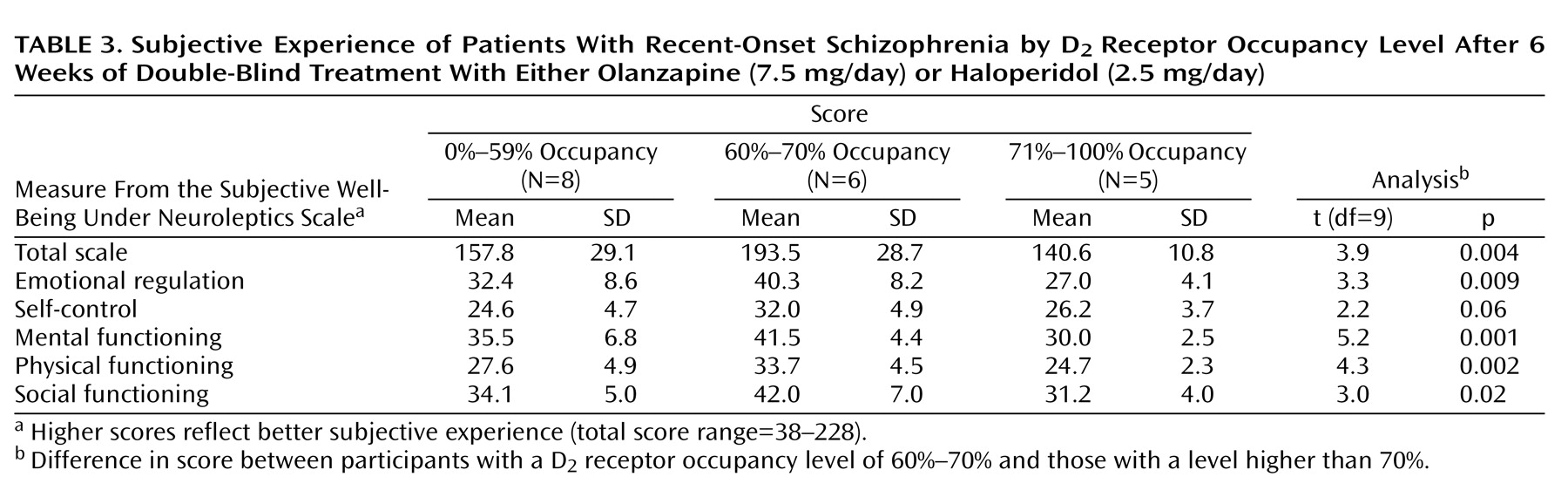

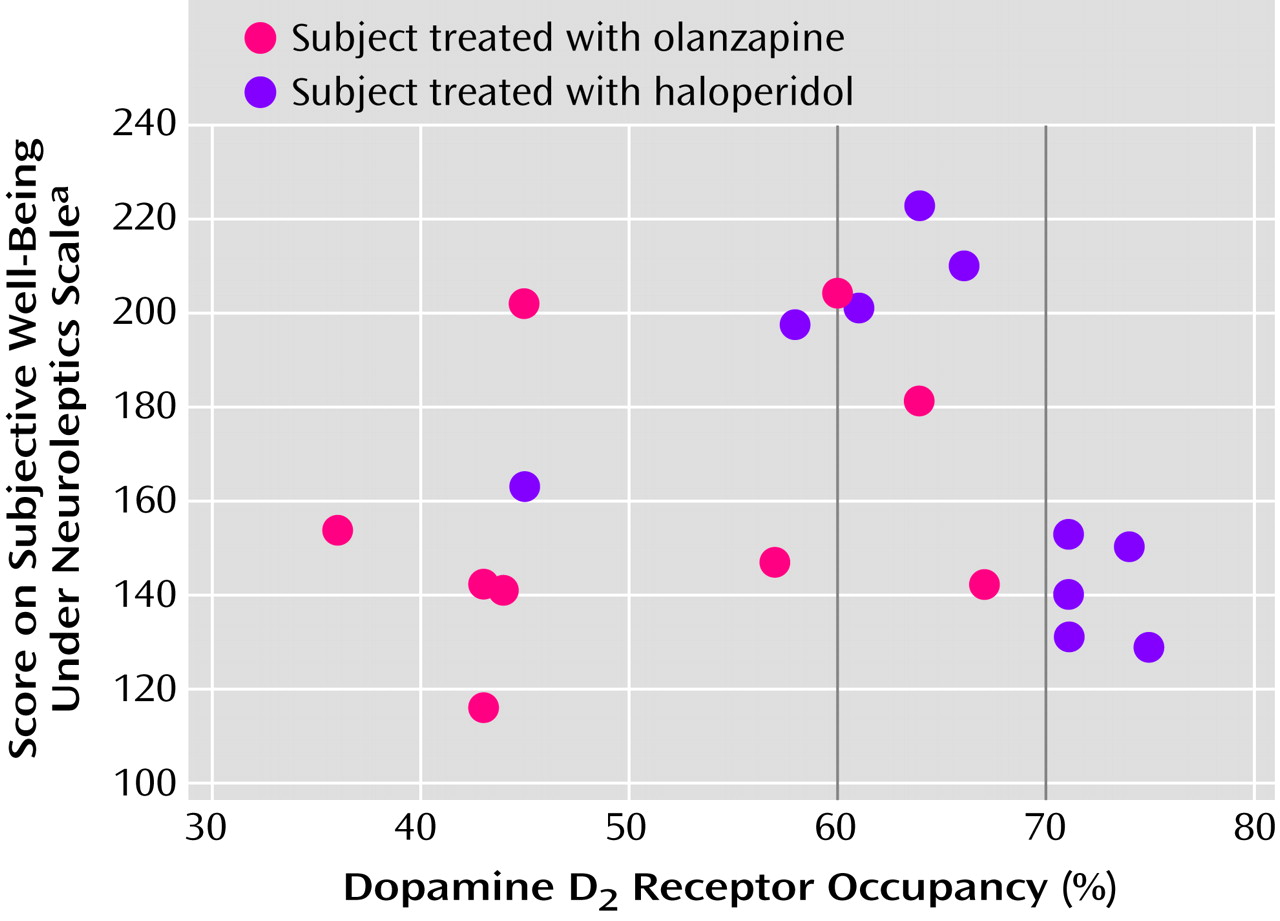

As seen in

Table 3 and

Figure 1, patients with D

2 receptor occupancy levels between 60% and 70% (N=6) had a significantly higher total score on the Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptics Scale than did subjects with D

2 receptor occupancy levels higher than 70% (N=5). In addition, the total score on the Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptics Scale for subjects with D

2 receptor occupancy levels between 60% and 70% was significantly higher when compared with that of subjects with D

2 receptor occupancy levels either lower than 60% or higher than 70% (N=13; mean=151.2, SD=24.7) (t=3.3, df=17, p=0.004). The mean scores on all the subscales of the Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptics Scale were significantly higher in subjects with D

2 receptor occupancy levels between 60% to 70% than in those with D

2 receptor occupancy levels higher than 70% (

Table 3).

Subjects treated with haloperidol accounted for most of the difference in scores on the Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptics Scale between participants with D2 receptor occupancy levels of 60%–70% (mean=211.3, SD=11.1, N=3) and those with D2 receptor occupancy levels of 71% or higher (mean=140.6, SD=10.8, N=5) (t=8.9, df=6, p<0.001).

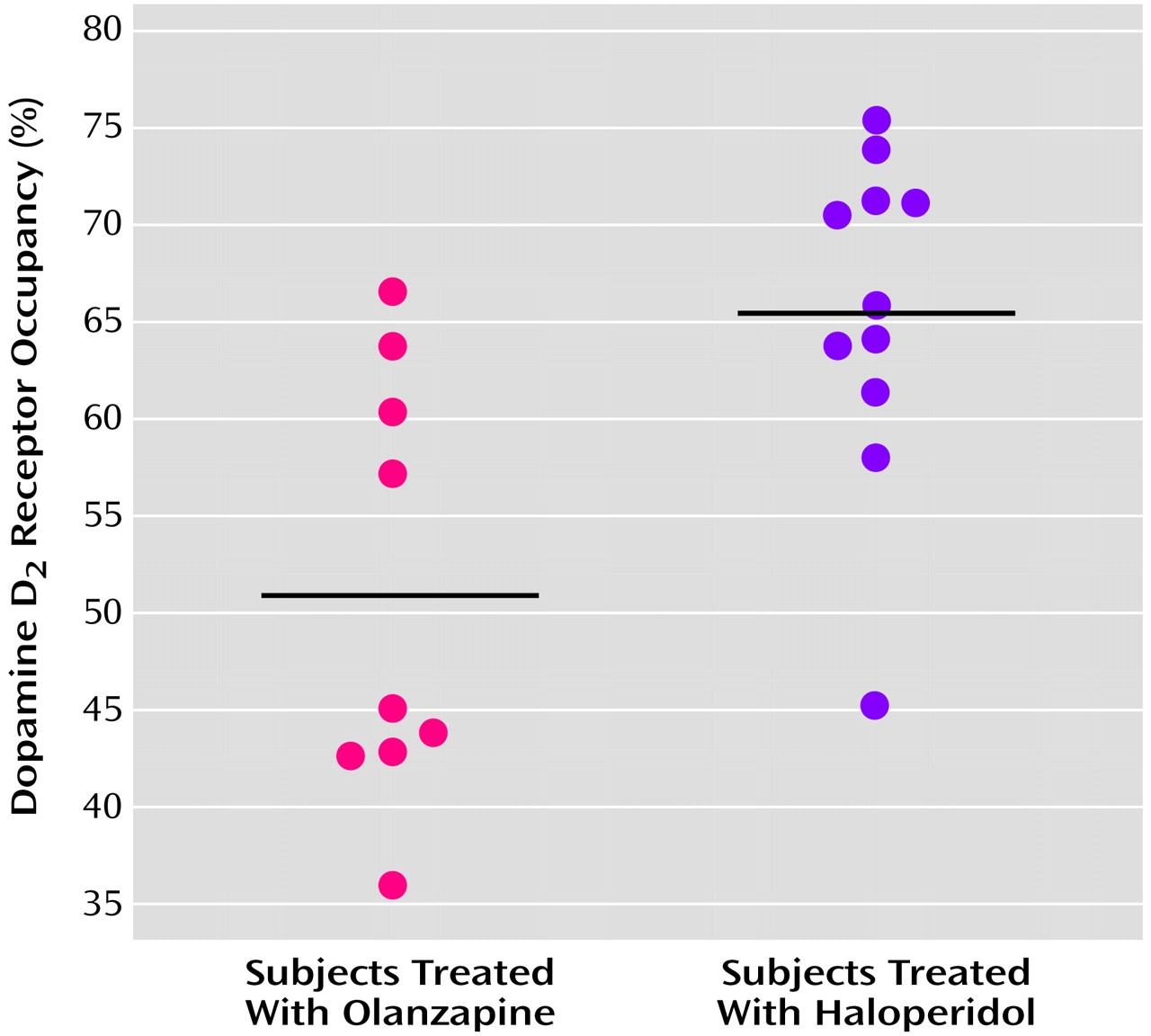

The mean D

2 receptor occupancy level in patients treated with olanzapine, 7.5 mg/day, was 51.0% (SD=11.1%, range=36%–67%). This was significantly lower than the mean D

2 receptor occupancy level of 65.5% (SD=8.7%, range=45%–75%) seen in patients treated with haloperidol, 2.5 mg/day (t=3.3, df=18, p=0.004) (

Figure 2).

D2 receptor occupancy level was not related to any baseline variable (age, weight, nicotine use, coffee use, or severity of illness).

Psychopathology and Extrapyramidal Side Effects

Significant improvement in CGI scores was seen in the patients treated with olanzapine (mean change at endpoint=–1.3 [SD=1.0]; t=3.42, df=7, p<0.05) and in the patients treated with haloperidol (mean change at endpoint=–0.8 [SD=0.9]; t=?, df=10, p<0.05). For the patients treated with olanzapine and those treated with haloperidol, nonsignificant improvement was seen for total scores on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (mean change at endpoint=–7.2 [SD=31.9] and –11.4 [SD=19.5], respectively) and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (mean change at endpoint=–2.8 [SD=12.1] and –1.2 [SD=3.6]). No significant differences in mean baseline (data not shown) and change at endpoint scores were found between participants treated with haloperidol and olanzapine.

We found no relationship between level of D2 receptor occupancy and response defined as difference in Clinical Global Impression, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, and Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores between baseline and endpoint.

No relationship was found at endpoint between D2 receptor occupancy level and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total or subscale scores or Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores.

At baseline, participants treated with haloperidol experienced more akathisia (mean=0.6, SD=0.8) than participants treated with olanzapine (mean=0.0, SD=0.0) (t=2.35, df=18, p<0.05) as measured with the Barnes Akathisia Scale. Change at endpoint did not differ significantly between groups. Within the haloperidol group, mean score on the Simpson-Angus Scale improved significantly (mean change at endpoint=–3.9, SD=5.0) (t=2.47, df=9, p<0.05).

At endpoint, akathisia and parkinsonism were generally absent. No relationship between the D2 receptor occupancy percentage and Barnes Akathisia Scale scores or Simpson-Angus Scale scores was found at endpoint.

Discussion

The results of this study offer evidence that D2 receptor occupancy between 60% and 70% is optimal for subjective experience of patients with recent-onset schizophrenia. Exceeding a level of 70% D2 receptor occupancy may substantially increase the risk of inducing worse subjective experience and noncompliance and therefore psychotic relapse.

The very low incidence and severity of extrapyramidal side effects we found is in line with the D

2 receptor occupancy threshold of 78% for development of extrapyramidal side effects. We were not able to replicate the relationship between D

2 receptor occupancy and response as found by Kapur et al.

(10). None of our patients had D

2 receptor occupancy levels that exceeded 75%, whereas five of the 10 patients with CGI scores that were much or very much improved in the study of Kapur et al. had D

2 receptor occupancy levels that exceeded 75%. This leaves clinicians with an almost insurmountable problem: the level of D

2 receptor occupancy needed for response in some patients exceeds the level above which the risk of negative influence on subjective experience is probably high. However, since the duration of treatment in the study by Kapur et al.

(10) was only 2 weeks, a D

2 receptor occupancy level lower than 75% for a longer period of time may result in response in most patients. Moreover, most of our patients had been treated with antipsychotic medication before study entry, thereby increasing the risk of a higher percentage of patients with treatment resistance than in a neuroleptic-naive population. This may also explain why we could not replicate the relationship between D

2 receptor occupancy and response.

We found a lower mean D

2 receptor occupancy (65.5%) in patients treated with haloperidol, 2.5 mg/day, than did Kapur et al.

(10), whose nine first-episode patients also received haloperidol, 2.5 mg/day (mean D

2 receptor occupancy=75%). This difference could reflect the need for treatment with very low doses for neuroleptic-naive patients compared with patients who have been treated with antipsychotic medication before. As far as we know, it is not clear when the need for higher doses emerges during treatment with antipsychotic medication.

The substantial interindividual variation in D

2 receptor occupancy at fixed amounts of low-dose haloperidol and olanzapine in this homogeneous group of subjects was in concordance with the wide interindividual variation at a given dose of haloperidol found in other studies

(7,

10).

Mean D

2 receptor occupancy in patients treated with olanzapine, 7.5 mg/day, was significantly lower than mean D

2 occupancy reached during treatment with haloperidol, 2.5 mg/day. The mean D

2 occupancy found with olanzapine, 7.5 mg/day, is in line with the saturation hyperbola as earlier described

(23). In a study on the D

2 receptor occupancy of olanzapine, more interindividual variation seemed to occur in patients receiving 5 mg/day of olanzapine than in patients receiving doses of 10 mg/day or higher

(23). In our study, more than half of the patients treated with olanzapine, 7.5 mg/day, reached D

2 receptor occupancy of 45% or less; however, one-third of these patients showed an occupancy of 60% or more.

Olanzapine, 7.5 mg/day, did not show superior subjective response compared with haloperidol, 2.5 mg/day, in patients with recent-onset schizophrenia. In fact, subjective experience improved significantly only during treatment with haloperidol. This is an unexpected finding given the advantages in subjective experience found during treatment with olanzapine in former studies. Inordinately high levels of D2 receptor occupancy in the typical comparison group have confounded these studies. However, our study may be biased by the relatively low D2 receptor occupancy associated with the treatment of olanzapine, 7.5 mg/day. We therefore cannot rule out the possibility that olanzapine in a dose that gives rise to D2 receptor occupancy beyond 70% may still result in superior subjective well-being. The decline in subjective well-being with an occupancy of striatal D2 receptors above 70% may be an issue only relevant for haloperidol. However, future studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

Fast dissociation from the D

2 receptor could make an antipsychotic medication more accommodating of physiological dopamine transmission, permitting antipsychotic effect without major side effects

(25). This proposed mechanism could also account for superior subjective experience associated with atypical antipsychotic drugs. Since we found no evidence for superior subjective experience associated with low-dose olanzapine compared with low-dose haloperidol, we suppose that besides faster dissociation, the level of D

2 occupancy is also important for the influence of antipsychotic drugs on subjective experience. Moreover, subjective experience is probably influenced not only by effects on modulation of the D

2 neurotransmission but effects on receptors other than D

2 may also account for worse subjective experience. Probably an ideal antipsychotic medication binds selectively to the D

2 receptor and dissociates relatively fast from it, without causing enduring occupancy beyond about 70%.

Our study has several limitations. First, mesolimbic D

2 receptors might be more relevant to subjective experience than striatal D

2 receptors. Since there are no indications for differences in striatal and extrastriatal D

2 occupancy in patients treated with haloperidol, we think that striatal occupancy is a reasonable surrogate of mesolimbic D

2 occupancy, at least in the case of haloperidol

(31,

32). Second, most of the patients included used antipsychotic medication before study entry, probably altering their D

2 binding capacity. We think that the study duration of 6 weeks makes confounding effects on subjective experience measures caused by former medication less probable. Third, one-half of the patients used oxazepam as adjunctive medication. However, occupancy in a PET study of lorazepam has been shown to have no influence on striatal [

11C]raclopride binding

(33). Fourth, the 7.5 mg/day dose of olanzapine was too low for most (not all) patients with recent-onset schizophrenia previously treated with antipsychotic medication. Comparison of haloperidol, 2.5 mg/day, with olanzapine, 10 mg/day, might give ideal D

2 occupancy matching. Future comparison of subjective experience of typical and atypical antipsychotic medication in doses that lead to the same range of D

2 receptor occupancy is needed. Fifth, only one out of 24 subjects was female. Finally, in the present study plasma levels of study medication were not measured. However, compliance with study medication was guaranteed, since nursing staff supervised intake of medication.

In summary, we found evidence that a level of D2 receptor occupancy between 60% and 70% is optimal for subjective experience of patients with recent-onset schizophrenia. We found substantial interindividual variation in D2 receptor occupancy at fixed amounts of low-dose haloperidol and olanzapine. Olanzapine, 7.5 mg/day, showed no superior subjective response over haloperidol, 2.5 mg/day. From the perspective of subjective experience of patients, haloperidol needs to be individually titrated in the very low dose range (probably 1.5–3 mg/day) to reach optimal occupancy, and olanzapine needs to be dosed higher than 7.5 mg/day for most patients with recent-onset schizophrenia previously treated with antipsychotic medication.